Gender Development

Learning Objectives: Gender Development

- What is the overall developmental task of constructing a “gender identity”?

- What is the difference between “sex” and “gender”?

- Be able to define multiple facets of a society’s “gender curriculum,” including gender roles and gender stereotyping.

- What is “psychological androgyny” and how is it connected to adjustment, flexibility, and well-being?

- Summarize four major theories explaining gender development, namely, social learning theory, neurophysiological bases, cognitive developmental theory, and gender schema theory.

- What meta-theory underlies each theory?

- How does a dynamic systems approach incorporate all four of these theories?

- What are the six major age-graded milestones in gender development?

- Name the six areas in which gender differences in psychological functioning have typically been found. How big are these differences?

The task of gender development is a complex biopsychosocial process that takes place in concert with societal stereotypes and the local social contexts they shape. The empirical picture is not complete, but it seems that gender identities are complex internalized cognitive and emotional representations that children and youth construct for themselves over time, based on the biological and temperamental givens that each one comes with and their cumulative interactions with the social worlds of family, school, peers, and society. Much of gender development seems to reflect cognitive changes that allow children to successively realize and try to make sense of different aspects of gender identity, but the whole kit-n-caboodle seems to be built on a foundation created by biological or neurophysiological givens. We will trace the main age-graded milestones that children experience in constructing their own gender identities, in order to suggest ways in which parents (and other adults) can support children’s and adolescents’ healthy development.

Gender development is a fascinating process because it is deeply rooted in biology, profoundly shaped by societal expectations, and actively constructed by individuals over and over again at different developmental levels. All theories of gender identity posit that the processes shaping its development are both biological and societal, so it is important to get straight on those biological and social processes before we turn to development. This is also a fascinating historical moment to study gender development because science is revealing more and more about its biological and psychological complexity, just as society is undergoing a gender revolution in which people are questioning, exploring, and recognizing a much broader spectrum of gender and sexual identities.

Biopsychosocial Processes of Gender

The terms sex and gender are often used interchangeably, although they have different meanings. In this context, sex refers to biological categories (traditionally, either male or female) as defined by physical differences in genetic composition and in reproductive anatomy and function. On the other hand, gender refers to the cultural, social, and psychological meanings that are associated with particular biopsychosocial categories, like masculinity and femininity (Wood & Eagly, 2002), which vary depending on other intersectional factors, like race, ethnicity, and culture.

Historically, the terms gender and sex have been used interchangeably. Because of this, gender is often viewed as a binary – a person is either male or female – and it is assumed that a person’s gender matches their biological sex. However, recent research challenges both of those assumptions. Although most people identify with the gender that matches their natal sex (cisgender), some of the population (estimates range from 0.6 to 3 percent) identify with a gender that does not match the sex they were assigned at birth (transgender; Flores, Herman, Gates, & Brown, 2016; see box). For example, an individual assigned as male based on biological characteristics may identify as female, or vice versa. Researchers have also been increasingly examining the long-held assumption that biological sex is binary (e.g., Carothers & Reis, 2013; Hyde, Bigler, Joel, Tate, & van Anders, 2019). Although it has always been clear that there are more than two biological sexes, for example individuals who are intersex (see box), more recently scientists have identified dozens of markers of sexuality outside of the reproductive system (e.g., genetic, epigenetic, hormonal, endocrine, neurophysiological, psychological, social). People have a range of different combinations of these characteristics, suggesting that biological sex is more complex and multifaceted than a binary category.

Beyond the Binary in Biological Sex

Some individuals are intersex or sex diverse; that is born with either an absence or some combination of male and female reproductive organs, sex hormones, or sex chromosomes (Jarne & Auld, 2006). In humans, intersex individuals make up a small but significant proportion of world’s population; with recent estimates ranging between .05 and 2 percent (Blackless et al., 2000). There are dozens of intersex conditions, and intersex individuals demonstrate some of the diverse variations of biological sex. Some examples of intersex conditions include:

• Turner syndrome or the absence of, or an imperfect, second X chromosome

• Congenital adrenal hyperplasia or a genetic disorder caused by an increased production of androgens

• Androgen insensitivity syndrome or when a person has one X and one Y chromosome, but is resistant to the male hormones or androgens

Greater attention to the rights of children born intersex is occurring in the medical field, and intersex children and their parents should work closely with specialists to ensure these children develop positive gender identities.

Research has also begun to conceptualize gender in ways beyond the gender binary. Genderqueer or gender nonbinary are umbrella terms used to describe a wide range of individuals who do not identify with and/or conform to the gender binary. These terms encompass a variety of more specific terms that individuals may use to describe themselves. Some common terms are genderfluid, agender, and bigender. An individual who is genderfluid may identify as male, female, both, or neither at different times and in different circumstances. An individual who is agender may have no gender or describe themselves as having a neutral gender, while bigender individuals identify as two genders.

It is important to remember that sex and gender do not always match and that gender is not always binary; however, a large majority of prior research examining gender has not made these distinctions. As such, many of the following sections will discuss gender as a binary. Throughout, we will consider the development of “gender-nonconforming” children. This is a broad and heterogeneous group of children and adults whose gender development does not fit within societal dictates. Because societal expectations are so narrow, there are many ways not to conform, and we mention a few here, just to give a flavor of these alternative pathways. All of them are healthy and positive, but children and adolescents who follow these pathways need social validation and protection from gender discrimination and bullying. Activists are leading global movements that will push society to reinvent its views of the wide variety of sexualities and gender identities that have always been with us.

Transgender Children

Many young children do not conform to the gender roles modeled by the culture and push back against assigned roles. However, a small percentage of children actively reject the toys, clothing, and anatomy of their assigned sex and state they prefer the toys, clothing, and anatomy of the opposite sex. A recent study suggests that approximately three percent of youth identify as transgender or identifying with a gender different from their natal sex (Rider, McMorris, Gower, Coleman, & Eisenberg, 2018). Many transgender adults report that they identified with the opposite gender as soon as they began talking (Russo, 2016). Some of these children may experience gender dysphoria, or distress accompanying a mismatch between one’s gender identity and biological sex (APA, 2013), while other children do not experience discomfort regarding their gender identity.

As they grow up, some transgender individuals alter their bodies through medical interventions, such as surgery and hormonal therapy, so that their physical being is better aligned with their gender identity. However, not all transgender individuals choose to alter their bodies or physically transition. Many maintain their original anatomy but present themselves to society as a different gender, often by adopting the dress, hairstyle, mannerisms, or other characteristics typically assigned to a certain gender. It is important to note that people who cross-dress, or wear clothing that is traditionally assigned to the opposite gender, such as transvestites, drag kings, and drag queens, do not necessarily identify as transgender (although some do). People often confuse the term transvestite, which is the practice of dressing and acting in a style or manner traditionally associated with another sex (APA, 2013) with transgender. Cross-dressing is typically a form of self-expression, entertainment, or personal style, and not necessarily an expression of one’s gender identity.

Sexual Orientation

A person’s sexual orientation is their emotional and sexual attraction to a particular gender. It is a personal quality that inclines people to feel romantic or sexual attraction (or a combination of these) to persons of a given sex or gender. According to the American Psychological Association (APA) (2016), sexual orientation also refers to a person’s sense of identity based on those attractions, related behaviors, and membership in a community of others who share those attractions. Sexual orientation is independent of gender; for example, a transgender person may identify as heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, pansexual, polysexual, asexual, or any other kind of sexuality, just like a cisgender person.

