Beginnings: Conception and Prenatal Development

Behavioral Genetics

Behavioral Genetics is the scientific study of the interplay between genetic and environmental contributions to behavior. Often referred to as the nature/nurture debate, Gottlieb (1998, 2000, 2002) suggests an analytic framework for this debate that recognizes the interplay between the environment, behavior, and genetic expression. This bidirectional interplay indicates that the environment can affect the expression of genes just as genetic predispositions can impact a person’s potentials. Additionally, environmental circumstances can trigger symptoms of a genetic disorder. For example, a person who has sickle cell anemia, a recessive gene linked disorder, can experience a sickle cell crisis under conditions of oxygen deprivation. Or, someone predisposed genetically to type-two diabetes can trigger the disease through poor diet and little exercise.

Research has shown how the environment and genotype interact in several ways. Genotype-Environment Correlations refer to the processes by which genetic factors contribute to variations in the environment (Plomin, DeFries, Knopik, & Niederhiser, 2013). There are three types of genotype-environment correlations:

Passive genotype-environment correlations occur when children passively inherit both the genes and the environments their family provides. Certain behavioral characteristics, such as being athletically inclined, may run in families. Children in these families have inherited both the genes that would enable success at these activities, and an environment that encourages them to engage in sports. Figure 3.1 highlights this correlation by demonstrating how a family passes on water skiing skills through both genetics and environmental opportunities.

Evocative genotype-environment correlations refer to how the social environment reacts to individuals based on their inherited characteristics. For example, whether children have a more outgoing or shy temperament will affect how they are treated by others.

Active genotype-environment correlations occur when individuals seek out environments that support their genetic tendencies. This is also referred to as niche picking. For example, children who are musically inclined seek out music instruction and opportunities that then facilitate their natural musical ability.

Conversely, genotype-environment interactions involve genetic susceptibility to the environment. Adoption studies provide evidence for genotype-environment interactions. For example, the Early Growth and Development Study (Leve, Neiderhiser, Scaramella, & Reiss, 2010) followed 360 adopted children and their adopted and biological parents in a longitudinal study. Results have shown that children whose biological parents exhibited psychopathology, exhibited significantly fewer behavior problems when their adoptive parents used more structured (vs. unstructured) parenting. Additionally, higher levels of psychopathology in adoptive parents increased the risk that children would develop behavior problems, but only when the biological parents’ psychopathology was also high. Consequently, these results show that environmental effects on behavior differ based on the individual's genotype, especially the effects of stressful environments on genetically at-risk children.

Lastly, the study of epigenetics examines modifications in DNA that affect gene expression and are passed on when the cells divide. Environmental factors, such as nutrition, stress, and teratogens are thought to change gene expression by switching genes on and off. These gene changes can then be inherited by daughter cells. This would explain why monozygotic or identical twins may increasingly differ in gene expression with age. For example, Fraga et al. (2005) found that when examining differences in DNA, a group of monozygotic twins were indistinguishable during the early years. However, when the twins were older there were significant discrepancies in their gene expression, most likely due to different experiences. These differences included a range of personal characteristics, including susceptibilities to disease.

Box 3.1 The Human Genome Project

In 1990 the Human Genome Project (HGP), an international scientific endeavor, began the task of sequencing the 3 billion base pairs that make up the human genome. In April of 2003, more than two years ahead of schedule, scientists gave us the genetic blueprint for building a human. Since then, using this information from the HGP, researchers have discovered the genes involved in over 1800 diseases. In 2005 the HGP amassed a large data base called HapMap that catalogs genetic variations in 11 global populations. Data on genetic variation can improve our understanding of differential risk for disease and reactions to medical treatments, such as drugs. Pharmacogenomic researchers have already developed tests to determine whether a patient will respond favorably to certain drugs used in the treatment of breast cancer, lung cancer, or HIV by using information from HapMap (NIH, 2015).

Future directions for the HGP include identifying the genetic markers for all 50 major forms of cancer (The Cancer Genome Atlas), continuing to create more effective drugs for the treatment of disease, and examining the legal, social and ethical implications of genetic knowledge (NIH, 2015).

From the outset, the HGP established ethical issues one of their main concerns. Part of the HGP’s budget supports research and holds workshops that address these concerns. Who owns this information, and how the availability of genetic information may influence healthcare and its impact on individuals, their families, and the greater community are just some of the many questions being addressed (NIH, 2015).

Learning Objectives: Prenatal Development

- Describe the changes that occur in the three periods of prenatal development

- Describe what occurs during prenatal brain development

- Define teratogens and describe the factors that influence their effects

- List and describe the effects of several common teratogens

- Explain maternal and paternal factors that affect the developing fetus

- Explain the types of prenatal assessment

- Describe both the minor and major complications of pregnancy

- Describe two common procedures to assess the condition of the newborn

- Describe problems newborns experience before, during, and after birth

Prenatal Development

Now we turn our attention to prenatal development which is divided into three periods: (1) the germinal period, (2) the embryonic period, and (3) the fetal period. The following is an overview of some of the changes that take place during each period.

