Maltreatment, Adversity, and Resilience

“Adverse childhood experiences are the single greatest unaddressed public health threat facing our nation today.” — Dr. Robert Block, former President of American Academy of Pediatrics

Since the inception of the field over a century ago, developmental researchers have examined the potentially harmful effects of early childhood experiences on development. Following the historical trends of their day, developmentalists investigated the impact of maternal separation due to war, hospitalization, and death; the effects of institutional care; and the multiple risks experienced by children living in poverty (e.g., Evans, 2004). As certain topics lost their taboo and moved into the mainstream, researchers focused more closely on problems that can interfere with family functioning, like divorce, maternal depression and other forms of mental illness, familial substance abuse, intimate partner violence, incarceration, and child neglect and maltreatment. Adverse experiences rooted in family functioning are especially problematic for children because they not only create stressful experiences, but they can also disrupt the primary systems (i.e., parenting and family) that are supposed to protect and buffer children from major stressors.

Adversity and resilience. To make sense of research on the developmental consequences of divorce, maltreatment, and other adverse childhood experiences (several of which are covered later in this reading and in class), we rely on a framework organized around the twin concepts of adversity and resilience. The notion of adversity highlights the genuine impact of early traumatic childhood experiences. Such clarity can be useful to people who experienced such events as children, helping them make sense of the way past events may be continuing to vibrate in their bodies and minds. For example, research documenting common neurophysiological effects of adverse experiences is useful to survivors because it can alert them to some of the behavioral and emotional outcomes they may already be experiencing (e.g., increased stress reactivity, emotional dysregulation, impulsivity, vulnerability to substance abuse). It verifies that what happened to them is real and serious, but not their fault. These are side-effects of their early life experiences and not evidence of character defects or lack of self-control.

The notion of resilience is complementary to adversity, and focuses on the strength and buoyancy of developmental systems in the face of extreme stress. In order to motivate widespread efforts to eliminate adverse childhood experiences, researchers and practitioners rightly underscore the severity of their harmful effects on child development. Such messages, however, can inadvertently communicate to adults whose childhoods included these experiences, especially those exposed to multiple adverse experiences, that they should be pessimistic about their own developmental prospects. Nothing could be further from the truth. Research documents enormous capacity for healing and recovery at every age. In other words, frameworks that focus only on harms of adverse experiences often make their effects seem toxic and inevitable, while underplaying the hardiness and resilience of developmental systems even in the face of serious adversity. Most useful are frameworks that consider both adversity and resilience as two sides of the same coin.

In the following sections, we present research on child abuse (also called maltreatment), then describe and critique a perspective on adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) that is currently popular for both research and practice, and finish by exploring some of the processes of resilience that are shown by individuals and their communities.

Child Maltreatment

The Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act defines Child Abuse and Neglect as: Any recent act or failure to act on the part of a parent or caretaker which results in death, serious physical or emotional harm, sexual abuse or exploitation; or an act or failure to act, which presents an imminent risk of serious harm (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2020). Each state has its own definition of child abuse based on the federal law, and most states recognize four major types of maltreatment: neglect, physical abuse, psychological maltreatment, and sexual abuse. Each of the forms of child maltreatment may be identified alone, but they can occur in combination.

Prevalence of Child Abuse. According to the United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) (2019), during 2017 (the most recent year data has been collected) Child Protective Services (CPS) agencies received an estimated 4.1 million referrals for abuse involving approximately 7.5 million children. This is a rate of 31.8 per 1,000 children in the national population. Professionals made 65.7% of alleged child abuse and neglect reports, and they included law enforcement (18.3%), educational (19.4%) and social services personnel (11.7%). Nonprofessionals, such as friends, neighbors, and relatives, submitted 17.3% of the reports. Approximately 3.5 million children were the subjects of at least one report.

Child abuse comes in several forms. By far the most common is neglect (78%; United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2013), followed by physical abuse (18%), sexual abuse (9 percent), psychological maltreatment (8.5%), and medical neglect (2.3%). Some children suffer from a combination of these forms of abuse. The majority of perpetrators are parents (80.3%) or other relatives (6.1%). The majority of victims consisted of three ethnicities: White (44.6%), Hispanic (22.3%), and African-American (20.7%). Children in their first year of life had the highest rate of victimization (25.3 per 1,000 children of the same age). In 2017 an estimated 1,720 children died from abuse and neglect, and 71.8% of all child fatalities were younger than 3 years old. Boys had a higher child fatality rate (2.68 per 100,000 boys), while girls died of abuse and neglect at a rate of 2.02 per 100,000 girls. More than 88% of child fatalities were comprised of White (41.9%), African-American (31.5%), and Hispanic (15.1%) victims (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2019).