Sexual Orientation on a Continuum. Sexuality researcher Alfred Kinsey was among the first to conceptualize sexuality as a continuum rather than a strict dichotomy of gay or straight. To classify this continuum of heterosexuality and homosexuality, Kinsey et al. (1948) created a seven-point rating scale that ranged from exclusively heterosexual to exclusively homosexual. Research conducted over several decades has supported this idea that sexual orientation ranges along a continuum, from exclusive attraction to the opposite sex/gender to exclusive attraction to the same sex/gender (Carroll, 2016).

However, sexual orientation can be defined in many ways. Heterosexuality, which is often referred to as being straight, is attraction to individuals of the opposite sex/gender, while homosexuality, being gay or lesbian, is attraction to individuals of one’s own sex/gender. Bisexuality was a term traditionally used to refer to attraction to individuals of either male or female sex, but it has recently been used in nonbinary models of sex and gender (i.e., models that do not assume there are only two sexes or two genders) to refer to attraction to any sex or gender. Alternative terms such as pansexuality and polysexuality have also been developed, referring to attraction to all sexes/genders and attraction to multiple sexes/genders, respectively (Carroll, 2016).

Asexuality refers to having no sexual attraction to any sex/gender. According to Bogaert (2015) about one percent of the population is asexual. Being asexual is not due to any physical problems, and the lack of interest in sex does not necessarily cause the individual any distress. Asexuality is being researched as a distinct sexual orientation.

Societal Expectations about Gender: Gender Roles and Stereotypes

Children develop within cultures that have a “gender curriculum” that prescribes what it means to be male and female. These include gender roles and gender stereotypes. Gender roles are the expectations associated with being male or female. Children learn at a young age that there are distinct behaviors and activities deemed to be appropriate for boys and for girls. These roles are acquired through socialization, a process through which children learn to behave in a particular way as dictated by societal values, beliefs, and attitudes. Gender stereotyping goes one step further: it involves overgeneralizing about the attitudes, traits, or behavior patterns of women or men. For boys and men, expectations and stereotypes include characteristics like “tough” or “brave” or “assertive”, and for girls and women characteristics like “nice” and “nurturing” and “affectionate.” You might be saying to yourself, “but I can be most of those things, sometimes”—and you are right. People of all genders frequently enact roles that are stereotypically assigned to only men or women.

Psychological androgyny. One area of research on gender expectations has examined differences between people who identify with typically masculine or feminine gender roles. Researchers gave men and women lists of positive masculine traits (emphasizing agency and assertiveness) and feminine traits (emphasizing gentleness, compassion, and awareness of others’ feelings), and asked them to rate the extent to which those traits applied to them. Some people reported identifying highly with mostly masculine traits or identifying highly with mostly feminine traits, but some people did not identify strongly with either (this group was called “undifferentiated”), and a final group identified strongly with both masculine and feminine traits; this last group was called “androgynous” (Bem, 1977). Psychological androgyny is when people display both traditionally male and female gender role characteristics – people who are both strong and emotionally expressive, both caring and confident.

Which group reported the best psychological functioning? On the one hand, those with more “masculine” traits (the masculine and androgynous groups) tend to have higher self-esteem and lower internalizing symptoms (Boldizar, 1991; DiDonato & Berenbaum 2011). (This may be because “masculine” traits like being self-reliant, self-assured, and assertive are closely related to these outcomes.) On the other hand, there is a cost to missing out on “feminine” traits as well, since things like relationships, emotions, and communication are central to human well-being. In general, studies find that psychologically androgynous people, who report high levels of both male and female characteristics are more adaptable and flexible (Huyck, 1996; Taylor & Hall, 1982), and seem to fare better in general, when considering many areas of adjustment (compared to those with masculine or feminine traits alone; Pauletti, et al. 2017). It may be no surprise that, in general, it is most adaptive to be able to draw on the whole spectrum of human traits (Berk, 2014).

Processes of Gender Development

Four major psychological theories highlight multiple explanatory processes through which children develop gender identities. Most of these theories focus on gender typing, which depicts the processes through which children become aware of their gender, and adopt the values, attributes, objects, and activities of members of the gender they identify as their own.

- A primary perspective on gender development is provided by social learning theory. Consistent with mechanistic meta-theories, this theory argues that behavior is learned through observation, modeling, reinforcement, and punishment (Bandura, 1997). Each society has its own “gender curriculum,” which leads to differential expectations and treatment starting at birth. Children are rewarded and reinforced for behaving in concordance with gender roles and punished for breaking gender roles. Social learning theory also posits that children learn many of their gender roles by observing and modeling the behavior of older children and adults, and in doing so, learn the behaviors that are appropriate for each gender. In this process, fathers seem to play a particularly important role.

- A second perspective, consistent with maturational meta-theories, focuses on biological and neurophysiological factors that are present at birth. This theory underscores the idea, present in research on gender expression, sexual orientation, and gender identity, that children come with a firm biological foundation for their gender and sexual preferences; these include genes, chromosomes, and hormones (Roselli, 2018). Like temperament, infants seem to come with “gender stuff” that, depending how well it matches current social categories, can influence how they respond to expectations and pressures for conformity.

- A third perspective, consistent with organismic meta-theories, focuses on cognitive developmental theory. This approach holds that children’s understanding about gender and its meaning depend completely on their current stage of cognitive development. At birth, children have no idea that gender as a category even exists or that they may belong to one of them. As their developmental capacities grow, toddlers and then young children can successively represent and understand more and more complex aspects of gender-related identity. These cognitive stages provide some of the clearest age-graded milestones in the development of gender identity, such as the emergence of gender awareness (i.e., the recognition of one’s own gender) and gender constancy (i.e., the belief that gender is a fixed characteristic), which are described in more detail below.

- A fourth major theory, which emphasizes the active role of the child in constructing a gender identity, is called gender schema theory. Consistent with contextualist meta-theories, gender schema theory argues that children are active learners who essentially socialize themselves. In this case, children actively organize the behavior, activities, and attributes they observe into gender categories, which are known as schemas. These schemas then affect what children notice and remember later. People of all ages are more likely to remember schema-consistent behaviors and attributes than those that are schema-inconsistent. So, when they think of firefighters, people are more likely to remember men, and forget women. They also misremember schema-inconsistent information. If research participants are shown pictures of someone standing at the stove, they are more likely to remember the person to be cooking if depicted as a woman, and the person to be repairing the stove if depicted as a man. By remembering only schema-consistent information, gender schemas are strengthened over time.

All four processes highlighted in these theories play a role in gender development, which can be considered a biopsychosocial process: (1) as depicted by social learning theory, it is shaped by the society’s gender curriculum, through processes of observation, modeling, reinforcement, and punishment; (2) as depicted by biological theories, it is built on a strong neurophysiological foundation of preferences in gender expression, sexual orientation, and gender identity; (3) as explained by cognitive developmental theory, children’s understanding of gender shifts regularly as the complexity of their cognition grows; and (4) as explained by gender schema theory, a child’s gender identity is a work in progress, actively constructed through their own efforts and engagement with their social worlds.

Most recently, researchers have drawn on broader more integrative dynamic systems approaches to understand the development of gender identity (e.g., Fausto-Sterling, 2012; Martin & Ruble, 2010). These approaches attempt to explain how complex patterns of gender-related thought, behavior, and experience undergo qualitative shifts, including disruption, transformation, and reorganization, during different developmental windows. Researchers argue that “children’s ongoing physical interactions and psychological experiences with parents, peers, and culture fundamentally shape and reshape their experience of gender developmentally, as different brain and body systems couple and uncouple over time… In the end, gender is not a stable achievement, but rather ‘a pattern in time’ (Fausto-Sterling, 2012, p. 405) continually building on prior dynamics and adapting to current environments” (Diamond, p. 113).