The Germinal Period

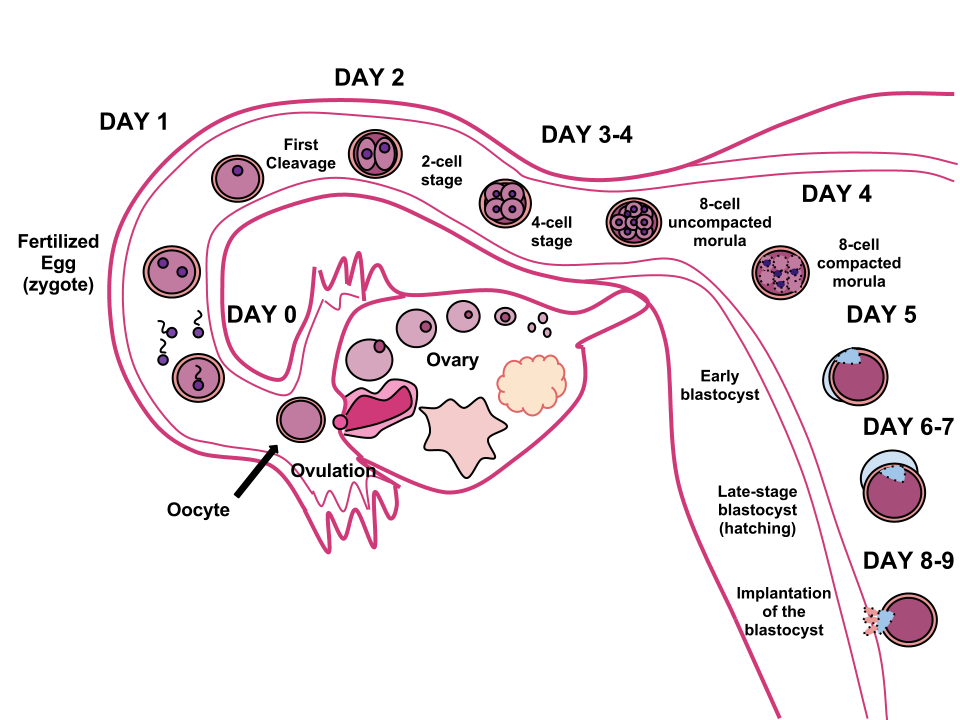

The germinal period (about 14 days in length) lasts from conception to implantation of the fertilized egg in the lining of the uterus (see Figure 3.2). At ejaculation millions of sperm are released into the vagina, but only a few reach the egg and typically only one fertilizes the egg. Once a single sperm has entered the wall of the egg, the wall becomes hard and prevents other sperm from entering. After the sperm has entered the egg, the tail of the sperm breaks off and the head of the sperm, containing the genetic information from the father, unites with the nucleus of the egg. The egg is typically fertilized in the top section of the fallopian tube and continues its journey to the uterus. As a result, a new cell is formed. This cell, containing the combined genetic information from both parents, is referred to as a zygote.

During this time, the organism begins cell division through mitosis. After five days of mitosis there is a group of 100 cells, which is now called a blastocyst. The blastocyst consists of both an inner and outer group of cells. The inner group of cells, or embryonic disk will become the embryo, while the outer group of cells, or trophoblast, becomes the support system which nourishes the developing organism. This stage ends when the blastocyst fully implants into the uterine wall (U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2015a). Approximately 50-75% of blastocysts do not implant in the uterine wall (Betts et al., 2019).

Mitosis is a fragile process and fewer than half of all zygotes survive beyond the first two weeks (Hall, 2004). Some of the reasons for this include the egg and sperm do not join properly, meaning that their genetic material does not combine; there is too little or damaged genetic material; the zygote does not replicate; or the blastocyst does not implant into the uterine wall. The failure rate is higher for in vitro conceptions. Figure 3.3 illustrates the journey of the ova from its release to its fertilization, cell duplication, and implantation into the uterine lining.

The Embryonic Period

Starting the third week the blastocyst has implanted in the uterine wall. Upon implantation this multi-cellular organism is called an embryo. Now blood vessels grow, forming the placenta. The placenta is a structure connected to the uterus that provides nourishment and oxygen from the mother to the developing embryo via the umbilical cord. During this period, cells continue to differentiate. Growth during prenatal development occurs in two major directions: from head to tail called cephalocaudal development and from the midline outward referred to as proximodistal development. This means that those structures nearest the head develop before those nearest the feet and those structures nearest the torso develop before those away from the center of the body (such as hands and fingers). The head develops in the fourth week and the precursor to the heart begins to pulse. In the early stages of the embryonic period, gills and a tail are apparent. However, by the end of this stage they disappear and the organism takes on a more human appearance. Some organisms fail during the embryonic period, usually due to gross chromosomal abnormalities. As in the case of the germinal period, often the gestational parent does not yet know that they are pregnant.

It is during this stage that the major structures of the body are taking form making the embryonic period the time when the organism is most vulnerable to the greatest amount of damage if exposed to harmful substances. Potential mothers are not often aware of the risks they introduce to the developing embryo during this time. The embryo is approximately 1 inch in length and weighs about 8 grams at the end of eight weeks (Betts et al., 2019). The embryo can move and respond to touch at this time.

The Fetal Period

From the ninth week until birth, the organism is referred to as a fetus. During this stage, the major structures are continuing to develop. By the third month, the fetus has all its body parts including external genitalia. In the following weeks, the fetus will develop hair, nails, teeth and the excretory and digestive systems will continue to develop. The fetus is about 3 inches long and weighs about 28 grams.

During the 4th - 6th months, the eyes become more sensitive to light and hearing develops. The respiratory system continues to develop, and reflexes such as sucking, swallowing and hiccupping, develop during the 5th month. Cycles of sleep and wakefulness are present at this time as well. The first chance of survival outside the womb, known as the age of viability is reached at about 24 weeks (Morgan, Goldenberg, & Schulkin, 2008). The majority of the neurons in the brain have developed by 24 weeks, although they are still rudimentary, and the glial or nurse cells that support neurons continue to grow. At 24 weeks the fetus can feel pain (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 1997).

Between the 7th - 9th months, the fetus is primarily preparing for birth. It is exercising its muscles and its lungs begin to expand and contract. The fetus gains about 5 pounds and 7 inches during this last trimester of pregnancy, and during the 8th month a layer of fat develops under the skin. This layer of fat serves as insulation and helps the baby regulate body temperature after birth.

At around 36 weeks the fetus is almost ready for birth. It weighs about 6 pounds and is about 18.5 inches long. By week 37 all of the fetus’s organ systems are developed enough that it could survive outside the mother’s uterus without many of the risks associated with premature birth. The fetus continues to gain weight and grow in length until approximately 40 weeks. By then the fetus has very little room to move around and birth becomes imminent. The progression through the stages is shown in Figure 3.5.

Prenatal Brain Development

Prenatal brain development begins in the third gestational week with the differentiation of stem cells, which are capable of producing all the different cells that make up the brain (Stiles & Jernigan, 2010). The location of these stem cells in the embryo is referred to as the neural plate. By the end of the third week, two ridges appear along the neural plate first forming the neural groove and then the neural tube. The open region in the center of the neural tube forms the brain’s ventricles and spinal canal. By the end of the embryonic period, or week eight, the neural tube has further differentiated into the forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain.

Brain development during the fetal period involves neuron production, migration, and differentiation. From the early fetal period until midgestation, most of the 85 billion neurons have been generated and many have already migrated to their brain positions. Neurogenesis, or the formation of neurons, is largely completed after five months of gestation. One exception is in the hippocampus, which continues to develop neurons throughout life. Neurons that form the neocortex, or the layer of cells that lie on the surface of the brain, migrate to their location in an orderly way. Neural migration is mostly completed in the cerebral cortex by 24 weeks (Poduri & Volpe, 2018).

Once in position, neurons begin to produce dendrites and axons that begin to form the neural networks responsible for information processing. Regions of the brain that contain the cell bodies are referred to as the gray matter because they look gray in appearance. The axons that form the neural pathways make up the white matter because they are covered in myelin, a fatty substance that is white in appearance. Myelin aids in both the insulation and efficiency of neural transmission. Although cell differentiation is complete at birth, the growth of dendrites, axons, and synapses continue for years.

Teratogens

Good prenatal care is essential for healthy development. The developing child is most at risk for severe problems during the first three months of development. Unfortunately, this is a time when many gestational parents are unaware that they are pregnant. Today, we know many of the factors that can jeopardize the health of the developing child. The study of factors that contribute to birth defects is called teratology. Teratogens are environmental factors that can contribute to birth defects, and include some parental diseases, pollutants, drugs and alcohol.

