Divorce

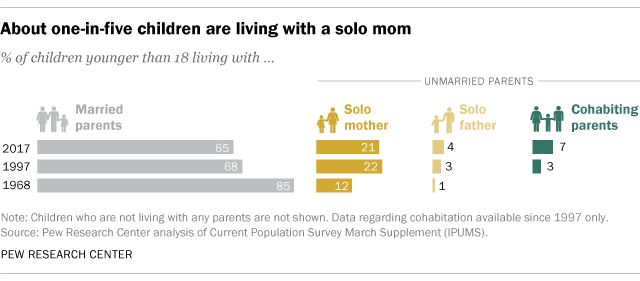

Family structures have changed significantly over the years. In 1960, 92% of children resided with married parents, while only 5% had parents who were divorced or separated and 1% resided with parents who had never been married. By 2008, 70% of children resided with married parents, 15% had parent who were divorced or separated, and 14% resided with parents who had never married (Pew Research Center, 2010). In 2017, only 65% of children lived with two married parents, while 32% (24 million children younger than 18) lived with an unmarried parent (Livingston, 2018). Some 3% of children were not living with any parents, according to the U.S. Census Bureau data.

Most children in unmarried parent households in 2017 were living with a solo mother (21%), but a growing share were living with cohabiting parents (7%) or a sole father (4%) (see Figure 4.3). The increase in children living with solo or cohabiting parents is thought to be due to overall declines in marriage, combined with increases in divorce. Of concern is that children who live with a single parent are also more likely to be living in reduced socioeconomic circumstances. Specifically, while only 8% of married couples live below the poverty line, 30% of solo mothers, 17% of solo fathers, and 16% of families with a cohabitating couple live in poverty (Livingston, 2018).

Divorce and its effects on children. Research suggests that divorce typically is difficult for children. For example, Weaver and Schofield (2015) selected a subsample of families from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development, and found that children from divorced families had significantly more behavior problems than those from a matched sample of children from non-divorced families. These problems were evident immediately after the separation and also in early and middle adolescence. An analysis of the factors that make adjustment to divorce easier or harder indicated that children exhibited more externalizing behaviors if the family had fewer financial resources before the separation. Researchers suggested that perhaps a lower income and lack of educational and community resources contributed to the stress involved in the divorce. Additional factors predicting fewer behavior problems included a post-divorce home that was more supportive and stimulating, and a mother who was more sensitive and less depressed.

Certain losses are inevitable in a divorce. Children miss the parent they no longer see as frequently, as well as any other family members who become estranged because of the divorce. Children may grieve the loss of the family as a unit, and reminisce about “the good old days” when the whole family lived together. The process of divorce is typically accompanied by change, disruption, and confusion, as well as increased family conflict. Because they are themselves dealing with the divorce, parents are typically stressed out and fewer resources are available for parenting.

Very often, divorce also means a change in the amount of money coming into the household. Custodial mothers experience a 25% to 50% drop in their family income, and even five years after the divorce they have reached only 94% of their pre-divorce family income (Anderson, 2018). As a result, children experience new constraints on spending or entertainment. School-aged children, especially, may notice that they can no longer have toys, clothing or other items to which they have grown accustomed. Or it may mean that there is less eating out or participation in recreational activities. The custodial parent may experience stress at not being able to rely on child support payments or having the same level of income as before. This can affect decisions regarding healthcare, vacations, rents, mortgages and other expenditures, and the stress can result in less happiness and relaxation in the home. The parent who has to take on more work may also be less available to the children. Children may also have to adjust to other changes accompanying a divorce. The divorce might mean moving to a new home and changing schools or friends. It might mean leaving a neighborhood that has meant a lot to them as well.

Short-term consequences. The initial consequences of divorce can be relatively serious for children. They often express anger and other indicators of distress and, and show increased problems in major areas of functioning: more unruly and demanding behavior at home, poorer school performance, and more difficulty with peers. Children may also lose some of their confidence, trust, and security in relationships. About twice as many children show serve problems following divorce (20-25%), compared to a normative base rate of about 10%. Difficulties typically peak at about one year, leading some researchers to conclude that, in terms of familial problems, the consequences of divorce are second only to parental death. However, not all children of divorce suffer negative consequences (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002). Children may be given more opportunity to discover their own abilities and gain independence that fosters self-esteem. If divorce means a reduction in family conflict, children may feel relief. Furstenberg and Cherlin (1991) believe that the primary factor influencing the way that children adjust to divorce is the way the custodial parent adjusts. If that parent is adjusting well, children will benefit. This may explain a good deal of the variation we find in children of divorce.