Age-graded Milestones in Gender Development

1. Intrinsic gender and temperament. Research seems to suggest that newborns come with a neurophysiological package of “gender stuff” that provides an internal anchor for their preferences—including (at least) gender identity and sexual orientation, and perhaps temperamental characteristics, such as activity level, aggression, effortful control, and emotional reactivity. These internal anchors and expressive preferences seem to be part of an individual’s core identity. Scientists are not exactly sure what determines these intrinsic anchors; so far evidence suggests both genetic influences (e.g., as seen in twin studies, which find that sexual orientation and sexual non-conformity run in families; Van Beijsterveldt, Hudziak, & Boomsma, 2006) and the influence of the prenatal environment (e.g., maternal levels of androgens, antibodies to male hormones; Cohen-Bendahan, van de Beek, & Berenbaum, 2005).

Although each individual’s core identity likely exhibits some degree of malleability, which may make it easier for children to conform to society’s dictates, LGBTQ+ advocates and parents of gender-expansive children are rock-solid on one thing: These core identities are often clear to children and they cannot be ignored, subverted, or transformed through external pressures (Besser et al., 2006). Moreover, it violates children’s rights as humans, when parents or other members of society attempt to do so.

Development of Sexual Orientation

According to current scientific understanding, individuals are usually aware of their sexual orientation between middle childhood and early adolescence. However, this is not always the case, and some do not become aware of their sexual orientation until much later in life. It is not necessary to participate in sexual activity to be aware of these emotional, romantic, and physical attractions; people can be celibate and still recognize their sexual orientation. Some researchers argue that sexual orientation is not static and inborn but is instead fluid and changeable throughout the lifespan.

There is no scientific consensus regarding the exact reasons why an individual holds a particular sexual orientation. Research has examined possible biological, developmental, social, and cultural influences on sexual orientation, but there has been no evidence that links sexual orientation to only one factor (APA, 2016). However, evidence for biological explanations, including genetics, birth order, and hormones, will be summarized since many scientists argue that biological processes occurring during the embryonic and and early postnatal life play the central organizing role in sexual orientation (Balthazart, 2018).

Genetics. Using both twin and familial studies, heredity provides one biological explanation for same-sex orientation. Bailey and Pillard (1991) studied pairs of male twins and found that the concordance rate for identical twins was 52%, while the rate for fraternal twins was only 22%. Bailey, Pillard, Neale, and Agyei (1993) studied female twins and found a similar difference with a concordance rate of 48% for identical twins and 16% for fraternal twins. Schwartz, Kim, Kolundzija, Rieger, & Sanders (2010) found that gay men had more gay male relatives than straight men, and sisters of gay men were more likely to be lesbians than sisters of straight men.

Fraternal Birth Order. The fraternal birth order effect indicates that the probability of a boy identifying as gay increases for each older brother born to the same mother (Balthazart, 2018; Blanchard, 2001). According to Bogaret et al. “the increased incidence of homosexuality in males with older brothers results from a progressive immunization of the mother against a male specific cell-adhesion protein that plays a key role in cell-cell interactions, specifically in the process of synapse formation,” (as cited in Balthazart, 2018, p. 234). A meta-analysis indicated that the fraternal birth order effect explains the sexual orientation of between 15% and 29% of gay men.

Hormones. Excess or deficient exposure to hormones during prenatal development has also been theorized as an explanation for sexual orientation. One-third of females exposed to abnormal amounts of prenatal androgens, a condition called congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), identify as bisexual or lesbian (Cohen-Bendahan, van de Beek, & Berenbaum, 2005). In contrast, too little exposure to prenatal androgens may affect male sexual orientation by not masculinizing the male brain (Carlson, 2011).

2. Gender awareness. At about age 2-3, toddlers’ cognitive development allows them to begin to create representational categories to organize their conceptual thinking about the world. Gender is one of these categories. The ability to classify oneself as male or female is called “gender awareness.” Children’s biological and sexual profiles are built during conception and prenatal development, so they are typically assigned a biological sex at birth, but before toddlers develop the cognitive capacity to categorize, they are blissfully unaware of their gender. Although they have likely been receiving differential treatment from family members since they were born, it is not until they are able to recognize this category and apply it to themselves, that gender becomes psychologically real. Once small children become aware of gender categories, they begin taking notes about the differences between people in these two categories: names, colors, toys, jewelry, clothes, hair length, voices, behavior, and so on.

Baby X. It is important to note that, in a world without a gender curriculum, the list children would make of the differences between males and females would be very short: It would include only secondary sexual characteristics of adults and adolescents who are post-puberty. Babies and pre-pubescent children would not be distinguishable by gender– because they have no secondary sexual characteristics. We can imagine a thought experiment in which no one is subject to a gender curriculum. Imagine that each of us receives an envelope at birth with information about our biologically assigned sex inside, but we are not allowed to open it until it becomes relevant, that is, until we reach puberty. In this thought experiment, our parents and society would have to raise us so we would be ready to take on either gender role. They would have to select gender-neutral names, colors for the nursery and our clothes, toys, and so on. Many students find this idea intriguing but also a bit unsettling.

A similar thought experiment was described in an article in 1972 in Ms. Magazine entitled “The Story of X,” which describes parents who decided to raise their child without revealing its gender to the world (Gould, 1972). Several real parents, in Europe and the US, have also decided to raise their children without revealing their gender. It is fascinating to see how this kind of decision has been received by the media and by other parents. In each case, the firestorm of media attention was so dramatic that parents decided to withdraw their stories (and their children) from scrutiny by the press. Although developmentalists (and parents) can argue about the decision to shield children from society’s stereotypes as opposed to helping them recognize, counter, and transcend these stereotypes, the hysteria surrounding decisions to conceal a child’s gender are very telling about society’s view of the centrality of gender to every child’s identity, and society’s “right to know.”

Gender malleability. When “gender awareness” emerges during early childhood, a key part of the gender schema young children construct includes the notion that any gender categories that they observe are malleable. Because small children in the preoperational stage of cognitive development are not capable of inferring the essential underlying characteristics of gender (just as they cannot infer the defining characteristics of other categories, like animate objects), they see gender assignments as temporary and changeable. Most young children believe that a person can change from female to male (or vice versa) by cutting their hair or changing their clothes. Little boys often report that they will grow up to be Moms with babies in their tummies; little girls that they will grow up to be Dads. Many adults can remember this state of awareness. For example, one of our students told us about her preschool class in which all the 4-year-olds were boys; she thought that when she turned 4, she would also become a boy. She was looking forward to the transformation, the same way children look forward to getting taller or older or better at riding a bike.

Because many children discuss their desires (and plans) to cross gender lines, parents of gender-non-conforming or transgender children often see these kinds of declarations as a “phase” that children will get over. Parents cannot easily tell when children’s statements reflect real underlying convictions that they do not internally identify with the gender roles or expressions that have been assigned to them. However, some gender variant or transgender adults report that their real gender identity was already very clear to them at this age, and parents of such children also confirm that their children were letting them know through word and deed. In fact, the clarity and insistence on a gender variant identity at such a young age (and in the face of such enormous pressure to conform) provides some of the most convincing evidence that children come pre-loaded with their own gender and sexual orientation. At the same time, this narrative does not describe the only pathway. Some gender variant adults report that it was not until they were much older (and sometimes with the aid of therapeutic support) that they were able to understand what was/is happening to them in terms of gender identity and development.