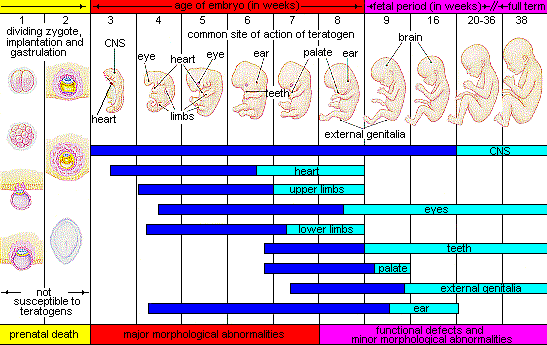

Factors influencing prenatal risks. There are several considerations in determining the kind and amount of damage that can result from exposure to a particular teratogen (Berger, 2005). These include:

- The timing of the exposure. Structures in the body are vulnerable to the most severe damage when they are forming. If a substance is introduced during a particular structure's critical period (time of development), the damage to that structure may be greater. For example, the ears and arms reach their critical periods at about 6 weeks after conception. If a mother exposes the embryo to certain substances during this period, its ears and arms may be malformed.

- The amount of exposure. Some substances are not harmful unless the amounts reach a certain level. The critical level depends in part on the size and metabolism of the mother.

- The number of teratogens. Fetuses exposed to multiple teratogens typically have more problems than those exposed to only one.

- Genetics. Genetic make-up also plays a role in the impact a particular teratogen has on a child. This is suggested by research showing that fraternal twins exposed to the same prenatal environment, do not always experience the same teratogenic effects. The genetic make-up of the mother can also have an effect; some gestational parents may be more resistant to teratogenic effects than others.

- Being male or female. Males are more likely to experience damage due to teratogens than are females. It is believed that the Y chromosome, which contains fewer genes than the X, may make males more vulnerable.

Figure 3.6 illustrates the timing of teratogen exposure and the types of structural defects that can occur during the prenatal period.

Alcohol. One of the most common teratogens is alcohol, and because half of all pregnancies in the United States are unplanned, it is recommended that people of child-bearing age take great caution against drinking alcohol when not using birth control or when pregnant (CDC, 2005). Alcohol use during pregnancy is the leading preventable cause of intellectual disabilities in children in the United States (Maier & West, 2001). Alcohol consumption at any point during pregnancy, but particularly during the second month of prenatal development, may lead to neurocognitive and behavioral difficulties that can last a lifetime.

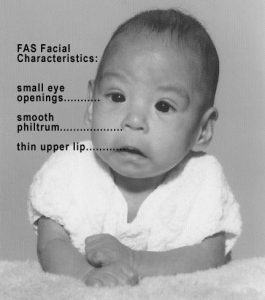

In extreme cases, alcohol consumption during pregnancy can lead to fetal death, but also can result in Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD), which is an umbrella term for the range of effects that can occur due to alcohol consumption during pregnancy (March of Dimes, 2016a). The most severe form of FASD is Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS). Children with FAS share certain physical features such as flattened noses, small eye holes, and small heads (see Figure 3.7). Cognitively, these children have poor judgment, poor impulse control, higher rates of ADHD, learning issues, and lower IQ scores. These developmental problems and delays persist into adulthood (Streissguth, Barr, Kogan, & Bookstein, 1996) and contribute to criminal behavior, psychiatric problems, and unemployment (CDC, 2016a). Based on animal studies, it has been hypothesized that a gestational parent's alcohol consumption during pregnancy may predispose their child to like alcohol (Youngentob, Molina, Spear, & Youngentob, 2007). Binge drinking, or 4 or more drinks in 2 to 3 hours, during pregnancy increases the chance of having a baby with FASD (March of Dimes, 2016a).

Tobacco. Another widely used teratogen is tobacco; in fact, in 2016, more than 7% of pregnant women smoked in 2016 (Someji & Beltrán-Sánchez, 2019). According to Tong et al. (2013) in conjunction with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, data from 27 sites in 2010 representing 52% of live births, showed that among women with recent live births:

- About 23% reported smoking in the 3 months prior to pregnancy.

- Almost 11% reported smoking during pregnancy.

- More than half (54.3%) reported that they quit smoking by the last 3 months of pregnancy.

- Almost 16% reported smoking after delivery.

When comparing the ages of women who smoked:

- Women <20, 13.6% smoked during pregnancy

- Women 20–24 ,17.6% smoked during pregnancy

- Women 25–34 , 8.8% smoked during pregnancy

- Women ≥35, 5.7% smoked during pregnancy

The findings among racial and ethnic groups indicated that smoking during pregnancy was highest among American Indians/Alaska Natives (26.0%) and lowest among Asians/Pacific Islanders (2.1%).

When a pregnant person smokes, the fetus is exposed to dangerous chemicals including nicotine, carbon monoxide, and tar, which lessen the amount of oxygen available to the fetus. Oxygen is important for overall growth and development. Tobacco use during pregnancy has been associated with ecotopic pregnancy (fertilized egg implants itself outside of the uterus), placenta previa (placenta lies low in the uterus and covers all or part of the cervix), placenta abruption (placenta separates prematurely from the uterine wall), preterm delivery, low birth weight, stillbirth, fetal growth restriction, sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), birth defects, learning disabilities, and early puberty in girls (Center for Disease Control, 2015d).

When gestational parents are exposed to secondhand smoke during pregnancy, this also increases the risk of low-birth weight infants. In addition, exposure to thirdhand smoke, or toxins from tobacco smoke that linger on clothing, furniture, and in locations where smoking has occurred, can have a negative impact on infants’ lung development. Rehan, Sakurai, and Torday (2011) found that prenatal exposure to thirdhand smoke played a greater role in altered lung functioning than postnatal exposure.

Prescription/Over-the-counter Drugs: About 70% of pregnant people take at least one prescription drug (March of Dimes, 2016e). A person should not be taking any prescription medication during pregnancy unless it was prescribed by a health care provider who knows that person is pregnant. Some prescription drugs can cause birth defects, problems in overall health, and development of the fetus. Over-the-counter drugs are also a concern during the prenatal period because they may cause certain health problems. For example, the pain reliever ibuprofen can cause serious blood flow problems to the fetus during the last three months.

Illicit Drugs: Common illicit drugs include marijuana, cocaine, ecstasy and other club drugs, heroin, and prescription drugs that are abused. It is difficult to fully determine the effects of particular illicit drugs on a developing fetus because most mothers who use, use more than one substance and have other unhealthy behaviors. These include smoking, drinking alcohol, not eating healthy meals, and being more likely to get a sexually transmitted disease.

