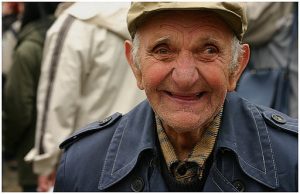

Late Adulthood

Late adulthood spans the time when we reach our mid-sixties until death. This is the longest developmental stage across the lifespan. In this chapter, we will consider the growth in numbers for those in late adulthood, how that number is expected to change in the future, and the consequences this will have for both the United States and the world. We will also examine several theories of human aging, the physical, cognitive, and socioemotional changes that occur with this population, and the vast diversity among those in this developmental stage. Further, ageism and many of the myths associated with those in late adulthood will be explored.

Late Adulthood in America

Late adulthood, which includes those aged 65 years and above, is the fastest growing age division of the United States population (Gatz, Smyer, & DiGilio, 2016). Currently, one in seven Americans is 65 years of age or older. The first of the baby boomers (born from 1946-1964) turned 65 in 2011, and approximately 10,000 baby boomers turn 65 every day. By the year 2050, almost one in four Americans will be over 65, and will be expected to live longer than previous generations. According to the U. S. Census Bureau (2014b) a person who turned 65 in 2015 can expect to live another 19 years, which is 5.5 years longer than someone who turned 65 in 1950. This increasingly aged population has been referred to as the “graying of America”. This “graying” is already having significant effects on the nation in many areas, including work, health care, housing, social security, caregiving, and adaptive technologies. Table 10.1 shows the 2012, 2020, and 2030 projected percentages of the U.S. population ages 65 and older.

Table 10.1 Percent of United States Population 65 Years and Older

| Percent of United States Population | 2012 | 2020 | 2030 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 65 Years and Older | 13.7% | 16.8% | 20.3% |

| 65-69 | 4.5% | 5.4% | 5.6% |

| 70-74 | 3.2% | 4.4% | 5.2% |

| 75-79 | 2.4% | 3.0% | 4.1% |

| 80-84 | 1.8% | 1.9% | 2.9% |

| 85 Years and Older | 1.9% | 2.0% | 2.5% |

adapted from Lally & Valentine-French (2019) and compiled from data from An Aging Nation: The older population in the United States. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/p25-1140.pdf

The “Graying” of the World

Even though the United States is aging, it is still younger than most other developed countries (Ortman, Velkoff, & Hogan, 2014). Germany, Italy, and Japan all had at least 20% of their population aged 65 and over in 2012, and Japan had the highest percentage of elderly. Additionally, between 2012 and 2050, the proportion aged 65 and over is projected to increase in all developed countries. Japan is projected to continue to have the oldest population in 2030 and 2050. Table 10.2 shows the percentages of citizens aged 65 and older in select developed countries in 2012 and projected for 2030 and 2050.

Table 10.2 Percentage of Citizens 65 Years and Older in Six Developed Countries

| Percent of Population 65 and Older | 2012 | 2030 | 2050 |

|---|---|---|---|

| America | 13.7% | 20.3% | 22% |

| Japan | 24% | 32.2% | 40% |

| Germany | 20% | 27.9% | 30% |

| Italy | 20% | 25.5% | 31% |

| Canada | 16.5% | 25% | 26.5% |

| Russia | 13% | 20% | 26% |

adapted from Lally & Valentine-French (2019) and compiled from data from An Aging Nation: The older population in the United States. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/p25-1140.pdf

According to the National Institute on Aging (NIA, 2015b), there are 524 million people over 65 worldwide. This number is expected to increase from 8% to 16% of the global population by 2050. Between 2010 and 2050, the number of older people in less developed countries is projected to increase more than 250%, compared with only a 71% increase in developed countries. Declines in fertility and improvements in longevity account for the percentage increase for those 65 years and older. In more developed countries, fertility fell below the replacement rate of two live births per woman by the 1970s, down from nearly three children per woman around 1950. Fertility rates also fell in many less developed countries from an average of six children in 1950 to an average of two or three children in 2005. In 2006, fertility was at or below the two-child replacement level in 44 less developed countries (NIA, 2015d).

In total number, the United States is projected to have a larger older population than the other developed nations, but a smaller older population compared with China and India, the world’s two most populous nations (Ortman et al., 2014). By 2050, China’s older population is projected to grow larger than the total U.S. population today. As the population ages, concerns grow about who will provide for those requiring long-term care. In 2000, there were about 10 people 85 and older for every 100 persons between ages 50 and 64. These midlife adults are the most likely care providers for their aging parents. The number of old requiring support from their children is expected to more than double by the year 2040 (He, Sengupta, Velkoff, & DeBarros, 2005). These families will certainly need external physical, emotional, and financial support in meeting this challenge.

Age Periods during Late Adulthood

Late adulthood encompasses a long period, from age 60 potentially to age 120– sixty years! Researchers recognize that within that time period, from age 60 until death, there are multiple ages or sub-periods, that can be distinguished based on differences in peoples’ typical physical health and mental functioning during those age periods. In this chapter, we will be dividing the stage into four age periods: Young–old (60-74), old-old (75-84), the oldest-old (85-99), and centenarians (100+). These categories are based on the conceptions of aging including, biological, psychological, social, and chronological differences. They also reflect the increase in longevity of those living to this latter stage.

Young-old (60-74). Generally, this age span includes many positive aspects and is considered the “golden years” of adulthood. When compared to those who are older, the young-old experience relatively good health and social engagement (Smith, 2000), knowledge and expertise (Singer, Verhaeghen, Ghisletta, Lindenberger, & Baltes, 2003), and adaptive flexibility in daily living (Riediger, Freund, & Baltes, 2005). The young-old also show strong performance in attention, memory, and crystallized intelligence. In fact, those identified as young-old are more similar to those in midlife. This group is less likely to require long-term care, to be dependent or poor, and more likely to be married, working for pleasure rather than income, and living independently. Overall, those in this age period feel a sense of happiness and emotional well-being that is better than at any other period of adulthood (Carstensen, Fung, & Charles, 2003; George, 2009; Robins & Trzesniewski, 2005). It is also an unusual age in that people are considered both in old age and not in old age (Rubinstein, 2002).

Old-old (75-84). Adults in this age period are likely to be living independently, but often experience physical impairments since chronic diseases increase after age 75. For example, congestive heart failure is 10 times more common in people 75 and older, than in younger adults (National Library of Medicine, 2019). In fact, half of all cases of heart failure occur in people after age 75 (Strait & Lakatta, 2012). In addition, hypertension and cancer rates are also more common after 75, but because they are linked to lifestyle choices, they typically can be can prevented, lessoned, or managed (Barnes, 2011b).

Oldest-old (85-99). Among the older adult population. this age group often includes people who have more serious chronic ailments. In the U.S., the oldest-old represented 14% of the older adult population in 2015 (He, Goodkind, & Kowal, 2016). This age group is one of the fastest growing worldwide and is projected to increase more than 300% over its current levels (NIA, 2015b). It is projected that there will be nearly 18 million in oldest-old age group by 2050, or about 4.5% of the U. S. population, compared with less than 2% of the population today. Females comprise more than 60% of those 85 and older, but they also suffer from more chronic illnesses and disabilities than older males (Gatz et al., 2016).

While this age group accounts for only 2% of the U. S. population, it accounts for 9% of all hospitalizations (Levant, Chari & DeFrances, 2015). In a study of over 64,000 patients age 65 and older who visited an emergency department, the admission rates increased with age. Thirty-five percent of admissions after an emergency room visit were the young old, almost 43% were the old-old, and nearly half were the oldest-old (Lee, Oh, Park, Choi, & Wee, 2018). The most common reasons for hospitalization for the oldest-old were congestive heart failure, pneumonia, urinary tract infections, septicemia, stroke, and hip fractures. In recent years, hospitalizations for many of these medical problems have been reduced. However, hospitalization for urinary tract infections and septicemia has increased for those 85 and older Levant et al., 2015). The mortality rate was also higher with age.

