Death, Dying, & Bereavement

The last phase of the lifespan includes death and dying. Most other developments across the rest of the lifespan represent sets of options, but this last step is not optional. It is where all our earthly journeys end. In this chapter, we explain differences in life expectancy and the factors that influence length of life, as well as theories of aging itself. We consider the end of life and how it is approached in different cultures. We examine the ways that conceptions of death differ and develop across childhood and adolescence, as well as processes of grief and bereavement and the factors that influence how they unfold and are resolved.

Lifespan and Life Expectancy: Healthy Aging

Life Expectancy vs. Lifespan

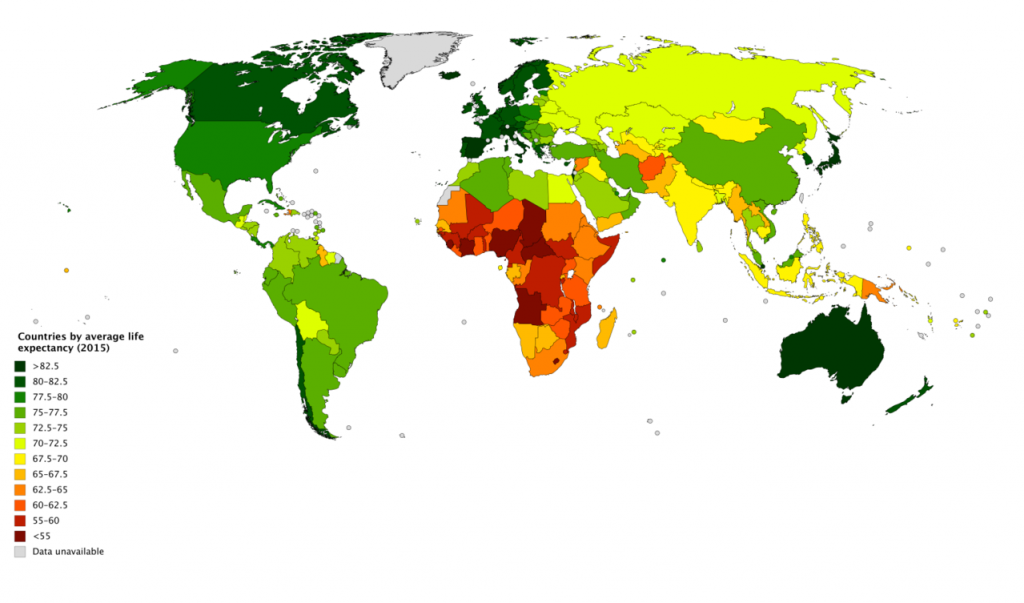

Lifespan or maximum lifespan refer to the greatest age reached by any member of a given species (or population). For humans, the lifespan is currently between 120 and 125. Life expectancy is defined as the average number of years that members of a species (or population) live. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) (2019) global life expectancy for those born in 2019 is 72.0 years, with females reaching 74.2 years and males reaching 69.8 years. Women live longer than men around the world, and the gap between the sexes has remained the same since 1990. Overall life expectancy ranges from 61.2 years in the WHO African Region to 77.5 years in the WHO European Region. Global life expectancy increased by 5.5 years between 2000 and 2016. Improvements in child survival and access to antiretroviral medication for the treatment of HIV are considered the main reasons for this increase. However, life expectancy in low-income countries (62.7 years) is 18.1 years lower than in high-income countries (80.8 years). In high-income countries, the majority of people who die are old, while in low-income countries almost one in three deaths are in children under 5 years of age. According to the Central Intelligence Agency (2019) the United States ranks 45th in the world for life expectancy.

World Healthy Life Expectancy. A better way to appreciate the diversity of people in late adulthood is to go beyond chronological age and examine how well the person is aging. Many in late adulthood enjoy better than average health and social well-being and so are aging at an optimal level. In contrast, others experience poor health and dependence to a greater extent than would be considered typical. When looking at large populations, the WHO (2019) measures how many equivalent years of full health on average a newborn baby is expected to have. This age, called The Healthy Life Expectancy, takes into account current age-specific mortality, morbidity, and disability risks. In 2016, the global Healthy Life Expectancy was 63.3 years up from 58.5 years in 2000. The WHO African Region had the lowest Healthy Life Expectancy at 53.8 years, while the WHO Western Pacific Region had the highest at 68.9 years.

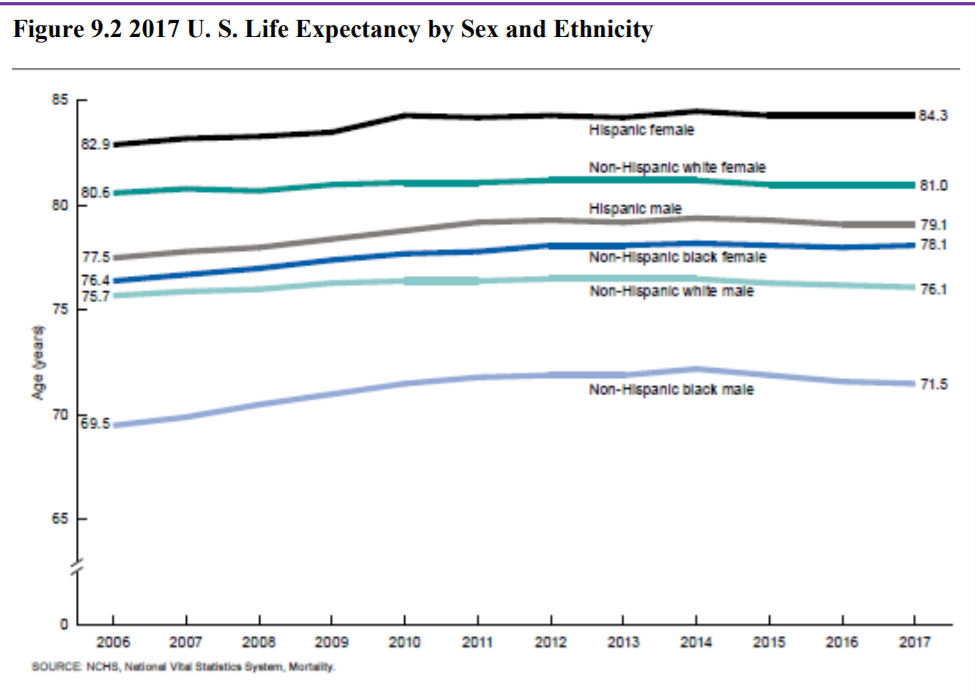

Life Expectancy in America. The overall life expectancy for a baby born in 2017 in the United States is 78.6 years, decreasing from 78.7 years in 2016 and 78.8 years in 2015 (Arias & Xu, 2019). The decrease from 2016 occurred for males, changing from 76.2 years to 76.1 years, while it did not change for females (81.1 years). Life expectancy at birth decreased by 0.1 year for the non-Hispanic white population (78.6 to 78.5). Life expectancy at birth did not change from 2016 for the non-Hispanic black population (74.9), and the Hispanic population (81.8). Before this unprecedented two-year decline, life expectancy had been increasing steadily for decades. Reasons given by the CDC for this decrease in life expectancy include deaths from drug overdoses, an increase in liver disease, and a rise in suicide rates (Saiidi, 2019). Figure 10.18 shows the United States life expectancy from 2006-2017 by ethnicity and sex.

American Healthy Life Expectancy. To determine the current United States Healthy Life Expectancy (HLE), factors were evaluated in 2007-2009 to determine how long an individual currently at age 65 will continue to experience good health (CDC, 2013). The highest Healthy Life Expectancy (HLE) was observed in Hawaii with 16.2 years of additional good health, and the lowest was in Mississippi with only 10.8 years of additional good health. Overall, the lowest HLE was among southern states. Females had a greater HLE than males at age 65 years in every state and DC. HLE was greater for whites than for blacks in DC and all states from which data were available, except in Nevada and New Mexico.

