Love and Relationships

Developmental Task of Early Adulthood: Intimacy vs. Isolation

Erikson’s (1950, 1968) sixth stage of psychosocial development focuses on establishing intimate relationships or risking social isolation. Intimate relationships are more difficult if one is still struggling with identity. Achieving a sense of identity is a life-long process, as there are periods of identity crisis and stability. Once a sense of identity is established, young adults' focus often turns to intimate relationships. The word "intimacy" is often used to describe romantic or sexual relationships, but it also refers to the closeness, caring, and personal disclosure that can be found in many other types of relationships as well-- and, of course, it is possible to have sexual relationships that do not include psychological intimacy or closeness. The need for intimacy can be met in many ways, including with friendships, familial relationships, and romantic relationships.

Friendships

Friendships provide one common way to achieve a sense of intimacy. In early adulthood, healthy friendships continue to be important for development, providing not only a source of support in tough times, but also improved self-esteem and general well-being (Berk, 2014; Collins & Madsen, 2006; Deci et al, 2006). As is the case in adolescence, friendships rich in intimacy, mutuality, and closeness are especially important for development (Blieszner & Roberto, 2012). Studies suggest that women’s friendships are characterized by somewhat more emotional intimacy in general, whereas men’s friendships tend to grow more emotionally close and include more personal disclosures the longer the friendships last (Berk, 2014; Sherman, de Vries, & Lansford, 2000). Friendships can tend to take a backseat when adults enter marriages and long-term partnerships, with more self-disclosures between romantic partners rather than between friends outside the partnership. At the same time, maintaining healthy friendships after marriage and the birth of children remains important for well-being (Berk, 2014; Birditt & Antonucci, 2007).

Workplace friendships. Friendships often take root in the workplace, since people spend as much, or more, time at work as they do with their family and friends (Kaufman & Hotchkiss, 2003). Often, it is through these relationships that people receive mentoring and obtain social support and resources, but they can also experience conflicts and the potential for misinterpretation when sexual attraction is an issue. Indeed, Elsesser and Peplau (2006) found that many workers reported that friendships grew out of collaborative work projects, and these friendships made their days more pleasant. In addition to those benefits, Riordan and Griffeth (1995) found that people who work in an environment where friendships can develop and be maintained are more likely to report higher levels of job satisfaction, job involvement, and organizational commitment, and they are more likely to remain in that job. Similarly, a Gallup poll revealed that employees who had “close friends” at work were almost 50% more satisfied with their jobs than those who did not (Armour, 2007).

Internet friendships. What influence does the Internet have on friendships? It is not surprising that people use the Internet with the goal of meeting and making new friends (Fehr, 2008; McKenna, 2008). Researchers have wondered whether virtual relationships (compared to ones conducted face-to-face) reduce the authenticity of relationships, or whether the Internet actually allows people to develop deep, meaningful connections. Interestingly, research has demonstrated that virtual relationships are often as intimate as in-person relationships; in fact, Bargh and colleagues found that online relationships are sometimes more intimate (Bargh et al., 2002). This can be especially true for those individuals who are socially anxious and lonely—such individuals are more likely to turn to the Internet to find new and meaningful relationships (McKenna, Green, & Gleason, 2002). McKenna et al. (2002) suggest that for people who have a hard time meeting and maintaining relationships, due to shyness, anxiety, or lack of face-to-face social skills, the Internet provides a safe, nonthreatening place to develop and maintain relationships. Similarly, Benford (2008) found that for high-functioning autistic individuals, the Internet facilitates communication and relationship development with others, which would be more difficult in face-to-face contexts, leading to the conclusion that Internet communication can be empowering for those who feel dissatisfied when communicating face to face.

Relationships with Parents and Siblings

In early adulthood the parent-child relationship transitions by necessity toward a relationship between two adults. This involves a reappraisal of the relationship by both parents and young adults. One of the biggest challenges for parents, especially during emerging adulthood, is coming to terms with the adult status of their children. Aquilino (2006) suggests that parents who are reluctant or unable to do so may hinder young adults’ identity development. This problem becomes more pronounced when young adults still reside with their parents and are financially dependent on them. Arnett (2004) reported that leaving home often helped promote psychological growth and independence in early adulthood.

Sibling relationships are one of the longest-lasting bonds in people’s lives. Yet, there is little research on the nature of sibling relationships in adulthood (Aquilino, 2006). What is known is that the nature of these relationships change, as adults have a choice as to whether they will create or maintain a close bond and continue to be a part of the life of a sibling. Siblings must make the same reappraisal of each other as adults, as parents have to with their adult children. Research has shown a decline in the frequency of interactions between siblings during early adulthood, as presumably peers, romantic relationships, and children become more central to the lives of young adults. Aquilino (2006) suggests that the task in early adulthood may be to maintain enough of a bond so that there will be a foundation for this relationship in later life. Those who are successful can often move away from the “older-younger” sibling conflicts of childhood, toward a more egalitarian relationship between two adults. Siblings that were close to each other in childhood are typically close in adulthood (Dunn, 1984, 2007), and in fact, it is unusual for siblings to develop closeness for the first time in adulthood. Overall, the majority of adult sibling relationships are close (Cicirelli, 2009).

Beginning Close Romantic Relationships: Factors influencing Attraction

Because most of us enter into a close romantic relationship at some point, it is useful to know what psychologists have learned about the principles of liking and loving. A major interest of psychologists is the study of interpersonal attraction, or what makes people like, and even love, each other.

Proximity. One important factor in initiating relationships is proximity, or the extent to which people are physically near us. Research has found that we are more likely to develop friendships with people who are nearby, for instance, those who live in the same dorm that we do, and even with people who just happen to sit nearer to us in our classes (Back, Schmukle, & Egloff, 2008).

Proximity has its effect on liking through the principle of mere exposure, which is the tendency to prefer stimuli (including, but not limited to people) that we have seen more frequently. The effect of mere exposure is powerful and occurs in a wide variety of situations. Infants tend to smile at a photograph of someone they have seen before more than they smile at a photograph of someone they are seeing for the first time (Brooks-Gunn & Lewis, 1981), and people prefer side-to-side reversed images of their own faces over their normal (nonreversed) face, whereas their friends prefer their normal face over the reversed one (Mita, Dermer, & Knight, 1977). This is expected on the basis of mere exposure, since people see their own faces primarily in mirrors, and thus are exposed to the reversed face more often.

Mere exposure may well have an evolutionary basis. We have an initial fear of the unknown, but as things become familiar, they seem more similar and safer, and thus produce more positive affect and seem less threatening and dangerous (Harmon-Jones & Allen, 2001; Freitas, Azizian, Travers, & Berry, 2005). When the stimuli are people, there may well be an added effect. Familiar people become more likely to be seen as part of the ingroup rather than the outgroup, and this may lead us to like them more. Zebrowitz and her colleagues found that we like people of our own race in part because they are perceived as similar to us (Zebrowitz, Bornstad, & Lee, 2007).

Similarity. An important determinant of attraction is a perceived similarity in values and beliefs between the partners (Davis & Rusbult, 2001). Similarity is important for relationships because it is more convenient if both partners like the same activities and because similarity supports one’s values. We can feel better about ourselves and our choice of activities if we see that our partner also enjoys doing the same things that we do. Having others like and believe in the same things we do makes us feel validated in our beliefs. This is referred to as consensual validation and is an important aspect of why we are attracted to others.

Self-Disclosure. Liking is also enhanced by self-disclosure, the tendency to communicate frequently, without fear of reprisal, and in an accepting and empathetic manner. Friends are friends because we can talk to them openly about our needs and goals and because they listen and respond to our needs (Reis & Aron, 2008). However, self-disclosure must be balanced. If we open up about our concerns that are important to us, we expect our partner to do the same in return. If the self-disclosure is not reciprocal, the relationship may not last.

Love

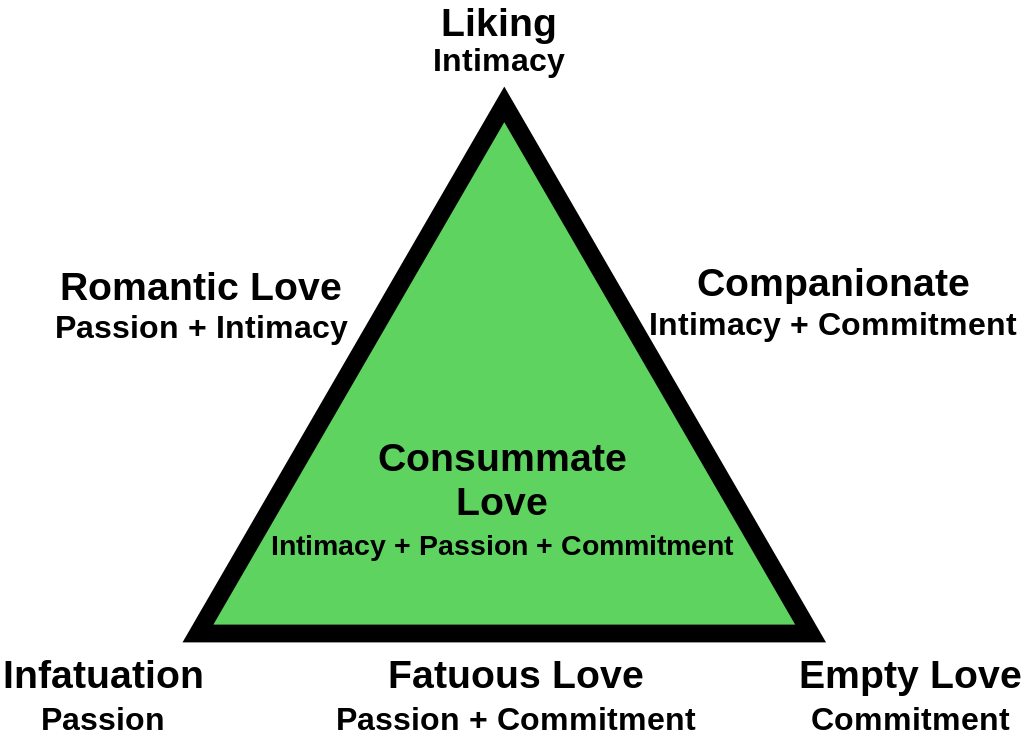

Philosophers and poets have wondered about the nature of love for centuries, and psychologists have also theorized about definitions, components, and kinds of love. Sternberg (1988) suggests that there are three main components of love: Passion, intimacy, and commitment (see figure, below). Love relationships vary depending on the presence or absence of each of these components. Passion refers to the intense, physical attraction partners feel toward one another. Intimacy involves the ability the share feelings, psychological closeness and personal thoughts with the other. Commitment is the conscious decision to stay together. Passion can be found in the early stages of a relationship, but intimacy takes time to develop because it is based on knowledge of and sharing with the partner. Once intimacy has been established, partners may resolve to stay in the relationship. Although many would agree that all three components are important to a relationship, many love relationships do not consist of all three. Let's look at other possibilities.

Liking. In this kind of relationship, intimacy or knowledge of the other and a sense of closeness is present. Passion and commitment, however, are not. Partners feel free to be themselves and disclose personal information. They may feel that the other person knows them well and can be honest with them and let them know if they think the person is wrong. These partners are friends. However, being told that your partner “thinks of you as a friend” can be a painful blow if you are attracted to them and seeking a romantic involvement.

Infatuation. Perhaps, this is Sternberg's version of "love at first sight" or what adolescents would call a "crush." Infatuation consists of an immediate, intense physical attraction to someone. A person who is infatuated finds it hard to think of anything but the other person. Brief encounters are played over and over in one's head; it may be difficult to eat and there may be a rather constant state of arousal. Infatuation is typically short-lived, however, lasting perhaps only a matter of months or as long as a year or so. It tends to be based on physical attraction and an image of what one “thinks” the other is all about.

Fatuous Love. However, some people who have a strong physical attraction push for commitment early in the relationship. Passion and commitment are aspects of fatuous love. There is no intimacy and the commitment is premature. Partners rarely talk seriously or share their ideas. They focus on their intense physical attraction and yet one, or both, is also talking of making a lasting commitment. Sometimes insistence on premature commitment follows from a sense of insecurity and a desire to make sure the partner is locked into the relationship.

Empty Love. This type of love may be found later in a relationship or in a relationship that was formed to meet needs other than intimacy or passion, including financial needs, childrearing assistance, or attaining/maintaining status. Here the partners are committed to staying in the relationship for the children, because of a religious conviction, or because there are no alternatives. However, they do not share ideas or feelings with each other and have no (or no longer any) physical attraction for one another.

Romantic Love. Intimacy and passion are components of romantic love, but there is no commitment. The partners spend much time with one another and enjoy their closeness, but have not made plans to continue. This may be true because they are not in a position to make such commitments or because they are looking for passion and closeness and are afraid it will die out if they commit to one another and start to focus on other kinds of obligations.

Companionate Love. Intimacy and commitment are the hallmarks of companionate love. Partners love and respect one-another and they are committed to staying together. However, their physical attraction may have never been strong or may have just died out over time. Nevertheless, partners are good friends and committed to one another.

Consummate Love. Intimacy, passion, and commitment are present in consummate love. This is often perceived by western cultures as “the ideal” type of love. The couple shares passion; the spark has not died, and the closeness is there. They feel like best friends, as well as lovers, and they are committed to staying together.

Attachment in Young Adulthood

Hazan and Shaver (1987) described the attachment styles of adults, using the same three general categories proposed by Ainsworth’s research on young children: secure, avoidant, and anxious/ambivalent. Hazan and Shaver developed three brief paragraphs describing the three adult attachment styles. Adults were then asked to think about romantic relationships they were in and select the paragraph that best described the way they felt, thought, and behaved in these relationships (See table, below).

Table 8.2 Attachment in Young Adulthood

| Which of the following best describes you in your romantic relationships? | |

|---|---|

| Attachment Style | Response |

| Secure | I find it relatively easy to get close to others and am comfortable depending on them and having them depend on me. I don’t often worry about being abandoned or about someone getting too close to me. |

| Avoidant | I am somewhat uncomfortable being close to others; I find it difficult to trust them completely, difficult to allow myself to depend on them. I am nervous when anyone gets too close, and often, love partners want me to be more intimate than I feel comfortable being. |

| Anxious/Resistant | I find that others are reluctant to get as close as I would like. I often worry that my partner doesn’t really love me or won’t stay with me. I want to merge completely with another person, and this sometimes scares people away. |

Adapted from Lally & Valentine-French, 2019 and Hazan & Shaver, 1987

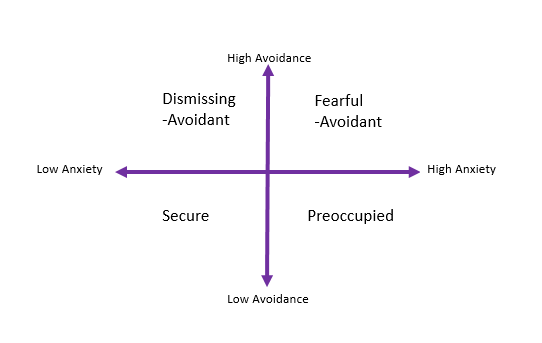

Bartholomew (1990) challenged the categorical view of attachment in adults and suggested that adult attachment was best described as varying along two dimensions; attachment related-anxiety and attachment-related avoidance. Attachment-related anxiety refers to the extent to which an adult worries about whether their partner really loves them. Those who score high on this dimension fear that their partner will reject or abandon them (Fraley, Hudson, Heffernan, & Segal, 2015). Attachment-related avoidance refers to whether an adult can open up to others, and whether they trust and feel they can depend on others. Those who score high on attachment-related avoidance are uncomfortable with opening up and may fear that such dependency may limit their sense of autonomy (Fraley et al., 2015). According to Bartholomew (1990) this would yield four possible attachment styles in adults; secure, dismissing, preoccupied, and fearful-avoidant (see Figure, below.)

Securely attached adults score lower on both dimensions. They are comfortable trusting their partners and do not worry excessively about their partner’s love for them. Adults with a dismissing style score low on attachment-related anxiety, but higher on attachment-related avoidance. Such adults dismiss the importance of relationships. They trust themselves, but do not trust others, thus do not share their dreams, goals, and fears with others. They do not depend on other people and feel uncomfortable when they have to do so.

Those with a preoccupied attachment are low in attachment-related avoidance, but high in attachment-related anxiety. Such adults are often prone to jealousy and worry that their partner does not love them as much as they need to be loved. Adults whose attachment style is fearful-avoidant score high on both attachment-related avoidance and attachment-related anxiety. These adults want close relationships, but do not feel comfortable getting emotionally close to others. They have trust issues with others and often do not trust their own social skills in maintaining relationships.

Research on attachment in adulthood has found that:

- Adults with insecure attachments report lower satisfaction in their relationships (Butzer, & Campbell, 2008; Holland, Fraley, & Roisman, 2012).

- Those high in attachment-related anxiety report more daily conflict in their relationships (Campbell, Simpson, Boldry, & Kashy, 2005).

- Those with avoidant attachment exhibit less support to their partners (Simpson, Rholes, Oriña, & Grich, 2002).

- Young adults show greater attachment-related anxiety than do middle-aged or older adults (Chopik, Edelstein, & Fraley, 2013).

- Some studies report that young adults show more attachment-related avoidance (Schindler, Fagundes, & Murdock, 2010), while other studies find that middle-aged adults show higher avoidance than younger or older adults (Chopik et al., 2013).

- Young adults with more secure and positive relationships with their parents make the transition to adulthood more easily than do those with more insecure attachments (Fraley, 2013).

- Young adults with secure attachments and authoritative parents were less likely to be depressed than those with authoritarian or permissive parents or who experienced an avoidant or ambivalent attachment (Ebrahimi, Amiri, Mohamadlou, & Rezapur, 2017).

Do people with certain attachment styles attract those with similar styles? When people are asked what kinds of psychological or behavioral qualities they are seeking in a romantic partner, a large majority of people indicate that they are seeking someone who is kind, caring, trustworthy, and understanding, that is, who has the kinds of attributes that characterize a “secure” caregiver (Chappell & Davis, 1998). However, we know that people do not always end up with others who meet their ideals. Are secure people more likely to end up with secure partners, and, vice versa, are insecure people more likely to end up with insecure partners? The majority of the research that has been conducted to date suggests that the answer is “yes.” Frazier, Byer, Fischer, Wright, and DeBord (1996) studied the attachment patterns of more than 83 heterosexual couples and found that, if the man was relatively secure, the woman was also likely to be secure.

One important question is whether these findings exist because (a) secure people are more likely to be attracted to other secure people, (b) secure people are likely to create security in their partners over time, or (c) some combination of these possibilities. Existing empirical research strongly supports the first alternative. For example, when people have the opportunity to interact with individuals who vary in security in a speed-dating context, they express a greater interest in those who are higher in security than those who are more insecure (McClure, Lydon, Baccus, & Baldwin, 2010). It also is likely that secure people, who have the characteristics that many consider make an ideal partner, have their choice of partners so they select ones who are also closer to the ideal, namely, secure people. However, there is also some evidence that people’s attachment styles mutually shape one another in close relationships. For example, in a longitudinal study, Hudson, Fraley, Vicary, and Brumbaugh (2012) found that, if one person in a relationship experienced a change in security, his or her partner was likely to experience a change in the same direction.

Do early experiences as children shape adult attachment? The majority of research on this issue is retrospective; that is, it relies on adults’ reports of what they recall about their childhood experiences. This kind of work suggests that secure adults are more likely to describe their early childhood experiences with their parents as being supportive, loving, and kind (Hazan & Shaver, 1987). A number of longitudinal studies are emerging that demonstrate prospective associations between early attachment experiences and adult attachment styles and/or interpersonal functioning in adulthood. For example, Fraley, Roisman, Booth- LaForce, Owen, and Holland (2013) found in a sample of more than 700 individuals studied from infancy to adulthood that maternal sensitivity across development prospectively predicted security at age 18. Simpson, Collins, Tran, and Haydon (2007) found that attachment security, assessed in infancy in the strange situation, predicted peer competence in grades one to three, which, in turn, predicted the quality of friendship relationships at age 16, which, in turn, predicted the expression of positive and negative emotions in their adult romantic relationships at ages 20 to 23. You can see how positive relationships with both parents and peers contribute to higher quality relationships with romantic partners.

It is easy to come away from such findings with the mistaken assumption that early experiences “determine” later outcomes. To be clear, attachment theorists assume that the connection between early experiences and subsequent outcomes is probabilistic, not deterministic. Having supportive and responsive experiences with caregivers early in life is assumed to set the stage for positive social development, but that does not mean that attachment patterns are set in stone. In short, even if an individual has far from optimal experiences in early life, attachment theory suggests that it is possible for that individual to develop well-functioning adult relationships. People are able to rework the effects of their early experiences through a number of corrective pathways, including relationships with siblings, other family members, teachers, and close friends. Security is best viewed as an accumulation of a person’s attachment history rather than a reflection of his or her early experiences alone. Those early experiences are considered important, not because they determine a person’s fate, but because they provide the foundation for subsequent experiences.

Relationships 101: Predictors of Marital Harmony

Advice on how to improve one’s marriage is centuries old. One of today’s experts on marital communication is John Gottman. Gottman (1999) differs from many marriage counselors in his belief that having a good marriage does not depend on compatibility. Rather, he argues that the way partners communicate with one another is crucial. At the University of Washington in Seattle, Gottman has conducted some of the most thorough and interesting studies of marital relationships. His research team measured the physiological responses of thousands of couples as they discuss issues of disagreement. Fidgeting in one’s chair, leaning closer to or further away from the partner while speaking, and increases in respiration and heart rate are all recorded and analyzed along with videotaped recordings of the partners’ exchanges. Gottman is trying to identify aspects of communication patterns that can accurately predict whether or not a couple will stay together. In marriages destined to fail, partners engage in the “marriage killers”: Contempt, criticism, defensiveness, and stonewalling. Each of these undermines the caring and respect that healthy marriages require. To some extent, all partnerships include some of these behaviors occasionally, but when these behaviors become the norm, they can signal that the end of the relationships is near; for that reason, they are known as "Gottman's Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse". Contempt, which it entails mocking or derision and communicates the other partner is inferior, is seen of the worst of the four because it is the strongest predictor of divorce. (Click here for a suggestions on diffusing your own contempt.)

Gottman, Carrere, Buehlman, Coan, and Ruckstuhl (2000) researched the perceptions newlyweds had about their partner and marriage. The Oral History Interview used in this study, which looks at eight variables in marriage including: Fondness/affection, we-ness, expansiveness/ expressiveness, negativity, disappointment, and three aspects of conflict resolution (chaos, volatility, glorifying the struggle), was able to predict the stability of the marriage (vs. divorce) with 87% accuracy at the four to six year-point and 81% accuracy at the seven to nine year-point. Gottman (1999) developed workshops for couples to strengthen their marriages based on the results of the Oral History Interview. Interventions include increasing positive regard for each other, strengthening their friendship, and improving communication and conflict resolution patterns.

Accumulated Positive Deposits to the "Emotional Bank Account." When there is a positive balance of relationship deposits this can help the overall relationship in times of conflict. For instance, some research indicates that a husband’s level of enthusiasm in everyday marital interactions was related to a wife’s affection in the midst of conflict (Driver & Gottman, 2004), showing that being friendly and making deposits can change the nature of conflict. Gottman and Levenson (1992) also found that couples rated as having more pleasant interactions, compared with couples with less pleasant interactions, reported higher marital satisfaction, less severe marital problems, better physical health, and less risk for divorce. Finally, Janicki, Kamarck, Shiffman, and Gwaltney (2006) showed that the intensity of conflict with a spouse predicted marital satisfaction, unless there was a record of positive partner interactions, in which case the conflict did not matter as much. Again, it seems as though having a positive balance through prior positive deposits helps to keep relationships strong even in the midst of conflict.

References

Aquilino, W. S. (2006). Family relationships and support systems in emerging adulthood. In J. J. Arnett & J. L. Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century (pp. 193-217). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Armour, S. (2007, August 2). Friendships and work: A good or bad partnership? USA Today. Retrieved from http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/money/workplace/2007-08-01-work-friends_N.htm

Back, M. D., Schmukle, S. C., & Egloff, B. (2008). Becoming friends by chance. Psychological Science, 19(5), 439–440.

Bargh, J. A., McKenna, K. Y. A, & Fitsimons, G. G. (2002). Can you see the real me? Activation and expression of the true self on the Internet. Journal of Social Issues, 58, 33–48.

Bartholomew, K. (1990). Avoidance of intimacy: An attachment perspective. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7, 147-178. DOI: 10.1037/0022-3524.61.2.226.

Benford, P. (2008). The use of Internet-based communication by people with autism (Doctoral dissertation, University of Nottingham).

Berk, Laura E. (2014). Exploring lifespan development (3rd ed.). Boston: Pearson.

Birditt, K. S., & Antonucci, T. C. (2007). Relationship quality profiles and well-being among married adults. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(4), 595.

Blieszner, R., & Roberto, K. A. (2012). Partners and friends in adulthood. In S. K. Whitbourne & M. J. Sliwinski (Eds.), Handbooks of developmental psychology. The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of adulthood and aging (p. 381–398). Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118392966.ch19

Brannan, D. & Mohr, C. D. (2020). Love, friendship, and social support. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/s54tmp7k

Brooks-Gunn, J., & Lewis, M. (1981). Infant social perception: Responses to pictures of parents and strangers. Developmental Psychology, 17(5), 647–649.

Butzer, B., & Campbell, L. (2008). Adult attachment, sexual satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction: A study of married couples. Personal Relationships, 15, 141-154.

Campbell, L., Simpson, J. A., Boldry, J., & Kashy, D. A. (2005). Perceptions of conflict and support in romantic relationships: The role of attachment anxiety. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 510-532.

Chappell, K. D., & Davis, K. E. (1998). Attachment, partner choice, and perception of romantic partners: An experimental test of the attachment-security hypothesis. Personal Relationships, 5, 327–342.

Chopik, W. J., Edelstein, R. S., & Fraley, R. C. (2013). From the cradle to the grave: Age differences in attachment from early adulthood to old age. Journal or Personality, 81 (2), 171-183 DOI: 10.1111/j. 1467-6494.2012.00793

Cicirelli, V. (2009). Sibling relationships, later life. In D. Carr (Ed.), Encyclopedia of the life course and human development. Boston, MA: Cengage.

Collins, W. A., & Madsen, S. D. (2006). Personal Relationships in Adolescence and Early Adulthood. In A. L. Vangelisti & D. Perlman (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of personal relationships (p. 191–209). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511606632.012

Davis, J. L., & Rusbult, C. E. (2001). Attitude alignment in close relationships. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 81(1), 65–84.

Deci, E. L., La Guardia, J. G., Moller, A. C., Scheiner, M. J., & Ryan, R. M. (2006). On the benefits of giving as well as receiving autonomy support: Mutuality in close friendships. Personality and social psychology bulletin, 32(3), 313-327.

Driver, J., & Gottman, J. (2004). Daily marital interactions and positive affect during marital conflict among newlywed couples. Family Process, 43, 301–314.

Dunn, J. (2007). Siblings and socialization. In J. E. Grusec & P. D. Hastings (Eds.), Handbook of socialization. New York: Guilford.

Ebrahimi, L., Amiri, M., Mohamadlou, M., & Rezapur, R. (2017). Attachment styles, parenting styles, and depression. International Journal of Mental Health, 15, 1064-1068.

Elsesser, L., & Peplau, L. A. (2006). The glass partition: Obstacles to cross-sex friendships at work. Human Relations, 59(8), 1077–1100.

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. New York: Norton.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton.

Fehr, B. (2008). Friendship formation. In S. Sprecher, A. Wenzel, & J. Harvey (Eds.), Handbook of Relationship Initiation (pp. 29–54). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Fraley, R. C., Hudson, N. W., Heffernan, M. E., & Segal, N. (2015). Are adult attachment styles categorical or dimensional? A taxometric analysis of general and relationship-specific attachment orientations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109 (2), 354-368.

Fraley, R. C., Roisman, G. I., Booth-LaForce, C., Owen, M. T., & Holland, A. S. (2013). Interpersonal and genetic origins of adult attachment styles: A longitudinal study from infancy to early adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104, 8817-838.

Frazier, P. A, Byer, A. L., Fischer, A. R., Wright, D. M., & DeBord, K. A. (1996). Adult attachment style and partner choice: Correlational and experimental findings. Personal Relationships, 3, 117–136.

Freitas, A. L., Azizian, A., Travers, S., & Berry, S. A. (2005). The evaluative connotation of processing fluency: Inherently positive or moderated by motivational context? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41(6), 636–644.

Gottman, J. M. (1999). Couple's handbook: Marriage Survival Kit Couple's Workshop. Seattle, WA: Gottman Institute.

Gottman, J. M., & Levenson, R. W. (1992). Marital processes predictive of later dissolution: Behavior, physiology and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 221–233.

Gottman, J. M., Carrere, S., Buehlman, K. T., Coan, J. A., & Ruckstuhl, L. (2000). Predicting marital stability and divorce in newlywed couples. Journal of Family Psychology, 14(1), 42-58.

Harmon-Jones, E., & Allen, J. J. B. (2001). The role of affect in the mere exposure effect: Evidence from psychophysiological and individual differences approaches. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(7), 889–898.

Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52 (3), 511-524.

Hendrick, C., & Hendrick, S. S. (Eds.). (2000). Close relationships: A sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Holland, A. S., Fraley, R. C., & Roisman, G. I. (2012). Attachment styles in dating couples: Predicting relationship functioning over time. Personal Relationships, 19, 234-246. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2011.01350.x

Hudson, N. W., Fraley, R. C., Vicary, A. M., & Brumbaugh, C. C. (2012). Attachment coregulation: A longitudinal investigation of the coordination in romantic partners’ attachment styles. Manuscript under review.

Janicki, D., Kamarck, T., Shiffman, S., & Gwaltney, C. (2006). Application of ecological momentary assessment to the study of marital adjustment and social interactions during daily life. Journal of Family Psychology, 20, 168–172.

Kaufman, B. E., & Hotchkiss, J. L. 2003. The economics of labor markets (6th ed.). Mason, OH: Thomson South-Western.

McClure, M. J., Lydon., J. E., Baccus, J., & Baldwin, M. W. (2010). A signal detection analysis of the anxiously attached at speed-dating: Being unpopular is only the first part of the problem. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36, 1024–1036.

McKenna, K. A. (2008) MySpace or your place: Relationship initiation and development in the wired and wireless world. In S. Sprecher, A. Wenzel, & J. Harvey (Eds.), Handbook of relationship initiation (pp. 235–247). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

McKenna, K. Y. A., Green, A. S., & Gleason, M. E. J. (2002). Relationship formation on the Internet: What’s the big attraction? Journal of Social Issues, 58, 9–31.

Mita, T. H., Dermer, M., & Knight, J. (1977). Reversed facial images and the mere-exposure hypothesis. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 35(8), 597–601.

Reis, H. T., & Aron, A. (2008). Love: What is it, why does it matter, and how does it operate? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(1), 80–86.

Riordan, C. M., & Griffeth, R. W. (1995). The opportunity for friendship in the workplace: An underexplored construct. Journal of Business and Psychology, 10, 141–154.

Schindler, I., Fagundes, C. P., & Murdock, K. W. (2010). Predictors of romantic relationship formation: Attachment style, prior relationships, and dating goals. Personal Relationships, 17, 97-105.

Sherman, A. M., De Vries, B., & Lansford, J. E. (2000). Friendship in childhood and adulthood: Lessons across the life span. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 51(1), 31-51.

Simpson, J. A., Collins, W. A., Tran, S., & Haydon, K. C. (2007). Attachment and the experience and expression of emotions in adult romantic relationships: A developmental perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 355–367.

Simpson, J. A., Rholes, W. S., Oriña, M. M., & Grich, J. (2002). Working models of attachment, support giving, and support seeking in a stressful situation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 598-608.

Sternberg, R. (1988). A triangular theory of love. New York: Basic.

Tannen, D. (1990). You just don't understand: Women and men in conversation. New York: Morrow.

Zebrowitz, L. A., Bronstad, P. M., & Lee, H. K. (2007). The contribution of face familiarity to in group favoritism and stereotyping. Social Cognition, 25(2), 306–338.

OER Attribution:

"Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective, Second Edition" by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0

Love, Friendship, and Social Support by Debi Brannan and Cynthia D. Mohr is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Additional written material by Ellen Skinner & Heather Brule, Portland State University is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Media Attributions

- 1024px-Triangular_Theory_of_Love.svg © Lnesa is licensed under a Public Domain license

- four category model is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license