Those 85 and older are more likely to require long-term care and to be in nursing homes than the youngest-old. Almost 50% of the oldest-old require some assistance with daily living activities (APA, 2016). However, most still live in the community rather than a nursing home (Stepler, 2016b). The oldest-old are less likely to be married and living with a spouse compared with the majority of the young-old (APA, 2016; Stepler, 2016c). Gender is also an important factor in the likelihood of being married or living with one’s spouse.

Centenarians (100+). A segment of the oldest-old are centenarians, that is, 100 or older, and some are also referred to as supercentarians, those 110 and older (Wilcox, Wilcox & Ferrucci, 2008). In 2015 there were nearly half a million centenarians worldwide, and it is estimated that this age group will grow to almost 3.7 million by 2050. The U. S. has the most centenarians, but Japan and Italy have the most per capita (Stepler, 2016e). Most centenarians tended to be healthier than many of their peers as they were growing older, and often there was a delay in the onset of any serious disease or disability until their 90s. Additionally, 25% reached 100 with no serious chronic illnesses, such as depression, osteoporosis, heart disease, respiratory illness, or dementia (Ash et al. 2015). Centenarians are more likely to experience a rapid terminal decline in later life, meaning that for most of their adulthood, and even older adult years, they are relatively healthy in comparison to many other older adults (Ash et al., 2015; Wilcox et al., 2008). According to Guinness World Records (2016), Jeanne Louise Calment has been documented to be the longest living person at 122 years and 164 days old (See Figure 10.2).

Psychosocial Development during Late Adulthood

Developmental Task of Late Adulthood: Integrity vs. Despair

Erikson framed the last part of the lifespan with the developmental task of Integrity versus Despair. In terms of psychosocial development, the tasks of adulthood were about becoming the self that you want to become (i.e., Identity) and creating the life you want to live, including establishing or maintaining the close interpersonal relationships that will be crucial to your physical and psychological health and well -being (i.e., Intimacy). The value of that life project is negotiated during middle adulthood in the search for meaning and a purpose larger than yourself that will contribute to your legacy (i.e., Generativity). So in old age, this final task basically comes down to whether you have built a life and constructed a self that is sufficient to withstand the disintegration of your physical body, the death of many of those you love, and eventually and inevitably, strong enough to face your own impending death with dignity and grace.

Like all psychosocial tasks, this one has two potential resolutions: Integrity, or a sense of self-acceptance, contentment with life and imminent death versus Despair, or a lack of fulfillment or peace and the inability to come to terms with life, aging, and approaching death. Development during elderhood, as during all developmental periods, is a bio-psycho-social process that takes place in specific societal and historical contexts. But this task, at the end of life, offers offers us the prospect of lifting off of those geographical, societal, and temporal limitations. We have the potential to transcend them, to establish a sense of wholeness and acceptance by getting in touch with our universal connection to humanity, past, present, and future. Like birth, death is a journey that every single one of us will take.

Erikson’s Ninth Stage of Psychosocial Development

Erikson collaborated with his wife, Joan, throughout much of his work on psychosocial development. In the Eriksons’ older years, they re-examined the eight stages and generated additional ideas about how development evolves during a person’s 80s and 90s. After Erik Erikson passed away in 1994, Joan published a chapter on the ninth stage of development, in which she proposed (from her own experiences and Erikson’s notes) that older adults revisit the previous eight stages and deal with the previous conflicts in new ways, as they cope with the physical and social changes of growing old. In the first eight stages, all of the conflicts are presented in a syntonic-dystonic matter, meaning that the first term listed in the conflict is the positive, sought-after achievement and the second term is the less-desirable goal (i.e., trust is more desirable than mistrust and integrity is more desirable than despair) (Perry et al., 2015).

During the ninth stage, the Erikson’s argue that the dystonic, or less desirable outcome, come to take precedence again. For example, an older adult may become mistrustful (trust vs. mistrust), feel more guilt about not having the abilities to do what they once did (initiative vs. guilt), feel less competent compared with others (industry vs. inferiority), lose a sense of identity as they become dependent on others (identity vs. role confusion), become increasingly isolated (intimacy vs. isolation), and feel that they have less to offer society (generativity vs. stagnation) (Gusky, 2012). The Eriksons found that those who successfully come to terms with these changes and adjustments in later life make headway towards gerotranscendence, a term coined by gerontologist Lars Tornstam to represent a greater awareness of one’s own life and connection to the universe, increased ties to the past, and a positive, transcendent, perspective about life.

Theories of Successful Aging

Psychologists and sociologist have long wondered how people manage to age successfully, and many theories have been put developed that highlight the keys to successful aging. We examine five: (1) Activity theory; (2) Continuity theory; (3) Socioemotional selectivity theory; (4) Selective optimization with compensation; and (5) Developmental self-regulation theory.

- Developed by Havighurst and Albrecht in 1953, activity theory addresses the issue of how persons can best adjust to the changing circumstances of old age–e.g., retirement, illness, loss of friends and loved ones through death, and so on. In addressing this issue, they recommend that older adults involve themselves in voluntary and leisure organizations, child care and other forms of social interaction. Activity theory thus strongly supports the avoidance of a sedentary lifestyle and considers it essential to health and happiness that the older person remains active physically and socially. In other words, the more active older adults are the more stable and positive their self-concept will be, which will then lead to greater life satisfaction and higher morale (Havighurst & Albrecht, 1953). Activity theory suggests that many people are barred from meaningful experiences as they age, but older adults who continue find ways to remain active can work toward replacing lost opportunities with new ones (Nilsson et al., 2015).

- Continuity theory suggests as people age, they continue to view the self in much the same way as they did when they were younger. An older person’s approach to problems, goals, and situations is much the same as it was when they were younger. They are the same individuals, but simply in older bodies. Consequently, older adults continue to maintain their identity even as they give up previous roles. For example, a retired Coast Guard commander attends reunions with shipmates, stays interested in new technology for home use, is meticulous in the jobs he does for friends or at church, and displays mementos from his experiences on the ship. He is able to maintain a sense of self as a result. People do not give up who they are as they age. Hopefully, they are able to share these aspects of their identity with others throughout life. Focusing on what a person is still able to do and pursuing those interests and activities is one way to optimize and maintain self-identity.

- The Socioemotional Selectivity Theory focuses on changes in motivation for actively seeking social contact with others (Carstensen, 1993; Carstensen, Isaacowitz & Charles, 1999). This theory proposes that with increasing age, our motivational goals change based on how much time we have left to live. Rather than focusing on acquiring information from many diverse social relationships, as adolescents and young adults tend to do, older adults focus on the emotional aspects of relationships. To optimize the experience of positive affect, older adults actively restrict their social life to prioritize time spent with emotionally close significant others. In line with this theory, older marriages are found to be characterized by enhanced positive and reduced negative interactions and older partners show more affectionate behavior during conflict discussions than do middle-aged partners (Carstensen, Gottman, & Levenson, 1995). Research showing that older adults have smaller networks compared to young adults, and tend to avoid negative interactions, also supports this theory.

- Selective Optimization with Compensation is a strategy for improving health and well being in older adults and a model for successful aging. It is recommended that seniors select and optimize their best abilities and most intact functions while compensating for declines and losses. This means, for example, that a person who can no longer drive, is able to find alternative transportation, or a person who is compensating for having less energy, learns how to reorganize the daily routine to avoid over-exertion. Perhaps nurses and other allied health professionals working with this population will begin to focus more on helping patients remain independent by optimizing their best functions and abilities rather than simply treating illnesses. Promoting health and independence are essential for successful aging.