BLUE ZONES

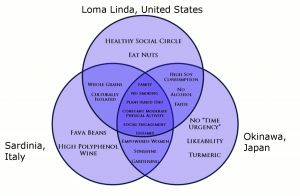

Recent research on longevity reveals that people in some regions of the world live significantly longer than people elsewhere. Efforts to study the common factors between these areas and the people who live there is known as blue zone research. Blue zones are regions of the world where Dan Buettner claims people live much longer than average. The term first appeared in his November 2005 National Geographic magazine cover story, “The Secrets of a Long Life.” Buettner identified five regions as “Blue Zones”: Okinawa (Japan); Sardinia (Italy); Nicoya (Costa Rica); Icaria (Greece); and the Seventh-day Adventists in Loma Linda, California. He offers an explanation, based on data and first hand observations, for why these populations live healthier and longer lives than others.

The people inhabiting blue zones share common lifestyle characteristics that contribute to their longevity. The Venn diagram below (Figure 10.19) highlights the following six shared characteristics among the people of Okinawa, Sardinia, and Loma Linda blue zones. Though not a lifestyle choice, they also live as isolated populations with a related gene pool.

- Family – put ahead of other concerns

- Less smoking

- Semi-vegetarianism – the majority of food consumed is derived from plants

- Legumes commonly consumed

- Constant moderate physical activity – an inseparable part of life

- Social engagement – people of all ages are socially active and integrated into their communities

In his book, Buettner provides a list of nine lessons, covering the lifestyle of blue zones people:

- Moderate, regular physical activity.

- Life purpose.

- Stress reduction.

- Moderate caloric intake.

- Plant-based diet.

- Moderate alcohol intake, especially wine.

- Engagement in spirituality or religion.

- Engagement in family life.

- Engagement in social life.

Figure 10.19. Blue zones share many common healthy habits

contributing to longer lifespans.

Although improvements have occurred in overall life expectancy, children born in America today may be the first generation to have a shorter life span than their parents. Much of this decline has been attributed to the increase in sedentary lifestyle and obesity. Since 1980, the obesity rate for children between the ages of 2 and 19 has tripled, as 20.5% of children were obese in 2014 compared with 5% in 1980 (American Medical Association, 2016). Obesity in children is associated with many health problems, including high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, elevated blood cholesterol levels, and psychological concerns including low self-esteem, negative body image, and depression. Excess weight is associated with an earlier risk of obesity-related diseases and death. In 2007, former Surgeon General Richard Carmona stated, “Because of the increasing rates of obesity, unhealthy eating habits and physical inactivity, we may see the first generation that will be less healthy and have a shorter life expectancy than their parents” (p. 1).

Gender Differences in Life Expectancy

Several explanations have been offered for the gender differences in average life expectancy that emerged in the late 1800s– one focused on nature and the other on nurture.

Biological Explanations. Biological differences in sex chromosomes and different pattern of gene expression are theorized as one reason why females live longer (Chmielewski, Boryslawski, & Strzelec, 2016). Males are heterogametic (XY), whereas females are homogametic (XX) with respect to sex chromosomes. Males can only express the X chromosome genes that come from the mother, while females have the advantage of being able to select the “better” X chromosome from their mother or father, while inactivating the “worse” X chromosome. This process of selection for “better” genes is impossible in males and results in the greater genetic and developmental stability of females.

In terms of developmental biology, women are the “default” sex, which means that the creation of a male individual requires a sequence of events at a molecular level. According to Chmilewski et al. (2016), these events are initiated by the activity of the SRY gene located on the Y chromosome. This activity and change in the direction of development results in a greater number of disturbances and developmental disorders, because the normal course of development requires many different factors and mechanisms, each of which must work properly and at a specific stage of the development (p. 134).

Men are more likely to contract viral and bacterial infections, and their immunity at the cellular level decreases significantly faster with age. Although women are slightly more prone to autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, the gradual deterioration of the immune system is slower in women (Caruso, Accardi, Virruso, & Candore, 2013; Hirokawa et al., 2013).

Looking at the influence of hormones, estrogen levels in women appear to have a protective effect on their heart and circulatory systems (Viña, Borrás, Gambini, Sastre, & Pallardó, 2005). Estrogens also have antioxidant properties that protect against harmful effects of free radicals, which damage cell components, cause mutations, and are in part responsible for the aging process. Testosterone levels are higher in men than in women and are related to more frequent cardiovascular and immune disorders. The level of testosterone is also responsible, in part, for male behavioral patterns, including increased level of aggression and violence (Martin, Poon, & Hagberg, 2011; Borysławski & Chmielewski, 2012).

Another factor responsible for risky behavior is the frontal lobe of the brain. The frontal lobe, which controls judgment and consideration of an action’s consequences, develops more slowly in boys and young men. This lack of judgment affects lifestyle choices, and consequently many more boys and men die by smoking, excessive drinking, accidents, drunk driving, and violence (Shmerling, 2016).

Lifestyle Factors. Certainly not all the reasons women live longer than men are biological. As previously mentioned, male behavioral patterns and lifestyle play a significant role in the shorter lifespans for males. One significant factor is that males work in more dangerous jobs, including police, fire fighters, and construction, and they are more exposed to violence. According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (2014) there were 11,961 homicides in the U.S. in 2014 (last year for full data) and of those 77% were males. Further, males serve in the military in much larger numbers than females. According to the Department of Defense (2015), in 2014 83% of all officers in the Services (Navy, Army, Marine Corps and Air Force) were male, while 85% of all enlisted service members were male. Males are also more than three times as likely to commit suicide (CDC, 2016a).

Additionally, men are less likely than women to have health insurance, develop a regular relationship with a doctor, or seek treatment for a medical condition (Scott, 2015). As mentioned in the middle adulthood chapter, women are more religious than men, which is associated with healthier behaviors (Greenfield, Vaillant & Marks, 2009). Lastly, social contact is also important as loneliness is considered a health hazard. Nearly 20% of men over 50 have contact with their friends less than once a month, compared to only 12% of women who see friends that infrequently (Scott, 2015). Hence, men’s lower life expectancy appears to be due to both biological and lifestyle factors.

Theories of Aging

Why do we age? There are many theories that attempt to explain how we age, but researchers still do not fully understand what factors contribute to the human lifespan (Jin, 2010). Research on aging is constantly evolving and includes a variety of studies involving genetics, biochemistry, animal models, and human longitudinal studies (NIA, 2011a). According to Jin (2010), modern biological theories of human aging involve two categories. The first is Programmed Theories that follow a biological timetable, possibly a continuation of childhood development. This timetable would depend on “changes in gene expression that affect the systems responsible for maintenance, repair, and defense responses,” (p. 72). The second category includes Damage Theories which emphasize environmental factors that cause cumulative damage in organisms. Examples from each of these categories will be discussed.

Primary Aging: Programmed Theories

Genetics. Genetic make-up certainly plays a role in longevity, but scientists are still attempting to identify which genes are responsible. Based on animal models, some genes promote longer life, while other genes limit longevity.

Specifically, longevity may be due to genes that better equip someone to survive a disease. For others, some genes may accelerate the rate of aging, while others slow that rate. To help determine which genes promote longevity and how they operate, researchers scan the entire genome and compare genetic variants in those who live longer with those who have an average or shorter lifespan. For example, a National Institutes of Health study identified genes possibly associated with blood fat levels and cholesterol, both risk factors for coronary disease and early death (NIA, 2011a). Researchers believe that it is most likely a combination of many genes that affect the rate of aging.

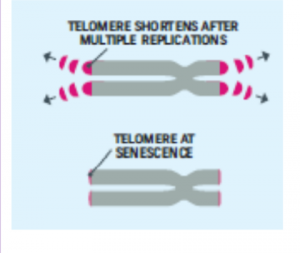

Cellular Clock Theory. This theory suggests that biological aging is due to the fact that normal cells cannot divide indefinitely. This is known as the Hayflick limit, and is evidenced in cells studied in test tubes, which divide about 40-60 times before they stop (Bartlett, 2014). But what is the mechanism behind this cellular senescence? At the end of each chromosomal strand is a sequence of DNA that does not code for any particular protein, but protects the rest of the chromosome, which is called a telomere.