However, several problems seem clear. The use of cocaine is connected with low birth weight, stillbirths, and spontaneous abortion. Heavy marijuana use is associated with problems in brain development (March of Dimes, 2016c). If a baby’s gestational parent used an addictive drug during pregnancy that baby can get addicted to the drug before birth and go through drug withdrawal after birth, also known as Neonatal abstinence syndrome (March of Dimes, 2015d). Other complications of illicit drug use include premature birth, smaller than normal head size, birth defects, heart defects, and infections. Additionally, babies born to gestational parents who use drugs may have problems later in life, including death from sudden infant death syndrome, slower than normal growth, and learning and behavior difficulties. Children of substance abusing parents are also considered at high risk for a range of biological, developmental, academic, and behavioral problems, including developing substance abuse problems of their own (Conners, et al., 2003).

Box 3.2 Should People Who Use Drugs During Pregnancy Be Arrested and Jailed?

People who use drugs or alcohol during pregnancy can cause serious lifelong harm to their children. Some people have advocated mandatory screenings for people who become pregnant and have a history of drug abuse, and if the people continue using, to arrest, prosecute, and incarcerate them (Figdor & Kaeser, 1998). This policy was tried in Charleston, South Carolina 20 years ago. The policy was called the Interagency Policy on Management of Substance Abuse During Pregnancy and had disastrous results.

The Interagency Policy applied to patients attending the obstetrics clinic at MUSC, which primarily serves patients who are indigent or on Medicaid. It did not apply to private obstetrical patients. The policy required patient education about the harmful effects of substance abuse during pregnancy. A statement also warned patients that protection of unborn and newborn children from the harms of illegal drug abuse could involve the Charleston police, the Solicitor of the Ninth Judicial Court, and the Protective Services Division of the Department of Social Services (DSS). (Jos, Marshall, & Perlmutter, 1995, pp. 120–121).

Rather than helping newborns, this policy seemed to deter gestational parents from seeking prenatal care and to deter them from seeking other social services. And because this policy was applied solely to low-income people, it also resulted in lawsuits. The program was canceled after 5 years, during which time 42 gestational parents were arrested. A federal agency later determined that the program involved human experimentation without the approval and oversight of an institutional review board (IRB).

In July 2014, Tennessee enacted a law that allows people who illegally use a narcotic drug while pregnant to be prosecuted for assault if her infant is harmed or addicted to the drug (National Public Radio, 2015). According to the National Public Radio report, a baby is born dependent on a drug every 30 minutes in Tennessee, which is a rate three times higher than the national average. However, since the law took effect the number of babies born having drug withdrawal symptoms has not diminished. Critics contend that the criminal justice system should not be involved in what is considered a healthcare problem. What do you think? Do you consider the issue of gestational parents using illicit drugs more of a legal or a medical concern?

Pollutants. There are more than 83,000 chemicals used in the United States with little information on their effects on unborn children (March of Dimes, 2016b).

- Lead poisoning. An environmental pollutant of significant concern is lead, which has been linked to fertility problems, high blood pressure, low birth weight, prematurity, miscarriage, and delayed neurological development. Grossman and Slutsky (2017) found that babies born in Flint Michigan, an area identified with high lead levels in the drinking water, were premature, weighed less than average, and gained less weight than normal.

- Pesticides. Chemicals in certain pesticides are also potentially damaging and may lead to miscarriage, low birth weight, premature birth, birth defects, and learning problems, (March of Dimes, 2014).

- Bisphenol A. Prenatal exposure to bisphenol A (BPA), a chemical commonly used in plastics and food and beverage containers, may disrupt the action of certain genes contributing to particular birth defects (March of Dimes, 2016b).

- Radiation. If a gestational parent is exposed to radiation, it can get into the bloodstream and pass through the umbilical cord to the fetus. Radiation can also build up in body areas close to the uterus, such as the bladder. Exposure to radiation can cause result in miscarriage, affect brain development, slow the baby’s growth, or cause birth defects or cancer.

- Mercury. Mecury, a heavy metal, can cause brain damage and affect the baby’s hearing and vision. This is why people are cautioned about the amount and type of fish they consume during pregnancy.

Toxoplasmosis. The tiny parasite, toxoplasma gondii, causes an infection called toxoplasmosis. According to the March of Dimes (2012d), toxoplasma gondii infects more than 60 million people in the United States. A healthy immune system can keep the parasite at bay resulting in no symptoms, so most people do not know they are infected. As a routine prenatal screening frequently does not test for the presence of this parasite, pregnant people may want to talk to their health-care provider about being tested. Toxoplasmosis can cause premature birth, stillbirth, and can result in birth defects to the eyes and brain. While most babies born with this infection show no symptoms, ten percent may experience eye infections, enlarged liver and spleen, jaundice, and pneumonia. To avoid being infected, gestational parents should avoid eating undercooked or raw meat and unwashed fruits and vegetables, touching cooking utensils that touched raw meat or unwashed fruits and vegetables, and touching cat feces, soil, or sand. If people think they may have been infected during pregnancy, they should have their newborn tested.

Sexually transmitted diseases. Gonorrhea, syphilis, and chlamydia are sexually transmitted infections that can be passed to the fetus by an infected gestational parent. Gestational parents should be tested as early as possible to minimize the risk of spreading these infections to their unborn children. Additionally, the earlier the treatment begins, the better the health outcomes for parent and baby (CDC, 2016d). Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) can cause an ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage, premature rupture of the amniotic sac, premature birth, still births. and birth defects (March of Dimes, 2013). Although some STDs can cross the placenta and infect the developing fetus, most babies become infected with STDS while passing through the birth canal during delivery.

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). One of the most potentially devastating teratogens is HIV. HIV and Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) are leading causes of illness and death in the United States (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2015). One of the main ways children under age 13 become infected with HIV is via mother-to-child transmission of the virus prenatally, during labor, or by breastfeeding (CDC, 2016c). There are measures that can be taken to lower the chance the child will contract the disease. HIV positive gestational parents who take antiviral medications during their pregnancy greatly reduce the chance of passing the virus to the fetus. The risk of transmission is less than 2%; in contrast, if the gestational parent does not take antiretroviral drugs, the risk is elevated to 25% (CDC, 2016b). However, the long-term risks of prenatal exposure to the medication are not known. It is recommended that people with HIV deliver the child by c-section, and that after birth they avoid breast feeding.

German measles (or rubella). Rubella, also called German measles, is an infection that causes mild flu-like symptoms and a rash on the skin. Rubella in the gestational parent has been associated with a number of birth defects. If the gestational parent contracts the disease during the first three months of pregnancy, damage can occur in the eyes, ears, heart or brain of the unborn child. if the pregnant person has German measles before the 11th week of prenatal development, deafness is almost certain and brain damage can also result. People in the United States are much less likely to be afflicted with rubella, because most receive childhood vaccinations which protect them from the disease.