- Developmental Self-regulation Theory is a dual-process model that could have been based on St. Augustine’s serenity prayer. On the one hand, is primary control, or the strength and courage to take action to change the things that can be changed. This includes a sense of self-efficacy to take action needed to make lifestyle changes or undergo treatments that optimize functioning, such as a healthy diet, exercise, medical treatments (like taking one’s insulin or cataract surgery), or adopting outside aids like a cane or walker. The second process is called accommodation, and it involves the grace to accept the things that cannot be changed. This attitude of willing acceptance includes understanding, gratitude for times past, and a focus on the positive things that still remain. Such accommodation can be contrasted with furious resentment or depressed resignation to the losses of aging. In fact, some researchers argue that depression in old age is often due, not to the losses of control aging inevitably entails, but from an inability to accommodate, that is, to relinquish activities and goals that are no longer feasible.

Generativity in Late Adulthood

People in late adulthood continue to be productive in many ways. These include work, education, volunteering, family life, and intimate relationships. Older adults also experience generativity (recall Erikson’s previous stage of generativity vs. stagnation) through voting, forming and helping social institutions like community centers, churches and schools. Thinking of the issue of legacy, psychoanalyst Erik Erikson wrote “I am what survives me” (Havey, 2015).

Productivity in Work

Some older people continue to be productive in work. Mandatory retirement is now illegal in the United States. However, many do choose retirement by age 65. Most people leave work by choice, and the primary factors that influence decisions about when to retire are health status, finances, and satisfaction at work. Those who do leave by choice adjust to retirement more easily. Chances are, they have prepared for a smoother transition by gradually giving more attention to an avocation or interest as they approach retirement. And they are more likely to be financially ready to retire. Those who must leave abruptly for health reasons or because of layoffs or downsizing have a more difficult time adjusting to their new circumstances. Men, especially, can find unexpected retirement difficult.

Women may feel less of an identify loss after retirement because much of their identity may have come from family roles as well. At the same time, however, women tend to have poorer retirement funds accumulated from work and if they take their retirement funds in a lump sum (be that from their own or from a deceased husband’s funds), are more at risk of outliving those funds. Because they will on average live longer, women need better financial planning in retirement. Sixteen percent of adults over 65 were in the labor force in 2008 (U. S. Census Bureau 2011). Globally, 6.2% are in the labor force and this number is expected to reach 10.1 million by 2016. Many adults 65 and older continue to work either full-time or part-time either for income or pleasure or both. In 2003, 39% of full-time workers over 55 were women over the age of 70; 53% were men over 70. This increase in numbers of older adults is likely to mean that more will continue to part of the workforce in years to come (He, et al., 2005).

Volunteering: Face-to-face and Virtually

About 40% of older adults are involved in some type of structured, face-to-face, volunteer work. But many older adults, about 60%, engage in a sort of informal type of volunteerism, helping out neighbors or friends rather than working in an organization (Berger, 2005). They may help a friend by taking them somewhere or shopping for them, etc. Some do participate in organized volunteer programs but interestingly enough, those who do tend to work part-time as well. Those who retire and do not work are less likely to feel that they have a contribution to make. (It’s as if when one gets used to staying at home, one’s confidence to go out into the world diminishes.) And those who have recently retired are more likely to volunteer than those over 75 years of age. New opportunities exist for older adults to serve as virtual volunteers by dialoguing online with others from around their world and sharing their support, interests, and expertise. According to an article from the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP), virtual volunteerism has increased from 3,000 participants in 1998 to over 40,000 in 2005. These volunteer opportunities range from helping teens with their writing to communicating with ‘neighbors’ in villages in developing countries. Virtual volunteering is available to those who cannot engage in face-to-face interactions and opens up a new world of possibilities and ways to connect, maintain identity, and be productive (Uscher, 2006).

Relationship with Adult Children

Many older adults provide financial assistance and/or housing to adult children. at this point in history, there is more support going from the older parent to the younger adult children than in the other direction (Fingerman & Birditt, 2011). In addition to providing for their own children, many elders are raising their grandchildren. Consistent with socioemotional selectivity theory, older adults seek, and are helped by, their adult children providing emotional support (Lang & Schütze, 2002). Lang and Schütze, as part of the Berlin Aging Study (BASE), surveyed adult children (mean age 54) and their aging parents (mean age 84). They found that the adult children of older parents who provided emotional support, such as showing tenderness toward their parent, cheering the parent up when he or she was sad, tended to report greater life satisfaction. In contrast, older adults whose children provided informational support, such as providing advice to the parent, reported less life satisfaction. Lang and Schütze found that older adults wanted their relationship with their children to be more emotionally meaningful, but they did not want their children telling them what to do. Daughters and adult children who were younger, tended to provide such support more than sons and adult children who were older. Lang and Schütze also found that adult children who were more autonomous rather than emotionally dependent on their parents, had more emotionally meaningful relationships with their parents, from both the parents’ and adult children’s point of view.

Friendships

Friendships are not formed in order to enhance status or careers, and may be based purely on a sense of connection or the enjoyment of being together. Most elderly people have at least one close friend. These friends may provide emotional as well as physical support. Being able to talk with friends and rely on others is very important during this stage of life. Bookwala, Marshall, and Manning (2014) found that the availability of a friend played a significant role in protecting women’s health from the impact of widowhood. Specifically, those who became widowed and had a friend as a confidante, reported significantly lower somatic depressive symptoms, better self-rated health, and fewer sick days in bed than those who reported not having a friend as a confidante. In contrast, having a family member as a confidante did not provide health protection for those recently widowed.

Education

Twenty percent of people over 65 have a bachelors or higher degree. And over 7 million people over 65 take adult education courses (U. S. Census Bureau, 2011). Enriching experiences of lifelong learning are offered through continuing education programs on college campuses or programs known as “Elderhostels” which allow older adults to travel abroad, live on campus, and study. Academic courses as well as practical skills such as computer classes, foreign languages, budgeting, and holistic medicines are among the courses offered. Older adults who have higher levels of education are more likely to take continuing education. But offering more educational experiences to a diverse group of older adults, including those who are institutionalized in nursing homes, can enhance elder students’ quality of life.

Religious Activities

People tend to become more involved in prayer and religious activities as they age. This provides a social network as well as a belief system which can combat the fear of death. Religious activities provide a focus for volunteerism and other activities as well. For example, one elderly woman prides herself on knitting prayer shawls that are given to those who are sick. Another serves on the alter guild and is responsible for keeping robes and linens clean and ready for communion.

Political Activism

The elderly are very politically active. They have high rates of voting and engage in letter writing to congress on issues that not only affect them, but on a wide range of domestic and foreign concerns. In the past three presidential elections, over 70 percent of people 65 and older showed up at the polls to vote (U. S. Census Bureau, 2011).

Loneliness or Solitude

Loneliness is the discrepancy between the social contact a person has and the contacts a person wants (Brehm, Miller, Perlman, & Campbell, 2002). It can result from social or emotional isolation. Women tend to experience loneliness due to social isolation; men from emotional isolation. Loneliness can be accompanied by a lack of self-worth, impatience, desperation, and depression. Being alone does not always result in loneliness. For some, being alone means solitude. Solitude involves gaining self-awareness, taking care of the self, being comfortable alone, and pursuing one’s interests (Brehm et al., 2002). In contrast, loneliness is perceived social isolation.

For those in late adulthood, loneliness can be especially detrimental. Novotney (2019) reviewed the research on loneliness and social isolation and found that loneliness was linked to a 40% increase in the risk for dementia and a 30% increase in the risk of stroke or coronary heart disease. This was hypothesized to be due to reasons that were both biological (e.g., a rise in stress hormones), psychological (e.g., depression and anxiety), as well as social (e.g., the individual lacks encouragement from others to engage in healthy behaviors). In contrast, older adults who take part in social clubs and church groups have a lower risk of death. Opportunities to reside in mixed age housing and continuing to feel like a productive member of society have also been found to decrease feelings of social isolation, and thus loneliness.