Gender expression. The specific gender differences that show up in a child’s gender schema at this age depend on the local social context that the child experiences, which is why many parents decide to minimize young children’s exposure to gender-stereotypes . At the same time, for parents who do expect their children to conform to cultural prescriptions for gender-typical dress, toys, and activities, this is the age at which some parents of gender non-conforming or gender-variant children may begin to notice that their child has not gotten the cultural memo. Parents report unease about their boys’ exploration of female-stereotyped clothes (such as dresses, tutus, tiaras), accessories (such as high heels, purses, barrettes), toys (especially dolls and doll clothes), and colors—which is why these children have sometimes been dubbed “pink boys.”

Note that there has been no parallel study of “blue girls,” because tomboys do not as frequently alarm their parents at this age. Girls who play with masculine toys often do not face the same ridicule from adults or peers that boys face when they want to play with feminine toys (Leaper, 2015). Girls also face less ridicule when playing a masculine role (like doctor) as opposed to a boy who wants to take a feminine role (like caregiver). For an interesting segment on CNN, see “Why girls can be boyish but boys can’t be girlish.” As explained by Padawer (2012), “That’s because girls gain status by moving into “boy” space, while boys are tainted by the slightest whiff of femininity. ‘There’s a lot more privilege to being a man in our society,’ says Diane Ehrensaft, a psychologist at the University of California, San Francisco, who supports allowing children to be what she calls gender creative. ‘When a boy wants to act like a girl, it subconsciously shakes our foundation, because why would someone want to be the lesser gender?’ Boys are up to seven times as likely as girls to be referred to gender clinics for psychological evaluations. Sometimes the boys’ violation is as mild as wanting a Barbie for Christmas. By comparison, most girls referred to gender clinics are far more extreme in their atypicality: they want boy names, boy pronouns and, sometimes, boy bodies.”

Creation of a “middle space.” One surprisingly simple rule for parents who wish to encourage gender exploration and expansion is that “Colors are just colors, clothes are just clothes, and toys are just toys,” meaning that these societal prescriptions are not developmentally real or meaningful. Researchers refer to the overlap between male and female expectations and stereotypes as “the middle space,” and suggest that an important role for adults to take on is the expansion of this “middle space.” With the sanctioning of the “tomboy” identity, society has begun to allow girls to take up residence in this middle space. Its expansion for girls and its creation for boys are next steps for all of us. In general, the wider the gender expression enjoyed by children of all genders (e.g., girls in sports, boys in cooking, and so on), the healthier everyone’s gender identity development is likely to be.

3. Gender constancy. When children reach the concrete operational stage of cognitive development (between ages 5 and 7), they are able to infer that, according to societal dictates, the essential defining feature of maleness and femaleness is, traditionally, based on genitalia. This is also the age at which children are able to infer the inverse principle: If genitalia dictate gender, then all males by necessity have penises and all females have vaginas–which they are often happy to announce at Kindergarten or in other public places. Following from this discovery, children also begin to grasp the fact that their assignment into gender categories is permanent, unchangeable, or constant.

The realization that one is a life-time member of the “boys club” or the “girls club” typically leads to greater interest and more focus on the membership requirements for their particular club. In stereotyped social contexts, children’s attitude toward conformity to “gender-appropriate” markers may shift from descriptive to prescriptive, in which children so highly identify with markers from their own club, that they begin to denigrate or become repelled by markers of the “wrong” club. These behaviors become visible in boy’s resistance to being asked to wear “girl colors” or play “girl games.” It is also noticeable in children’s attempts to enforce these categories on others—either directly through instructions (“you have to ride a girl’s bike”) and statements of fact (“this slide is only for boys,”), or indirectly through teasing, taunting, criticism, and ridicule towards any child who crosses the lines.

For gender-nonconforming children or transgender children, this is an age where the psychological costs of society’s gender boxes and lines can become apparent. At this age, children can start to sense (or clearly know) that they have been permanently assigned to a biological sex that comes with a narrow gender expression or an eventually gendered-body whose physicality is not consonant with their own internal needs or identity. If so, then confusion or (more or less strong) feelings of gender dissonance may emerge. In the clinical literature, these feelings are sometimes labeled “gender dysphoria” to indicate the sadness and desperation that children may feel when they realize that they have been permanently assigned to the “wrong” gender expression, gender identity, and/or biological sex.

The dangers of pushing children into boxes. LGBTQ advocates point out how crucial it is to create some space for children around these issues to allow them to figure out for themselves where they stand on the many dimensions of gender. For some children, exploring gender expression is just that—they need to spend time in the “middle space.” If we have to categorize, these children are gender non-conforming in expression, but gender-conforming in identity and sexual orientation. This can be seen in how annoyed some “pink boys” who wear dresses and long hair become when people mistake them for girls (Padawer, 2012). When asked why this was so annoying, one little guy named P.J. told the reporter about a boy in his third-grade class who is a soccer fanatic. “He comes to school every day in a soccer jersey and sweat pants,” P. J. said, “but that doesn’t make him a professional soccer player.” It’s as if these children need to remind adults about the essential defining features of male and female biological sex. P.J. could say, “Duh—I still have a penis, so I am still a boy.”

For other children, exploring gender expression is the beginning of the realization that their sexual orientation may not be heterosexual, that they may be gay, lesbian, and/or bisexual. Some writers have tried to quantify the numbers of gender-nonconforming boys, suggesting that 2-7% of boys display nonconforming gender behavior, and of these 60-80% grow up to be gay men (Padawer, 2012). The same tendency is suggested for lesbian women, most of whom identified as “tomboys.” It seems that these numbers would be very difficult to confirm, given that more than 75% of women identify as “tomboys” and most of them are heterosexual, and given the stringent attempts to shove gender nonconforming boys back into their boxes which means that we are only observing the most determined and tenacious nonconforming boys.

For some children, gender non-conforming behavior is the beginning of the realization that they are transgender. Some children are very clear on this early on, and insist on names, pronouns, and gender expressions that are consonant with their own internal convictions about their actual gender. Other children need the opportunity to explore and question, and they may not become clear on their sexual orientation or transgender status until they reach puberty or later.

Parents of gender non-conforming children. Gender non-conforming children may be more or less clear about why they need to explore the “middle space,” but some parents are just confused. Most of us have been fully socialized in the current gender curriculum and so any activity outside those lines and boxes may seem deeply “wrong” or even “unnatural.” That is always the way with strong societal norms. In the 1800s, if a woman showed a glimpse of ankle, she was considered to be immoral; in the 1920s, women wearing pants and short hair were seen as “unnatural;” in the 1960s, boys whose hair touched their collars were suspended from school.

Gender non-conforming children provide their adults with the opportunity and motivation to improve society in ways that are more positive for everyone. The need that all children have for their parents’ full love and support encourages adults to grow outside of their comfort zones, and to develop into better parents. As Brill and Pepper (2008) point out, “It takes courage to follow the path of love.” They provide many good strategies and resources for parents who are trying to follow this path. They point out that some of parents’ reluctance can be based on their fear of others looking down on them and criticizing their parenting. We think that many parents can relate to this fear—even in little ways, such as when a child throws a fit in the store or we are called into school for a child’s infraction. We are worried that our parenting is inadequate or that others will think we are inferior parents. That is one important reason why Brill and Pepper (2008) insist that parents get support for themselves (from therapists or groups of like-minded parents) so the they will be able in turn to provide acceptance and support for their children.

Some of the reluctance of parents of transgender children can be based in grief over the loss of their previous child. We think that many parents can also relate to this feeling—when we look at photos of our children as babies and young children, we miss those darling little versions of our children. At the same time, we know that they are still there in the core identity of our older children. And parents of gender variant children can be comforted with the idea that the essence of their child, their child’s core, is still there, and still intact. Most parents also feel vindicated when they see their child’s distress and depression lift (some children are actually suicidal), and watch them bloom in their new affirmed identity, showing joy and delight in the free expression of their authentic selves.