Maternal Factors

Gestational parent over 35. Most people over 35 who become pregnant are in good health and have healthy pregnancies. However, according to the March of Dimes (2016d), people over age 35 have an increased risk of:

- Fertility problems

- High blood pressure

- Diabetes

- Miscarriages

- Placenta Previa

- Cesarean section

- Premature birth

- Stillbirth

- A baby with a genetic disorder or other birth defects

Because a gestational parent is born with all their eggs, environmental teratogens can affect the quality of the eggs as they get older. Also, their reproductive system ages which can adversely affect the pregnancy. Some people over 35 choose special prenatal screening tests, such as a maternal blood screening, to determine if there are any health risks for the baby.

Although there are medical concerns associated with having a child later in life, there are also many positive consequences to being a more mature parent. Older parents are more confident, less stressed, and typically married, which can provide family stability. Their children perform better on math and reading tests, and they are less prone to injuries or emotional troubles (Albert, 2013). People who choose to wait are often well educated and lead healthy lives. According to Gregory (2007), older women are more stable, demonstrate a stronger family focus, possess greater self-confidence, and have more money. Having a child later in one’s career equals overall higher wages. In fact, for every year a gestational parent delays becoming a parent, they make 9% more in lifetime earnings. Lastly, gestational parents who delay having children actually live longer. Sun et al. (2015) found that women who had their last child after the age of 33 doubled their chances of living to age 95 or older than women who had their last child before their 30th birthday. A gestational parent's natural ability to have a child at a later age indicates that their reproductive system is aging slowly, and consequently so is the rest of their body.

Teenage pregnancy. A teenage gestational parent is at a greater risk for complications during pregnancy, including anemia and high blood pressure. These risks are even greater for those under age 15. Infants born to teenage gestational parents have a higher risk of being born prematurely and having low birthweight or other serious health problems. Premature and low birthweight babies may have organs that are not fully developed which can result in breathing problems, bleeding in the brain, vision loss, and serious intestinal problems. Very low birthweight babies (less than 3 1/3 pounds) are more than 100 times as likely to die, and moderately low birthweight babies (between 3 1/3 and 5 ½ pounds) are more than 5 times as likely to die in their first year, than normal weight babies (March of Dimes, 2012c). Again, the risk is highest for babies of gestational parents under age 15. A primary reason for these health issues is that teenagers are the least likely of all age groups to get early and regular prenatal care. Additionally, they may engage in risky behaviors during pregnancy, including eating unhealthy food, smoking, drinking alcohol, and taking drugs. Additional concerns for teenagers are repeat births. About 25% of teen gestational parents under age 18 have a second baby within 2 years after the first baby’s birth.

Gestational diabetes. Seven percent of pregnant people develop gestational diabetes (March of Dimes, 2015b). Diabetes is a condition where the body has too much glucose in the bloodstream. Most pregnant people have their glucose level tested at 24 to 28 weeks of pregnancy. Gestational diabetes usually goes away after the gestational parent gives birth, but it might indicate a risk for developing diabetes later in life. If untreated, gestational diabetes can cause premature birth, stillbirth, infant breathing problems at birth, jaundice, or low blood sugar. Babies born to mothers with gestational diabetes can also be considerably heavier (more than 9 pounds) making the labor and birth process more difficult. For expectant mothers, untreated gestational diabetes can cause preeclampsia (high blood pressure and signs that the liver and kidneys may not be working properly) discussed later in the chapter. Risk factors for gestational diabetes include age (being over age 25), being overweight or gaining too much weight during pregnancy, a family history of diabetes, having had gestational diabetes with a prior pregnancy, and race and ethnicity (mothers who are African-American, Native American, Hispanic, Asian, or Pacific Islander have a higher risk). Eating healthy food and maintaining a healthy weight during pregnancy can reduce the chance of gestational diabetes. People who already have diabetes and become pregnant need to attend all their prenatal care visits, and follow the same advice as those for people with gestational diabetes as the risk of preeclampsia, premature birth, birth defects, and stillbirth are the same.

High blood pressure (Hypertension). Hypertension is a condition in which the pressure against the wall of the arteries becomes too high. There are two types of high blood pressure during pregnancy, gestational and chronic. Gestational hypertension only occurs during pregnancy and goes away after birth. Chronic high blood pressure refers to people who already had hypertension before the pregnancy or to those who developed it during pregnancy and it continued after birth. According to the March of Dimes (2015c) about 8 in every 100 pregnant people have high blood pressure. High blood pressure during pregnancy can cause premature birth and low birth weight (under five and a half pounds), placental abruption, and mothers can develop preeclampsia.

Rh disease. Rh is a protein found in the blood. Most people are Rh positive, meaning they have this protein. Some people are Rh negative, meaning this protein is absent. Gestational parents who are Rh negative are at risk of having a baby with a form of anemia called Rh disease (March of Dimes, 2009). A father who is Rh-positive and gestational parent who is Rh-negative can conceive a baby who is Rh-positive. Some of the fetus’s blood cells may get into the mother’s bloodstream and her immune system is unable to recognize the Rh factor. The immune system starts to produce antibodies to fight off what it thinks is a foreign invader. Once the pregnant person's body produces immunity, the antibodies can cross the placenta and start to destroy the red blood cells of the developing fetus. As this process takes time, often the first Rh positive baby is not harmed, but because the pregnant person's body continues to produce antibodies to the Rh factor across their lifetime, subsequent pregnancies can pose greater risk for an Rh positive baby. In newborns, Rh disease can lead to jaundice, anemia, heart failure, brain damage and death.

Weight gain during pregnancy. According to March of Dimes (2016f) during pregnancy most people need only an additional 300 calories per day to aid in the growth of the fetus. Gaining too little or too much weight during pregnancy can be harmful. People who gain too little may have a baby who is low-birth weight, while those who gain too much are likely to have a premature or large baby. There is also a greater risk for the gestational parent developing preeclampsia and diabetes, which can cause further problems during the pregnancy. Table 3.1 shows the healthy weight gain during pregnancy. Putting on the weight slowly is best. Gestational parents who are concerned about their weight gain should talk to their health care provider.

Table 3.1 Weight gain during pregnancy

| If you were a healthy weight before pregnancy | If you were underweight before pregnancy | If you were overweight before pregnancy | If you were obese before pregnancy |

|---|---|---|---|

| • gain 25-35lbs • 1-4½lbs in the first trimester and 1lb per week in the second and third trimesters |

• gain 28-40lbs • 1-4½lbs in the first trimester and a little more than 1lb per week thereafter |

• gain 12-25 lbs • 1-4½lbs in the first trimester and a little more than ½lb per week in the second and third trimesters |

• 11-20lbs • 1-4½lbs in the first trimester and less than ½lb per week in the second and third trimesters |

| Mothers of twins need to gain more in each category |

Stress. It is common to feel stressed during pregnancy, but high levels of stress can cause complications including having a premature or low-birthweight baby. Babies born early or too small are at an increased risk for health problems. Stress-related hormones may cause these complications by affecting a gestational parent's immune systems resulting in an infection and premature birth. Additionally, some people deal with stress by smoking, drinking alcohol, or taking drugs, which can lead to problems in the pregnancy. High levels of stress in pregnancy have also been correlated with problems in the baby’s brain development and immune system functioning, as well as childhood problems such as trouble paying attention and anxiety (March of Dimes, 2012b).

