Lifespan Developmental Research Methodologies

Ellen Skinner; Julia Dancis; and The Human Development Teaching & Learning Group

Learning Objectives: Lifespan Developmental Methodologies

- Explain the importance of complementary multidisciplinary methodologies and converging operations.

- Recognize the steps in deductive, inductive, and collaborative methodologies.

- Be familiar with the many methods developmentalists use to gather information, including observations and self-reports, psychological tests and assessments, laboratory tasks, psychophysiological assessments, archival data or artifacts, case studies, and enthnographies.

- Identify the general strengths and limitations of different methods (e.g., reactivity, social desirability, accessibility, generalizability).

Because interventionists and practitioners use bodies of scientific evidence to transform systems and change practices in the world, it is crucial that researchers produce the highest quality evidence possible, and evaluate and critique it thoughtfully. The tools that scientists use to generate such knowledge are called research methods or methodologies. Many textbooks describe “the” scientific method, as if there were only one way of knowing scientifically. Just as lifespan development spans multiple disciplines, each with their own preferred epistemologies and methodologies, we believe that there are multiple scientific methods, or multiple perspectives, each one providing a complementary line of sight on a given target phenomenon. Social and developmental sciences have been critiqued for our reliance on a narrow range of methodologies, favoring methods that quantify observations (e.g., via surveys, ratings, or numerical codings) and control extraneous variables or confounds, either statistically or, for example, by bringing people into the lab. Social scientists often seem to favor these more quantitative methods, and to discount methodologies that are more situated, contextualized, and wholistic, sometimes called qualitative methods.

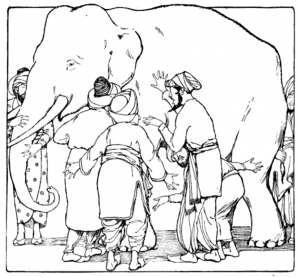

However, it has become clear that these methodologies are not antagonistic. Instead, they are complementary ways of knowing or lines of sight on target phenomena, each whole and important in its own right, but incomplete. We think about these multiple perspectives the same way that they are described in the parable of the six blind men and the elephant. In this story, each person makes contact with a different part of the elephant and comes to his own conclusions– the one who encounters its legs explains that elephants are tree trunks, the ears reveal it to be a fan, the flank a wall, the tail a rope, the trunk a snake, and the tusk a spear.

Each one’s understanding is correct, but unknown to all of them, each is also incomplete. They need the views from all of these perspectives, what we sometimes call 360o lines of sight, to fully appreciate the elephant in its wholeness and complexity. In the same way, multiple cross-disciplinary, inter-disciplinary, and multi-disciplinary methodologies are needed to understand our developmental phenomena in their wholeness and complexity. We find a lifespan developmental systems perspective especially useful in articulating this view (Baltes, Reese, & Nesselroade, 1977; Cairns, Elder, & Costello, 2001; Lerner, 2006; Overton, 2010; Overton & Molenaar, 2015; Skinner, Kindermann, & Mashburn, 2019). The best research and graduate training programs in human development teach their doctoral students about a wide range of epistemologies and methodologies and see them all as parts of “converging operations.”

What is meant by converging operations?

This was an idea, brought to the attention of developmentalists almost 50 years ago (Baer, 1973), to help deal with the unsettling realization that every method ever devised to conduct scientific studies has serious shortcomings. The main idea is that good science needs a wide variety of differing methodologies, so that the strengths of one can compensate for the limitations of others. From this perspective, a body of evidence is much stronger when findings from multiple complementary methodologies converge on the same conclusions. That is why we favor developmental science that incorporates methodologies from many disciplines, and continues to question and critique those methodologies as part of its reflective practice.

Deductive Methodologies

In discussions of scientific methods, the procedure that is often highlighted is the deductive method— in which a scientist starts with a falsifiable hypothesis and then conducts a series of observations to test whether the specifics on the ground are consistent with this hypothesis. In this process, the scientist foregrounds “thinking” (the theory) and follows this up with figuring out how to “look” (i.e., conduct the study or observation) in ways that test the validity of this theory. This process unfolds in multiple recursive or circular steps, including:

- Formulate a question. Use initial observations to articulate a research question:

- Review previous studies (known as a literature review) to determine what has been found to date

- Identify the deficiencies or gaps in previous research

- Formulate a working theory of the target phenomenon and propose a hypothesis

- Conduct a study. Select or create a method of gathering information relevant to the hypothesis:

- Who? Sampling. Determine the people to be included

- What? Measurement. Determine the measures to be used to capture the phenomena of interest

- Where? Setting. Determine the setting where the study will take place

- How? and When? Design. Determine the study design

- Interpret the results. In light of everything you know, examine what the findings likely mean:

- Consider the limitations of the study

- Draw conclusions, including rejecting the hypothesis and revising the original theory

- Suggest future studies

- Publish. Make the findings available to others:

- Share information with the scientific community

- Invite scrutiny of work by other experts

Inductive Methodologies

A second set of procedures is more inductive. This process, often called grounded theory, starts with a general question and then constructs a theory of the phenomenon based, not on the scientific community’s or researcher’s preconceived notions, but on the researcher’s actual observations of many specific experiences on the ground. As you can see, in the process, the scientist foregrounds “looking” (the observations and experiences in the target setting) and uses this process to scaffold “thinking” (i.e., theorizing or building a mental model of what has been observed). This process also unfolds in multiple recursive or circular steps, including:

- Find a question. Begin with a broad area of interest and identify a research problem:

- Review the literature to justify the importance of the problem

- See how the problem fits into a larger set of issues

- Identify the deficiencies or gaps in other work on the topic

- Gather information. Through extended first hand engagement, learn about the target:

- Who? and Where? Gain entrance into a group and natural setting relevant to the problem of study

- What? Ask open-ended, broad “grand tour” types of questions when interviewing and observing participants; focus on participant perspectives

- How? Gather field notes about the setting, the people, the structure, the activities or other areas of interest; collect artifacts, pictures

- Reflect. Modify research questions as the study evolves and follow the emergent questions

- Make sense of the information. In light of all the specifics, reflect on what your observations likely mean:

- Note own participation and biases

- Note patterns or consistencies, uncover themes, categories, interrelationships

- Focus on centrality of meaning of the participants

- Explore new areas deemed important by participants

- Report findings. Put together a coherent narrative that incorporates the themes and connections uncovered

- Check back in with participants to get their perspectives on your interpretations

- Publish. Make the findings available to others:

- Share information with the scientific community

- Invite scrutiny of work by other experts

Collaborative Methodologies

A third set of methodologies is based on the assumption that knowledge, research, and effective social action can best be co-constructed among researchers and community participants, incorporating the strengths and perspectives of all the stakeholders involved in a particular set of issues. This approach, often called community-based participatory action research, holds that complex social issues cannot be well understood or resolved by “expert” research, pointing to interventions from outside of the community which often have disappointing results or unintended side effects. In collaborative approaches, researchers and community partners build a genuine trusting relationship, and this cooperative partnership is the basis on which all decisions about the project are made: from articulating a set of research questions, to identifying data collection strategies, analysis and interpretation of information, and dissemination and application of findings.

The process is inherently:

- Community-based. Researchers build a collaborative partnership with community members who are already living with, involved in, or working on the problem of interest. Hence, this work is situated within neighborhoods and community organizations or groups, and builds on their strengths and priorities. Instead of taking individuals out of communities and into lab settings for study or providing individualized therapy to “fix” broken individuals, the goal of this work is to help facilitate change within the community itself, making it a more supportive context for all its inhabitants.

- Participatory. As the collaboration develops, members discuss and learn more about each other so that together they can co-create and frame a common agenda for research and action. These projects incorporate researchers’ expertise and goals, but they foreground the knowledge, concerns, and needs of community partners. For example, researchers interested in homeless youth could reach out to youth-serving organizations and begin conversations exploring whether they would like to work together. These conversations would also soon involve the homeless youth themselves, consistent with the slogan popularized by the disability rights movement, “Nothing about us without us!” Community knowledge is considered irreplaceable as it provides key insights about target issues.

- Action. All research activities are anchored and oriented by the larger goal of enhancing strategic action that leads to social change and community transformation as part of the research program. Community action make take the form of public education surrounding community issues (e.g., information campaigns, teach-ins), changing existing policies that harm groups of people (e.g., harsh discipline policies at school), creating new public spaces (e.g., community gardens and farmers’ markets), and so on.

- Research. The community action plan is informed by organizing existing information and collecting new information from key stakeholders relevant to the community issues under scrutiny. Methods to conduct these studies are planned together in ways that researchers believe will produce high quality information and that collaborators believe will be useful to them in making progress on their agenda. All partners are also involved in the scrutiny, visualization, discussion, and interpretation of data, and make joint decisions about how it should be disseminated and used going forward. These efforts feed into next steps in both research and action.

- Ongoing collaboration. Such university-community partnerships typically last for many years. Researchers are thoughtful about how to bring them successfully to a close, making sure that an ongoing goal of the collaboration is to build capacity within the community partnership so members can sustain collective action after the research team leaves.

A good way to become more familiar with these collaborative, inductive, and deductive research methods is to look at journal articles. You will see that they are written in sections that follow the steps in the scientific process. In general, the structure includes: (1) abstract (summary of the article), (2) introduction or literature review, (3) methods explaining how the study was conducted, (4) results of the study, (5) discussion and interpretation of findings, and (6) references (a list of studies cited in the article).

Methods of Gathering Information

“Methods” is also a name given to many different procedures scientists use to make their observations or collect information. Since developmentalists are interested in a wide range of human capacities, they want to know not only about people’s actions and thoughts, as expressed in words and deeds, but also about underlying processes, like abilities, emotions, desires, intentions, and motivations. Moreover, they want to go deeper, looking into biological and neurophysiological processes, and they want to consider many factors outside the person of study, looking at social relationships and interactions, as well as environmental materials, tasks, and affordances, and societal contexts. And, as lifespan researchers, they want to study these capacities at all ages, from the tiniest babies to the oldest grandmothers. No wonder developmental scientists need so many tools, and are inventing more all the time.

Every time you come across a conclusion in a textbook or research article (for example, when you read that “18-month-olds do not yet have a sense of self”), you should stop and ask, “How do you know that?” That is a great question. And a great scientific attitude. Over and over, we will want to scrutinize the evidence scientists are using to make their conclusions, considering carefully the extent to which the methods scientists use justify the conclusions they make. If a baby can’t yet talk, how would we know whether they have a sense of self? And even when a child can talk, what is the connection between what they are telling us and what they are truly thinking? You can be sure that these kinds of questions stoke lively debates in scientific circles.

As with methodologies more generally, science is strengthened by the use of a variety of approaches to collecting information. The shortcomings of one can be compensated for by the strengths of others. If we find that a new mother says that she is feeling stressed, and her best friend agrees, and we see elevated cortisol levels, and her survey results are higher than usual, and she becomes irritated when her two-year-old makes a mess– well, we think we have captured something meaningful here. We are always in favor of multiple sources of data, and we especially appreciate methods that get us thick, rich information, as close to lived experience in context as possible.

Here are some examples of methods commonly used in developmental research today:

Observations: Looking at People and their Actions

Often considered the basic building blocks of developmental science, observational methods are those in which the researcher carefully watches participants, noting what they are doing, saying, and expressing, both verbally and nonverbally. Researchers can observe participants doing just about anything, including working on tasks, playing with toys, reading the newspaper, or interacting with others. Observations are ideal for gathering information about people’s verbal and physical behavior, but it is less clear whether internal states, like emotions and intentions, can be unambiguously discerned through observation.

- Naturalistic observations take place when researchers conduct observations in the regular settings of everyday life. This method allows researchers to get very close to the phenomenon as it actually unfolds, but researchers worry that their participation may impact participants’ behaviors (a problem called reactivity). And, since researchers have little control over the environment, they realize that the different behaviors they observe may be due to differences in situational factors.

- Laboratory observations, in contrast, take place in a specialized setting created by the researcher, that is, the lab. For example, researchers bring babies and their caregivers to the lab in a systematic procedure known as the strange situation, which you will learn about in the section on attachment. Observing in the lab allows researchers to set up a specific space and to have control over situational factors. However, researchers worry that the artificial nature of the situation may have an impact on people’s behavior, and that the behaviors people show in the lab are not typical of the ones they show in regular contexts of daily life (a problem called generalizability).

- Video or audio observations can be gathered using automatic recording devices that collect information even when a researcher is not present. For example, researchers ask caregivers to record family dinners or teachers to tape class sessions; or place a small recording device on a young child’s chest that records every word the child says or hears. These records can then be watched or listened to by researchers. Such procedures reduce reactivity, but the resultant recordings are narrower in scope than what researchers could hear or see if they were present observing in the actual context.