Dealing with discrimination and bullying. An important part of parents’ reluctance to support gender variant children can be based on fears about the reactions their children may encounter in school, church, or other public places. Parents are not wrong about these reactions, and their desire to protect their children is understandable. These same issues have been faced by parents of children who belong to racial, ethnic, and cultural minorities—who also have to face messages of hate, discrimination, and oppression. One difference may be that some parents feel that their gender variant child could avoid all these upsetting experiences if only they would conform, whereas most Black parents do not see the solution to racism as encouraging their children to “pass” as white. Research on parenting children from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds suggests that the most helpful approach involves proud support for a child’s minority status and engaged participation with minority communities, combined with realistic training about how to deal constructively with incidents of intolerance. Some parenting guides suggest strategies organized around the notions of: (1) Talk: speak up for what you believe; (2) Walk: find a safe space; and (3) Squawk: find someone who will support you.

At the same time, many parents may surprise themselves by becoming staunch advocates for their children’s rights and activists in the larger societal movement for gender respect and equality. Luckily, as parents work hard to see that their children are treated fairly everywhere they go, there are good programs that can be used to improve schools. These programs train teachers, administrators, and staff how to celebrate and support gender diversity. The good news is that such trainings can have positive effects for everyone involved.

4. Gender latency. A fourth major developmental milestone takes place during middle childhood, sometimes referred to as the “latency” stage or phase, and loosely modeled after Freud’s description of children’s psychosexual stages. During this period (about ages 8 or 9 until puberty), children seem to be less active in working out issues explicitly connected to gender or sexual identity. In general, children seem to be more mellow or laid back about the whole “gender thing,” largely recognizing that scripts about gender-appropriate signifiers (like colors, behaviors, or activities) are societal conventions and not true moral issues. At this age, children seem to relax their enforcement of gender rules and the “yuckiness” of the opposite sex begins to fade. Many gender variant children, during this period, also seem to relax, maybe deciding that non-conformity is more trouble than it is worth, and so (at least temporarily) adopting conventional signifiers that are more aligned with their biological sex.

For parents who are worried about the effects of hetero-normative gender stereotypes, it can feel like your child has made it safely through the gender curriculum and come out whole on the other side. For parents who are worried about their gender-nonconforming children, it can also feel like the “problem” has been solved and it was (after all) just a phase.

5. Puberty and the gender police. A fifth major milestone in gender development is ushered in by puberty, which usually starts between ages 10-12 for girls and between ages 12-14 for boys. The reality of biological changes in both primary and secondary sexual characteristics seems to trigger a major shift, not only in children’s neurophysiology, but also in their psychological systems and social relationships. When puberty strikes, the issue of what it means to be male and female in this historical moment seems to come to center stage, and teenagers in middle school and early high school seem to be trying to enact and rigidly enforce all of society’s current stereotypes about gender. This process is labeled “gender intensification” and it will be more or less “intense” depending on the local culture, their stereotypes, and the rigidity with which they are viewed.

Gender intensification. This is the moment at which adolescents seem to want to wring any gender variation out of themselves and their peers, and this goes for kids who vary on expression, identity, sexual orientation, and transgender status—which basically includes everyone. So pressure is exerted on girls to look and act more like girls—and we see girls try to bring themselves into line with cultural stereotypes about the value of beauty through increased use of make-up, clothes, and hairstyles as well as through a focus on diet, exercise, and eating disorders; we also see normative losses in self-esteem as girls find themselves unable to reach these idealized female appearances and increasingly internalize a negative body image. The pressure that is exerted on boys to look and act like boys can be observed as boys try to bring themselves into line with cultural stereotypes about the value of power, through adolescents’ increased use of aggression and bullying, boys’ frequent lapses into silence, as well as increased focus on body building and the abuse of steroids. Both genders are at risk for commodifying the opposite sex—girls can regard “boyfriends” as status objects just as boys can regard girls as sexual targets. Perhaps surprisingly, the local external pressures to adhere to societal gender stereotypes seem to originate largely within gender, in that girls tighten the screws on other girls to conform whereas boys are the ones who are pressuring other boys. During early adolescence, some researchers refer to the phase of gender intensification as a period that is run by the “gender police.”

It is important to note that the gender harassment and bullying that is still so common in schools and neighborhoods is often aimed at heterosexual youth who do not conform to societal boxes and lines, such as late-maturing boys who are small, slight, and shy. Of course, the further that a child strays over gender lines, the more they are likely to become targets of harassment and bullying, not only by peers but also by parents, teachers, and societal institutions.

Gender contraction. In a way this phase could also be referred to as a period of “gender contraction,” in that some adolescents fall over themselves to jump back into the boxes and over the lines prescribed by society, especially in terms of gender expression. However, the onset of puberty also brings additional biological information to some adolescents, indicating (or verifying) that they may be (or definitely are) gay, lesbian, bisexual, queer, or transgender. This new information (or clarity) comes at exactly the same time that the external world brings increased pressure for them to conform. Such social pressures (and the internal pressures they can create) can collide with adolescents’ natural sexual urges to create confusion and internal gridlock. For some youth, when their internal states (biological urges, gender identity, and sexual orientation) are aligned, they may achieve internal clarity—“Ah-ha, I’m gay (or lesbian or bisexual)!” Some adults describe this process as “coming out to oneself.” But for many gender variant youth, external pressure and homophobia can make this process feel very confusing and dangerous. For these children, their adolescent peers (and often parents, siblings, and teachers) feel more like “gender Nazis.”

Pause on puberty. For some youth, the beginnings of puberty may trigger an awareness of (or verify) their transgender status—“My body is going the wrong direction here—wait!” In fact, one cutting edge strategy for children who may be transgender is to stop the transformation—literally using hormone blockers that halt the onset of puberty. This strategy creates a space that preserves children’s options. It is much easier physiologically to transition to another gender before puberty has been completed. This allows for a transition that is more complete and requires fewer surgeries. For parents of transgender children who want to give their child the opportunity to make an autonomous informed decision, the use of hormone blockers allows children to continue developing cognitively so that their decision can be made using all the capacities of formal operations. Families also benefit from the participation of experienced therapists and physicians, who can help guide them in the sequence and timing of each step.

LGBTQ advocates also insist that it is important to follow the child’s lead, and not to get ahead of them. Some families can be so confused by a child’s non-conforming gender expression that they pressure the child to change their biological sex in order to produce a child who is culturally “aligned” in expression, identity, and biology. In fact, as previously mentioned, many transgender individuals do not choose to make a physical transition at all.

In every case, children need full family support in order to negotiate the external pressures they will likely experience and otherwise internalize. If transgender teens decide to transition during high school, some experts recommend allowing the child to take a year off from school or be home-schooled for a year, so that they are sheltered from external scrutiny. Some families also decide that the child should then return with their new identity to a different school, but other transgender teens report that an important part of the process of self-acceptance is the experience of winning over support from their current peers. In their stories of transition (Kuklin, 2014), some teens seem remarkably understanding of the reluctance and flak they experience in forging a new identity, even though all of them make clear that such resistance (and in many cases overt hostility) causes real pain and suffering.

6. Identity development during college and the freedom to explore and expand. For many youth, the full development of an authentic gender identity doesn’t take place until after high school, which is why the college years are such a common time for gender confirming and non-conforming youth to be working on issues of gender identity and sexual orientation. Developmentally, these are good years for many reasons. In most strata of society, the “gender police” start to fade during mid-adolescence and, by emerging adulthood, most forms of gender expression are again viewed as conventions and not as moral prescriptions, so the previously intense external pressures are often more relaxed (again—depending on local geographical and religious perspectives).