Late Adult Lifestyles

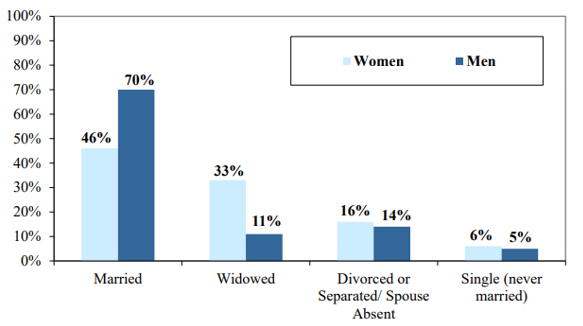

Marriage. As can be seen in Figure 10.4, the most common living arrangement for older adults in 2017 was marriage (AOA, 2017). This status was more common for older men than for older women, who based on differences in average life expectancy, typically outlive their husbands.

Divorce. As noted previously, older adults are divorcing at higher rates than in prior generations. However, adults age 65 and over are still less likely to divorce than middle-aged and young adults (Wu & Schimmele, 2007). Divorce poses a number of challenges for older adults, especially women, who are more likely to experience financial difficulties and are more likely to remain single than are older men (McDonald & Robb, 2004). However, in both America (Lin, 2008) and England (Glaser, Stuchbury, Tomassini, & Askham, 2008), studies have found that the adult children of divorcing parents offer more support and care to their mothers than their fathers. While divorced, older men may be better off financially and are more likely to find another partner, so they may receive less support from their adult children.

Dating. Due to changing social norms and shifting cohort demographics, it has become more common for single older adults to be involved in dating and romantic relationships (Alterovitz & Mendelsohn, 2011). An analysis of widows and widowers ages 65 and older found that 18 months after the death of a spouse, 37% of men and 15% of women were interested in dating (Carr, 2004a). Unfortunately, opportunities to develop close relationships often diminish in later life as social networks decrease because of retirement, relocation, and the death of friends and loved ones (de Vries, 1996). Consequently, older adults, much like those younger, are increasing their social networks using technologies, including e-mail, chat rooms, and online dating sites (Fox, 2004; Wright & Query, 2004; Papernow, 2018).

Interestingly, older men and women parallel online dating information as those younger. Alterovitz and Mendelsohn (2011) analyzed 600 internet personal ads from different age groups, and across the life span, men sought physical attractiveness and offered status-related information more than women. With advanced age, men desired women increasingly younger than themselves, whereas women desired older men until ages 75 and over, when they sought men younger than themselves. Research has previously shown that older women in romantic relationships are not interested in becoming a caregiver or becoming widowed for a second time (Carr, 2004a).

Additionally, older men are more eager to repartner than are older women (Davidson, 2001; Erber & Szuchman, 2015). Concerns expressed by older women included not wanting to lose their autonomy, care for a potentially ill partner, or merge their finances with someone (Watson & Stelle, 2011). Older dating adults also need to know about threats to sexual health, including being at risk for sexually transmitted diseases, including chlamydia, genital herpes, and HIV. Nearly 25% of people living with HIV/AIDS in the United States are 50 or older (Office on Women’s Health, 2010b). Githens and Abramsohn (2010) found that only 25% of adults 50 and over who were single or had a new sexual partner used a condom the last time they had sex. Robin (2010) stated that 40% of those 50 and over have never been tested for HIV. These results indicate that educating all individuals, not just adolescents, on healthy sexual behavior is important.

Remarriage and Cohabitation. Older adults who remarry often find that their remarriages are more stable than those of younger adults. Kemp and Kemp (2002) suggest that greater emotional maturity may lead to more realistic expectations regarding marital relationships, leading to greater stability in remarriages in later life. Older adults are also more likely to be seeking companionship in their romantic relationships. Carr (2004a) found that older adults who have considerable emotional support from their friends were less likely to seek romantic relationships. In addition, older adults who have divorced often desire the companionship of intimate relationships without marriage. As a result, cohabitation is increasing among older adults, and like remarriage, cohabitation in later adulthood is often associated with more positive consequences than it is in younger age groups (King & Scott, 2005). No longer being interested in raising children, and perhaps wishing to protect family wealth, older adults may see cohabitation as a good alternative to marriage. In 2014, 2% of adults age 65 and up were cohabitating (Stepler, 2016b).

Living Apart Together. In addition to cohabiting there has been an increase in living apart together (LAT), which is “a monogamous intimate partnership between unmarried individuals who live in separate homes but identify themselves as a committed couple” (Benson & Coleman, 2016, p. 797). This trend has been found in several nations and is motivated by:

- A strong desire to be independent in day-to-day decisions

- Maintaining their own home

- Keeping boundaries around established relationships

- Maintaining financial stability

Besides the desire to be autonomous, there is also a need for companionship, sexual intimacy, and emotional support. According to Bensen and Coleman, there are differences in LAT among older and younger adults. Those who are younger often enter into LAT out of circumstances, such as the job market, and they frequently view this arrangement as a transitional stage. In contrast, 80% of older adults reported that they did not wish to cohabitate or marry. For some it was a conscious choice to live more independently. For instance, older women desired the LAT lifestyle as a way of avoiding the traditional gender roles that are often inherent in relationships where couples live together. However, some older adults become LATs because they fear social disapproval from others if they were to live together.

Gay and Lesbian Elders

Approximately 3 million older adults in the United States identify as lesbian or gay (Hillman & Hinrichsen, 2014). By 2025 that number is expected to rise to more than 7 million (National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2006). Despite the increase in numbers, older lesbian and gay adults are one of the least researched demographic groups, and the research there is portrays a population faced with discrimination. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2011), compared to heterosexuals, lesbian and gay adults experience disparities in both physical and mental health. More than 40% of lesbian and gay adults ages 50 and over suffer from at least one chronic illness or disability and compared to heterosexuals they are more likely to smoke and binge drink (Hillman & Hinrichsen, 2014). Additionally, gay older adults have an increased risk of prostate cancer (Blank, 2005) and infection from HIV and other sexually transmitted illnesses (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008). When compared to heterosexuals, lesbian and gay elders have less support from others as they are twice as likely to live alone and four times less likely to have adult children (Hillman & Hinrichsen, 2014).

Lesbian and gay older adults who belong to ethnic and cultural minorities, conservative religions, and rural communities may face additional stressors. Ageism, heterocentrism, sexism, and racism can combine cumulatively and impact the older adult beyond the negative impact of each individual form of discrimination (Hillman & Hinrichsen, 2014). David and Knight (2008) found that older gay black men reported higher rates of racism than younger gay black men and higher levels of perceived ageism than older gay white men.

LGBT Elder Care. Approximately 7 million LGBT people over age 50 will reside in the United States by 2030, and 4.7 million of them will need elder care. Decisions regarding elder care is often left for families, and because many LGBT people are estranged from their families and do not have children of their own, they are left in a vulnerable position when seeking living arrangements (Alleccia & Bailey, 2019). A history of discriminatory policies, such as housing restricted to married individuals involving one man and one woman, and stigma associated with LGBT people make them especially vulnerable to negative housing experiences when looking for elder care.

Although lesbian and gay older adults face many challenges, more than 80% indicate that they engage in some form of wellness or spiritual activity (Fredrickson-Goldsen et al., 2011). They also gather social support from friends and “family members by choice” rather than legal or biological relatives (Hillman & Hinrichsen, 2014). This broader social network provides extra support to gay and lesbian elders.

An important consideration when reviewing the development of gay and lesbian older adults is the cohort in which they grew up (Hillman & Hinrichsen, 2014). The oldest lesbian and gay adults came of age in the 1950’s when there were no laws to protect them from victimization. The baby boomers, who grew up in the 1960’s and 1970’s, began to see states repeal laws that criminalized homosexual behavior. Future lesbian and gay elders will have different experiences due to the legal right for same-sex marriage and greater societal acceptance. Consequently, just like all those in late adulthood, understanding that gay and lesbian elders are a heterogeneous population is important when understanding their overall development.

Physical Development

Physical Changes of Aging

The Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging (BLSA) (NIA, 2011b) began in 1958 and has traced the aging process in 1,400 people from age 20 to 90. Researchers from the BLSA have found that the aging process varies significantly from individual to individual and from one organ system to another. However, some key generalization can be made including:

- Heart muscles thicken with age

- Arteries become less flexible

- Lung capacity diminishes

- Kidneys become less efficient in removing waste from the blood

- Bladder loses its ability to store urine

- Brain cells also lose some functioning, but new neurons can also be produced.