With each replication, the telomere gets shorter. Once it becomes too short the cell does one of three things. It can stop replicating by turning itself off, called cellular senescence. It can stop replicating by dying, called apoptosis. Or, as in the development of cancer, it can continue to divide and become abnormal. Senescent cells can also create problems. While they may be turned off, they are not dead, thus they still interact with other cells in the body and can lead to an increase risk of disease. When we are young, senescent cells may reduce our risk of serious diseases such as cancer, but as we age they increase our risk of such problems (NIA, 2011a). The question of why cellular senescence changes from being beneficial to being detrimental is still under investigation. The answer may lead to some important clues about the aging process.

DNA Damage. Over time DNA, which contains the genetic code for all organisms, accumulates damage. This is usually not a concern as our cells are capable of repairing damage throughout our life. Further, some damage is harmless. However, some damage cannot be repaired and remains in our DNA. Scientists believe that this damage, and the body’s inability to fix itself, is an important part of aging (NIA, 2011a). As DNA damage accumulates with increasing age, it can cause cells to deteriorate and malfunction (Jin, 2010). Factors that can damage DNA include ultraviolet radiation, cigarette smoking, and exposure to hydrocarbons, such as auto exhaust and coal (Dollemore, 2006).

Mitochondrial Damage. Damage to mitochondrial DNA can lead to a decaying of the mitochondria, which is a cell organelle that uses oxygen to produce energy from food. The mitochondria convert oxygen to adenosine triphosphate (ATP) which provides the energy for the cell. When damaged, mitochondria become less efficient and generate less energy for the cell and can lead to cellular death (NIA, 2011a).

Free Radicals. When the mitochondria use oxygen to produce energy, they also produce potentially harmful byproducts called oxygen free radicals (NIA, 2011a). The free radicals are missing an electron and create instability in surrounding molecules by taking electrons from them. There is a snowball effect (A takes from B and then B takes from C, etc.) that creates more free radicals which disrupt the cell and causes it to behave abnormally (See Figure 10.22). Some free radicals are helpful as they can destroy bacteria and other harmful organisms, but for the most part they cause damage in our cells and tissue. Free radicals are identified with disorders seen in those of advanced age, including cancer, atherosclerosis, cataracts, and neurodegeneration. Some research has suggested that adding antioxidants to our diets can help counter the effects of free radical damage because the antioxidants can donate an electron that can neutralize damaged molecules. However, the research on the effectiveness of antioxidants is not conclusive (Harvard School of Public Health, 2016).

Immune and Hormonal Stress Theories. Ever notice how quickly U.S. presidents seem to age? Before and after photos reveal how stress can play a role in the aging process. When gerontologists study stress, they are not just considering major life events, such as unemployment, death of a loved one, or the birth of a child. They are also including metabolic stress, the life sustaining activities of the body, such as circulating the blood, eliminating waste, controlling body temperature, and neuronal firing in the brain. In other words, all the activities that keep the body alive also create biological stress.

To understand how this stress affects aging, researchers note that both problems with the innate and adaptive immune system play key roles. The innate immune system is made up of the skin, mucous membranes, cough reflex, stomach acid, and specialized cells that alert the body of an impending threat. With age these cells lose their ability to communicate as effectively, making it harder for the body to mobilize its defenses. The adaptive immune system includes the tonsils, spleen, bone marrow, thymus, circulatory system and the lymphatic system that work to produce and transport T cells. T-cells, or lymphocytes, fight bacteria, viruses, and other foreign threats to the body. T-cells are in a “naïve” state before they are programmed to fight an invader and become “memory cells”. These cells now remember how to fight a certain infection should the body ever come across this invader again. Memory cells can remain in your body for many decades, which is why the measles vaccine you received as a child is still protecting you from this virus today. As older adults produce fewer new T-cells to be programmed, they are less able to fight off new threats and new vaccines work less effectively. The reason why the shingles vaccine works well with older adults is because they already have some existing memory cells against the varicella virus. The shingles vaccine is acting as a booster (NIA, 2011a).

Hormonal Stress Theory, also known as Neuroendocrine Theory of Aging, suggests that as we age the ability of the hypothalamus to regulate hormones in the body begins to decline leading to metabolic problems (American Federation of Aging Research (AFAR) 2011). This decline is linked to excessive levels of the stress hormone cortisol. While many of the body’s hormones decrease with age, cortisol does not (NIH, 2014a). The more stress we experience, the more cortisol we release, and the more hypothalamic damage that occurs. Changes in hormones have been linked to several metabolic and hormone related problems that increase with age, such as diabetes (AFAR, 2011), thyroid problems (NIH, 2013), osteoporosis, and orthostatic hypotension (NIH, 2014a).

Secondary Aging: Damage Theories

A second set of theories focuses on aging as an outcome of the wear and tear our bodies receive as part of our daily lives. Damage theories examine the parts of aging and death that come from the outside. This perspective scrutinizes the nurture or environmental side of the equation, and holds that the body wears out through the cumulative effects of a host of life events and lifestyle factors, such as disease, disuse, abuse, stress, and environmental toxins. Evidence to support this position comes from three sources.

Lifestyle Factors that Predict Aging and Death. The first body of research supporting the role of nurture in aging examines the effects of a variety of physical factors, such as poor diet, lack of exercise, and substance abuse, as well as psychological factors, such as stress, social inactivity, and pessimistic outlook. Studies show that these factors can predict both how healthy people will be and how long they will live. Such forces can cause biological damage, which is repaired more and more slowly as we age. From this perspective aging results from the accumulation of such damage.

Exposure to Environmental Toxins. A second body of evidence shows that aging can be shaped by exposure to environmental pollution, as caused for example by pesticides, air pollutants, and radiation, or by harmful substances added to our food and water. When we metabolize these toxins, they do damage, not only to our bodies, but also to our our genetic DNA material at the cellular level. As our organ systems deteriorate and become more vulnerable, errors pile up- and our body’s ability to repair them slows down. Toxins can cause allergic reactions and auto-immune diseases, as seen in the upswing in Type II adult-onset diabetes and other chronic conditions. Effects of environmental toxins are also seen in inflammatory processes involved in life threatening medical conditions, like cardiovascular disease, arthritis, and cancer.

Historical Increases in Average Life Expectancy. A third source of evidence that aging can be speeded up or slowed down by external factors comes from documentation of steady historical increases in average life expectancy. These increases follow from changes in external factors, mostly related to public health. They include historical reductions in the number of people in extreme poverty as well as improvements in nutrition, quality and access to medical care, sanitation, child birth procedures, and the invention of antibiotics. These historical changes did not result in evolutionary changes in human biology. They produced recent changes in environmental factors that are shaping the rate of aging and the timing of death.

In sum, as you can see that aging and death are processes that are multiply determined– by biological, psychological, social, and contextual factors. Theories of primary aging are correct that we have the seeds of our aging programmed into our bodies. But theories of secondary aging are also correct– the environment also speeds-up and slows down our aging and dying via the damage it does to our increasingly vulnerable biology. And, of course, lifespan researchers would remind us that the active individual also plays a role through the decisions they make about behavioral risks, like smoking, drinking, and using or abusing substances, as well as via more positive routes, especially a healthy diet, exercise, and continued participation in positive social and cognitive activities.

Dying and Grieving in Children and Adolescents: Developmental Concepts of Death

When we think of death and dying, we naturally focus on the elderly, and when we think of children in this process, we typically think of adult children, who often act as caregivers for their aging and dying parents. However, children and adolescents are also involved in both dying and bereavement. An understanding of age-appropriate grief reactions and conceptions of death are important when assessing a child’s response to their own terminal illness and how they are dealing with the death of a loved one. This section reviews key developmental concepts and describes strategies for supporting children and adolescents who are grieving as well as those who are dying.

Children grieve differently than adults. They often grieve in spurts and can re-grieve at new developmental stages as their understanding of death and perceptions of the world change. Childhood grief may be expressed as behavioral changes and/or emotional expression. The two most important predictive factors of a child’s successful resolution after suffering a loss are the availability of one significant adult and the provision of a safe physical and emotional environment.

Dying and Grieving during Infancy (0-2 years)

Children at this age have no cognitive understanding of death. If they themselves are dying, they are not aware of this fact. Their reactions are based completely on local conditions, including their contact with caregivers and their own current levels of pain and suffering. Infants can be comforted by the presence of secure attachment figures and palliative care to reduce pain. The process of dying is much more psychologically painful for caregivers than for infants, but hospitals and hospice care know how important the active participation of a caring and responsive attachment figure can be, one who is making medical decisions based on the balance between the probability that a treatment will be effective (vs. prolong the dying process) and the pain that treatments cause.

In terms of infants’ reactions to the death of a loved one, even if infants are not cognitively aware of death, they are cognizant of separation and loss, and so separation anxiety and grief reactions are possible. Behavioral and developmental regression can occur as children have difficulty identifying and dealing with their loss; they may react in concert with the distress experienced by their caregiver. There is a need to maintain routines and to avoid separation from significant others.

If the death is the primary attachment figure, the presence of grief and the severity of the infant’s reaction will depend on their age and the quality of care they receive from their new primary caregiver. Before the age of 6 months, the long term effects of maternal death depend almost entirely on whether a sensitive responsive substitute caregiver can be found who can take over immediately. For children older than 6 months, who have formed a specific attachment to the primary caregiver, expressions of grief and loss are common, but the transition is easier if the new primary caregiver is someone who the infant or toddler knows and with whom they already have a trusting relationship (e.g., father, aunt, grandmother). As mentioned previously, children may repeatedly revisit and re-grieve the loss of a primary caregiver at successive ages as they develop cognitive capacities that allow them to to reflect on the loss in qualitatively different ways.

Dying and Grieving during Early Childhood (2-6 years)

Preschool age children see death as temporary and reversible. They interpret their world in a literal manner and may ask questions reflecting this perspective. When children themselves are facing death, they take their cues about what is happening almost entirely from their caregivers and the other people around them. They have typical developmentally-graded concerns about attachment and abandonment, and have a hard time understanding why they have to accept painful treatments and why they can’t just go home and get back to life as usual. They can have tantrums and difficulty regulating their emotions and behaviors, and it can be hard for parents to discipline or set limits with a terminally ill child. However, the same kinds of high quality parenting that are good for children in other circumstances, namely, love (affection, caring, and concern) combined with firm and reasonable limits, and autonomy support (validation and opportunities for free expression of preferences and perspectives), are helpful for young children in these situations. Young children should be protected from adult anguish, but they can sense when adults are upset. Small children benefit from familiar routines, assurances that familiar adults are going to be with them the whole time, support for whatever emotions children are actually experiencing, and developmentally-attuned explanations and answers to young children’s questions.

When preschool aged children are dealing with the death of a loved one, especially a central person in their lives, like a mother, father, or sibling, their conception of death makes the process of grieving more difficult. They may believe that death can be caused by thoughts and provide magical explanations, often blaming themselves for the death. The conviction that death is reversible makes it difficult for preschoolers to cognitively accept the death as final. They sometimes beg parents to go get the dead person and bring them back home, and they can become frantic if they are told that the person has been buried. In the context of this conception of death, it is challenging to provide simple and straightforward explanations that emphasize that the child is not to blame, that the loved one cannot return even though they did not want to go, and that the absent person still loves the child.

Even when adults avoid euphemisms and try to correct misperceptions, preschool children often regard death like a kidnapping (with the dead person taken far away against their will) until they reach the concrete operational stage of cognitive development, when they rework their understanding of the death. It is this combination of developmental characteristics– when a young child has a full-blown attachment to a primary caregiver and a conception of death that makes it impossible to accept death as final– that puts children this age at particular risk for complicated grief and long-term negative neurophysiological and psychological effects. As with infants, the greatest protection against developmental risk is provided by the immediate presence of a loving and stable attachment figure, preferably one to whom the young child is already securely attached.

Dying and Grieving during the Stage of Concrete Operational Development

Middle childhood (6-8 years). When children reach the concrete operational stage of cognitive development, they understand that death is final and irreversible but do not believe that it is universal or could happen to them. Death is often personalized and/or personified. Expressions of anger towards the deceased or towards those perceived to have been unable to save the deceased can occur. Anxiety, depressive symptoms, and somatic complaints may be present. The child often has fears about death and concerns about the safety of their other loved ones. In addition to giving clear, realistic information, offer to include the child in funeral ceremonies. Notifying the school will help teachers understand the child’s reaction and provide additional adult support.

Preadolescence (8-12 years). Children at this age have an adult understanding of death – that it is final, irreversible, and universal. They are able to understand the biological aspects of death as well as cause-and-effect relationships. They tend to intellectualize death as many have not yet learned to identify and deal with feelings. They may develop a morbid curiosity and are often interested in the physical details of the dying process as well as religious and cultural traditions surrounding death. The ability to identify causal relationships can lead to feelings of guilt; such feelings should be explored and addressed. To facilitate identification with emotions, it may prove useful to talk about your own emotions surrounding death and to offer opportunities for the child to discuss death. The child should also be allowed to participate, as much as they feel comfortable, in seeing the dying patient and participating in activities surrounding the death.

During middle childhood and preadolescence, children have a concrete operational understanding of death. When children in this stage are themselves terminally ill and facing their own death, their concrete understanding of death can lead to a relatively matter-of-fact acknowledgement of the actual situation. At this age, adults should still follow the child’s lead in terms of questions and explanations, and share their own grief and sadness only as appropriate. Children may show a wide variety of emotions, but they still have developmentally-graded concerns focused, for example, on keeping up with their friends and their schoolwork. To the extent that the parents of a child’s friends are willing to let them keep the dying child company, the presence of friends can provide both distraction and comfort to the child. Connections with friends can also be maintained through letters, notes, phone conversations, and virtual meetings, where the friends can play games or work together on their homework.

Dying and Grieving during Adolescence (12-18 years)

Adolescents also have an adult understanding of death. At the same time, however, they are also developing the ability to think abstractly and are often curious of the existential implications of death. They often reject adult rituals and support and feel that no one understands them. They may engage in high-risk activities in order to more fully challenge their own mortality. They often have strong emotional reactions and may have difficulty identifying and expressing feelings. It is important that adults support independence and access to peers, but also provide emotional support when needed.

When adolescents face their own deaths, they also have full blown emotional and psychological reactions. Like adults, they can grieve the lives and possibilities that are lost with death at a young age. Parents and peers can help them create legacy projects, like blogs, videos, music, or books, that can enable adolescents to feel that they have accomplished at least some parts of their life purposes. However, they remain adolescents, with developmentally-appropriate concerns and problems. For example, the emotional instability and need for autonomy that is characteristic of adolescence can sometimes make it difficult for parents to provide helpful support under such circumstances. Adolescents can get into arguments with parents about whether or not they will accept certain medical treatments, especially if the treatments affect their physical appearance. Adolescents, especially young adolescents, can find life-threatening diseases embarrassing, because it makes them different from their peers during a time when they are concerned with peer conformity. However, adults can rest assured that even if they do not always acknowledge it, adolescents count on the presence, wisdom, and support of their parents.

In sum, the generalizations and strategies provided here only serve as a framework when helping a child come to terms with their own death or that of a loved one. The overarching message is that children and adolescents have age-graded conceptions of death, and developmentally-appropriate concerns and challenges in dealing with grieving and dying. They also need individually and developmentally attuned supports during these processes, which can be demanding for their adults. When in doubt, seek help from pediatricians, child-life specialists, mental health professionals, and others specializing in bereavement.

Loss during Childhood

Loss of a family member. For a child, the death of a parent, without support to manage the effects of the grief, may result in long-term psychological harm. This is more likely if adult caregivers are struggling with their own grief and are psychologically unavailable to the child. The surviving parent or caregiver plays a crucial role in helping the child adapt to a parent’s death. Studies have shown that losing a parent at a young age does not just lead to negative outcomes; there are also some potentially positive effects. Some children showed increased maturity, better coping, and improved communications skills. Adolescents who have lost a parent value other people more than those who have not experienced such a close loss (Ellis & Lloyd-Williams, 2008).

The loss of a parent, grandparent, or sibling can be very troubling in childhood, but even in childhood there are age differences in relation to the loss. A very young child, under six months of age, may have no reaction if a caregiver dies, but older children are typically affected by the loss. This is especially true if the loss occurs during the time when trust and dependency are formed. During critical periods such as 8–12 months, when attachment and separation anxiety are at their height, even a brief separation from a parent or other person who cares for the child can cause distress.

Even as a child grows older, death is still difficult to fathom and this affects how a child responds. For example, younger children see death more as a separation, and may believe death is curable or temporary. Reactions can manifest themselves in “acting out” behaviors: a return to earlier behaviors such as sucking thumbs, clinging to a toy or angry behavior; though they do not have the maturity to mourn as an adult, they feel the same intensity. As children enter pre-teen and teen years, there is a more mature understanding, but strong emotional reactions are still normal.

Loss of a friend or classmate. Children may experience the death of a friend or a classmate through illness, accidents, suicide, or violence. Loss from sudden violence, like drive by or school shootings, are particularly traumatic. Initial support involves reassuring children that they are safe, that their emotional and physical feelings are normal, and that support is available. Schools are advised to plan for these possibilities in advance. Planning and participating in rituals and memorials may be helpful, but will also challenging. Some children choose to continue visiting with the parents or family of their dead friend or classmate, to keep the connection, share the loss, and comfort the family.

Other forms of loss. Children can experience grief as a result of losses due to causes other than death. For example, children may grieve losses connected with divorce and pine for the original family that has been forever lost. As with other losses, they may re-grieve this transition as they get older and have more sophisticated cognitive capacities to reflect on and rework the meaning of the divorce. Relocations can also cause children significant grief particularly if they are combined with other difficult circumstances such as neglectful or abusive parental behaviors, other significant losses, etc. It is also possible for children who have been physically, psychologically, or sexually abused to grieve over the damage to or the loss of their ability to trust. Since such children usually have no support or acknowledgement from any source outside the family unit, this is likely to be experienced as disenfranchised grief.

End-of-Life

Kübler-Ross’ Stages of Loss

Based on her work and interviews with terminally ill patients, Kübler-Ross (1975) described five stages of loss experienced by someone who faces the news of their impending untimely death. These “stages” are not really stages that a person goes through in order or only once; nor are they stages that occur with the same intensity. Indeed, the process of death is influenced by a person’s life experiences, the timing of their death in relation to life events, the predictability of their death based on health or illness, their belief system, and their assessment of the quality of their own life. Nevertheless, these stages provide a framework to help us to understand and recognize some of what a dying person experiences psychologically. And by understanding, we are more equipped to support that person as they die and to face death ourselves when our time comes (Kübler-Ross, 1975).

Denial is often the first reaction to overwhelming, unimaginable news. Denial, or disbelief or shock, protects us by allowing such news to enter slowly and to give us time to come to grips with what is taking place. The person who receives positive test results for a life-threatening condition may question the diagnosis, seek second opinions, or may simply feel a sense of psychological disbelief even though they know that the results are true.

Anger also provides us with protection in that being angry energizes us to fight against something and gives structure to a situation that may be thrusting us into the unknown. It is much easier to be angry than to be sad or in pain or depressed. It helps us to temporarily believe that we have a sense of control over our future and to feel that we have at least expressed our rage about how unfair life can be. Anger can be focused on a person, a health care provider, at God, or at the world in general. And it can be expressed over issues that have nothing to do with our death; consequently, being in this stage of loss is not always obvious.

Bargaining involves trying to think of what could be done to turn the situation around. Living better, devoting oneself to a cause, being a better friend, parent, or spouse, are all agreements one might willingly commit to if doing so would lengthen life. Asking to just live long enough to witness a family event or finish a task are examples of bargaining.

Depression is sadness and sadness is appropriate for such an event. Feeling the full weight of loss, crying, and losing interest in the outside world is an important part of the process of dying. This depression makes others feel very uncomfortable and family members may try to console their loved one. Sometimes hospice care may include the use of antidepressants to reduce depression during this stage.

Acceptance involves learning how to carry on and to incorporate this aspect of the life span into daily existence. Reaching acceptance does not in any way imply that people who are dying are happy about it or content with it. It means that they are facing it and continuing to make arrangements and to say what they wish to say to others. Some terminally ill people find that they live life more fully than ever before after they come to this stage.

In some ways, these five stages serve as coping mechanisms, allowing the individual to make sense of the situation while coming to terms with what is happening. They are, in other words, the mind’s way of gradually recognizing the implications of one’s impending death and giving him or her the chance to process it. These stages provide a type of framework in which dying is experienced, although it is not exactly the same for every individual in every case. when death is on time and comes at the an advanced age, people have had more opportunity to come to grips with impending death and so may show only acceptance. In fact, research shows that as people age, they become less and less afraid of death, so that for many who are old-old (i.e., 85+ years), death seems like a natural next step.

Since Kübler-Ross presented these stages of loss, several other models have been developed. These subsequent models, in many ways, build on that of Kübler-Ross, offering expanded views of how individuals process loss and grief. While Kübler-Ross’ model was restricted to dying individuals, subsequent theories tended to focus on loss as a more general construct. This ultimately suggests that facing one’s own death is just one example of the grief and loss that human beings can experience, and that other loss or grief-related situations tend to be processed in a similar way.

Cultural Differences in End-of-Life Decisions

Cultural factors strongly influence how doctors, other health care providers, and family members communicate bad news to patients, the expectations regarding who makes the health care decisions, and attitudes about end-of-life care (Ganz, 2019; Searight & Gafford, 2005a). In Western medicine, doctors take the approach that patients should be told the truth about their health. Blank (2011) reports that 75% of the world’s population do not conduct medicine by the same standards. Thus, outside Western nations, and even among certain racial and ethnic groups within the those nations, doctors and family members may conceal the full nature of a terminal illness, as revealing such information is viewed as potentially harmful to the patient, or at the very least is seen as disrespectful and impolite. Chattopadhyay and Simon (2008) reported that in India doctors routinely abide by the family’s wishes and withhold information from the patient, while in Germany doctors are legally required to inform the patient. In addition, many doctors in Japan and in numerous African nations used terms such as “mass,” “growth,” and “unclean tissue” rather than referring to cancer when discussing the illness to patients and their families (Holland, Geary, Marchini, &Tross, 1987). Family members also actively protect terminally ill patients from knowing about their illness in many Hispanic, Chinese, and Pakistani cultures (Kaufert & Putsch, 1997; Herndon & Joyce, 2004).

In western medicine, we view the patient as autonomous in health care decisions (Chattopadhyay & Simon, 2008; Searight & Gafford, 2005a). However, in other nations the family or community plays the main role, or decisions are made primarily by medical professionals, or the doctors in concert with the family make the decisions for the patient. For instance, in comparison to European Americans and African Americans, Koreans and Mexican-Americans are more likely to view family members as the decision makers rather than just the patient (Berger, 1998; Searight & Gafford, 2005a). In many Asian cultures, illness is viewed as a “family event”, not just something that impacts the individual patient (Blank, 2011; Candib, 2002; Chattopadhyay & Simon, 2008). Thus, there is an expectation that the family has a say in the health care decisions. As many cultures attribute high regard and respect for doctors, patients and families may defer some of the end-of-life decision making to the medical professionals (Searight & Gafford, 2005b).

The notion of advanced directives, which spell out a patient’s wishes for end-of-life-care, hold little or no relevance in many cultures outside of western society (Blank, 2011). For instance, in India advanced directives are virtually non-existent, while in Germany they are regarded as a major part of health care (Chattopadhyay & Simon, 2008). Moreover, end-of-life decisions involve how much medical aid should be used. In the United States, Canada, and most European countries artificial feeding is more commonly used once a patient has stopped eating, while in many other nations lack of eating is seen as a sign, rather than a cause, of dying and do not consider using a feeding tube (Blank, 2011).