Youth themselves have newly emerging meta-cognitive capacities to reflect on their own internalized stereotypes and shame, allowing them to be able to rework for themselves their own attitudes about gender and sexuality. Because many students are working on these issues, college is also a place where questioning youth can more easily find open and understanding social and sexual partners with whom they can safely explore these issues. Moreover, college campuses can be places that provide formal resources (e.g., Queer Resource Center, LGBTQ groups) and informal role models, that encourage youth to discover, liberate, and celebrate their authentic selves.

Exploration and commitment. During the years of emerging adulthood, many youth are figuring out that they can create their own narratives about what it means to be male and female in society. Many will affirm a positive appraisal of their assigned sex as an anchor of their gender identity, but at the same time accept and enjoy a wide-ranging set of expressions, activities, and roles that are vastly expanded compared to societal stereotypes. In fact, increasingly, many will come to view the “middle space” as occupying pretty much all the space depicting gender roles, so much so that for many young adults, the issues surrounding biological sex, that is, being male or female, begin to shrink until gender is a very small, almost incidental, part of their identity. Of course, young adults often return to these issues and what they mean as they approach the developmental task of “intimacy,” which is often worked on in the context of sexual relationships.

Some LGBTQ youth report that emerging adulthood was a good time for them to deal with these issues because they needed to wait until they had worked out other less-contested aspects of their identity so they could be strong and self-confident enough to face and explore issues of sexual orientation and gender identity in a society that is so openly hostile to gender expansion. For example, some youth reported feeling mixed up about gender identity and sexual orientation. Some transgender youth felt that they were not allowed to be sexually attracted to people who were of the sex opposite to their original biological sex. For example, if I am assigned a female biological sex at birth and later realize that I am an affirmed (transgender) male, what does it mean if I am attracted to biological males? Does that threaten my identity as an affirmed male? During early adulthood, transgender youth can come to accept what LGBTQ experts confirm—that transgender status and sexual orientation are separate issues. An affirmed male who is attracted to other men is a gay transgender male person. All combinations are possible.

Sex/Gender Differences

As part of the study of gender development, researchers are also interested in examining sex/gender differences in psychological characteristics and behaviors. Researchers who favor different meta-theoretical perspectives often assume that gender differences are due to underlying differences in biology (consistent with maturational metatheories) or differences in socialization (consistent with mechanistic meta-theories). However, consistent with contextualist meta-theories, to date most of the differences that have been found have turned out to be a complex combination of neurophysiological sex differences (e.g. the effects of sex hormones on behavior), gender roles (i.e., differences in how men and women are supposed to act), gender stereotypes (i.e., differences in how we think men and women are), and gender socialization.

What are these gender differences? Research suggests that they are concentrated in six areas.

- Activity level. In terms of temperament, boys show higher activity levels starting at birth, as seen in differences in muscle tone, muscle mass, and movement; as they get older, boys remain somewhat more active and have more difficulty in activities that require holding still. Some of the biggest differences involve the play styles of children. Boys frequently play organized rough-and-tumble games in large groups, while girls often play less-physical activities in much smaller groups (Maccoby, 1998).

- Verbal ability. Girls develop language skills earlier and know more words than boys. They show slightly higher verbal abilities, including reading and writing, all throughout school, and are somewhat more emotionally expressive (of fear and sadness, but not anger).

- Visuo-spatial ability. Boys perform slightly better than girls on tests of visuo-spatial ability (e.g., tests of mentally rotating 3-D objects), differences which can later be seen in activities like map reading or sports that require spatial orientation.

- Verbal and physical aggression. Starting at about the age of 2, boys exhibit higher rates of unprovoked physical aggression than girls, although no gender differences have been found in provoked aggression (Hyde, 2005). At every age, boys show higher levels of physical aggression, but starting in adolescence, girls show higher levels of relational aggression (e.g., social shunning, gossiping, power exertion).

- Self-regulation and prosocial behavior. At about the same age that gender differences in aggression emerge (approximately age 2), gender differences also emerge in levels of self-regulation, compliance, empathy, and prosocial behavior. Girls show better behavioral and emotional self-regulation, whereas boys have more trouble minding and following rules and routines. As they get older boys are also slightly less able to suppress inappropriate responses and slightly more likely to blurt things out than girls (Else-Quest, Hyde, Goldsmith, & Van Hulle, 2006). At the same time, girls are also more likely to offer praise, to agree with the person they’re talking to, and to elaborate on the other person’s comments; boys, in contrast, are more likely to assert their opinion and offer criticisms (Leaper & Smith, 2004). The combination of higher levels of aggression and lower levels of self-regulation is a primary reason why, compared to girls, boys at every age are more likely to be disciplined (as well as suspended and expelled) in school.

- Developmental vulnerability. One of the biggest and most consistent set of sex/gender differences between girls and boys is found in the area of developmental vulnerability. Boys are more likely than girls to show markers of a wide range of biological and psychological vulnerabilities, including prenatal and perinatal stress and disease (e.g., lower survival rates in premature birth, higher rates of infant mortality and death from SIDS), learning disabilities (e.g., dyslexia, speech defects, mental retardation), neurological conditions (e.g., autism, attention deficit disorder, hyperactivity), and mental health conditions (e.g., opposition/defiant disorder, schizophrenia). Starting in early adolescence, compared to girls, boys are more likely to be involved in acts of anti-social behavior, delinquency, and violent crime, and to be incarcerated. Unlike differences in psychological characteristics, which tend to be small and inconsistent, gender differences in these markers of vulnerability tend to be large and robust. For example, rates of ADHD and autism are 3-5 times higher in boys, and over 90% of inmates are male. Differences in diagnosis may represent actual differences in incidence, or conditions may present differently in girls than in boys.

The only mental health conditions more prevalent in girls are internalizing disorders (i.e., depression and anxiety) but boys have higher rates of completed suicide at every age, with an increasing gap over adulthood, until by age 65 over 70% of suicides are committed by men. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20190313-why-more-men-kill-themselves-than-women