Many of these changes are determined by genetics, lifestyle, and disease. Other changes in late adulthood include:

Body Changes. Everyone’s body shape changes naturally as they age. According to the National Library of Medicine (2014) after age 30 people tend to lose lean tissue, and some of the cells of the muscles, liver, kidney, and other organs are lost. Tissue loss reduces the amount of water in the body and bones may lose some of their minerals and become less dense (a condition called osteopenia in the early stages and osteoporosis in the later stages). The amount of body fat goes up steadily after age 30, and older individuals may have almost one third more fat compared to when they were younger. Fat tissue builds up toward the center of the body, including around the internal organs.

Skin, Hair and Nails. With age skin loses fat, and becomes thinner, less elastic, and no longer looks plump and smooth. Veins and bones can be seen more easily, and scratches, cuts, and bumps can take longer to heal. Years of exposure to the sun may lead to wrinkles, dryness, and cancer. Older people may bruise more easily, and it can take longer for these bruises to heal. Some medicines or illnesses may also cause bruising. Gravity can cause skin to sag and wrinkle, and smoking can wrinkle skin as well. Also, seen in older adulthood are age spots, previously called “liver spots”. They look like flat, brown spots and are often caused by years in the sun. Skin tags are small, usually flesh-colored growths of skin that have a raised surface. They become common as people age, especially for women, but both age spots and skin tags are harmless (NIA, 2015f).

Nearly everyone has hair loss as they age, and the rate of hair growth slows down as many hair follicles stop producing new hairs (U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2019). The loss of pigment and subsequent graying begun in middle adulthood continues during late adulthood. The body and face also lose hair. Facial hair may grow coarser. For women this often occurs around the chin and above the upper lip. For men the hair of the eyebrows, ears, and nose may grow longer. Nails, particularly toenails, may become hard and thick. Lengthwise ridges may develop in the fingernails and toenails. However, pits, lines, changes in shape or color of fingernails should be checked by a healthcare provider as they can be related to nutritional deficiencies or kidney disease (U.S. National Library of Medicine).

Height and Weight. The tendency to become shorter as one ages occurs among all races and both sexes. Height loss is related to aging changes in the bones, muscles, and joints. A total of 1 to 3 inches in height is lost with aging. People typically lose almost one-half inch every 10 years after age 40, and height loss is even more rapid after age 70. Changes in body weight vary for men and woman. Men often gain weight until about age 55, and then begin to lose weight later in life, possibly related to a drop in the male sex hormone testosterone. Women usually gain weight until age 65, and then begin to lose weight. Weight loss later in life occurs partly because fat replaces lean muscle tissue, and fat weighs less than muscle. Diet and exercise are important factors in weight changes in late adulthood (National Library of Medicine, 2014).

Sarcopenia is the loss of muscle tissue as a natural part of aging. Sarcopenia is most noticeable in men, and physically inactive people can lose as much as 3% to 5% of their muscle mass each decade after age 30, but even people who are active still lose muscle (Webmd, 2016). Symptoms include a loss of stamina and weakness, which can decrease physical activity and subsequently shrink muscles further. Sarcopenia typically increases around age 75, but it may also speed up as early as 65 or as late as 80. Factors involved in sarcopenia include a reduction in nerve cells responsible for sending signals to the muscles from the brain to begin moving, a decrease in the ability to turn protein into energy, and not receiving enough calories or protein to sustain adequate muscle mass. Any loss of muscle is important because it lessens strength and mobility, and sarcopenia is a factor in frailty and the likelihood of falls and fractures in older adults. Maintaining strong leg and heart muscles are important for independence. Weight-lifting, walking, swimming, or engaging in other cardiovascular exercises can help strengthen muscles and prevent atrophy.

Sensory Changes in Late Adulthood

Vision. In late adulthood, all the senses show signs of decline, especially among the oldest-old. In the last chapter, you read about the visual changes that were beginning in middle adulthood, such as presbyopia, dry eyes, and problems seeing in dimmer light. By later adulthood these changes are much more common. Three serious eyes diseases are also more common in older adults: cataracts, macular degeneration, and glaucoma. Only the first can be effectively cured in most people.

Cataracts are a clouding of the lens of the eye. The lens of the eye is made up of mostly water and protein. The protein is precisely arranged to keep the lens clear, but with age some of the protein starts to clump. As more of the protein clumps together the clarity of the lens is reduced. While some adults in middle adulthood may show signs of cloudiness in the lens, the area affected is usually small enough not to interfere with vision. More people have problems with cataracts after age 60 (NIH, 2014b) and by age 75, 70% of adults will have problems with cataracts (Boyd, 2014). Cataracts also cause a discoloration of the lens, tinting it more yellow and then brown, which can interfere with the ability to distinguish colors such as black, brown, dark blue, or dark purple.

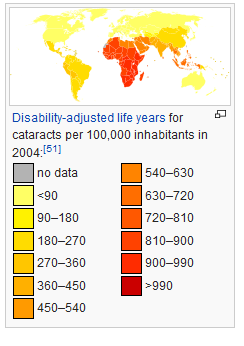

Risk factors besides age include certain health problems such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and obesity, behavioral factors such as smoking, other environmental factors such as prolonged exposure to ultraviolet sunlight, previous trauma to the eye, long-term use of steroid medication, and a family history of cataracts (NEI, 2016a; Boyd, 2014). Cataracts are treated by removing and replacing the lens of the eye with a synthetic lens. In developed countries, such as the United States, cataracts can be easily treated with surgery.

However, in developing countries, access to such operations are limited, making cataracts the leading cause of blindness in late adulthood in the least developed countries (Resnikoff, Pascolini, Mariotti & Pokharel, 2004). As shown in Figure 10.6, in areas of the world with limited medical treatment for cataracts, people are living more years with a serious disability. For example, of those living in the darkest red color on the map, more than 990 out of 100,00 people have a shortened lifespan due to the disability caused by cataracts.

Older adults are also more likely to develop age-related macular degeneration, which is the loss of clarity in the center field of vision, due to the deterioration of the macula, the center of the retina. Macular degeneration does not usually cause total vision loss, but the loss of the central field of vision can greatly impair day-to-day functioning. There are two types of macular degeneration: dry and wet. The dry type is the most common form and occurs when tiny pieces of a fatty protein called drusen form beneath the retina. Eventually the macular becomes thinner and stops working properly (Boyd, 2016). About 10% of people with macular degeneration have the wet type, which causes more damage to their central field of vision than the dry form. This form is caused by an abnormal development of blood vessels beneath the retina. These vessels may leak fluid or blood causing more rapid loss of vision than the dry form.

The risk factors for macular degeneration include smoking, which doubles your risk (NIH, 2015a); race, as it is more common among Caucasians than African Americans or Hispanics/Latinos; high cholesterol; and a family history of macular degeneration (Boyd, 2016). At least 20 different genes have been related to this eye disease, but there is no simple genetic test to determine your risk, despite claims by some genetic testing companies (NIH, 2015a). At present, there is no effective treatment for the dry type of macular degeneration. Some research suggests that some patients may benefit from a cocktail of certain antioxidant vitamins and minerals, but results are mixed at best. They are not a cure for the disease nor will they restore the vision that has been lost. This “cocktail” can slow the progression of visual loss in some people (Boyd, 2016; NIH, 2015a). For the wet type, medications that slow the growth of abnormal blood vessels and surgery, such as laser treatment to destroy the abnormal blood vessels, may be used. Unfortunately, only 25% of those with the wet version typically see improvement with these procedures (Boyd, 2016).