Child characteristics. Certain characteristics of the child can also make post-divorce adjustment easier or harder. Specifically, children with an easygoing temperament, who problem-solve well, and seek social support manage better after divorce. Children who have a difficult temperament may experience more difficulties. Boys typically display more overt problems than girls, and may increasingly act out during the transition. A further protective factor for children is intelligence (Weaver & Schofield, 2015). Children with higher IQ scores appear to be buffered from the effects of divorce. Children’s ability to deal with a divorce may also depend on their age. Infants and preschool-age children may suffer the heaviest impact from the loss of routine that the marriage offered (Temke 2006). Younger children often take divorce harder because they blame themselves; and can break their parent hearts a little if they promise to be good if only their parents will get back together again. Research has found that divorce may be most difficult for school-aged children, as they are old enough to understand the separation but not old enough to understand the reasoning behind it. Older teenagers are more likely to recognize the conflict that led to the divorce but may still feel fear, loneliness, guilt, and pressure to choose sides. Older children often turn to peers and their families to escape from their home situation.

Long-term consequences. Although children show much recovery following divorce, small effects persist. Compared to children from never-divorced families, children of divorce show lower levels of achievement in school, self-esteem, and social competence, as well as slightly elevated levels of emotional and behavioral problems (boys show externalizing and girls internalizing behavior). During adolescence, children of divorce also have slightly higher rates sexual activity and pregnancy, are less likely to graduate from high school, and more troubled romantic relationships.

To some extent, the relationships of adult children of divorce have also been found to be more problematic than those of adults from intact homes. For 25 years, Hetherington and Kelly (2002) followed a large sample of children of divorce and those whose parents stayed together. The results indicated that 25% of adults whose parents had divorced experienced social, emotional, or psychological problems compared with only 10% of those whose parents remained married. For example, children of divorce have more difficulty forming and sustaining intimate relationships as young adults, are more dissatisfied with their marriages, and consequently more likely to get divorced themselves (Arkowitz & Lilienfeld, 2013). One of the most commonly cited long-term effects of divorce is that children of divorce may have lower levels of education and occupational status (Richter & Lemola, 2017). This may be a consequence of lower income and resources for funding education rather than to divorce per se. In those households where economic hardship does not occur, there may be no impact on long-term economic status (Drexler, 2005).

Helping children adjust to divorce. According to Arkowitz and Lilienfeld (2013), long-term harm from parental divorce is not inevitable, however, and children can navigate the experience successfully. A variety of factors can positively contribute to the child’s adjustment. For example, children manage better when parents limit conflict, and provide warmth, emotional support and appropriate discipline. Further, children cope better when they reside with a well-functioning parent and have access to social support from peers and other adults. Those at a higher socioeconomic status may fare better because some of the negative consequences of divorce are a result of financial hardship rather than divorce per se (Anderson, 2014; Drexler, 2005). It is important when considering the research findings on the consequences of divorce for children to consider all the factors that can influence the outcome, as some of the negative consequences associated with divorce are due to preexisting problems (Anderson, 2014). Although they may experience more problems than children from non-divorced families, most children of divorce lead happy, well-adjusted lives and develop strong, positive relationships with their custodial parent (Seccombe & Warner, 2004).

In a study of college-age respondents, Arditti (1999) found that increasing closeness and a movement toward more democratic parenting styles were experienced following divorce. Children from single-parent families also talk to their mothers more often than children of two-parent families (McLanahan & Sandefur, 1994). Others have also found that relationships between mothers and children become closer and stronger (Guttman, 1993) and suggest that greater equality and less rigid parenting is beneficial after divorce (Stewart, Copeland, Chester, Malley, & Barenbaum, 1997).

For more information on how to help children adjust, here is guide from the American Academy of Pediatrics on Helping Children and Families Deal with Divorce.

For advice to parents, here is a set of informal recommendations.