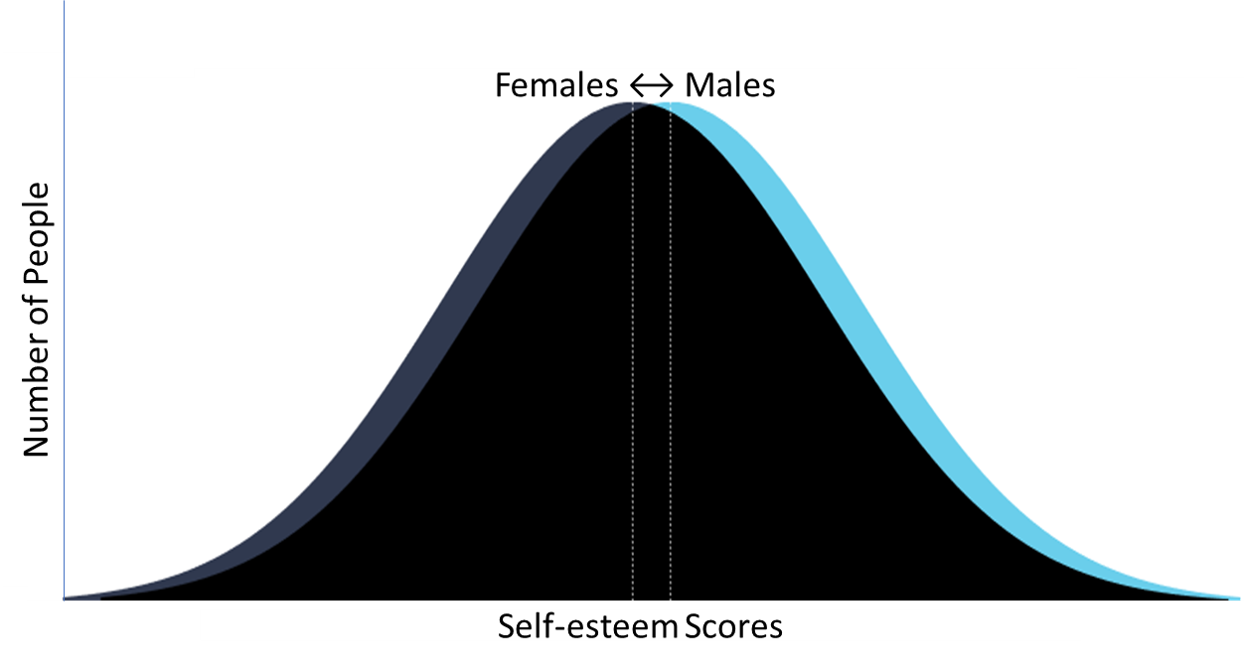

Magnitude of gender differences. It is important to note that, with the exception of sex/gender differences in physical characteristics (e.g., height and muscle mass) and developmental vulnerability, sex/gender differences in psychological characteristics and behaviors tend to be quite small, inconsistent, and change over historical time. Even where sex/gender differences are found, there is a great deal of variation among females and among males, meaning that individual boys are very different from one another as are individual girls. As a result, knowing someone’s gender does not help much in predicting their actual attributes or behaviors. For example, in terms of activity level, boys are considered more active than girls. However, 42% of girls are more active than the average boy (but so are 50% of boys). Figure 1 depicts this phenomenon in a comparison of male and female self-esteem. The two bell-curves show the range in self-esteem scores within boys and within girls, and there is enormous overlap. The average gender difference, shown by the arrow at the top of the figure, is tiny compared to the variation within gender.

Furthermore, few gender differences reflect innate biological differences, but instead reflect complex mixtures of neurophysiological and social factors, with a special emphasis on the specific societal and familial gender curriculum that creates sets of differential opportunities, treatment, and experiences for girls and boys. For example, one small gender difference is that boys show better spatial abilities than girls. However, Tzuriel and Egozi (2010) gave girls the chance to practice their spatial skills (by imagining a line drawing was different shapes) and discovered that, with practice, this gender difference completely disappeared. Likewise, those differences also disappear in groups of girls who are involved in sports which require spatial practice. The fact that gender differences that previously were significant (e.g., boys performed better on math achievement tests during early adolescence) have disappeared over time suggests that they are largely a function of environmental differences (in this case, the number of math classes taken).

Some of the most interesting research on sex/gender differences today critiques this entire area of work and argues that many domains that we assume differ across genders, including some described here in your textbook, are really based on gender stereotypes and not actual differences. Researchers conducted large meta-analyses (statistical analyses that allow researchers to systematically combine findings across an entire body of studies) of thousands of studies across more than a million participants, and concluded that: Girls are not more fearful, shy, or scared of new things than boys; boys are not more angry than girls and girls are not more emotional than boys; boys do not perform better at math than girls; and girls are not more talkative than boys (Hyde, 2005). These meta-analyses have also been conducted on studies involving adults, with much the same conclusion (Carothers & Reis, 2013; Hyde, Bigler, Joel, Tate, & van Anders, 2019).

Liberating Society from Status Hierarchies of Gender and Sexuality

Societies play a crucial role in gender development by trying to dictate hierarchies of human worth based on gender and sexuality. Gender is multi-faceted and so status hierarchies cover biological sex, gender expression, sexual orientation, and identity. Hierarchies are apparent in the relative value placed on males versus females, on people who are heterosexual versus lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, and transgender, and on people who conform to the gender binary versus people who do not. Some of these hierarchies are enshrined in law, for example, when women were not allowed to vote, or homosexuality was illegal, or laws refuse to recognize the legitimacy of transgender sexual identities.

These status hierarchies are enforced in all the ways we discussed in previous readings on higher-order contexts of development, including implicit bias, prejudice, stereotypes, segregation, exclusion, and discrimination. Discrimination persists throughout the lifespan in the form of obstacles to education, or lack of access to political, financial, and social power. Status hierarchies also involve entrenched myths about subgroups who fall into different rungs of the societal ladders of these hierarchies, and cover stories that membership in some of these groups is voluntary and something youth should “get over.” The negative stories society tells are hurtful, especially if children and youth internalize them. At the same time, the development of people at the top of these hierarchies can also be adversely affected, as when narrow definitions of masculinity can impede the development of boys and men, and narrow definitions of heterosexuality can interfere with the sexual exploration of youth.

Societal myths about gender minorities are especially harmful when they infect parents and families who are supposed to be protecting children and promoting their development. For children from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds, their staunchest supporters typically are parents, extended family, and racial and ethnic communities, who counteract these myths and provide counter-narratives of positivity, pride, and cultural heritage. However, for children from gender minorities, parents and families may not serve this vital role. Because parents often do not share their child’s gender identity, and may sometimes even harbor entrenched myths of revulsion, children from gender minorities do not always have the layers of protection provided by extended family, that serve to buffer them from the worst of society’s prejudices. In fact, some of the most hurtful messages may come from family and friends. These status hierarchies and the entrenched myths used to enforce them create hazardous conditions for the development of children and youth. A growing realization of their extent and severity should create an even greater sense urgency for taking collective action to abolish them. In the meantime women’s groups and the LGBTQ+ community are creating safe spaces where their members can experience the support and validation they deserve and develop strategies for resistance and resilience.

These issues are of global concern (WHO, 2011). Although we are rightfully worried about status hierarchies in the US, many countries around the world have much worse (and sometimes life-threatening) conditions for women and girls, LGBTQ+ youth and adults, and gender minorities. For example, in some countries where gender preferences are pronounced, it is no longer legal to give parents information on the sex of their fetus because selective abortion of females has created a gender imbalance that is noticeable at the national level. In many cultures, women do not have access to basic rights (e.g., to education, freedom of movement, choice of spouses and sexual partners, etc.), and sexual minorities who express their preferences openly do so at risk of imprisonment and death.

What are the impacts of enforcing gender stereotypes and valuing or devaluing particular gender identities?

Like all status hierarchies, these societal conditions exert a downward pressure on healthy development. In the United States, the stereotypes that boys should be strong, forceful, active, dominant, and rational, and that girls should be pretty, subordinate, unintelligent, emotional, and talkative are portrayed in children’s toys, books, commercials, video games, movies, television shows, and music. These messages dictate not only how people should act, but also the opportunities they are given, how they are treated, and the extent to which they can grow into their full potential. Even into college and professional school, women are less vocal in class and much more at risk for sexual harassment from teachers, coaches, classmates, and professors. These patterns are also found in social interactions and in media messages. In adulthood, these differences are reflected in income gaps between men and women (women working full-time earn about 74 percent the income of men), in higher rates of women targeted for rape and domestic violence, higher rates of eating disorders for females, and in higher rates of violent death for men in young adulthood.

The effects of discrimination and bullying can also be seen in disparities in physical and mental health for youth who belong to minority gender identities and sexual orientations (see boxes). Although researchers and other adults are rightfully concerned about these disparities, it is important not to buy into deficit assumptions, where researchers assume that children and youth at the bottom of these status hierarchies (i.e., females and those with minority gender identities and sexual orientations) are somehow “at risk,” “vulnerable,” or “less than.” We need to protect all children and youth from social contextual conditions that are dangerous for their development, but just like youth from ethnic and racial minorities, youth from sexual and gender minorities generally grow up whole, healthy, and resilient.