A third vision problem that increases with age is glaucoma, which is the loss of peripheral vision, frequently due to a buildup of fluid in eye that damages the optic nerve. As we age the pressure in the eye may increase causing damage to the optic nerve. The exterior of the optic nerve receives input from retinal cells on the periphery, and as glaucoma progresses more and more of the peripheral visual field deteriorates toward the central field of vision. In the advanced stages of glaucoma, a person can lose their sight entirely. Fortunately, glaucoma tends to progresses slowly (NEI, 2016b).

- Figure 10.7. A normal range of vision

- Figure 10.8. View with macular degeneration

- Figure 10.9. View with glaucoma

- Figure 10.10. View with cataracts

Glaucoma is the most common cause of blindness in the U.S. (NEI, 2016b). African Americans over age 40, and everyone else over age 60, have a higher risk for glaucoma. Those with diabetes, and with a family history of glaucoma also have a higher risk (Owsley et al., 2015). There is no cure for glaucoma, but its rate of progression can be slowed, especially with early diagnosis. Routine eye exams to measure eye pressure and examination of the optic nerve can detect both the risk and presence of glaucoma (NEI, 2016b). Those with elevated eye pressure are given medicated eye drops. Reducing eye pressure lowers the risk of developing glaucoma or slow its progression in those who already have it.

Hearing. As you read previously, our hearing declines both in terms of the frequencies of sound we can detect, and the intensity of sound needed to hear as we age. These changes continue in late adulthood. Almost 1 in 4 adults aged 65 to 74 and 1 in 2 aged 75 and older have disabling hearing loss (NIH, 2016). Table 10.3 lists some common signs of hearing loss.

Table 10.3 Common Signs of Hearing Loss

| *Have trouble hearing over the telephone |

| *Find it hard to follow conversations when two or more people are talking |

| *Often ask people to repeat what they are saying |

| *Need to turn up the TV volume so loud that others complain |

| *Have a problem hearing because of background noise |

| *Think that others seem to mumble |

| *Cannot understand when women and children are speaking |

adapted from NIA, 2015c

Presbycusis is a common form of hearing loss in late adulthood that results in a gradual loss of hearing. It runs in families and affects hearing in both ears (NIA, 2015c). Older adults may also notice tinnitus, a ringing, hissing, or roaring sound in the ears. The exact cause of tinnitus is unknown, although it can be related to hypertension and allergies. It may come and go or persist and get worse over time (NIA, 2015c). The incidence of both presbycusis and tinnitus increase with age and males around the world have higher rates of both (McCormak, Edmondson-Jones, Somerset, & Hall, 2016).

Your auditory system has two jobs: To help you to hear, and to help you maintain balance. Your balance is controlled when the brain receives information from the shifting of hair cells in the inner ear about the position and orientation of the body. With age, the functionality of the inner ear declines, which can lead to problems with balance when sitting, standing, or moving (Martin, 2014).

Taste and Smell. Our sense of taste and smell are part of our chemical sensing system. Our sense of taste, or gustation, appears to age well. Normal taste occurs when molecules that are released by chewing food stimulate taste buds along the tongue, the roof of the mouth, and in the lining of the throat. These cells send messages to the brain, where specific tastes are identified. After age 50, we start to lose some of these sensory cells. Most people do not notice any changes in taste until their 60s (NIH: Senior Health, 2016b). Given that the loss of taste buds is very gradual, even in late adulthood, many people are often surprised that their loss of taste is most likely the result of a loss of smell.

Our sense of smell, or olfaction, decreases with age, and problems with the sense of smell are more common in men than in women. Almost 1 in 4 males in their 60s have a disorder with the sense of smell, compared to 1 in 10 women (NIH: Senior Health, 2016b). This loss of smell due to aging is called presbyosmia. Olfactory cells are located in a small area high in the nasal cavity. These cells are stimulated via two pathways: when we inhale through the nose, or via the connection between the nose and the throat when we chew and digest food. It is a problem with this second pathway that explains why some foods such as chocolate or coffee seem tasteless when we have a head cold. There are several types of loss of smell. Total loss of smell, or anosmia, is extremely rare.

Problems with our chemical senses can be linked to other serious medical conditions such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, or multiple sclerosis (NIH: Senior Health, 2016a). Any sudden changes in sensory sensitivity should be checked out. Loss of smell can change a person’s diet, with either a loss of enjoyment of food and eating too little for balanced nutrition, or adding sugar and salt to foods that are becoming blander to the palette.

Table 10.4 Types of Smell Disorders

| Presbyosmia | Smell loss due to aging |

| Hyposmia | Loss of only certain odors |

| Anosmia | Total loss of smell |

| Dysosmia | Change in the perception of odors. Familiar odors are distorted |

| Phantosmia | Smell odors that are not present |

adapted from NIH Senior Health: Problems with Smell

Touch. Research has found that with age, people may experience reduced or changed sensations of vibration, cold, heat, pressure, and pain (Martin, 2014). Many of these changes are also consistent with a number of medical conditions that are more common among the elderly, such as diabetes. However, there are also changes in touch sensations among healthy older adults. The ability to detect changes in pressure have been shown to decline with age, with more pronounced losses during the 6th decade and diminishing further with advanced age (Bowden & McNelty, 2013). Yet, there is considerable variability, with almost 40% of the elderly showing sensitivity that is comparable to younger adults (Thornbury & Mistretta, 1981). However, the ability to detect the roughness/ smoothness or hardness/softness of an object shows no appreciable change with age (Bowden & McNulty, 2013). Those who show decreasing sensitivity to pressure, temperature, or pain are at risk for injury (Martin, 2014), as they can injure themselves without detecting it.

Pain. According to Molton and Terrill (2014), approximately 60%-75% of people over the age of 65 report at least some chronic pain, and this rate is even higher for those individuals living in nursing homes. Although the presence of pain increases with age, older adults are less sensitive to pain than younger adults (Harkins, Price, & Martinelli, 1986). Farrell (2012) looked at research studies that included neuroimaging techniques involving older people who were healthy and those who experienced a painful disorder. Results indicated that there were age-related decreases in brain volume in those structures involved in pain. Especially noteworthy were changes in the prefrontal cortex, brainstem, and hippocampus.

Women are more likely to report feeling pain than men (Tsang et al., 2008). Women have fewer opioid receptors in the brain, and women also receive less relief from opiate drugs (Garrett, 2015). Because pain serves an important indicator that there is something wrong, a decreased sensitivity to pain in older adults is a concern because it can conceal illnesses or injuries requiring medical attention.

Chronic health problems, including arthritis, cancer, diabetes, joint pain, sciatica, and shingles are responsible for most of the pain felt by older adults (Molton & Terrill, 2014). Cancer is a special concern, especially “breakthrough pain” which is a severe pain that comes on quickly while a patient is already medicated with a long-acting painkiller. It can be very upsetting, and after one attack many people worry it will happen again. Some older individuals worry about developing an addiction to pain medication, but if medicine is taken exactly as prescribed, addiction should not be a concern (NIH, 2015b). Lastly, side effects from pain medicine, including constipation, dry mouth, and drowsiness, may occur that can adversely affect the elder’s life.

Some older individuals put off going to the doctor because they think pain is just part of aging and nothing can help. Of course, this is not usually true. Managing pain is crucial to ensure feelings of well-being for the older adult. When chronic pain is not managed, the individual tends to restrict their movements for fear of feeling pain or injuring themselves further. This lack of activity will result in more restriction, further decreased participation, and greater disability (Jensen, Moore, Bockow, Ehde, & Engel, 2011). A decline in physical activity because of pain is also associated with weight gain and obesity in adults (Strine, Hootman, Chapman, Okoro, & Balluz, 2005). Additionally, sleep and mood disorders, such as depression, can occur (Moton & Terrill, 2014). Learning to cope effectively with pain is an important consideration in late adulthood and working with one’s primary physician or a pain specialist is recommended (NIH, 2015b).