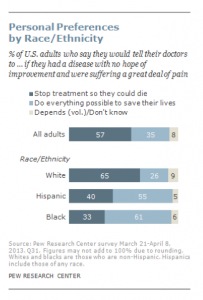

According to a Pew Research Center Survey (Lipka, 2014), while death may not be a comfortable topic to ponder, 37% of their survey respondents had given a great deal of thought about their end-of-life wishes, with 35% having put these in writing. Yet, over 25% had given no thought to this issue. Lipka (2014) also found that there were clear racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life wishes (see Figure 10.25). Whites are more likely than Blacks and Hispanics to prefer to have treatment stopped if they have a terminal illness. In contrast, the majority of Blacks (61%) and Hispanics (55%) prefer that everything be done to keep them alive. Searight and Gafford (2005a) suggest that the low rate of completion of advanced directives among non-whites may reflect a distrust of the U.S. health care system as a result of the health care disparities non-whites have experienced. Among Hispanics, patients may also be reluctant to select a single family member to be responsible for end-of-life decisions out of a concern of isolating the person named and of offending other family members, as this is commonly seen as a “family responsibility” (Morrison, Zayas, Mulvihill, Baskin, & Meier, 1998).

Religious Practices after Death

Funeral rites are expressions of loss that reflect personal and cultural beliefs about the meaning of death and the afterlife. Ceremonies provide survivors a sense of closure after a loss. These rites and ceremonies send the message that the death is real and allow friends and loved ones to express their love and respect for those who die. Under circumstances in which a person has been lost and presumed dead or when family members were unable to attend a funeral, there can continue to be a lack of closure that makes it difficult to grieve and to learn to live with loss. Although many people are still in shock when they attend funerals, the ceremony still provides a marker of the beginning of a new period of one’s life as a survivor. The following are some of the religious practices regarding death, however, individual religious interpretations and practices may occur (Dresser & Wasserman, 2010; Schechter, 2009).

Hinduism. The Hindu belief in reincarnation accelerates the funeral ritual, and deceased Hindus are cremated as soon as possible. After being washed, the body is anointed, dressed, and then placed on a stand decorated with flowers ready for cremation. Once the body has been cremated, the ashes are collected and, if possible, dispersed in one of India’s holy rivers.

Judaism. Among the Orthodox, the deceased is first washed and then wrapped in a simple white shroud. Males are also wrapped in their prayer shawls. Once shrouded the body is placed into a plain wooden coffin. The burial must occur as soon as possible after death, and a simple service consisting of prayers and a eulogy is given. After burial the family members typically gather in one home, often that of the deceased, and receive visitors. This is referred to as “sitting shiva”.

Muslim. In Islam the deceased are buried as soon as possible, and it is a requirement that the community be involved in the ritual. The individual is first washed and then wrapped in a plain white shroud called a kafan. Next, funeral prayers are said followed by the burial. The shrouded dead are placed directly in the earth without a casket and deep enough not to be disturbed. They are also positioned in the earth, on their right side, facing Mecca, Saudi Arabia.

Roman Catholic. Before death an ill Catholic individual is anointed by a priest, commonly referred to as the Anointing of the Sick. The priest recites a prayer and applies consecrated oil to the forehead and hands of the ill person. The individual also takes a final communion consisting of consecrated bread and wine. The funeral rites consist of three parts. First is the wake that usually occurs in a funeral parlor. The body is present, and prayers and eulogies are offered by family and friends. The funeral mass is next which includes an opening prayer, bible readings, liturgy, communion, and a concluding rite. The funeral then moves to the cemetery where a blessing of the grave, scripture reading, and prayers conclude the funeral ritual.

Green Burial

In 2017, the median cost of an adult funeral with viewing and burial was $8,775. The median cost for viewing and cremation was $6,260 (National Funeral Directors Association (NFDA), 2019). The same NFDA survey found that nearly half of all respondents had attended a funeral in a non-traditional setting, such as an outdoor setting that was meaningful to the deceased, and over half of the respondents said they would be interested in exploring green funeral options (NFDA, 2017).

According to the Green Burial Council (GBC) (2019) Americans bury over 64 thousand tons of steel, 17 thousand tons of copper and bronze, 1.6 million tons of concrete, 20 million feet of wood, and over 4 million gallons of embalming fluid every year. As a result, there has been a growing interest in green or natural burials. Green burials attempt to reduce the impact on the environment at every stage of the funeral. This can include using recycled paper, biodegradable caskets, cotton shroud in the place of any casket, formaldehyde free, or no embalming, and trying to maintain the natural environment around the burial site (GBC, 2019). According to the NFDA (2017), many cemeteries have reported that consumers are requesting green burial options, and since many of the add-ons of a traditional burial, such as a concrete vault, embalming, and casket are not required, the cost can be substantially less.

Optional Reading:

Curative, Palliative, and Hospice Care

When individuals become ill, they need to make choices about the treatment they wish to receive. One’s age, type of illness, and personal beliefs about dying affect the type of treatment chosen (Bell, 2010).

Curative care is designed to overcome and cure disease and illness (Fox, 1997). Its aim is to promote complete recovery, not just to reduce symptoms or pain. An example of curative care would be chemotherapy. While curing illness and disease is an important goal of medicine, it is not its only goal. As a result, some have criticized the curative model as ignoring the other goals of medicine, including preventing illness, restoring functional capacity, relieving suffering, and caring for those who cannot be cured.

Palliative care focuses on providing comfort and relief from physical and emotional pain to patients throughout their illness, even while being treated (NIH, 2007). In the past, palliative care was confined to offering comfort for the dying. Now it is offered whenever patients suffer from chronic illnesses, such as cancer or heart disease (IOM, 2015). Palliative care is also part of hospice programs.

Hospice emerged in the United Kingdom in the mid-20th century as a result of the work of Cicely Saunders. This approach became popularized in the U.S. by the work of Elizabeth Kübler-Ross (IOM, 2015), and by 2012 there were 5,500 hospice programs in the U.S. (National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO), 2013).

Hospice care whether at home, in a hospital, nursing home, or hospice facility involves a team of professionals and volunteers who provide terminally ill patients with medical, psychological, and spiritual support, along with support for their families (Shannon, 2006). The aim of hospice is to help the dying be as free from pain as possible, and to comfort both the patients and their families during a difficult time.

In order to enter hospice, a patient must be diagnosed as terminally ill with an anticipated death within 6 months (IOM, 2015). The patient is allowed to go through the dying process without invasive treatments. Hospice workers try to inform the family of what to expect and reassure them that much of what they see is a normal part of the dying process.

According to the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (2019) there are four types of hospice care in America:

- Routine hospice care, where the patient has chosen to receive hospice care at home, is the most common form of hospice.

- Continuous home care is predominantly nursing care, with caregiver and hospice aides supplementing this care, to manage pain and acute symptom crises for 8 to 24 hours in the home.

- Inpatient respite care is provided by a hospital, hospice, or long-term care facility to provide temporary relief for family caregivers.

- General inpatient care is provided by a hospital, hospice, or long-term care facility when pain and acute symptom management can on be handled in other settings.

In 2017, an estimated 1.5 million people residing in America received hospice care (NHPCO, 2019). The majority of patients on hospice were patients suffering from dementia, heart disease, or cancer, and typically did not enter hospice until the last few weeks prior to death. Almost one out of three patients were on hospice for less than a week.

According to Shannon (2006), the basic elements of hospice include:

- Care of the patient and family as a single unit

- Pain and symptom management for the patient

- Having access to day and night care

- Coordination of all medical services

- Social work, counseling, and pastoral services

- Bereavement counseling for the family up to one year after the patient’s death

Although hospice care has become more widespread, these new programs are subject to more rigorous insurance guidelines that dictate the types and amounts of medications used, length of stay, and types of patients who are eligible to receive hospice care (Weitz, 2007). Thus, more patients are being served, but providers have less control over the services they provide, and lengths of stay are more limited. In addition, a recent report by the Office of the Inspector General at U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2018) highlighted some of the vulnerabilities of the hospice system in the U.S. Among the concerns raised were that hospices did not always provide the care that was needed and sometimes the quality of that care was poor, even at Medicare certified facilities.