Depression. Depression is a significant medical condition in which feelings of sadness, worthlessness, guilt, and fatigue interfere with one’s daily functioning. Depression can occur before, during, or after pregnancy, and 1 in 7 pregnant people are treated for depression sometime between the year before pregnancy and the year after pregnancy (March of Dimes, 2015a). Women who have experienced depression previously are more likely to have depression while pregnant. Consequences of depression include the baby being born prematurely, having a low birthweight, being more irritable, less active, less attentive, and having fewer facial expressions. About 13% of pregnant people take an antidepressant during pregnancy. It is important that pregnant people taking antidepressants discuss the medication with a health care provider as some medications can cause harm to the developing organism. In fact, birth defects are about 2 to 3 times more likely in people who are prescribed certain Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) for their depression.

Paternal impact. The age of fathers at the time of conception is also an important factor in health risks for children. According to Nippoldt (2015) offspring of men over 40 face an increased risk of miscarriage, autism, birth defects, achondroplasia (bone growth disorder) and schizophrenia. These increased health risks are thought to be due to chromosomal aberrations and mutations that accumulate during the maturation of sperm cells in older men (Bray, Gunnell, & Smith, 2006). However, like older women, the overall risks are small.

In addition, men are more likely than women to work in occupations where hazardous chemicals, many of which have teratogenic effects or may cause genetic mutations, are used (Cordier, 2008). These may include petrochemicals, lead, and pesticides that can cause abnormal sperm and lead to miscarriages or diseases. Men are also more likely to be a source of secondhand smoke for their developing offspring. As noted earlier, smoking by either the mother or around the mother can impede prenatal development.

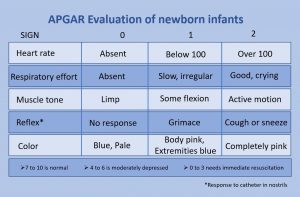

Assessing the Neonate

The Apgar assessment is conducted at one minute and five minutes after birth. This is a very quick way to assess the newborn's overall condition. Five measures are assessed: Heart rate, respiration, muscle tone (assessed by touching the baby's palm), reflex response (the Babinski reflex is tested), and color. A score of 0 to 2 is given on each feature examined. An Apgar of 5 or less is cause for concern. The second Apgar should indicate improvement with a higher score (see Figure 3.11).

Another way to assess the condition of the newborn is the Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale (NBAS). The baby's motor development, muscle tone, and stress response are assessed. This tool has been used around the world to further assess newborn, especially those with low Apgar scores, and to make comparisons of infants in different cultures (Brazelton & Nugent, 1995).

Problems of the Newborn

Anoxia. Anoxia is a temporary lack of oxygen to the brain. Difficulty during delivery may lead to anoxia which can result in brain damage or in severe cases, death. Babies who suffer both low birth weight and anoxia are more likely to suffer learning disabilities later in life as well.

Low birth weight. We have been discussing a number of teratogens associated with low birth weight such as alcohol, tobacco, and so on. A child is considered low birth weight if he or she weighs less than 5 pounds 8 ounces (2500 grams). About 8.2 percent of babies born in the United States are of low birth weight (Center for Disease Control, 2015a). A low birth weight baby has difficulty maintaining adequate body temperature because it lacks the fat that would otherwise provide insulation. Such babies are also at more risk for infection, and 67 percent of these babies are also preterm which can increase their risk for respiratory infection. Very low birth weight babies (2 pounds or less) have an increased risk of developing cerebral palsy.

Additionally, Pettersson, Larsson, D’Onofrio, Almqvist, and Lichtenstein (2019) analyzed fetal growth and found that reduced birth weight was correlated with a small, but significant increase in several psychiatric disorders in adulthood. These include attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Pettersson et al. theorized that “reduced fetal growth compromises brain development during a critical period, which in turn slightly increases the risk not only for neurodevelopmental disorders but also for virtually all mental health conditions” (p. 540). An insufficient supply of oxygen and nutrients for the developing fetus are proposed as factors that increased the risk for neurodevelopmental disorders.

Preterm. A newborn might also have a low birth weight if it is born at less than 37 weeks gestation, which qualifies it as a preterm baby (CDC, 2015c). Early birth can be triggered by anything that disrupts the mother's system. For instance, vaginal infections can lead to premature birth because such infection causes the mother to release anti-inflammatory chemicals which, in turn, can trigger contractions. Smoking and the use of other teratogens can lead to preterm birth. The earlier a woman quits smoking, the lower the chance that the baby will be born preterm (Someji & Beltrán-Sánchez, 2019). A significant consequence of preterm birth includes respiratory distress syndrome, which is characterized by weak and irregular breathing (United States National Library of Medicine, 2015b).

Saybie (name given to her by the hospital), a baby girl born in San Diego, California is now considered the world’s smallest baby ever to survive (Chiu, 2019). She was born in December 2018 at 23 weeks and 3 days weighing only 8.6 ounces (same size as an apple). After five months in the hospital, Saybie went home in May 2019 weighing 5 pounds.

Small-for-date infants. Infants that have birth weights that are below expectation based on their gestational age are referred to as small-for-date. These infants may be full term or preterm, but still weigh less than 90% of all babies of the same gestational age. This is a very serious situation for newborns as their growth was adversely affected. Regev et al. (2003) found that small-for-date infants died at rates more than four times higher than other infants. Remember that many causes of low birth weight and preterm births are preventable with proper prenatal care.

Supplemental Materials

- This documentary follows four babies from different parts of the globe as they navigate their first year of life.

- The following video explains how In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) works as a solution for couples who cannot conceive naturally (e.g., some older couples and some queer couples).

- This U.S. Department of Health and Human Services website shows infant mortality rate statistics by ethnicity.

https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=23

- This Ted Talk features a doula and journalist, Miriam Zoila Pérez, who explores the relationship between race, class. and illness. Further, Pérez discusses a radically compassionate prenatal care program that can buffer pregnant women from the stress that people of color face every day.

- This book provides a troubling study of the role that medical racism plays in the lives of black women who have given birth to premature and low birth weight infants.

Davis, D. (2019). Reproductive Injustice (Vol. 7). New York: NYU Press.

- This article details the experience of Dr. Tressie McMillan Cottom, a professor who dealt with pregnancy and birthing complications due to systemic racism.