Is cohabitation and remarriage more difficult than divorce for children? The remarriage of a parent may be a more difficult adjustment for a child than the divorce of a parent (Seccombe & Warner, 2004). Parents and children typically have different ideas about how the stepparent should behave. Parents and stepparents are more likely to see the stepparent’s role as that of parent. A more democratic style of parenting may become more authoritarian after a parent remarries. Biological parents are more likely to continue to be involved with their children jointly when neither parent has remarried. They are least likely to jointly be involved if the father has remarried and the mother has not. Cohabitation can be difficult for children to adjust to because cohabiting relationships in the United States tend to be short-lived. About 50 percent last less than 2 years (Brown, 2000). A child who starts a relationship with the parent’s live-in partner may have to sever this relationship later. Even in long-term cohabiting relationships, once it is over, continued contact with the child is rare.

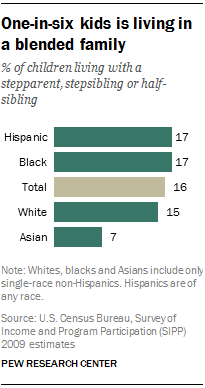

Blended families. One in six children (16%) live in a blended family (Pew Research Center, 2015). As can be seen in Figure 4.5, Hispanic, black and white children are equally likely to be living in blended families. In contrast, children of Asian descent are more likely to be living with two married parents, often in their first marriage. Blended families are not new. In the 1700-1800s there were many blended families, but they were created because one parent (usually the mother) died and the other parent remarried. Most blended families today are a result of divorce and remarriage, and such origins lead to new considerations. Blended families are different from intact families and more complex in a number of ways that can pose unique challenges to those who seek to form successful blended family relationships (Visher & Visher, 1985). Children may be a part of two households, and if each has different rules, the situation can be confusing.

Members in blended families may not be as sure that others care and may require more demonstrations of affection for reassurance. For example, stepparents expect more gratitude and acknowledgment from the stepchild than they would with a biological child. Stepchildren experience more uncertainty/insecurity in their relationship with the parent and fear the parents will see them as sources of tension. Stepparents may feel guilty for a lack of feelings they may initially have toward their partner’s children. Children who are required to respond to the parent’s new mate as though they were the child’s “real” parent often react with hostility, rebellion, or withdrawal. This occurs especially if there has not been sufficient time for the relationship to develop organically.

References

Anderson, J. (2018). The impact of family structure on the health of children: Effects of divorce. The Linacre Quarterly 81(4), 378–387.

Arditti, J. A. (1999). Rethinking relationships between divorced mothers and their children: Capitalizing on family strengths. Family Relations, 48, 109-119.

Arkowicz, H., & Lilienfeld. (2013). Is divorce bad for children? Scientific American Mind, 24(1), 68-69.

Brown, S. L. (2000). Union transitions among cohabitors: The significance of relationship assessments and expectations. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 833-846.

Drexler, P. (2005). Raising boys without men. Emmaus, PA: Rodale.

Furstenberg, F. F., & Cherlin, A. J. (1991). Divided families: What happens to children when parents part. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Guttmann, J. (1993). Divorce in psychosocial perspective: Theory and research. Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates.

Hetherington, E. M., & Kelly, J. (2002). For better or for worse: Divorce reconsidered. New York: W.W. Norton.

Livingston, G. (2018). About one-third of U.S. children are living with an unmarried parent. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/04/27/about-one-third-of-u-s-children-are-living-with-an-unmarried-parent/

McLanahan, S., & Sandefur, G. D. (1994). Growing up with a single parent: What hurts, what helps. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Pew Research Center. (2010). New family types. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2010/11/18/vi-new-family-types/

Pew Research Center. (2015). Parenting in America. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/12/2015-12-17_parenting-in-america_FINAL.pdf

Richter, D, & Lemola, S. (2017). Growing up with a single mother and life satisfaction in adulthood: A test of mediating and moderating factors. PLOS ONE 12(6): e0179639. Retrieved from https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0179639

Seccombe, K., & Warner, R. L. (2004). Marriages and families: Relationships in social context. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

Stewart, A. J., Copeland, Chester, Malley, & Barenbaum. (1997). Separating together: How divorce transforms families. New York: Guilford Press.

Temke, Mary W. 2006. “The Effects of Divorce on Children.” Durham: University of New Hampshire. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

Visher, E. B., & Visher, J. S. (1985). Stepfamilies are different. Journal of Family Therapy, 7(1), 9-18.

Weaver, J. M., & Schofield, T. J. (2015). Mediation and moderation of divorce effects on children’s behavior problems. Journal of Family Psychology, 29(1), 39-48. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/fam0000043

OER Attribution:

“Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective, Second Edition” by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0

Introduction to Sociology 2e by Rice University is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 License.

Additional written material by Ellen Skinner, Portland State University is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0