Sexual abuse. Childhood sexual abuse is defined as any sexual contact between a child and an adult or a much older child. Incest refers to sexual contact between a child and family members. In each of these cases, the child is exploited by an older person without regard for the child’s developmental immaturity and inability to understand the sexual behavior (Steele, 1986). Research estimates that 1 out of 4 girls and 1 out of 10 boys have been sexually abused (Valente, 2005). The median age for sexual abuse is 8 or 9 years for both boys and girls (Finkelhorn, Hotaling, Lewis, & Smith, 1990). Most boys and girls are sexually abused by a male. Although rates of sexual abuse are higher for girls than for boys, boys may be less likely to report abuse because of the cultural expectation that boys should be able to take care of themselves and because of the stigma attached to homosexual encounters (Finkelhorn et al., 1990). Girls are more likely to be abused by family member and boys by strangers. Sexual abuse can create feelings of self-blame, betrayal, shame and guilt in children (Valente, 2005). Sexual abuse is particularly damaging when the perpetrator is someone the child trusts. Meta-analyses of the long-term effects of childhood sexual abuse indicate that survivors have an small increased lifetime risk for some physical and mental health conditions (e.g., depression, anxiety, problems with intimacy, and suicide), but that much recovery is possible (Chen et al., 2010; Hillberg, Hamilton-Giachritsis, & Dixon, 2011; Irish, Kobayashi, & Delahanty, 2010; Valente, 2005). The presence and severity of long-term effects depend on a host of factors, including the nature and duration of the abuse, and the co-occurance of other forms of negect or maltreatment. Sexual abuse is considered a serious adverse childhood experience, but consistent with work on resilience, most survivors experience much recovery once the abuse has been terminated and some show no lasting harmful effects.

Effects of toxic stress on young children. Children experience different types of stressors. Normal, everyday stress can provide an opportunity for young children to build coping skills and poses little risk to development. Even more long-lasting stressful events, such as changing schools or losing a loved one, can be managed fairly well. However, when children experience chronic neglect or abuse over long periods of time, researchers refer to this as toxic stress because it can produce long-lasting effects. Some of the most concerning are neurobiological (see box, below). Young children exposed to violence and aggression may blame themselves for neglect or abuse. Children with a history of maltreatment may also show disturbances in attachment, delays in cognitive and language development, as well as deficits in behavioral and emotional self-regulatory skills.

Long-term, neurophysiological impairments can contribute to higher stress reactivity, emotional dysregulation (e.g., anxiety and depression), and social difficulties such as problems relating to others, lower levels of empathy and sympathy, poorer social skills and peer relationships. Neurobiological impairments may also undermine cognitive development, including working memory and executive functioning, contributing to poorer academic motivation and performance. By adolescence, children with a history of abuse are more likely to show aggressive anti-social behavior, substance abuse, and involvement in delinquency, gangs, and violent crime. Given the complex nature of abuse, it is often difficult to sort out the precise mechanisms of effects.

The current prevalence of maltreatment underscores the need for more research on processes of healing, recovery, and resilience during adolescence and adulthood. Especially encouraging are studies focusing on reversal of and recovery from some of the biobehavioral impairments associated with early exposure to toxic stress. For example, studies of the long-term effects of massive trauma such as was experienced by some infants in Romanian orphanages has shown the healing power of subsequent experiences in stable, loving, and enriched homes (e.g., Audet & Le Mare, 2011). At the same time, research documenting the potentially serious and negative long-term effects associated with childhood maltreatment underscore the importance of efforts to prevent, detect, stop, and treat neglect and abuse at the youngest ages possible, using all the public health tools at our disposal.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

Over the last 20 years, a framework has become popular that gathers up a variety of sources of early stress, and considers them together as adverse childhood experiences (or ACEs; CDC, 2019; Merrick, Ford, Ports, & Guinn, 2018; Petruccelli, Davis, & Berman, 2019). This area of study was initiated when researchers created a scale that listed the most common of these early developmental risks (i.e., neglect; verbal, physical, and sexual abuse; and family dysfunction based on mental health, substance abuse, and domestic violence) and asked adults to report whether they had experienced any of them before they turned 18. Researchers then counted the number of experiences (creating an index of cumulative risk) and examined whether people with different numbers of ACEs also showed differences in physical or psychological functioning. This line of work revealed two things: ACEs are common– about 70% of adults have experienced at least one, and 25% at least three. And the number of ACEs, especially when it reaches 4 or more, is a strong predictor of a range of psychological and physical health problems. Researchers sometimes even estimate the cost of ACEs in the number of years they subtract from a person’s average life expectancy.