- Local expert observers can provide researchers with information about the verbal and non-verbal behavior of participants they have observed or interacted with many times. For example, caregivers and teachers can report on their children and students, and even children can provide their perspectives. Reports from others typically incorporate many more observations than a researcher could collect (e.g., a teacher sees a child in class every week day), so the information is more representative of the target’s typical behavior. However, researchers worry that information could be distorted, for example, because reporters are biased or are not trained to observe or categorize the behaviors they have witnessed.

- Participant observations, which are especially common in anthropology and sociology, take place when researchers gain entrance into a setting, not as an observer, but as a participant, with the aim of gaining a close and intimate familiarity with a given group of individuals or a particular community, and their behaviors, relationships, and practices. These observations are usually conducted over an extended period of time, sometimes months or years, which means that the observer can directly observe variations and changes in actions and interactions. Such observations provide rich and detailed information, but are limited to the specific setting.

Self-reports: Listening to People and their Thoughts

When researchers are studying people, one of the most common ways of gathering information about them is by asking them, via self-report methods. These can range from informal open-ended interviews or requests for participants to write responses to prompts, all the way to surveys, when participants can only choose among researcher-generated options. Self-report data are ideal for learning about people’s inner thoughts or opinions, but researchers worry that participants may distort the truth to present themselves in a favorable light (a problem called social desirability). There is also debate about whether participants have access to some of their internal processes, like their genuine motivations.

- Surveys gather information using standardized questionnaires, which can be administered either verbally or in writing. Surveys capture an enormous range of psychological and social processes, and their items can be tested for their reliability and validity (called psychometric properties), but they typically yield only surface information. Researchers worry that participants may misinterpret questions and realize that the information so collected is restricted to exactly those pre-packaged questions and responses.

- Standardized, structured, or semi-structured interviews involve researchers directly asking a series of predetermined questions. Because researchers are present, they can ask follow up questions and participants can ask for clarification. This allows researchers to learn more from participants than they could from standardized questionnaires, but researchers worry that their presence could cause reactivity, such as when participants want to provide more socially desirable responses in a face-to-face setting than on an anonymous survey.

- Open-ended interviews typically use targeted questions or prompts to get the conversation flowing, and then follow the interview where ever it leads. This allows for more customized questioning and in-depth answers, as researchers probe responses for greater clarity and understanding. However, since each respondent participates in a different interview conversation, it can be difficult to compare responses from person to person.

- Focus groups involve group open-ended interviews, in which a small number of people (6-10) discuss a series of questions or prompts in guided or open discussion with a trained facilitator. In this format, focus group members listen and can react to each other’s comments and build discussion at the group level.

- Responses to prompts are used when researchers ask participants to write down their thoughts. These can range from relatively unstructured free writes to short answers to a series of well-structured questions. Daily diaries, often organized electronically, allow participants to respond to online questions or prompts many days in a row.

Psychological Tests and Assessments: Mental Capacities and Conditions

Most of us are familiar with tests that measure, for example, IQ or other mental abilities, and with diagnostic assessments that classify people according to psychological conditions. When you read about the aging of intelligence, for example, some of those studies utilize measures of crystalized and fluid intelligence. Tests to measure mental abilities have been created for people of all ages, although it is not always clear how the measures used at different ages are connected to each other.

Laboratory Tasks: Interactions that Elicit or Capture Psychological Processes

Researchers create and invent all manner of tasks for participants to work on, either in the lab or in real life settings (e.g., at home or school). These tasks allow researchers to set up activities that can assess a range of psychological attributes for people of all ages, ranging from problem-solving abilities to regulatory capacities (e.g., using the “Heads, Shoulders, Knees, and Toes” task), prosocial behaviors, learned helplessness, theories of mind, social information processing, rejection sensitivity, and so on. Many YouTube videos show children and adolescents participating in these tasks, and it is instructive to try to figure out exactly what is captured in each one. If you would like to see an example, you can watch a video of The Shopping Cart Study (not required, bonus information).

Psychophysiological Assessment: Underlying Neurophysiological Functioning

Researchers also use a range of methods to capture information about neurophysiological functioning across the lifespan, including technology that can measure heart rate, blood pressure, hormone levels, and many kinds of brain activity to help explain development. These assessments provide information about what is happening “under the skin,” and researchers can see how these biological processes are connected to behavioral development. Usually connections are bidirectional– neurophysiology contributes to the development of behavior, and behaviors shape physiological functioning and development.