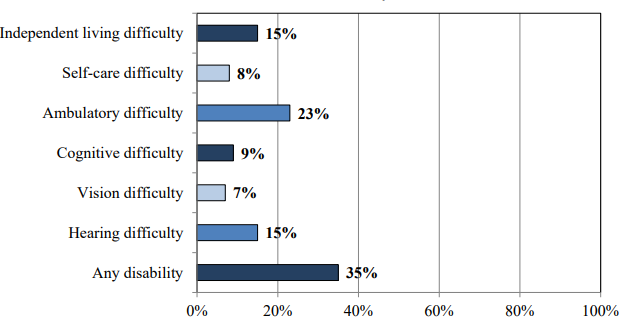

Of those 65 and older, 35% have a disability. Figure 10.11 identifies the percentage of those who have a disability based on the type.

Brain Functioning

Research has demonstrated that the brain loses 5% to 10% of its weight between 20 and 90 years of age (Fjell & Walhovd, 2010). This decrease in brain volume appears to be due to the shrinkage of neurons, decreases in the number of synapses, and increasingly shorter axon lengths. According to Garrett (2015), normal declines in cognitive ability throughout the lifespan are associated with brain changes, including reduced activity of genes involved in memory storage, synaptic pruning, plasticity, and glutamate and GABA (neurotransmitters) receptors.

There is also a loss in white matter connections between brain areas. Without myelin, neurons demonstrate slower conduction and impede each other’s actions. A loss of synapses occurs in specific brain areas, including the hippocampus (involved in memory) and the basal forebrain region. Older individuals also activate larger regions of their attentional and executive networks, located in the parietal and prefrontal cortex, when they perform complex tasks. This increased activation coincides with reduced performance on both executive tasks and tests of working memory when compared to that of younger people (Kolb & Whishaw, 2011).

Continued Neurogenesis. Researchers at the University of Chicago found that new neurons continue to form into old age. Tobin et al. (2019) examined post-mortem brain tissue of individuals between the ages of 79 and 99 (average age 90.6) and found evidence of neurogenesis in the hippocampus. Approximately 2000 neural progenitor cells and 150, 000 developing neurons were found per brain, although the number of developing neurons was lower in people with cognitive impairments or Alzheimer’s disease. Tobin et al. hypothesized that the lower levels of neurogenesis in the hippocampus were associated with symptoms of cognitive decline and reduced synaptic plasticity.

The brain in late adulthood also exhibits considerable plasticity, and through practice and training, the brain can be modified to compensate for any age-related changes (Erber & Szuchman, 2015). Park and Reuter-Lorenz (2009) proposed the Scaffolding Theory of Aging and Cognition which states that the brain adapts to neural atrophy (dying of brain cells) by building alternative connections, referred to as scaffolding. This scaffolding allows older brains to retain high levels of performance. Brain compensation is especially noted in the additional neural effort demonstrated by those individuals who are aging well. For example, older adults who performed just as well as younger adults on a memory task used both prefrontal areas, while only the right prefrontal cortex was used in younger participants (Cabeza, Anderson, Locantore, & McIntosh, 2002). Consequently, this decrease in brain lateralization appears to assist older adults with their cognitive skills.

Healthy Brain Functioning. In longitudinal studies, Cheng (2016) found that both physical activity and stimulating cognitive activity resulted in significant reductions in the risk of neurocognitive disorders. Physical activity, especially aerobic exercise, is associated with less age-related gray and white matter loss, as well and diminished neurotoxins in the bra

Overall, physical activity preserves the integrity of neurons and brain volume. Cognitive training improves the efficiency of the prefrontal cortex and executive functions, such as working memory, and strengthens the plasticity of neural circuits. Both activities support cognitive reserve, or “the structural and dynamic capacities of the brain that buffer against atrophies and lesions” (Cheng, 2016, p. 85). Although it is optimal to begin physical and cognitive activities earlier in life, it is never too late to start these programs to improve one’s cognitive health, even in late adulthood.

Can we improve brain functioning? Many training programs have been created to improve brain functioning. ACTIVE (Advanced Cognitive Training for Independent and Vital Elderly), a study conducted between 1999 and 2001 in which 2,802 individuals age 65 to 94, suggests that the answer is “yes”. These racially diverse participants received 10 group training sessions and 4 follow up sessions to work on tasks of memory, reasoning, and speed of processing. These mental workouts improved cognitive functioning even 5 years later. Many of the participants believed that this improvement could be seen in everyday tasks as well (Tennstedt et al., 2006).

However, programs for the elderly on memory, reading, and processing speed training demonstrate that there is improvement on the specific tasks trained, but there is no generalization to other abilities (Jarrett, 2015). Further, these programs have not been shown to delay or slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Although these programs are not harmful, “physical exercise, learning new skills, and socializing remain the most effective ways to train your brain” (p. 207). These activities appear to build a reserve to minimize the effects of primary aging of the brain.

Women and Aging

In Western society, aging for women is much more stressful than for men as society emphasizes youthful beauty and attractiveness (Slevin, 2010). The description that aging men are viewed as “distinguished” and aging women are viewed as “old” is referred to as the double standard of aging (Teuscher & Teuscher, 2006). Since women have traditionally been valued for their reproductive capabilities, they may be considered old once they are postmenopausal. In contrast, men have traditionally been valued for their achievements, competence, and power, and therefore are not considered old until decades later when they are physically unable to work (Carroll, 2016). Consequently, women experience more fear, anxiety, and concern about their identity as they age, and may feel pressure to prove themselves as productive and valuable members of society (Bromberger, Kravitz, & Chang, 2013).

Attitudes about aging, however, do vary by race, culture, and sexual orientation. In some cultures, aging women gain greater social status. For example, as Asian women age they attain greater respect and have greater authority in the household (Fung, 2013). Compared to white women, Black and Latina women possess fewer stereotypes about aging (Schuler et al., 2008). Lesbians are also more positive about aging and looking older than heterosexual women (Slevin, 2010). The impact of media certainly plays a role in how women view aging by selling anti-aging products and supporting cosmetic surgeries to look younger (Gilleard & Higgs, 2000).

Cognition, Wisdom, and Spirituality

How Does Aging Affect Information Processing?

There are many stereotypes regarding older adults– as forgetful and confused, but what does the research on memory and cognition in late adulthood reveal? Memory comes in many types, such as working, episodic, semantic, implicit, and prospective. There are also many processes involved in memory. Thus it should not be a surprise that there are declines in some types of memory and memory processes, while other areas of memory are maintained or even show some improvement with age. In this section, we will focus on changes in memory, attention, problem solving, intelligence, post-formal cognition, and wisdom, including the effects of stereotypes that exaggerate these losses in the elderly.

Memory

Changes in Working Memory. Working memory is the more active, effortful part of our memory system. Working memory is composed of three major systems: The phonological loop that maintains information about auditory stimuli, the visuospatial sketchpad, that maintains information about visual stimuli, and the central executive, that oversees working memory, allocating resources where needed and monitoring whether cognitive strategies are being effective (Schwartz, 2011).

Schwartz reports that it is the central executive that typically shows the most marked declines with age. In tasks that require allocation of attention between different stimuli, older adults fare worse than do younger adults. In a study by Göthe, Oberauer, and Kliegl (2007) older and younger adults were asked to learn two tasks simultaneously. Young adults eventually managed to learn and perform both tasks without any loss in speed and efficiency, although it did take considerable practice. None of the older adults were able to accomplish this. Yet, when asked to learn each task individually, older adults could perform just as well as young adults. Having older adults learn and perform both tasks together was just too taxing for the central executive. In contrast, in working memory tasks that do not require much input from the central executive, such as the digit span test, which predominantly uses the phonological loop, older adults perform on par with young adults (Dixon & Cohen, 2003).

Changes in Long-term Memory. Long-term memory is divided into semantic (knowledge of facts), episodic (memories of specific events), and implicit (stored procedural skills, classical conditioning, and priming) memory. Semantic and episodic memory are part of the explicit memory system, which requires conscious effort to create and retrieve. Several studies consistently reveal that episodic memory shows greater age-related declines than semantic memory (Schwartz, 2011; Spaniol, Madden, & Voss, 2006).