By drawing together events as diverse as maternal death and physical abuse, researchers have learned that these experiences tend to co-occur and that their effects are cumulative. This means, for example, that intimate partner violence is often accompanied by maternal depression, neglect, and physical abuse; and it is this combination of events that take their toll. This suggests that it is not possible to understand the effects of any one adverse experience without considering the entire profile to which a child has been exposed. The more chronic and widespread the experiences, the more serious their impact on development.

Moreover, an overarching framework has allowed researchers who study different kinds of adversity to realize that many of these early experiences influence subsequent development through a common set of pathways. Many of these experiences interfere with the healthy development of the neurophysiological systems that deal with stress. The two primary pathways through which early adversity registers in long-term health effects seem to be (1) increases in behavioral risk, in which changes in brain systems render individuals more susceptible to substance abuse and other behaviors that pose health risks; and (2) over and above the effects of risky behaviors, early insult to the immune and other biological system leads to greater vulnerability to health conditions later in life (e.g., cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, and autoimmune conditions like asthma).

Neurophysiological effects of early adversity. The stress systems that govern “fight-flight-or-freeze” responses are complex, and involve the endocrine and immune systems; the centers of the brain that regulate fear (e.g., the amygdala), pleasure (e.g., the nucleus accumbens), and memory (e.g., the hippocampus); and the brain areas that that serve intentional self-regulation, decision-making, and planning. (i.e., the prefrontal cortex).When children are chronically overwhelmed by stress, the healthy development of all of these neurobiological systems can be compromised, often at the epigenetic level. An impaired stress regulation system interferes broadly with normal cognitive, social, emotional, and physical development and may even undermine long-term psychological and physical health and functioning.

ACEs are found across all demographic groups, but as you might expect from readings on higher-order contexts, those who are low income or de-valued by society may be at higher risk: A study by Merrick and colleagues (2018) found significantly higher ACE exposure for those who identified as Black, multiracial, lesbian/gay/bisexual, or reported being low income or unemployed or having less than a high school education.

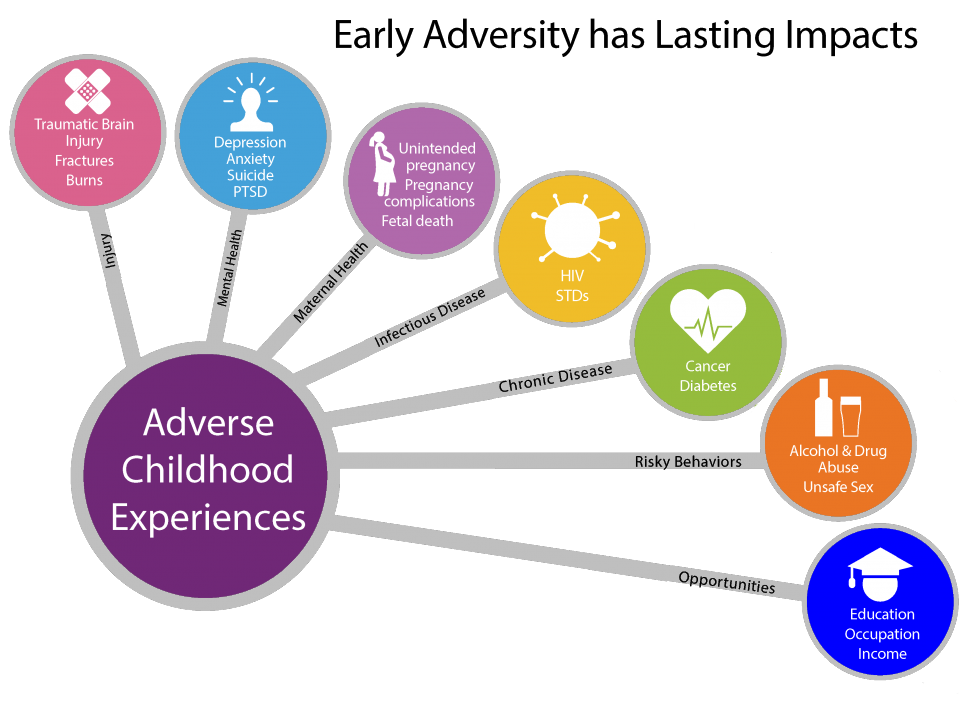

Images like this, which highlight long term physical, psychological, and society risks associated with adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are helpful in highlighting how important it is to prevent ACEs and support people who have experienced them. An unintentional effect of such images can be making it seem like early adversity inevitably leads to these outcomes—which is not the case. It is important to consider the role of factors that protect and buffer children as well as the incredible human capacity for resilience and recovery.

