Puberty & Cognition

Adolescence is a period that begins with puberty and ends with the transition to adulthood (lasting approximately from ages 10–18). Physical changes associated with puberty are triggered by hormones. Changes happen at different rates in distinct parts of the brain and increase adolescents’ propensity for risky behavior. Cognitive changes include improvements in complex and abstract thought. Adolescents’ relationships with parents go through a period of redefinition in which adolescents become more autonomous. Peer relationships are important sources of support, but companionship during adolescence can also promote problem behaviors. Identity formation occurs as adolescents explore and commit to different roles and ideological positions. Because so much is happening in these years, psychologists have focused a great deal of attention on the period of adolescence.

Physical Development in Adolescence

Learning Objectives: Physical Development in Adolescence

- Identify physical transformations in adolescence.

- Describe the effects associated with early and late onset of puberty, and how they differ for boys and girls.

- Identify three major brain developments in adolescence.

- Explain the asynchrony in two of the brain developments and how it is responsible for certain adolescent behaviors.

- Explain why sleep is important for adolescents.

Puberty is a period of rapid growth and sexual maturation. These changes begin sometime between age eight and fourteen. Girls begin puberty at around ten years of age and boys begin approximately two years later. Pubertal changes take around three to four years to complete. Adolescents experience an overall physical growth spurt. The growth proceeds from the extremities toward the torso. This is referred to as distal–proximal development. First the hands grow, then the arms, and finally the torso. The overall physical growth spurt results in 10-11 inches of added height and 50 to 75 pounds of increased weight. The head begins to grow sometime after the feet have gone through their period of growth. Growth of the head is preceded by growth of the ears, nose, and lips. The difference in these patterns of growth result in adolescents appearing awkward and out-of-proportion. As the torso grows, so do the internal organs. The heart and lungs experience dramatic growth during this period.

During childhood, boys and girls are quite similar in height and weight. However, gender differences become apparent during adolescence. From approximately age ten to fourteen, the average girl is taller, but not heavier, than the average boy. After that, the average boy becomes both taller and heavier, although individual differences are certainly apparent. As adolescents physically mature, weight differences are more noteworthy than height differences. At eighteen years of age, those that are heaviest weigh almost twice as much as the lightest, but the tallest teens are only about 10% taller than the shortest (Seifert, 2012).

Both height and weight can certainly be sensitive issues for some teenagers. Most modern societies, and the teenagers in them, tend to favor relatively short women and tall men, as well as a somewhat thin body build, especially for girls and women. Yet, neither socially preferred height nor thinness is the destiny for most individuals. Being overweight, in particular, has become a common, serious problem in modern society due to the prevalence of diets high in fat and lifestyles low in activity (Tartamella, Herscher, & Woolston, 2004). The educational system has, unfortunately, contributed to the problem as well by gradually restricting the number of physical education classes in the past two decades.

Average height and weight are also related somewhat to racial and ethnic background. In general, children of Asian background tend to be slightly shorter than children of European and North American background. The latter in turn tend to be shorter than children from African societies (Eveleth & Tanner, 1990). Body shape differs slightly as well, though the differences are not always visible until after puberty. Asian background youth tend to have arms and legs that are a bit short relative to their torsos, and African background youth tend to have relatively long arms and legs. The differences are only averages, as there are large individual differences as well.

Sexual Development

Typically, this spurt in physical growth is followed by the development of sexual maturity. Sexual changes are divided into two categories: Primary sexual characteristics and secondary sexual characteristics. Primary sexual characteristics are changes in the reproductive organs. For females, primary characteristics include growth of the uterus and menarche or the first menstrual period. The female gametes, which are stored in the ovaries, are present at birth, but are immature. Each ovary contains about 400,000 gametes, but only 500 will become mature eggs (Crooks & Baur, 2007). Beginning at puberty, one ovum ripens and is released about every 28 days during the menstrual cycle. Stress and higher percentage of body fat can bring menstruation at younger ages. For males, this includes growth of the testes, penis, scrotum, and spermarche or first ejaculation of semen. This occurs between 11 and 15 years of age.

Secondary sexual characteristics are visible physical changes that signal sexual maturity but are not directly linked to reproduction. For females, breast development occurs around age 10, although full development takes several years. Hips broaden, and pubic and underarm hair develops and also becomes darker and coarser. For males this includes broader shoulders and a lower voice as the larynx grows. Hair becomes coarser and darker, and hair growth occurs in the pubic area, under the arms and on the face.

Effects of Pubertal Age. The age of puberty is getting younger for children throughout the world. According to Euling et al. (2008) data are sufficient to suggest a trend toward an earlier breast development onset and menarche in girls. A century ago the average age of a girl’s first period in the United States and Europe was 16, while today it is around 13. Because there is no clear marker of puberty for boys, it is harder to determine if boys are also maturing earlier. In addition to better nutrition, less positive reasons associated with early puberty for girls include increased stress, obesity, and endocrine disrupting chemicals.