Not all racial and ethnic groups feel the same way about hospice care. African-American families may believe that medical treatment should be pursued on behalf of an ill relative as long as possible and that only God can decide when a person dies. Chinese-American families may feel very uncomfortable discussing issues of death or being near the deceased family member’s body. The view that hospice care should always be used is not held by everyone, and health care providers need to be sensitive to the wishes and beliefs of those they serve (Coolen, 2012).

Family Caregivers

According to the Institute of Medicine (2015), it is estimated that 66 million Americans, or 29% of the adult population, are caregivers for someone who is dying or chronically ill. Two-thirds of these caregivers are women. This care takes its toll physically, emotionally, and financially. Family caregivers may face the physical challenges of lifting, dressing, feeding, bathing, and transporting a dying or ill family member. They may worry about whether they are performing all tasks safely and properly, as they receive little training or guidance. Such caregiving tasks may also interfere with their ability to take care of themselves and meet other family and workplace obligations. Financially, families may face high out of pocket expenses (IOM, 2015).

As can be seen in Table 10.6, most family caregivers are providing care by themselves with little professional intervention, are employed, and have provided care for more than 3 years. The annual loss of productivity in the U.S. was $25 billion in 2013 as a result of work absenteeism due to providing this care. As the prevalence of chronic disease rises, the need for family caregivers is growing. Unfortunately, the number of potential family caregivers is declining as the large baby boomer generation enters into late adulthood (Redfoot, Feinberg, & Houser, 2013).

Table 10.6 Characteristics of Family Caregivers in the United States

| Characteristic | Percentages |

|---|---|

| No home visits by health care professionals | 69% |

| Caregivers are also employed | 72% |

| Duration of employed workers who have been caregiving for 3+ years | 55% |

| Caregivers for the elderly | 67% |

adapted from Lally & Valentine-French (2019) and IOM (2015)

Advanced Directives

Advanced care planning refers to all documents that pertain to end-of-life care. These include advance directives and medical orders. Advance directives include documents that mention a health care agent and living wills. These are initiated by the patient. Living wills are written or video statements that outline the health care initiates the person wishes under certain circumstances. Durable power of attorney for health care names the person who should make health care decisions in the event that the patient is incapacitated. In contrast, medical orders are crafted by a medical professional on behalf of a seriously ill patient. Unlike advanced directives, as these are doctor’s orders, they must be followed by other medical personnel. Medical orders include Physician Orders for Life-sustaining Treatment (POLST), do-not-resuscitate, do-not-incubate, or do-not-hospitalize. In some instances, medical orders may be limited to the facility in which they were written. Several states have endorsed POLST so that they are applicable across heath care settings (IOM, 2015).

Despite the fact that many Americans worry about the financial burden of end-of-life care, “more than one-quarter of all adults, including those aged 75 and older, have given little or no thought to their end-of-life wishes, and even fewer have captured those wishes in writing or through conversation” (IOM, 2015, p. 18).

Grief, Bereavement, and Mourning

The terms grief, bereavement, and mourning are often used interchangeably, however, they have different meanings. Grief is the normal process of reacting to a loss. Grief can be in response to a physical loss, such as a death, or a social loss including a relationship or job. Bereavement is the period after a loss during which grief and mourning occurs. The time spent in bereavement for the loss of a loved one depends on the circumstances of the loss and the level of attachment to the person who died. Mourning is the process by which people adapt to a loss. Mourning is greatly influenced by cultural beliefs, practices, and rituals (Casarett, Kutner, & Abrahm,2001).

The Process of Grieving

Typical grief reactions involve emotional, mental, physical, and social responses. These reactions can include feelings of numbness, anger, guilt, anxiety, sadness, and despair. The individual can experience difficulty concentrating, sleep and eating problems, loss of interest in formerly pleasurable activities, physical problems, and even illness. Research has demonstrated that the immune systems of individuals grieving is suppressed and their healthy cells behave more sluggishly, resulting in greater susceptibility to illnesses (Parkes & Prigerson, 2010). However, the intensity and duration of typical grief symptoms do not match those seen in severe grief reactions, and symptoms typically diminish within 6-10 weeks (Youdin, 2016).

Prolonged and Complicated Grief. After the loss of a loved one, however, some individuals experience complicated grief, which includes atypical grief reactions (Newson, Boelen, Hek, Hofman, & Tiemeier, 2011). Symptoms of complicated grief include: Feelings of disbelief, a preoccupation with the dead loved one, distressful memories, feeling unable to move on with one’s life, and a yearning for the deceased. Additionally, these symptoms may last six months or longer and mirror those seen in major depressive disorder (Youdin, 2016).

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association, 2013), distinguishing between major depressive disorder and complicated grief requires clinical judgment. The psychologist needs to evaluate the client’s individual history and determine whether the symptoms are focused entirely on the loss of the loved one and represent the individual’s cultural norms for grieving, which would be appropriate. Those who seek assistance for complicated grief usually have experienced traumatic forms of bereavement, such as unexpected, multiple and violent deaths, or those due to murders or suicides (Parkes & Prigerson, 2010).

Anticipatory Grief. Grief that occurs when a death is expected, and survivors have time to prepare to some extent before the loss is referred to as anticipatory grief. Such anticipation can make adjustment after a loss somewhat easier (Kübler-Ross & Kessler, 2005). Anticipatory grief can include the same denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance experienced in loss one might experience after a death; this can make adjustment after a loss somewhat easier, although a person may then go through the stages of loss again after the death. A death after a long-term, painful illness may bring family members a sense of relief that the suffering is over or the exhausting process of caring for someone who is ill is over. At the same time, when a person has organized all their waking hours around the care of a dying loved one, upon their death the caregiver may experience feelings of emptiness and disorientation in addition to relief.

Survivor’s guilt (also called survivor’s syndrome) is a mental condition that occurs when a person blames themselves for surviving a traumatic event when others did not. It may be found among survivors of combat, natural disasters, epidemics, among the friends and family of those who have died by suicide, and in non-mortal situations such as among those whose colleagues are laid off.

Disenfranchised Grief. Social support from others plays an important role in processes of grieving. However, grief that is not socially recognized is referred to as disenfranchised grief (Doka, 1989). Examples of disenfranchised grief include death due to AIDS, the suicide of a loved one, perinatal deaths, abortions, the death of a pet, lover, or ex-spouse, and psychological losses, such as divorce or a partner developing Alzheimer’s disease. Due to the type of loss, there is no formal mourning practices or recognition by others that would comfort the grieving individual. Consequently, individuals experiencing disenfranchised grief may suffer intensified symptoms due to the lack of social support (Parkes & Prigerson, 2010).

Patterns of grief. It has been said that intense grief lasts about two years or less, but grief is felt throughout life. One loss triggers the feelings that surround another. People grieve with varied intensity throughout the remainder of their lives. It does not end. But it eventually becomes something that a person has learned to live with. As long as we experience loss, we experience grief. Over time, grief becomes interlaced with gratitude for the presence of the loved one in our lives and the cherished memories that remain.

There are layers of grief. Initial denial, marked by shock and disbelief in the weeks following a loss may become an expectation that the loved one will walk in the door. And anger directed toward those who could not save our loved one’s life, may become resentment and bitterness that life did not turn out as we expected. There is no right way to grieve. A bereavement counselor expressed it well by saying that grief touches all of us on the shoulder from time to time throughout life.

Grief and mixed emotions go hand in hand. A sense of relief is accompanied by regrets, and periods of reminiscing about our loved ones are interspersed with feeling haunted by them in death. Our outward expressions of loss are also sometimes contradictory. We want to move on but at the same time are saddened by going through a loved one’s possessions and giving them away. We may no longer feel sexual arousal or we may want sex to feel connected and alive. We need others to befriend us but may get angry at their attempts to console us. These contradictions are normal and we need to allow ourselves and others to grieve in their own time and in their own ways.

The “death-denying, grief-dismissing world” is often the approach to grief in our modern society. We are asked to grieve privately, quickly, and to medicate our suffering. Employers grant us 3 to 5 days for bereavement, if our loss is that of an immediate family member. And such leaves are sometimes limited to no more than one per year. Yet grief takes much longer and the bereaved are seldom ready to perform well on the job. It becomes a clash between life having to continue, and the individual being unready for it to do so. One coping mechanism that can help smooth out this conflict is called the fading affect bias. Based on a collection of similar findings, the fading affect bias suggests that negative events, such as the death of a loved one, tend to lose their emotional intensity at a faster rate than pleasant events (Walker et al., 2003). This is believed to help enhance pleasant experiences and avoid the negative emotions associated with unpleasant ones, thus helping the individual return to his or her normal daily routines following a loss.

Factors that Affect Grief and Bereavement

Grief reactions vary depending on whether a loss was anticipated or unexpected (e.g., parents do not expect to lose their children), and whether or not it occurred suddenly or after a long illness, and whether or not the survivor feels responsible for the death. Struggling with the question of responsibility is particularly felt by those who lose a loved one to suicide or overdose (Gibbons et al., 2018). These survivors may torment themselves with endless “what ifs,” even if they know cognitively that there was nothing more that could have been done.

And family members may also hold one another responsible for the loss. The same may be true for any sudden or unexpected death, making conflict an added complication to the grieving process. Much of this laying of blame is an effort to think that we have some control over these losses; the assumption being that if we do not repeat the same mistakes, we can control what happens in our life and prevent such losses in the future. While grief describes the response to loss, bereavement describes the state of being following the death of someone.

As we’ve already learned in terms of attitudes toward death, individuals’ own lifespan developmental stage and cognitive level can influence their emotional and behavioral reactions to the death of someone they know. But what about the impact of the type of death or age of the deceased or relationship to the deceased upon bereavement?

Death of a Child

Death of a child can take the form of a loss in infancy such as miscarriage or stillbirth or neonatal death, SIDS. Alternatively, death can take an older child, adolescent, or adult child. In most cases, parents find the grief almost unbearably devastating, and the death of a child tends to hold greater risk for negative psychical and psychological outcomes than any other loss. This loss also begins a lifelong process: One does not “get over” the death but instead must bear, assimilate, and live with it. Intervention and comforting support can make a big difference to the survival of a parent in this type of grief but, the risk for negative outcomes is great and may include family breakup, depression, or suicide. Feelings of guilt, whether legitimate or not, are pervasive, and the dependent nature of the relationship predisposes parents to feelings of responsibility, and hence to a variety of problems as they seek to cope with this great loss. Parents who suffer miscarriage or a regretful or coerced abortion may experience resentment towards others who experience successful pregnancies. And seeing other children who are the age that the child would have been had they lived can be painful and triggering.

Suicide and Drug Overdoses

Suicide rates are growing worldwide and over the last thirty years there has been international research to gather knowledge about who is “at-risk” and to find out how to successfully intervene to curb this phenomenon. When a parent loses their child through suicide (and suicide is the second leading cause of death during adolescence), it is traumatic, sudden, and impacts all those who loved this child. Suicide leaves many unanswered questions and leaves most parents feeling hurt, angry, and deeply saddened by such a loss. Parents may feel they can’t openly discuss their grief and feel their emotions because of how their child died and how the people around them may perceive the situation. Parents, family members and service providers have all confirmed the unique nature of suicide-related bereavement following the loss of a child. They report that “a wall of silence” goes up around them that shapes how people interact with them. One of the best ways to grieve and move on from this type of loss is to find a support group of other parents who have suffered a similar loss, and to find ways to keep that child as an active part of their lives. It might be privately at first but as parents move away from the silence they can move into a more proactive healing time.

When adolescents or other family members die from a drug overdose, the grieving process can also be prolonged and complicated, with patterns similar to grieving someone who committed suicide. Survivors may experience feelings of guilt, anger, resentment, and helplessness; and may not receive the sympathy and social support from others that they otherwise would. Survivors may worry about the person’s reputation and the value placed on them by society because they committed suicide or died from an accidental overdose, and so may feel defensive, inhibited, or worried about sharing their experience of loss.

Death of a Spouse

The death of a spouse is usually a particularly powerful loss. A spouse often becomes part of the other in unique ways. Many widows and widowers describe losing “half of themselves” and losing their past selves as well. The days, months, and years after the loss of a spouse can echo with emptiness, and learning to live without them may be harder than the survivor expects. The grief experience is unique to each person. Sharing and building a life with another human being, then learning to live alone, can be an adjustment that is more complex than those providing support may realize. Depression and loneliness are very common. Feeling bitter and resentful are also normal feelings for the spouse who is “left behind.” Oftentimes, the widow/widower may feel it necessary to seek professional help in dealing with their new life.

After a long marriage, at older ages, the elderly may find it a very difficult transition to begin anew; but at younger ages as well, the death of a spouse is unexpected and off-time. A marriage relationship is often a profound anchor around which one’s life is organized, and the loss can completely disrupt the life of the survivor. Furthermore, most couples have a division of ‘tasks’ or ‘labor’, (e.g., the husband mows the yard, the wife pays the bills, etc.) which, in addition to dealing with great grief and life changes, means added responsibilities for the bereaved. Immediately after the death of a spouse, there are tasks that must be completed. Planning and financing a funeral can be very difficult if pre-planning was not completed. Changes in insurance, bank accounts, claiming of life insurance, securing childcare are just some of the issues that can be intimidating to someone who is grieving. If there are children still at home, the survivor must take care of them, support them in their grieving processes, and still find time to take care of themselves as well. Social isolation may also become an issue, as many groups composed of couples find it difficult to adjust to the new identity of the bereaved, and the bereaved themselves have great challenges in reconnecting with others. In fact, seeing other couples still together may be intensely painful. Widows in many cultures, for instance, wear black for the rest of their lives to signify the loss of their spouse and their ongoing grief. Only in more recent decades has this tradition been reduced to shorter periods of time.

Death of a Parent

When an adult child loses a parent in later adulthood, it is considered to be “timely” and so a normative life course event. This allows the adult children to feel a permitted level of grief. However, research shows that the death of a parent in an adult’s midlife is not experienced as a simple “normative life event” by any measure, but instead represents a major life transition that can trigger an evaluation of one’s own life or mortality. Others may shut out friends and family in processing the loss of someone with whom they have had the longest relationship (Marshall, 2004). And the grieving process can be especially challenging if the parent-child relationship was contentious or difficult, and many issues were unresolved.

Death of a Sibling

The loss of a sibling can be a devastating life event. Despite this, sibling grief is often the most disenfranchised or overlooked of the four main forms of grief, especially with regard to adult siblings. Grieving siblings are often referred to as the ‘forgotten mourners’ who are made to feel as if their grief is not as severe as their parents’ grief. However, the sibling relationship tends to be the longest significant relationship since it can last for the lifespan, and siblings who have been part of each other’s lives since birth, such as twins, help form and sustain each other’s identities. With the death of one sibling comes the loss of that part of the survivor’s identity because “your identity is based on having them there.”

The sibling relationship is a unique one, as they share a special bond and a common history from birth, have a certain role and place in the family, often complement each other, and share genetic traits. Siblings who enjoy a close relationship participate in each other’s daily lives and special events, confide in each other, share joys, spend leisure time together (whether they are children or adults), and have a relationship that not only exists in the present but often looks toward a future together (even into retirement). Surviving siblings lose this “companionship and a future” with their deceased siblings (White, 2006).

Conclusion

Death and dying, like every other developmental task across the lifespan, are biological, psychological, and social processes. All lifespan perspectives begin at conception and end at death, so textbooks cover from the cradle to the grave, or from “sperm to worm” or from “womb to tomb.” Many philosophers and spiritual guides suggest that you should “Let death be your advisor.” This phase has many meanings, but as Carlos Castaneda explains, “Death is the only wise advisor that we have. Whenever you feel, as you always do, that everything is going wrong and you’re about to be annihilated, turn to your death and ask if that is so. Your death will tell you that you’re wrong; that nothing really matters outside its touch. Your death will tell you, ‘I haven’t touched you yet.” Death helps us keep life in perspective, reminds us what is really important, encourages us to treasure and make good use of the time we have remaining, and ties us to all of living things, past, present, and future.