Archival Data or Artifacts: Information from Business as Usual

Researchers sometimes utilize information that has already been collected as a regular part of daily life. Such data include, for example, students’ grades and achievement tests scores, documents or other media, drawings, work products, or other materials that might provide information about participants’ developmental progress or causal factors contributing to their development. These kinds of data have the advantage of low reactivity and high authenticity, in that they were created or gathered in the normal course of events, but it is sometimes unclear exactly what they mean or what constructs they measure.

Case Study: All of the Above with Carefully Selected Participants or Settings

One of the best ways to gather in depth information about a person or group of people (e.g., a classroom, school, or neighborhood) is through a research methodology called the case study. Researchers focus on only one or a small number of target units, usually carefully selected for specific characteristics (e.g., an individual identified as wise, a homeless teenager, a very effective school, or a workplace with high turnover rates), and amass everything they can about that person or place. Researchers typically conduct in-depth open-ended interviews with people, including friends or family of the target person, and collect archival data and artifacts, which they might discuss in depth with participants. For example, they might go through the person’s photo albums and discuss memories of their early life. Classical examples of case studies are the so-called baby diaries, in which researchers like Jean Piaget and William Stern conducted extensive observations on their individual children and took detailed notes about every aspect of their behavior and development. They also tested some of their hypotheses about development, by giving their babies toys to play with or engaging them in interesting tasks. These case studies were conducted over years. When case studies also extend into the past of the individual (for example, when researchers are interested in life review processes), they can be called biographical methods.

Sometimes researchers who focus on a group of individuals or a setting are particularly interested in the cultural context and its functioning. These studies can be called ethnographies. Drawn originally from anthropology, ethnographic methods describe an approach in which researchers carefully study and document people and their cultural settings, usually through extensive participant-observation, interviews, and engagement in the setting. In these studies, as in all scientific investigations, researchers are the students and the people in the setting are the teachers. Researchers strive to create a wholistic, higher-order narrative account that privileges the perspectives of the people studied.

Take Home Messages about Lifespan Developmental Methodologies

We would highlight four main themes from this section:

- Because interventionists and practitioners use bodies of scientific evidence to transform systems and change practices in the world, it is crucial that researchers produce the highest quality evidence possible, and evaluate and critique it thoughtfully.

- Developmental science incorporates multiple methodologies from many disciplines, and these deductive, inductive, and collaborative methodologies make our conclusions stronger because they provide complementary lines of sight on our target phenomena.

- Science is also strengthened by the use of a variety of approaches (or methods) for collecting information, including observations, self-reports, and other strategies, because together they provide a richer picture of our target developing phenomena.

- The advantages of using multiple methodologies and sources of information are highlighted by the idea of “converging operations,” which points out that this practice allows the shortcomings of one method to be compensated for by the strengths of others, and reminds us that bodies of evidence are stronger when findings from multiple complementary methodologies and sources of information converge on the same conclusions.

References

Baer, D. M. (1973). The control of developmental process: Why wait? In J. R. Nesselroade & H. W. Reese (Eds.), Lifespan developmental psychology: Methodological issues (pp. 187-193). New York: Academic Press.

Baltes, P. B., Reese, H. W., & Nesselroade, J. R. (1977). Life-span developmental psychology: Introduction to research methods. Oxford, England: Brooks/Cole.

Cairns, R. B., Elder, G. H., & Costello, E. J. (Eds.). (2001). Developmental science. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lerner, R. M. (2006). Developmental science, developmental systems, and contemporary theories of human development. In R. M. Lerner (Vol. Ed.) and R. M. Lerner & W. E. Damon (Eds-in-Chief.). Handbook of child psychology: Vol 1, Theoretical models of human development(pp. 1-17). John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Overton, W. F. (2010). Life‐span development: Concepts and issues. In W. F. Overton (Vol. Ed.) R.M. Lerner (Ed.-in-Chief), The handbook of life-span development: Vol. 1. Cognition, biology, and methods (pp. 1-29). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Overton, W. F., & Molenaar, P. (2015). Handbook of child psychology and developmental science (R. M. Lerner, Ed.-in-Chief): Vol 1, Theory and method. John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Skinner, E. A., Kindermann, & Mashburn, A. J. (2019). Lifespan developmental systems: Meta-theory, methodology, and the study of applied problems. An Advanced Textbook. New York, NY: Routledge.