Cultural differences are noted with African American girls enter puberty the earliest. Hispanic girls start puberty the second earliest, while European-American girls rank third in their age of starting puberty, and Asian-American girls, on average, develop last. Although African-American girls are typically the first to develop, they are less likely to experience negative consequences of early puberty when compared to European-American girls (Weir, 2016).

Research has demonstrated mental health problems linked to children who begin puberty earlier than their peers. For girls, early puberty is associated with depression, substance use, eating disorders, disruptive behavior disorders, and early sexual behavior (Graber, 2013). Early maturing girls demonstrate more anxiety and less confidence in their relationships with family and friends, and they compare themselves more negatively to their peers (Weir, 2016).

Problems with early puberty seem to be due to the mismatch between the child’s appearance and the way she acts and thinks. Adults especially may assume the child is more capable than she actually is, and parents might grant more freedom than the child’s age would indicate. For girls, the emphasis on physical attractiveness and sexuality is emphasized at puberty and they may lack effective coping strategies to deal with the attention they receive, especially from older boys.

Additionally, mental health problems are more likely to occur when the child is among the first in his or her peer group to develop. Because the preadolescent time is one of not wanting to appear different, early developing children stand out among their peer group and gravitate toward those who are older. For girls, this results in them interacting with older peers who engage in risky behaviors such as substance use and early sexual behavior (Weir, 2016).

Boys also see changes in their emotional functioning at puberty. According to Mendle, Harden, Brooks-Gunn, and Graber (2010), while most boys experienced a decrease in depressive symptoms during puberty, boys who began puberty earlier and exhibited a rapid tempo, or a fast rate of change, actually increased in depressive symptoms. The effects of pubertal tempo were stronger than those of pubertal timing, suggesting that rapid pubertal change in boys may be a more important risk factor than the timing of development. In a further study to better analyze the reasons for this change, Mendle, Harden, Brooks-Gunn and Graber (2012) found that both early maturing boys and rapidly maturing boys displayed decrements in the quality of their peer relationships as they moved into early adolescence, whereas boys with more typical timing and tempo development actually experienced improvements in peer relationships. The researchers concluded that the transition in peer relationships may be especially challenging for boys whose pubertal maturation differs significantly from those of others their age. Consequences for boys attaining early puberty were increased odds of cigarette, alcohol, or another drug use (Dudovitz, et al., 2015). However, from the outside, early maturing boys are also often perceived as well-adjusted, popular, and tend to hold leadership positions.

The Adolescent Brain

The brain undergoes dramatic changes during adolescence. Although it does not get larger, it matures by becoming more interconnected and specialized (Giedd, 2015). The myelination and development of connections between neurons continues. This results in an increase in the white matter of the brain that allows the adolescent to make significant improvements in their thinking and processing skills. Different brain areas become myelinated at different times. For example, the brain’s language areas undergo myelination during the first 13 years. Completed insulation of the axons consolidates these language skills but makes it more difficult to learn a second language. With greater myelination, however, comes diminished plasticity as a myelin coating inhibits the growth of new connections (Dobbs, 2012).

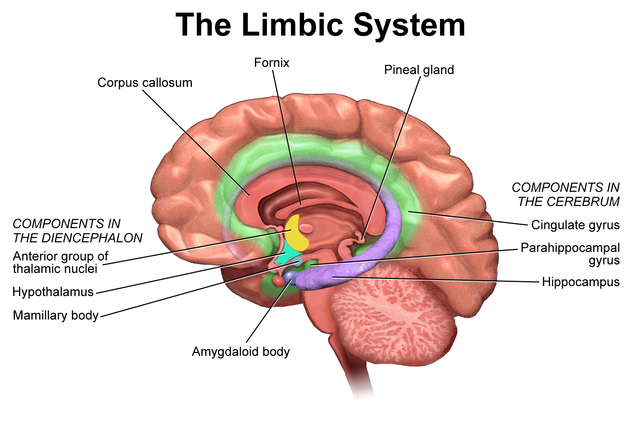

Even as the connections between neurons are strengthened, synaptic pruning occurs more than during childhood as the brain adapts to changes in the environment. This synaptic pruning causes the gray matter of the brain, or the cortex, to become thinner but more efficient (Dobbs, 2012). The corpus callosum, which connects the two hemispheres, continues to thicken allowing for stronger connections between brain areas. Additionally, the hippocampus becomes more strongly connected to the frontal lobes, allowing for greater integration of memory and experiences into our decision making.

The limbic system, which regulates emotion and reward, is linked to the hormonal changes that occur at puberty. The limbic system is also related to novelty seeking and a shift toward interacting with peers. In contrast, the prefrontal cortex which is involved in the control of impulses, organization, planning, and making good decisions, does not fully develop until the mid-20s. According to Giedd (2015), an important outcome of the early development of the limbic system combined with the later development of the prefrontal cortex is the “mismatch” in timing between the two. The approximately ten years that separate the development of these two brain areas can result in increases in risky behavior, poor decision making, and weak emotional control for the adolescent. When puberty begins earlier, this mismatch lasts even longer.

Teens typically take more risks than adults and according to research it is because they weigh risks and rewards differently than adults do (Dobbs, 2012). The brain’s sensitivity to the neurotransmitter dopamine peaks during adolescence, and dopamine is involved in reward circuits, so adolescents may judge that the possible rewards outweigh the risks. Adolescents respond especially strongly to social rewards during activities, and they prefer the company of others their same age. Chein et al. (2011) found that peers sensitize brain regions associated with potential rewards. For example, adolescent drivers make more risky driving decisions when with friends to impress them, and teens are much more likely to commit crimes together in comparison to adults (30 and older) who commit them alone (Steinberg et al., 2017). In addition to dopamine, the adolescent brain is affected by oxytocin which facilitates bonding and makes social connections more rewarding. With both dopamine and oxytocin engaged, it is no wonder that adolescents seek peers and excitement in their lives that could actually end up endangering them.

Because of all the changes that occur in the brain during adolescence, the chances for abnormal development, including the emergence of mental illness, also rise. In fact, 50% of all mental illnesses occur by the age 14 and 75% occur by age 24 (Giedd, 2015). Additionally, during this period of development the adolescent brain is especially vulnerable to damage from drug exposure. For example, repeated exposure to marijuana can affect cellular activity in the endocannabinoid system. Consequently, adolescents are more sensitive to the effects of repeated marijuana exposure (Weir, 2015).

However, researchers have also focused on the highly adaptive qualities of the adolescent brain which allow the adolescent to move away from the family towards the outside world (Dobbs, 2012; Giedd, 2015). Novelty seeking and risk taking can generate positive outcomes including meeting new people and seeking out new situations. Separating from the family and moving into new relationships and different experiences are actually quite adaptive– for adolescents and for society.

Social cognitive development during adolescence.

Suparna Choudhury, Sarah-Jayne Blakemore, Tony Charman Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, Volume 1, Issue 3, December 2006, Pages 165–174, https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsl024

Adolescent Sleep

According to the National Sleep Foundation (NSF; 2016), to function their best, adolescents need about 8 to 10 hours of sleep each night. The most recent Sleep in America poll in 2006 indicated that adolescents between sixth and twelfth grade were not getting the recommended amount of sleep. On average, adolescents slept only 7 ½ hours per night on school nights with younger adolescents getting more than older ones (8.4 hours for sixth graders and only 6.9 hours for those in twelfth grade). For the older adolescents, only about one in ten (9%) get an optimal amount of sleep, and those who don’t are more likely to experience negative consequences the following day. These include depressed mood, feeling tired or sleepy, being cranky or irritable, falling asleep in school, and drinking caffeinated beverages (NSF, 2016). Additionally, sleep deprived adolescents are at greater risk for substance abuse, car crashes, poor academic performance, obesity, and a weakened immune system (Weintraub, 2016).

Troxel et al. (2019) found that insufficient sleep in adolescents is also a predictor of risky sexual behaviors. Reasons given for this include that those adolescents who stay out late, typically without parental supervision, are more likely to engage in a variety of risky behaviors, including risky sex, such as not using birth control or using substances before/during sex. An alternative explanation for risky sexual behavior is that the lack of sleep increases impulsivity while negatively affecting decision-making processes.

Why don’t adolescents get adequate sleep? In addition to known environmental and social factors, including work, homework, media, technology, and socializing, the adolescent brain is also a factor. As adolescent go through puberty, their circadian rhythms change and push back their sleep time until later in the evening (Weintraub, 2016). This biological change not only keeps adolescents awake at night, it makes it difficult for them to wake up. When they are awakened too early, their brains do not function optimally. Impairments are noted in attention, academic achievement, and behavior while increases in tardiness and absenteeism are also seen.

To support adolescents’ later circadian rhythms, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that school begin no earlier than 8:30 a.m. Unfortunately, over 80% of American schools begin their day earlier than 8:30 a.m. with an average start time of 8:03 a.m. (Weintraub, 2016). Psychologists and other professionals have been advocating for later start times, based on research demonstrating better student outcomes for later start times. More middle and high schools have changed their start times to better reflect the sleep research. However, the logistics of changing start times and bus schedules are proving too difficult for some schools, leaving many adolescent vulnerable to the negative consequences of sleep deprivation. Troxel et al. (2019) cautions that adolescents should find a middle ground between sleeping too little during the school week and too much during the weekends. Keeping consistent sleep schedules of too little sleep will result in sleep deprivation but oversleeping on weekends can affect the natural biological sleep cycle making it harder to sleep on weekdays

Cognitive Development in Adolescence

Learning Objectives: Cognitive Development in Adolescence

- Describe Piaget’s formal operational stage and the characteristics of formal operational thought.

- Identify the advances and limitations of formal operational thought.

- Describe metacognition.

- Describe adolescent egocentrism.

- Describe the limitations of adolescent thinking.

- Explain the reason school transitions are difficult for adolescents.

- Describe the developmental mismatch between adolescent needs and school contexts.

Adolescence is a time of rapid cognitive development. Biological changes in brain structure and connectivity in the brain interact with increased experience, knowledge, and changing social demands to produce rapid cognitive growth. These changes generally begin at puberty or shortly thereafter, and some skills continue to develop as an adolescent ages. Development of executive functions, or cognitive skills that enable the control and coordination of thoughts and behavior, are generally associated with the prefrontal cortex area of the brain. The thoughts, ideas, and concepts developed at this period of life greatly influence one’s future life and play a major role in character and personality formation.

Improvements in basic thinking abilities generally occur in several areas during adolescence:

- Attention. Improvements are seen in selective attention (the process by which one focuses on one stimulus while tuning out another), as well as divided attention (the ability to pay attention to two or more stimuli at the same time).

- Memory. Improvements are seen in working memory and long-term memory.

- Processing speed. Adolescents think more quickly than children. Processing speed improves sharply between age five and middle adolescence, levels off around age 15, and then remains largely the same between late adolescence and adulthood.

Formal Operational Thought

In the last of the Piagetian stages, the young adolescent becomes able to reason not only about tangible objects and events, but also about hypothetical or abstract ones. Hence, it has the name formal operational stage—the period when the individual can “operate” on “forms” or representations. This allows an individual to think and reason with a wider perspective. This stage of cognitive development, which Piaget called formal operational thought, marks a movement from an ability to think and reason from concrete visible events to an ability to think hypothetically and entertain what-if possibilities about the world. An individual can solve problems through abstract concepts and utilize hypothetical and deductive reasoning. Adolescents initially use trial and error to solve problems, but the ability to systematically solve a problem in a logical and methodical way emerges.

Hypothetical and Abstract Thinking

One of the major advances of formal operational thought is the capacity to think of possibility, not just reality. Adolescents’ thinking is less bound to concrete events than that of children; they can contemplate possibilities outside the realm of what currently exists. One manifestation of the adolescent’s increased facility with thinking about possibilities is the improvement of skill in deductive reasoning (also called top-down reasoning), which leads to the development of hypothetical thinking. This provides the ability to plan ahead, see the future consequences of an action and to provide alternative explanations of events. It also makes adolescents more skilled debaters, as they can reason against a friend’s or parent’s position. Adolescents also develop a more sophisticated understanding of probability.

Formal Operational Thinking in the Classroom

School is a main contributor in guiding students towards formal operational thought. With students at this level, the teacher can pose hypothetical (or contrary-to-fact) problems: “What if the world had never discovered oil?” or “What ifthe first European explorers had settled first in California instead of on the East Coast of the United States?” To answer such questions, students must use hypothetical reasoning, meaning that they must manipulate ideas that vary in several ways at once, and do so entirely in their minds.

The hypothetical reasoning that concerned Piaget primarily involved scientific problems. His studies of formal operational thinking therefore often look like problems that middle or high school teachers pose in science classes. In one problem, for example, a young person is presented with a simple pendulum, onto which different amounts of weight can be hung (Inhelder & Piaget, 1958). The experimenter asks: “What determines how fast the pendulum swings: the length of the string holding it, the weight attached to it, or the distance that it is pulled to the side?” The young person is not allowed to solve this problem by trial-and-error with the materials themselves, but must reason a way to the solution mentally. To do so systematically, he or she must imagine varying each factor separately, while also imagining the other factors that are held constant. This kind of thinking requires facility at manipulating mental representations of the relevant objects and actions—precisely the skill that defines formal operations.

As you might suspect, students with an ability to think hypothetically have an advantage in many kinds of school work: by definition, they require relatively few “props” to solve problems. In this sense they can in principle be more self-directed than students who rely only on concrete operations—certainly a desirable quality in the opinion of most teachers. Note, though, that formal operational thinking is desirable but not sufficient for school success, and that it is far from being the only way that students achieve educational success. Formal thinking skills do not ensure that a student is motivated or well-behaved, for example, nor does it guarantee other desirable skills. The fourth stage in Piaget’s theory is really about a particular kind of formal thinking, the kind needed to solve scientific problems and devise scientific experiments. Since many people do not normally deal with such problems in the normal course of their lives, it should be no surprise that research finds that many people never achieve or use formal thinking fully or consistently, or that they use it only in selected areas with which they are very familiar (Case & Okomato, 1996). For teachers, the limitations of Piaget’s ideas suggest a need for additional theories about cognitive developments—ones that focus more directly on the social and interpersonal issues of childhood and adolescence.

- Propositional thought. The appearance of more systematic, abstract thinking also allows adolescents to comprehend higher order abstract ideas, such as those inherent in puns, proverbs, metaphors, and analogies. Their increased facility permits them to appreciate the ways in which language can be used to convey multiple messages, such as satire, metaphor, and sarcasm. (Children younger than age nine often cannot comprehend sarcasm at all). This also permits the application of advanced reasoning and logical processes to social and ideological matters such as interpersonal relationships, politics, philosophy, religion, morality, friendship, faith, fairness, and honesty. This newfound ability also allows adolescents to take other’s perspectives in more complex ways, and to be able to better think through others’ points of view.

- Metacognition. Meta-cognition refers to “thinking about thinking.” This often involves monitoring one’s own cognitive activity during the thinking process. Adolescents are more aware of their own thought processes and can use mnemonic devices and other strategies to think and remember information more efficiently. Metacognition provides the ability to plan ahead, consider the future consequences of an action, and provide alternative explanations of events.

- Relativism. The capacity to consider multiple possibilities and perspectives often leads adolescents to the conclusion that nothing is absolute– everything appears to be relative. As a result, teens often start questioning everything that they had previously accepted– such as parent and family values, authority figures, religious practices, school rules, and political events. They may even start questioning things that took place when they were younger, like adoption or parental divorce. It is common for parents to feel that adolescents are just being argumentative, but this behavior signals a normal phase of cognitive development.

Adolescent Egocentrism

Adolescents’ newfound meta-cognitive abilities also have an impact on their social cognition, as it results in increased introspection, self-consciousness, and intellectualization. Adolescents are much better able to understand that people do not have complete control over their mental activity. Being able to introspect may lead to forms of egocentrism, or self-focus, in adolescence. Adolescent egocentrism is a term that David Elkind used to describe the phenomenon of adolescents’ inability to distinguish between their perception of what others think about them and what people actually think in reality. Elkind’s theory on adolescent egocentrism is drawn from Piaget’s theory on cognitive developmental stages, which argues that formal operations enable adolescents to construct imaginary situations and abstract thinking.

Accordingly, adolescents are able to conceptualize their own thoughts and conceive of other people’s thoughts. However, Elkind pointed out that adolescents tend to focus mostly on their own perceptions, especially on their behaviors and appearance, because of the “physiological metamorphosis” they experience during this period. This leads to adolescents’ belief that other people are as attentive to their behaviors and appearance as they are themselves (Elkind, 1967; Schwartz, P. D., Maynard, A. M., & Uzelac, S. M., 2008). According to Elkind, adolescent egocentrism results in two distinct problems in thinking: the imaginary audience and the personal fable. These likely peak at age fifteen, along with self-consciousness in general.

Imaginary audience is a term that Elkind used to describe the phenomenon that an adolescent anticipates the reactions of other people to him/herself in actual or impending social situations. Elkind argued that this kind of anticipation could be explained by the adolescent’s conviction that others are as admiring or as critical of them as they are of themselves. As a result, an audience is created, as the adolescent believes that he or she will be the focus of attention. However, more often than not the audience is imaginary because in actual social situations individuals are not usually the sole focus of public attention. Elkind believed that the construction of imaginary audiences would partially account for a wide variety of typical adolescent behaviors and experiences; and imaginary audiences played a role in the self-consciousness that emerges in early adolescence. However, since the audience is usually the adolescent’s own construction, it is privy to his or her own knowledge of him/herself. According to Elkind, the notion of imaginary audience helps to explain why adolescents usually seek privacy and feel reluctant to reveal themselves–it is a reaction to the feeling that one is always on stage and constantly under the critical scrutiny of others.

Elkind also suggested that adolescents have another complex set of beliefs: They are convinced that their own feelings are unique and they are special and immortal. Personal fable is the term Elkind used to describe this notion, which is the complement of the construction of an imaginary audience. Since an adolescent usually fails to differentiate their own perceptions and those of others, they tend to believe that they are of importance to so many people (the imaginary audiences) that they come to regard their feelings as something special and unique. They may feel that they are the only ones who have experienced strong and diverse emotions, and therefore others could never understand how they feel. This uniqueness in one’s emotional experiences reinforces the adolescent’s belief of invincibility, especially to death.

This adolescent belief in personal uniqueness and invincibility becomes an illusion that they can be above some of the rules, constraints, and laws that apply to other people; even consequences such as death (called the invincibility fable). This belief that one is invincible removes any impulse to control one’s behavior (Lin, 2016). Therefore, adolescents will engage in risky behaviors, such as drinking and driving or unprotected sex, and feel they will not suffer any negative consequences.

Intuitive and Analytic Thinking

Piaget emphasized the sequence of cognitive developments that unfold in four stages. Others suggest that thinking does not develop in sequence, but instead, that advanced logic in adolescence may be influenced by intuition. Cognitive psychologists often refer to intuitive and analytic thought as the dual-process model; the notion that humans have two distinct networks for processing information (Kuhn, 2013.)

Intuitive thought is automatic, unconscious, and fast, and it is more experiential and emotional. In contrast, analytic thought is deliberate, conscious, and rational (logical). Although these systems interact, they are distinguishable (Kuhn, 2013). Intuitive thought is easier, quicker, and more commonly used in everyday life. The discrepancy between the maturation of the limbic system and the prefrontal cortex, as discussed in the section on adolescent brain development earlier in this module, may make teens more prone to emotional intuitive thinking than adults.

As adolescents develop, they gain in logic/analytic thinking ability but may sometimes regress, with social context, education, and experiences becoming major influences. Simply put, being “smarter” as measured by an intelligence test does not advance or anchor cognition as much as having more experience, in school and in life (Klaczynski & Felmban, 2014).

Risk-taking

Because most injuries sustained by adolescents are related to risky behavior (alcohol consumption and drug use, reckless or distracted driving, and unprotected sex), a great deal of research has been conducted to examine the cognitive and emotional processes underlying adolescent risk-taking. In addressing this issue, it is important to distinguish three facets of these questions: (1) whether adolescents are more likely to engage in risky behaviors (prevalence), (2) whether they make risk-related decisions similarly or differently than adults (cognitive processing perspective), or (3) whether they use the same processes but weigh facets differently and thus arrive at different conclusions. Behavioral decision-making theory proposes that adolescents and adults both weigh the potential rewards and consequences of an action. However, research has shown that adolescents seem to give more weight to rewards, particularly social rewards, than do adults. Adolescents value social warmth and friendship, and their hormones and brains are more attuned to those values than to a consideration of long-term consequences (Crone & Dahl, 2012).

Some have argued that there may be evolutionary benefits to an increased propensity for risk-taking in adolescence. For example, without a willingness to take risks, teenagers would not have the motivation or confidence necessary to leave their family of origin. In addition, from a population perspective, is an advantage to having a group of individuals willing to take more risks and try new methods, counterbalancing the more conservative elements typical of the received knowledge held by older adults.

Education in Adolescence

Adolescents spend more waking time in school than in any other context (Eccles & Roeser, 2011). Secondary education denotes the school years after elementary school (known as primary education) and before college or university (known as tertiary education). Adolescents who complete primary education (learning to read and write) and continue on through secondary and tertiary education tend to also have better health, wealth, and family life (Rieff, 1998). Because the average age of puberty has declined over the years, middle schools were created for grades 5 or 6 through 8 as a way to distinguish between early adolescence and late adolescence, especially because these adolescents differ biologically, cognitively and emotionally and definitely have different needs.

Transition to middle school is stressful and the transition is often complex. When students transition from elementary to middle school, many students are undergoing physical, intellectual, social, emotional, and moral changes as well (Parker, 2013). Research suggests that early adolescence is an especially sensitive developmental period (McGill et al., 2012). Some students mature faster than others. Students who are developmentally behind typically experience more stress than their counterparts (U.S. Department of Education, 2008). Consequently, they may earn lower grades and display decreased academic motivation, which may increase the rate of dropping out of school (U.S. Department of Education, 2008). For many middle school students, academic achievement slows down and behavioral problems can increase.

Regardless of a student’s gender or ethnicity, middle school can be challenging. Although young adolescents seem to desire independence, they also need protection, security, and structure (Brighton, 2007). Baly, Cornell, and Lovegrove (2014) found that bullying increases in middle school, particularly in the first year. Just when egocentrism is at its height, students are worried about being thrown into an environment of independence and responsibility. Additionally, unlike elementary school, concerns arise regarding structural changes– students typically go from having one primary teacher in elementary school to multiple different teachers during middle school. They are expected to get to and from classes on their own, manage time wisely, organize and keep up with materials for multiple classes, be responsible for all classwork and homework from multiple teachers, and at the same time develop and maintain a social life (Meece & Eccles, 2010). Students are trying to build new friendships and maintain ones they already have. As noted throughout this module, peer acceptance is particularly important. Another aspect to consider is technology. Typically, adolescents get their first cell phone at about age 11 and, simultaneously, they are also expected to research items on the Internet. Social media use and texting increase dramatically and the research finds both costs and benefits to this use (Coyne et al., 2018).

Stage-environment Fit. A useful perspective that explains much of the difficulty faced by early adolescents in middle school, and the declines found in classroom engagement and academic achievement, is stage-environment fit theory (Eccles, Midgley, Wigfield, Buchanan, Reuman, Flanagan, & MacIver, 1993). This theory highlights the developmental mismatch between the needs of adolescents and the characteristics of the middle school context. At the same time that teens are developing greater needs for cognitive challenges, autonomy, independence, and stronger relationships outside the family, schools are becoming more rigid, controlling, and unstimulating. The middle school environment is experienced as less supportive than elementary school, with multiple teachers and less closeness and warmth in teacher-student relationships. Disciplinary concerns can make classrooms more controlling, while standardized testing and organizational constraints make curriculum more uniform, and less challenging and interesting. Existing relationships with peers are often disrupted and students find themselves in a larger and more complex social context. This poor fit between the needs of students at certain stages and their school contexts is more pronounced over school transitions, but continues all throughout secondary education.

As adolescents enter into high school, their continued cognitive development allows them to think abstractly, analytically, hypothetically, and logically, which is all formal operational thought. High school emphasizes formal thinking in attempt to prepare graduates for college where analysis is required. Overall, high school graduation rates in the United States have increased steadily over the past decade, reaching 83.2 percent in 2016 after four years in high school (Gewertz, 2017). Additionally, many students in the United States do attend college. Unfortunately, though, about half of those who go to college leave without completing a degree (Kena et al., 2016). Those that do earn a degree, however, do make more money and have an easier time finding employment. The key here is understanding adolescent development and supporting teens in making decisions about college or alternatives to college after high school.

Academic achievement during adolescence is predicted by factors that are interpersonal (e.g., parental engagement in adolescents’ education), intrapersonal (e.g., intrinsic motivation), and institutional (e.g., school quality). Academic achievement is important in its own right as a marker of positive adjustment during adolescence but also because academic achievement sets the stage for future educational and occupational opportunities. The most serious consequence of school failure, particularly dropping out of school, is the high risk of unemployment or underemployment in adulthood that follows. High achievement can set the stage for college or future vocational training and opportunities.

References

Baly, M.W., Cornell, D.G., & Lovegrove, P. (2014). A longitudinal investigation of self and peer reports of bullying victimization across middle school. Psychology in the Schools, 51(3), 217-240.

Brighton, K. L. (2007). Coming of age: The education and development of young adolescents. Westerville, OH: National Middle School Association.

Case, R. and Okamoto, Y. 1996. The role of central conceptual structures in the development of children’s thought. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 61, (1–2, Serial No. 246).

Chein, J., Albert, D., O’Brien, L., Uckert, K., & Steinberg, L. (2011). Peers increase adolescent risk taking by enhancing activity in the brain’s reward circuitry. Developmental Science, 14(2), F1-F10.

Coyne, S.M., Padilla-Walker, L.M., & Holmgren, H.G. (2018). A six-year longitudinal study of texting trajectories duringadolescence. Child Development, 89(1), 58-65.

Crone, E.A., & Dahl, R.E. (2012). Understanding adolescence as a period of social-affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13(9), 636-650.

Crooks, K. L., & Baur, K. (2007). Our sexuality (10th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Dobbs, D. (2012). Beautiful brains. National Geographic, 220(4), 36.

Eccles, J. S., Midgley, C., Wigfield, A., Buchanan, C. M., Reuman, D., Flanagan, C., & MacIver, D. (1993). Development during adolescence: The impact of stage-environment fit on young adolescents’ experiences in schools and in families. American Psychologist, 48(2), 90–101.

Eccles, J. S., & Roeser, R. W. (2011). Schools as developmental contexts during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 225-241.

Elkind, D. (1967). Egocentrism in adolescence. Child Development, 38, 1025-1034.

Euling, S. Y., Herman-Giddens, M.E., Lee, P.A., Selevan, S. G., Juul, A., Sorensen, T. I., Dunkel, L., Himes, J.H., Teilmann, G., & Swan, S.H. (2008). Examination of US puberty-timing data from 1940 to 1994 for secular trends: panel findings. Pediatrics, 121, S172-91. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1813D.

Eveleth, P. & Tanner, J. (1990). Worldwide variation in human growth (2nd edition). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Gewertz, C. (2017, May 3). Is the high school graduation rate inflated? No, study says (Web log post). Education Week.