- This website provides resources related to Black women and prenatal and maternal health.

https://everymothercounts.org/anti-racist-reading/

- The Center for Disease Control (CDC) has started a program called "Hear Her" to create awareness and provide better medical support for women of color.

https://www.cdc.gov/hearher/index.html

References

Albert, E. (2013). Many more women delay childbirth into 40s due to career constraints. Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved from http://www.jsonline.com/news/health/many-more-women-delay-childbirth-into-40s-due-to-career-constraints-b9971144z1-220272671.html

American Pregnancy Association. (2015). Epidural anesthesia. Retrieved from http://americanpregnancy.org/labor-and-birth/epidural/

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5). Washington, DC: Author.

American Society of Reproductive Medicine. (2015). State infertility insurance laws. Retrieved from http://www.reproductivefacts.org/insurance.aspx

Berger, K. S. (2005). The developing person through the life span (6th ed.). New York: Worth.

Berk, L. (2004). Development through the life span (3rd ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon. 66

Betts, J. G., DeSaix, P., Johnson, E., Johnson, J. E., Korol, O., Kruse, D. H., Poe, B., Wise, J. A., & Young, K. A. (2019). Anatomy and physiology (OpenStax). Houston, TX: Rice University.

Bortolus, R., Parazzini, F., Chatenoud, L., Benzi, G., Bianchi, M. M., & Marini, A. (1999). The epidemiology of multiple births. Human Reproduction Update, 5, 179-187.

Bray, I., Gunnell, D., & Smith, G. D. (2006). Advanced paternal age: How old is too old? Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 60(10), 851-853. Doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.045179

Brazelton, T. B., & Nugent, J. K. (1995). Neonatal behavioral assessment scale. London: Mac Keith Press.

Bregel, S. (2017). The lonely terror of postpartum anxiety. Retrieved from https://www.thecut.com/2017/08/the-lonely-terror-of-postpartum-anxiety.html

Carrell, D. T., Wilcox, A. L., Lowry, L., Peterson, C. M., Jones, K. P., & Erikson, L. (2003). Elevated sperm chromosome aneuploidy and apoptosis in patients with unexplained recurrent pregnancy loss. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 101(6), 1229-1235.

Carroll, J. L. (2007). Sexuality now: Embracing diversity (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2005). Surgeon’s general’s advisory on alcohol use during pregnancy. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/fasd/documents/surgeongenbookmark.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Pelvic inflammatory disease. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/std/pid/stdfact-pid-detailed.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015a). Birthweight and gestation. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/birthweight.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015b) Genetic counseling. Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/genetics/genetic_counseling.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015c). Preterm birth. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pretermbirth.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015d). Smoking, pregnancy, and babies. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/campaign/tips/diseases/pregnancy.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016a). Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/fasd

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016b). HIV/AIDS prevention. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/prevention.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016c). HIV transmission. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/transmission.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016d). STDs during pregnancy. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/std/pregnancy/stdfact-pregnancy.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Pregnancy-related deaths. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/maternal-deaths/

Chiu, A. (2019, May 30). ‘She’s a miracle’: Born weighing about as much as ‘a large apple,’ Saybie is the world’s smallest surviving baby. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2019/05/30/world-smallest-surviving-baby-saybie-miracle/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.7c8d0bb6acf7 67

Conners, N.A., Bradley, R.H., Whiteside-Mansell, L., Liu, J.Y., Roberts, T.J., Burgdorf, K., & Herrell, J.M. (2003). Children of mothers with serious substance abuse problems: An accumulation of risks. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 29 (4), 743–758.

Cordier, S. (2008). Evidence for a role of paternal exposure in developmental toxicity. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology, 102, 176-181.

Eisenberg, A., Murkoff, H. E., & Hathaway, S. E. (1996). What to expect when you’re expecting. New York: Workman Publishing.

Figdor, E., & Kaeser, L. (1998). Concerns mount over punitive approaches to substance abuse among pregnant women. The Guttmacher report on public policy, 1(5), 3–5.

Fraga, M. F., Ballestar, E., Paz, M. F., Ropero, S., Setien, F., Ballestar, M. L., … Esteller, M. (2005). Epigenetic differences arise during the lifetime of monozygotic twins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (USA), 102, 10604-10609. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0500398102

Gottlieb, G. (1998). Normally occurring environmental and behavioral influences on gene activity: From central dogma to probabilistic epigenesis. Psychological Review, 105, 792-802.

Gottlieb, G. (2000). Environmental and behavioral influences on gene activity. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 9, 93-97.

Gottlieb, G. (2002). Individual development and evolution: The genesis of novel behavior. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gould, J. L., & Keeton, W. T. (1997). Biological science (6th ed.). New York: Norton.

Gregory, E. (2007). Ready: Why women are embracing the new later motherhood. Philadelphia, PA: Basic Books.

Grossman, D., & Slutsky, D. (2017). The effect of an increase in lead in the water system on fertility and birth outcomes: The case of Flint, Michigan. Economics Faculty Working Papers Series. Retrieved from http://www2.ku.edu/~kuwpaper/2017Papers/201703.pdf

Hall, D. (2004). Meiotic drive and sex chromosome cycling. Evolution, 58(5), 925-931. Health Resources and Services Administration. (2015). HIV screening for pregnant women. Retrieved from http://www.hrsa.gov/quality/toolbox/measures/hivpregnantwomen/index.html

Jos, P. H., Marshall, M. F., & Perlmutter, M. (1995). The Charleston policy on cocaine use during pregnancy: A cautionary tale. The Journal of Law, Medicine, and Ethics, 23(2), 120-128.

Leve, L. D., Neiderhiser, J. M., Scarmella, L. V., & Reiss, D. (2010). The early growth and development study: Using the prospective adoption design to examine genotype-interplay. Behavior Genetics, 40, 306-314. DOI: 10.1007/s10519-010- 9353-1

MacDorman, M., Menacker, F., & Declercq, E. (2010). Trends and characteristics of home and other out of hospital births in the United States, 1990-2006 (United States, Center for Disease Control). Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr58;nvsr58_11.PDF

Maier, S.E., & West, J.R. (2001). Drinking patterns and alcohol-related birth defects. Alcohol Research & Health, 25(3), 168-174.