Early prevention and intervention. By connecting ACEs to later physical health, this framework has captured the attention of pediatricians, who have come to view the prevalence of early adversity as a major public health crisis. Many pediatricians call for early detection and treatment by routinely screening for ACEs as part of children’s well-baby visits starting in infancy (e.g., see Dr. Nadine Burke Harris’ TED Talk). Pediatricians often screen mothers retrospectively for ACEs as well, and argue for “two generation” treatment in which they work to prevent traumatization of young children by treating the effects of ACEs in their mothers.

This screening also provides an entry point for engaging at-risk mothers in reflection about their own childhoods and the childhoods they wish to provide for their infants. Research documenting the effects of screening is just beginning (Ford et al., 2019), but meta-analyses of interventions designed to reduce the biological impacts of childhood adversity are promising (Boparai et al., 2018). Multicomponent interventions target the reduction of ACEs by utilizing professionals to provide parenting education, mental health counseling, social service referrals, and social support. Such programs, which largely target children aged 0-5 years, have been shown to both improve parent-child relationships and reduce reduce/reverse many neurophysiological effects in children.

Critiques of the ACEs framework. Although the ACEs framework has been useful for practice, it has received a great deal of criticism from researchers, largely because it oversimplifies the study of early adversity. Critiques include controversy about what qualifies as an ACE, whether counting is sufficient to account for the interactions among different ACEs, and the exclusion in its calculations of any positive childhood experiences that could protect or buffer children from some or all of these neurobiological impacts (Lacey & Minnis, 2020; Sege & Browne, 2017). Many researchers also point out the problems with retrospective studies (e.g., people currently in a negative state can more easily recall negative childhoods events). As a result, most researchers call for more prospective longitudinal studies that examine different kinds of adverse experiences separately. They point out that the effects of different events, like divorce versus sexual abuse, may be quite different; and that it is important to examine both the severity and chronicity of these events as well as their combination with other positive and negative experiences. As these more differentiated programs of study progress, the ACEs perspective could then provide an integrative framework within which these strands of work could be compared, contrasted, and eventually woven together.

Resilience

Just as important as research on adversity is the study of resilience. To date, such research reveals that, no matter the adversity, there is always room for recuperation, gains, and work-arounds to foster improvement in mental and physical functioning. For example, a recent framework, called “HOPE: Health Outcomes from Positive Experiences” focuses on four broad categories of experiences that can buffer the effects early adversity and contribute to healthy development and wellbeing: (1) nurturing, supportive relationships; (2) living, developing, playing, and learning in safe, stable, protective, and equitable environments; (3) having opportunities for constructive social engagement and connectedness; and (4) learning social and emotional competencies (Sege & Browne, 2017). In fact, the same brain characteristics that contribute to early vulnerability (i.e., malleability, meaning that the brain’s development is open to the effects of adverse experiences) also contribute to later resilience. Such “neuroplasticity” means that the developing brain can also be reshaped by subsequent positive experiences, in this case, enriching and healing social, physical, and psychological experiences. Continued exploration of the most effective components of treatment, and whether they are age-graded, is an important topic of study in this area.

Societal responsibility for ACEs. As research on ACEs has become more popular, it has been subject to another major critique that also applies to all the other areas of study that focus on child maltreatment: Such work typically fails to acknowledge the role that societal factors play in creating and enabling harmful childhood experiences (e.g., Cox et al., 2018; Walsh, McCartney, Smith, & Armour, 2019). The single biggest predictor of family dysfunction and child maltreatment is the toxic stress of poverty. In the US, poverty is overrepresented in families from ethnic/racial minority backgrounds and in female-headed households, and these subgroups are subject to additional stressors and inequities based on prejudice and discrimination.

As discussed in the reading from the previous class on higher-order contexts of parenting, such hazardous conditions exert a downward pressure on people’s capacity to provide for a family and take care of children. Although most poor and minority parents accomplish these tasks successfully, it is very challenging to protect and buffer children from all of these potential risks. The developmentally dangerous conditions in which many poor children are raised can be thought of as societally-sanctioned in that society has agreed that children should only receive as many of the developmental basics they need, such as food and shelter, as their families can afford. One way to significantly reduce the prevalence of ACEs would be to enact societal policies that reduce poverty. Given the expenses otherwise incurred by potential long-term behavioral and medical outcomes, such policies would not only protect and promote child health and development, they would also save a great deal of money

References

American Psychological Association. (2019). Immigration. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/advocacy/immigration

Audet, K., & Le Mare, L. (2011). Mitigating effects of the adoptive caregiving environment on inattention/overactivity in children adopted from Romanian orphanages. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 35(2), 107-115.

Boparai, S. K. P., Au, V., Koita, K., Oh, D. L., Briner, S., Harris, N. B., & Bucci, M. (2018). Ameliorating the biological impacts of childhood adversity: a review of intervention programs. Child Abuse & Neglect, 81, 82-105.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). About adverse childhood experiences. Retrived from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/acestudy/aboutace.html

Chen, L. P., Murad, M. H., Paras, M. L., Colbenson, K. M., Sattler, A. L., Goranson, E. N., … & Zirakzadeh, A. (2010, July). Sexual abuse and lifetime diagnosis of psychiatric disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis. In Mayo Clinic Proceedings (Vol. 85, No. 7, pp. 618-629). Elsevier.

Cox, K. S., Sullivan, C. G., Olshansky, E., Czubaruk, K., Lacey, B., Scott, L., & Van Dijk, J. W. (2018). Critical conversation: Toxic stress in children living in poverty. Nursing Outlook, 66(2), 204-209.

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R.F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245-258. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

Finkelhorn, D., Hotaling, G., Lewis, I. A., & Smith, C. (1990). Sexual abuse in a national survey of adult men and women: Prevalence, characteristics, and risk factors. Child Abuse and Neglect, 14(1), 19-28.

Ford, K., Hughes, K., Hardcastle, K., Di Lemma, L. C., Davies, A. R., Edwards, S., & Bellis, M. A. (2019). The evidence base for routine enquiry into adverse childhood experiences: A scoping review. Child Abuse & Neglect, 91, 131-146.

Harvard University. (2019). Center on the developing child: Toxic stress. Retrieved from https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/toxic-stress/

Hillberg, T., Hamilton-Giachritsis, C., & Dixon, L. (2011). Review of meta-analyses on the association between child sexual abuse and adult mental health difficulties: A systematic approach. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 12(1), 38-49.

Irish, L., Kobayashi, I., & Delahanty, D. L. (2010). Long-term physical health consequences of childhood sexual abuse: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 35(5), 450-461.

Lacey, R. E., & Minnis, H. (2020). Practitioner Review: Twenty years of research with adverse childhood experience scores–Advantages, disadvantages and applications to practice. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 61(2), 116-130.

Merrick, M. T., Ford, D. C., Ports, K. A., & Guinn, A. S. (2018). Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences from the 2011- 2014 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System in 23 States. Early JAMA Pediatrics, 172(11), 1038-1044.

Middlebrooks, J. S., & Audage, N. C. (2008). The effects of childhood stress on health across the lifespan. (United States, Center for Disease Control, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control). Atlanta, GA.

Petruccelli, K., Davis, J., & Berman, T. (2019). Adverse childhood experiences and associated health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 97, 104127.

Sege, R. D., & Browne, C. H. (2017). Responding to ACEs with HOPE: Health outcomes from positive experiences. Academic Pediatrics, 17(7), S79-S85.

Society for Research in Child Development. (2018). The Science is clear: Separating families has long-term damaging psychological and health consequences for children, families, and communities. Retrieved from https://www.srcd.org/policy-media/statements-evidence

Steele, B.F. (1986). Notes on the lasting effects of early child abuse throughout the life cycle. Child Abuse & Neglect 10(3), 283-291.

United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2013). Child Maltreatment 2012. Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment.

United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2019). Child Maltreatment 2017. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/resource/child-maltreatment-2017

United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). What is child abuse or neglect? What is the definition of child abuse and neglect? Retrieved from https://www.hhs.gov/answers/programs-for-families-and-children/what-is-child-abuse/index.html

Valente, S. M. (2005). Sexual abuse of boys. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 18, 10–16. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6171.2005.00005.x

Walsh, D., McCartney, G., Smith, M., & Armour, G. (2019). Relationship between childhood socioeconomic position and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs): A systematic review. Journal Epidemiol Community Health, 73(12), 1087-1093.

OER Attribution:

“Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective, Second Edition” by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0 /modified and adapted by Ellen Skinner & Heather Brule, Portland State University

Introduction to Sociology 2e by Rice University is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 License. / modified and adapted by Ellen Skinner & Heather Brule, Portland State University

Additional written material by Ellen Skinner, Portland State University is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Media Attributions

- ACEs-consequences-large-compacthb2 © Center for Disease Control - Click for image reuse policy adapted by Authors of this textbook: made image more compact, adjusted color