Giedd, J. N. (2015). The amazing teen brain. Scientific American, 312(6), 32-37.

Graber, J. A. (2013). Pubertal timing and the development of psychopathology in adolescence and beyond. Hormones and Behavior, 64, 262-289.

Inhelder, B. & Piaget, J. (1958). The growth of logical thinking from childhood to adolescence. NY: Basic Books.

Kena, G., Hussar, W., McFarland, J., de Brey, C., Musu-Gillette, L., Wang, X., & Dunlop Velez, E. (2016). The condition of education 2016. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics.

Klaczynski, P. (2001). Analytic and heuristic processing influences on adolescent reasoning and decision-making. Child Development, 72 (3), 844-861.

Klaczynski, P.A. & Felmban, W.S. (2014). Heuristics and biases during adolescence: Developmental reversals and individual differences. In Henry Markovitz (Ed.), The developmental psychology of reasoning and decision making, pp. 84-111. NY: Psychology Press.

Kuhn, D. (2013). Reasoning. In. P.D. Zelazo (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of developmental psychology. (Vol. 1, pp. 744-764). New York NY: Oxford University Press.

Linn, P. (2016). Risky behaviors: Integrating adolescent egocentrism with the theory of planned behavior. Review of General Psychology, 20(4), 392-398.

McGill, R.K., Hughes, D., Alicea, S., & Way, N. (2012). Academic adjustment across middle school: The role of public regard and parenting. Developmental Psychology, 48(4), 1003-1008.

Meece, J.L. & Eccles, J.S. (Eds.). (2010). Handbook on research on schools, schooling, and human development. New York, NY: Routledge.

Mendle, J., Harden, K. P., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Graber, J. A. (2010). Development’s tortoise and hare: Pubertal timing, pubertal tempo, and depressive symptoms in boys and girls. Developmental Psychology, 46,1341–1353.

Mendle, J., Harden, K. P., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Graber, J. A. (2012). Peer relationships and depressive symptomatology in boys at puberty. Developmental Psychology, 48(2), 429–435.

National Sleep Foundation. (2016). Teens and sleep. Retrieved from https://sleepfoundation.org/sleep topics/teens-and-sleep

Parker, A. K. (2013). Understanding and supporting young adolescents during the transition into middle school. In P. G. Andrews (Ed.), Research to guide practice in middle grades education, pp. 495-510. Westerville, OH: Association for Middle Level Education.

Rieff, M.I. (1998). Adolescent school failure: Failure to thrive in adolescence. Pediatrics in Review, 19(6).

Ryan, A. M., Shim, S. S., & Makara, K. A. (2013). Changes in academic adjustment and relational self-worth across the transition to middle school. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 1372-1384.

Schwartz, P. D., Maynard, A. M., & Uzelac, S. M. (2008). Adolescent egocentrism: A contemporary view. Adolescence, 43, 441-447.

Seifert, K. (2012). Educational psychology. Retrieved from http://cnx.org/content/col11302/1.2

Steinberg, L., Icenogle, G., Shulman, E.P., et al. (2018). Around the world, adolescence is a time of heightened sensation seeking and immature self-regulation. Developmental Science, 21, e12532.

Tartamella, L., Herscher, E., & Woolston, C. (2004). Generation extra large. Basic Books.

Troxel, W. M., Rodriquez, A., Seelam, R., Tucker, J. Shih, R., & D’Amico. (2019). Associations of longitudinal sleep trajectories with risky sexual behavior during late adolescence. Health Psychology. Retrieved from https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Fhea0000753

U.S. Department of Education Mentoring Resource Center (2008). Making the transition to middle school: How mentoring can help. MRC: Mentoring Resource Center Fact Sheet, No. 24. Retrieved from http://fbmentorcenter.squarespace.com/storage/MiddleSchoolTransition.pdf.

Weintraub, K. (2016). Young and sleep deprived. Monitor on Psychology, 47(2), 46-50.

Weir, K. (2015). Marijuana and the developing brain. Monitor on Psychology, 46(10), 49-52.

Weir, K. (2016). The risks of earlier puberty. Monitor on Psychology, 47(3), 41-44.

OER Attribution:

“Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective, Second Edition” by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0/modified and adapted by Ellen Skinner & Dan Grimes, Portland State University

Lifespan Development by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License/modified and adapted by Ellen Skinner & Dan Grimes, Portland State University

Additional written materials by Dan Grimes & Brandy Brennan, Portland State University and are licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-4.0

Media Attributions

- firsttimeshaving © Antiporda Productions LV, LLC is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- young-people-563026_640 © Christoph Müller

- LimbicSystem © Bruce Blaus is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- 512px-Sleeping_while_studying © Psy3330 WA is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- 22263040962_57a6478394_c © woodleywonderworks is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license