March of Dimes. (2009). Rh disease. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/complications/rh-disease.aspx

March of Dimes. (2012a). Rubella and your baby. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/baby/rubella-and-your-baby.aspx 68

March of Dimes. (2012b). Stress and pregnancy. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/pregnancy/stress-and-pregnancy.aspx

March of Dimes. (2012c). Teenage pregnancy. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/materials/teenage-pregnancy.pdf

March of Dimes. (2012d). Toxoplasmosis. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/complications/toxoplasmosis.aspx

March of Dimes. (2013). Sexually transmitted diseases. Retrieved http://www.marchofdimes.org/complications/sexually-transmitted-diseases.aspx

March of Dimes. (2014). Pesticides and pregnancy. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/pregnancy/pesticides-and-pregnancy.aspx

March of Dimes. (2015a). Depression during pregnancy. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/complications/depression-during-pregnancy.aspx

March of Dimes. (2015b). Gestational diabetes. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/complications/gestational-diabetes.aspx

March of Dimes. (2015c). High blood pressure during pregnancy. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/complications/high-blood-pressure-during-pregnancy.aspx

March of Dimes. (2015d). Neonatal abstinence syndrome. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/complications/neonatal-abstinence-syndrome-(nas).aspx

March of Dimes. (2016a). Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/complications/fetal-alcohol-spectrum-disorders.aspx

March of Dimes. (2016b). Identifying the causes of birth defects. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/research/identifying-the-causes-of-birth-defects.aspx

March of Dimes. (2016c). Marijuana and pregnancy. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/pregnancy/marijuana.aspx

March of Dimes. (2016d). Pregnancy after age 35. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/pregnancy-after-age-35.aspx

March of Dimes. (2016e). Prescription medicine during pregnancy. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/pregnancy/prescription-medicine-during-pregnancy.aspx

March of Dimes. (2016f). Weight gain during pregnancy. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/pregnancy/weight-gain-during-pregnancy.aspx

Martin, J. A., Hamilton, B. E., Osterman, M., Curtin, S. C., & Mathews, T. J. (2015). Births: Final data for 2013. National Vital Statistics Reports, 64(1), 1-65.

Mayo Clinic. (2014). Labor and delivery, postpartum care. Retrieved from http://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/labor-and-delivery/ in-depth/inducing-labor/art-20047557

Mayo Clinic. (2015). Male infertility. Retrieved from http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/male-infertility/basics/definition/con-20033113

Mayo Clinic. (2016). Episiotomy: When it's needed, when it's not. Retrieved from http://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/labor-and-delivery/in-depth/episiotomy/art-20047282

Morgan, M.A., Goldenberg, R.L., & Schulkin, J. (2008) Obstetrician-gynecologists’ practices regarding preterm birth at the limit of viability. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine, 21, 115-121.

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2013). Preeclampsia. Retrieved from https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/preeclampsia/conditioninfo/Pages/risk.aspx 69

National Institute of Health (2015). An overview of the human genome project. Retrieved from http://www.genome.gov/12011238

National Institute of Health. (2019). Klinefelter syndrome. Retireived from https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/klinefelter- syndrome#statistics

National Public Radio. (Producer). (2015, November 18). In Tennessee, giving birth to a drug-dependent baby can be a crime [Audio podcast]. Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/templates/transcript.php?storyld=455924258

Nippoldt, T.B. (2015). How does paternal age affect a baby’s health? Mayo Clinic. Retrieved from http://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/getting-pregnant/expert-answers/paternal-age/faq- 20057873

Pettersson, E., Larsson, H., D’Onofrio, B., Almqvist, C., & Lichtenstein, P. (2019). Association of fetal growth with general and specific mental health conditions. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(5), 536-543. Doi:10.1001jamapsychiatry.2018.4342

Plomin, R., DeFries, J. C., Knopik, V. S., & Niederhiser, J. M. (2013). Behavioral genetics (6th edition). NY: Worth Publishers.

Poduri, A., & Volpe, J. (2018). Volpe’s neurology of the newborn (6th edition). Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier.

Regev, R.H., Lusky, T. Dolfin, I. Litmanovitz, S. Arnon, B. & Reichman. (2003). Excess mortality and morbidity among small-for-gestational-age premature infants: A population based study. Journal of Pediatrics, 143, 186-191.

Rehan, V. K., Sakurai, J. S., & Torday, J. S. (2011). Thirdhand smoke: A new dimension to the effects of cigarette smoke in the developing lung. American Journal of Physiology: Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology, 301(1), L1-8.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (1997). Fetal awareness: Review of research and recommendations. Retrieved from https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/guidelines-research-services/guidelines/fetal-awareness---review-of-research-and-recommendations-for-practice/

Someji, S., & Beltrán-Sánchez, H. (2019). Association of maternal cigarette smoking and smoking cessation with preterm birth. JAMA Network Open, 2(4), e192514. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2514

Stiles, J. & Jernigan, T. L. (2010). The basics of brain development. Neuropsychology Review, 20(4), 327-348. doi: 10.1007/s11065-010-9148-4

Streissguth, A.P., Barr, H.M., Kogan, J. & Bookstein, F. L. (1996). Understanding the occurrence of secondary disabilities in clients with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) and Fetal Alcohol Effects (FAE). Final Report to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), August. Seattle: University of Washington, Fetal Alcohol & Drug Unit, Tech. Rep. No. 96-06.

Sun, F., Sebastiani, P., Schupf, N., Bae, H., Andersen, S. L., McIntosh, A., Abel, H., Elo, I., & Perls, T. (2015). Extended maternal age at birth of last child and women’s longevity in the Long Life Family Study. Menopause: The Journal of the North American Menopause Society, 22(1), 26-31.

Tong, V. T., Dietz, P.M., Morrow, B., D'Angelo, D.V., Farr, S.L., Rockhill, K.M., & England, L.J. (2013). Trends in smoking before, during, and after pregnancy — Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, United States, 40 Sites, 2000–2010. Surveillance Summaries, 62(SS06), 1-19. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ss6206a1.htm

United States National Library of Medicine. (2014). In vitro fertilization. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/007279.htm

United States National Library of Medicine. (2015a). Fetal development. Retrieved from https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/002398.htm

United States National Library of Medicine. (2015b). Neonatal respiratory distress syndrome. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/001563.htm 70

World Health Organization. (2010, September 15). Maternal deaths worldwide drop by a third, WHO. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/ 2010/maternal_mortality_20100915/en/index.html

Youngentob, S. L., Molina, J. C., Spear, N. E., & Youngentob, L. M. (2007). The effect of gestational ethanol exposure on voluntary ethanol intake in early postnatal and adult rats. Behavioral Neuroscience, 121(6), 1306-1315. doi.org/10.1037/0735-7044.121.6.1306

OER Attribution:

"Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective, Second Edition" by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0

Video Attributions:

How in vitro fertilization (IVF) works by TED is licensed CC BY–NC–ND 4.0

How racism harms pregnant women - and what can help by TED is licensed CC BY–NC–ND 4.0

Media Attributions

- waterski © Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Sperm-egg © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Human_Fertilization © Ttrue12 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Human_Embryo_-_Approximately_8_weeks_estimated_gestational_age © Lunar Caustic is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- prenataldev © Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- criticalperiods © Laura Overstreet is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Photo_of_baby_with_FAS © Teresa Kellerman is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- catbox © Tom Thai is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- camylla-battani-son4VHt4Ld0-unsplash © Camylla Battani is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Hazardous-pesticide © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- APGAR_score © Dr.Vijaya chandar is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Human_Infant_in_Incubator © Zerbey at the English language Wikipedia is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- saybie3jpeg