It has been suggested that episodic memories may be harder to encode and retrieve because they contain at least two different types of memory (1) the event and (2) when and where the event took place. In contrast, semantic memories are not tied to any particular geography or time line. Thus, only the knowledge needs to be encoded or retrieved (Schwartz, 2011). Spaniol et al. (2006) found that retrieval of semantic information was considerably faster for both younger and older adults than the retrieval of episodic information, with there being little difference between the two age groups for retrieval of semantic memories. They note that older adults’ poorer performance on episodic memory appeared to be related to slower processing of the information and the difficulty of the task. They found that as tasks became more difficult, the gap between the two age groups’ performance widened, but more so for tasks involving episodic than semantic memory tasks.

Studies that examine general knowledge (semantic memory) of topics such as politics and history (Dixon, Rust, Feltmate, & See, 2007) or vocabulary/lexical memory (Dahlgren, 1998) often find that older adults outperform younger adults. However, older adults do find that they experience more “blocks” at retrieving information that they know. In other words, they experience more tip-of-the-tongue (TOT) events than do younger adults (Schwartz, 2011). memory blocks are especially common for the retrieval of “nonsense words”or specific concept labels. Unfortunately for older adults, nonsense words include the names of people, places, and things (like movies, restaurants, or books)– which represent many common topics of conversation.

Implicit memory requires little conscious effort and often involves skills or more habitual patterns of behavior. This type of memory shows few declines with age. Many studies assessing implicit memory measure the effects of priming. Priming refers to changes in behavior as a result of frequent or recent experiences. for example, if you were shown pictures of food and asked to rate their appearance and then later were asked to complete words such as s_ _ p, you may be more likely to write “soup” than “soap” or “ship.” The images of food “primed” your memory for words connected to food. Does this type of memory and learning change with age? The answer is typically “no” for most older adults (Schacter, Church, & Osowiecki, 1994).

Prospective memory refers to remembering things we need to do in the future, such as remembering a doctor’s appointment or to take medication before bedtime. It has been described as “the flip-side of episodic memory” (Schwartz, 2011, p. 119). Episodic memories are the recall of events in our past, while the focus of prospective memories is of events in our future. In general, humans are fairly good at prospective memory if they have little else to do in the meantime. However, when there are competing tasks that also demand our attention, this type of memory rapidly declines. One explanation given for this phenomenon is that this form of memory draws on the central executive of working memory, and when this component of working memory is absorbed in other tasks, our ability to remember to do something else in the future is more likely to slip out of memory (Schwartz, 2011).

However, prospective memories are often divided into time-based prospective memories, such as having to remember to do something at a future time, or event-based prospective memories, such as having to remember to do something when a certain event occurs. When age-related declines are found, they are more likely to be time-based, rather than event-based, and in laboratory settings rather than in the real-world, where older adults can show comparable or slightly better prospective memory performance (Henry, MacLeod, Phillips & Crawford, 2004; Luo & Craik, 2008). This should not be surprising given the tendency of older adults to be more selective in where they place their physical, mental, and social energy. Having to remember a doctor’s appointment is of greater concern than remembering to hit the space-bar on a computer every time the word “tiger” is displayed, and outside the lab many more compensatory aids (e.g., post-it notes, calendars, phone alarms) are readily available.

Recall versus Recognition. Memory performance often depends on whether older adults are asked to simply recognize previously learned material or recall material on their own. Generally, for all humans, recognition tasks are easier because they require less cognitive energy. Older adults show roughly equivalent memory to young adults when assessed with a recognition task (Rhodes, Castel, & Jacoby, 2008). However, in recall tasks, older adults show memory deficits in comparison to younger adults. While the effect is initially not that large, starting at age 40 adults begin to show regular age-graded declines in recall memory compared to younger adults (Schwartz, 2011).

The Age Advantage. Fewer age differences are observed when memory cues are available, such as for recognition memory tasks, or when individuals can draw upon acquired knowledge or experience. For example, older adults often perform as well if not better than young adults on tests of word knowledge or vocabulary. Expertise often comes with age, and research has pointed to areas where aging experts perform quite well. For example, older typists were found to compensate for age-related declines in speed by looking farther ahead at printed text (Salthouse, 1984). Compared to younger players, older chess experts focus on a smaller set of possible moves, leading to greater cognitive efficiency (Charness, 1981). Accrued knowledge of everyday tasks, such as grocery prices, can also help older adults make better decisions than young adults (Tentori, Osheron, Hasher, & May, 2001).

Attention and Problem Solving

Changes in Attention in Late Adulthood. Changes in sensory functioning and speed of processing information in late adulthood often translate into changes in attention (Jefferies et al., 2015). Research has shown that older adults are less able to selectively focus on information while ignoring distractors (Jefferies et al., 2015; Wascher, Schneider, Hoffman, Beste, & Sänger, 2012), although Jefferies and her colleagues found that when given double time, older adults could perform at the same level as young adults. Other studies have also found that older adults have greater difficulty shifting their attention between objects or locations (Tales, Muir, Bayer, & Snowden, 2002).

Consider the implication of these attentional changes for older adults. How does maintenance or loss of cognitive ability affect older adults’ everyday lives? Researchers have studied cognition in the context of several different everyday activities. One example is driving. Although older adults often have more years of driving experience, cognitive declines related to reaction time or attentional processes may pose limitations under certain circumstances (Park & Gutchess, 2000). In contrast, research on interpersonal problem solving suggests that older adults use more effective strategies than younger adults to navigate through social and emotional problems (Blanchard-Fields, 2007). In the context of work, researchers rarely find that older individuals perform more poorly on the job (Park & Gutchess, 2000). Similar to everyday problem solving, older workers may develop more efficient strategies and rely on expertise to compensate for cognitive declines.

Problem Solving. Declines with age are found on problem-solving tasks that require processing non-meaningful information quickly– a kind of task that might be part of a laboratory experiment on mental processes. However, many real-life challenges facing older adults do not rely on speed of processing or making choices on one’s own. Older adults resolve everyday problems by relying on input from others, such as family and friends. They are also less likely than younger adults to delay making decisions on important matters, such as medical care (Strough, Hicks, Swenson, Cheng & Barnes, 2003; Meegan & Berg, 2002).

What might explain these deficits as we age? The processing speed theory, proposed by Salthouse (1996, 2004), suggests that as the nervous system slows with advanced age our ability to process information declines. This slowing of processing speed may explain age differences on a variety of cognitive tasks. For instance, as we age, working memory becomes less efficient (Craik & Bialystok, 2006). Older adults also need longer time to complete mental tasks or make decisions. Yet, when given sufficient time (to compensate for declines in speed), older adults perform as competently as do young adults (Salthouse, 1996). Thus, when speed is not imperative to the task, healthy older adults generally do not show cognitive declines.

In contrast, inhibition theory argues that older adults have difficulty with tasks that require inhibitory functioning, or the ability to focus on certain information while suppressing attention to less pertinent information (Hasher & Zacks, 1988). Evidence comes from directed forgetting research. In directed forgetting people are asked to forget or ignore some information, but not other information. For example, you might be asked to memorize a list of words but are then told that the researcher made a mistake and gave you the wrong list and asks you to “forget” this list. You are then given a second list to memorize. While most people do well at forgetting the first list, older adults are more likely to recall more words from the “directed-to-forget” list than are younger adults (Andrés, Van der Linden, & Parmentier, 2004).

Aging stereotypes exaggerate cognitive losses. While there are information processing losses in late adulthood, many argue that research exaggerates normative losses in cognitive functioning during old age (Garrett, 2015). One explanation is that the type of tasks that people are tested on tend to be meaningless. For example, older individuals are not motivated to remember a random list of words in a study, but they are motivated for more meaningful material related to their life, and consequently perform better on those tests. Another reason is that researchers often estimate age declines from age differences found in cross-sectional studies. However, when age comparisons are conducted longitudinally (thus removing cohort differences from age comparisons), the extent of loss is much smaller (Schaie, 1994).