Optional Reading:

In this brief article, authors Leaper and Brown (2018) summarize findings on the impact that gender–and specifically gender roles, stereotypes, and discrimination–have on children’s development. In three sections (beginning on page 2), their paper reviews recent research on how these factors impact development in areas of gender identity and expression, academic achievement, and harassment, respectively.

Note: There is some disagreement among researchers on the exact meaning of the term “sexism.” The authors of this paper use the term “sexism” to refer to gender roles, stereotypes, discrimination, biases (positive and negative), and gender differences, as well as general beliefs, cognitions, and expectations about gender. We prefer the more-common usage of “sexism” as referring to gender discrimination in line with the status hierarchy defined above (i.e. with women and LGBTQ individuals at the bottom), that gender discrimination refers to any discrimination on the basis of gender (e.g. against men or women), and although concepts such as gender roles and gender cognitions are related to sexism, they are distinct ideas and better referred to with more precise terms.

Discrimination based on Sexual Orientation. The United States is heteronormative, meaning that society supports heterosexuality as the norm. Consider, for example, that homosexuals are often asked, “When did you know you were gay?” but heterosexuals are rarely asked, “When did you know you were straight?” (Ryle, 2011). Living in a culture that privileges heterosexuality has a significant impact on the ways in which non-heterosexual people are able to develop and express their sexuality.

Open identification of one’s sexual orientation may be hindered by homophobia which encompasses a range of negative attitudes and stereotypes toward homosexuality or people who are identified or perceived as being lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT). It can be expressed as antipathy, contempt, prejudice, aversion, or hatred; it may be based on irrational fear and is sometimes related to religious beliefs (Carroll, 2016). Homophobia is observable in critical and hostile behavior, such as discrimination and violence on the basis of sexual orientations that are non-heterosexual. Recognized types of homophobia include institutionalized homophobia, such as religious and state-sponsored homophobia, and internalized homophobia in which people with same-sex attractions internalize, or believe, society’s negative views and/or hatred of themselves.

Sexual minorities regularly experience stigma, harassment, discrimination, and violence based on their sexual orientation (Carroll, 2016). Research has shown that gay, lesbian, and bisexual teenagers are at a higher risk of depression and suicide due to exclusion from social groups, rejection from peers and family, and negative media portrayals of homosexuals (Bauermeister et al., 2010). Discrimination can occur in the workplace, in housing, at schools, and in numerous public settings. Major policies to prevent discrimination based on sexual orientation have only come into effect in the United States in the last few years.

The majority of empirical and clinical research on LGBT populations are done with largely white, middle-class, well-educated samples. This demographic limits our understanding of more marginalized sub-populations that are also affected by racism, classism, and other forms of oppression. In the United States, non-Caucasian LGBT individuals may find themselves in a double minority, in which they are not fully accepted or understood by Caucasian LGBT communities and are also not accepted by their own ethnic group (Tye, 2006). Many people experience racism in in the dominant LGBT community where racial stereotypes merge with gender stereotypes.

Discrimination based on Gender Minority status. Gender nonconforming people are much more likely to experience harassment, bullying, and violence based on their gender identity; they also experience much higher rates of discrimination in housing, employment, healthcare, and education (Borgogna, McDermott, Aita, & Kridel, 2019; National Center for Transgender Equality, 2015). Transgender individuals of color face additional financial, social, and interpersonal challenges, in comparison to the transgender community as a whole, as a result of structural racism. Black transgender people reported the highest level of discrimination among all transgender individuals of color. As members of several intersecting minority groups, transgender people of color, and transgender women of color in particular, are especially vulnerable to employment discrimination, health disparities, harassment, and violence. Consequently, they face even greater obstacles than white transgender individuals and cisgender members of their own race.

Effects of Gender Minority Discrimination on Mental Health. Using data from over 43,000 college students, Borgona et al. (2019) examined mental health disparities among several gender groups, including those identifying as cisgender, transgender, and gender nonconforming. Results indicated that participants who identified as transgender and gender nonconforming had significantly higher levels of anxiety and depression than those identifying as cisgender. Bargona et al. explained the higher rates of anxiety and depression using the minority stress model, which holds that an unaccepting social environment results in both external and internal stress which can take a toll on mental health. External stressors include discrimination, harassment, and prejudice, while internal stressors include negative thoughts, feelings and emotions resulting from societal messages about one’s identity. Borgona et al. recommend that mental health services be made accessible that are sensitive to both gender minority and sexual minority status.

How do we create gender-affirming social contexts for children and youth?

Starting at birth, children learn the social meanings of gender from their society and culture. Gender roles and expectations are especially portrayed in children’s toys, books, commercials, video games, movies, television shows and music (Knorr, 2017). Therefore, when children make choices regarding their gender identification, expression, or behavior that do not conform to gender stereotypes, it is important that they feel supported by the caring adults in their lives. This support allows children to feel valued, resilient, and develop a secure sense of self (American Academy of Pediatricians, 2015). People who care about the healthy gender development of children and youth, like their parents, families, friends, classmates, schools, and communities, can create local contexts of celebration and validation that allow all children to form complex and multifaceted gender identities. Collective social movements around LGBTQ+ and women’s rights are having many positive effects in changing current status hierarchies, which will result in social contextual conditions that are better for all our development.

Developmental psychologists, psychiatrists, and pediatricians can play important roles in creating gender-affirming support for children, youth, and families. For example, in a recent paper on the development of transgender youth, Diamond (2020) points out that, “physicians’ and psychologists’ lack of knowledge about transgender and nonbinary identities can be a significant barrier to competent care (American Psychological Association, 2015). Current practice guidelines for both the medical and psychological treatment of transgender youth adopt a gender-affirmative model of care, which views gender variation as a basic form of human diversity rather than an inherent pathology, and which takes a multifaceted approach to supporting and affirming youth’s experienced gender identity and reducing psychological distress… Providing youth—and parents—with more time, support, and information about the full range of gender diversity, and the fact that gender expressions and identities may change dynamically across different stages of development, may help facilitate more effective decisions about social and medical transitions” (p.112).

Developmental researchers can also make contributions by continuing to explore these complex issues. For example, few studies have been conducted to date, and so more research is needed, on the development of ingroup/outgroup biases (preferences for one’s own gender), reactions to gender norm violations, awareness of preferential treatment, gender prejudice and discrimination, and bullying based on gender variation (Martin & Ruble, 2010). Interventionists can work to identify the conditions that promote healthy gender and sexual development. Such studies have shown, for example, the beneficial effects of inclusive sex education programs in school that foster awareness and acceptance of gender diversity. As Diamond (2020) concludes, “studies suggest that the most beneficial intervention approaches involve creating safe and supportive spaces for all youth to give voice to diverse experiences of gender identity and expression; educating peers, schools, communities, and families about the validity of transgender and nonbinary identities; and providing youth with access to supportive and informed care… In light of the complexity of adolescent gender variation, the best course of action for all youth might involve expanding the gender-affirmative model beyond the conventional gender binary, thereby providing a broader range of options for identity and expression, and affirming and supporting the experiences of youth with complex, nonbinary identities… Whether a child identifies as male, female, transgender, gender fluid, or nonbinary, environments that foster self-acceptance, validation, openness, broadmindedness, and support regarding gender expression will yield lasting benefits.” (p. 113)

Optional Reading: