Vocational Development

Heather Brule and Ellen Skinner

Learning Objectives: Vocational Development

- Define the primary task of vocational choice.

- What are the main theories (and underlying meta-theories) describing vocational development?

- What are the three periods of vocational development?

- What are the substages of the last period?

- What are the main factors that influence vocational decision making?

- What is the role of personality and vocational interests?

- What is the role of families?

- What is the role of societal and cultural factors?

- How is vocational decision making different for youth who are not college bound?

A primary task of early adulthood is vocational choice. The process of defining occupational goals and launching a career are challenging, and involve a whole series of decisions and actions that culminate in most people settling into a job or profession sometime during their twenties. Like so many developmental processes, this one starts at a very young age, proceeds through several typical steps, and can take a variety of pathways. Work represents a crucial life domain, and plays an important role all during middle and late adulthood, potentially influencing psychological and economic well-being, sense of purpose, cognitive and social development, and how the psychosocial task of generativity versus stagnation will be negotiated during middle adulthood.

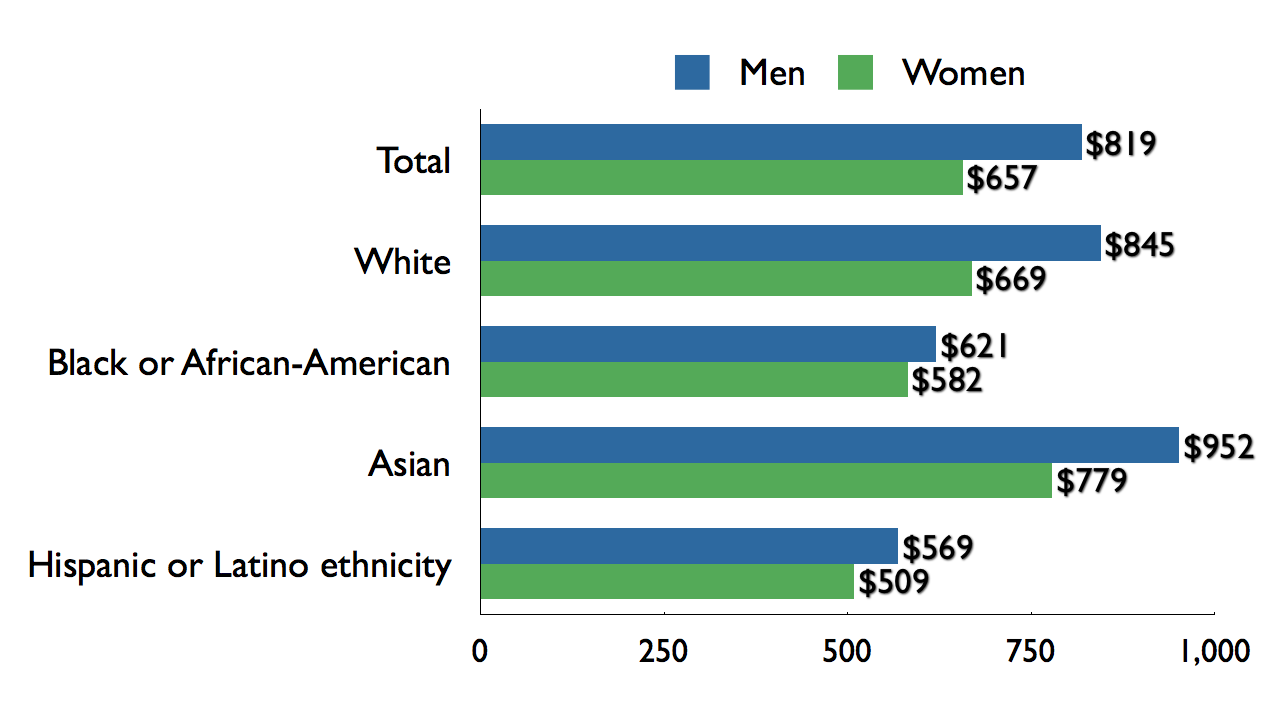

As young adults will tell you, it can be challenging to find meaningful work that (1) fits well with your own passions and strengths; (2) allows you to independently support yourself; and (3) can be integrated with other commitments, like family, friends, children, and recreational pastimes. Many factors at the personal, interpersonal, and societal levels contribute to this process, and make vocational decision-making easier or harder. Many young people are confronted with discrimination and exclusion as they negotiate this process. Status hierarchies organized around class, ethnicity, gender, and other socially-assigned categories produce inequities in college attendance, employment opportunities, and levels of pay. Macrosystem factors, like historical changes in the cost of college, the national economic outlook (e.g., the Great Recessions of 2008 and 2020), and the changing job market, also play big roles. For example, compared to their grandparents, youth of today are much more likely to hold multiple kinds of jobs over their lifetimes, making vocational development more than ever a lifelong process.

Development of Vocational Decision-making

Like many aspects of identity development, selecting a work role is a gradual process that begins in early childhood. It is complex and includes factors highlighted by multiple meta-theories: (1) as suggested by maturational meta-theorists, it involves people’s intrinsic interests and talents; (2) consistent with mechanistic metatheories, it is also shaped by processes of social learning and socialization (i.e., expectations, demands, and rewards of the local and distal social context); and (3) as organismic meta-theories remind us, the cognitive processes employed by children youth, and young adults show qualitative shifts, meaning that their understanding, decision making, and participation in this process show regular age-graded changes. Hence, a contextual lifespan developmental approach which incorporates all these factors, as well as the historical and social forces mentioned previously, provides a good framework for thinking about processes of vocational development. Major theories hold that children and youth normatively move through three age-graded periods along this pathway (Gottfredson, 2005; Super, 1990, 1994).

- Fantasy period. Starting in early childhood, young children become aware of the world of work, and the options and status connected to particular vocations. Across early and middle childhood, children explore job options largely through imagination and fantasy (Howard & Walsh, 2010). Using pretend play, stories, discussions about the future, and even their choice of Halloween costumes, young children try out a variety of occupations, selecting ones with which they are familiar that sound exciting and fun. In answer to the question “What do you want to be when you grow up?”, young children are likely to name the jobs held by their families and neighbors, or exciting or high-status jobs, like firefighter and rock star. But they are just as likely to select imaginary options, like superhero, dragon keeper, or quidditch player. For most young children, these initial preferences provide a window on the child’s socialization experiences and have little to do with the decisions they will eventually make.

Preparing Young Children for the World of Work

Two ways that parents can help prepare young children for the world of work are (1) encouraging them to help out with chores around the house starting when they are toddlers, and (2) giving them their own money to manage in the form of an allowance, starting at the age of 3 or 4 years old. Many middle class parents underestimate children’s ability to participate fully in these activities at such young ages, but if parents have the patience to allow toddlers to really help out when they are most interested in doing so, they can reap the reward of children’s continuing willingness and pride in taking on family responsibilities, as described in this article on How to Get your Kids to Do Chores. And if children manage their own allowances starting at a young age, they learn more quickly about saving money and making informed decisions about spending.

- Tentative period. Starting at the end of middle childhood, with the onset of formal operations, adolescents begin to understand vocational decision making in more complex ways. Between the ages of 11 and 16, as young adolescents are working on the task of identity development more generally, they begin to think about their own part in the vocational equation: (1) what they like to do (i.e., their interests, passions, and values); and (2) what they are good at. Advances in cognition at this age bring with it an increased capacity for social comparison, and youth begin to evaluate how their skills and abilities in specific areas stack up compared to those of their agemates. Increasing understanding of the requirements of certain jobs provides a template for understanding whether particular vocational pathways are likely to be options for them. Unfortunately, this is the same age at which messages from teachers and from society at large (about who is smart enough or good enough at math and science) can discourage youth (especially young women and adolescents from ethnic minority backgrounds) from pursuing careers that require advanced training or degrees. In conversations with youth about their future careers, parents and other adults can hear the complexity of their considerations. For example, at the end of high school Leona says, “On the one hand, I really do love music, writing songs is such a comfort when I’m down. I can play 3 or 4 instruments and I want to play in a band forever. On the other hand, I sure enjoy kids, babysitting is such fun. I wish all kids could make music together. Maybe I’ll be a music teacher or work at the Rock and Roll Camp for Girls.”

- Realistic period. Starting in their late teens and early twenties, youth consolidate their own side of the vocational equation (i.e., their interests, abilities, and values), and begin figuring out how these fit with the occupational options provided in their geographic region. Society’s side of the vocational equation is grounded in hard practical and economic realities of the job market: what kinds of work society will pay you to do. During this period, youth learn about the categories of jobs that are available, how hard they are to get, and the qualifications needed to be eligible for specific careers. Some of these realizations come from the school of hard knocks, as teenagers look at the jobs that their family members and neighbors hold and as they themselves apply for summer or after-school jobs. This is the period of vocational development when occupational search begins in earnest.

A first step during this period is further exploration, when youth gather more information about how a range of potential careers might align with their personal preferences. If young adults are in college (about 70% of high school graduates enroll), this might include taking a variety of courses that interest them to investigate potential majors, talking to other students and career advisors, joining clubs and participating in extracurricular activities, seeking out internships, or volunteering at nonprofits or other organizations. In the final phase, crystallization, young adults settle on a general occupational category, and then experiment further until they decide on a specific job (Stringer, Kerpelman, & Skorikov, 2011).

The Realistic period can be discouraging for youth from low income and ethnic minority families, who may encounter diminished educational and employment opportunities, and discrimination in college admissions and hiring. Status hierarchies organized around class (wealth and education, or socioeconomic status, SES) mean that the processes of vocational choice differ markedly between youth from rich and poor backgrounds. Some young people from low-wealth backgrounds do not have the privilege of attending college or exploring career options. Many work throughout high school and once they graduate, they need to get whatever full-time jobs they can to help support their families. For some youth who live in economically depressed areas (e.g., some rural regions or Native reservations), these dawning realizations may lead them to leave their families for cities or regions with greater economic opportunities.

Career opportunities for people of color may be limited by societal expectations and discrimination in areas ranging from guidance counseling and hiring to professional networking, mentorship and promotion, with the result that Black and Hispanic people, along with other groups of people of color, are under-represented in higher-status and higher-paying jobs (Hotchkiss & Borow, 1990; Walsh et al, 2001; Worthington, Flores, & Navarro, 2005). The intersectionality between class and ethnicity is particularly pronounced in vocational development: On one hand, SES plays a large role, in that disparities in educational quality due to inadequate school funding directly inhibit career choices. On the other hand, some of the most pronounced ethnic differences in employment and opportunities are actually found when comparing members of different ethnic groups who are of a similar SES – those who are college-educated, or middle-class, for example (e.g., Wilson, Tienda, and Wu, 1995).

Just like identity development, vocational decision-making can be re-opened at later ages for any number of reasons: dissatisfaction with a current line of work, lay-offs or recessions, geographical relocation, emergence of new job sectors, or changes in other life domains (e.g., divorce or birth of a child). These changes can initiate additional rounds of vocational decision making, including reflection about one’s interests, talents, and values, exploration of alternative possible career choices, and identification of new lines of work. When such decision-making takes place during middle age, job seekers may be especially attuned to the ways in which careers allow them to engage with the developmental task of generativity. That is, middle-age people may focus especially on issues of value, meaning, and purpose, so they can find career pathways that allow them to mentor and guide others, and make lasting contributions to society.

Factors that Influence Vocational Decision-making

Although most youth proceed along the normative path of vocational development described above, other pathways are possible. Some young people identity their chosen profession at a very young age (often following in familial footsteps) and directly pursue that goal all throughout high school and college. Others make up and then change their minds multiple times, even going so far as to start different careers before figuring out what is right for them, while others remain undecided for long periods of time, and may support themselves with a series of low level jobs while they make progress on this task. Others may pick a calling for which society provides little remuneration (e.g., artist or social activist) and then find ways to support themselves on the side. Young people who attend college are provided additional time and scaffolding, since college is designed to help students learn about their own interests and values, and gain knowledge and credentials relevant to specific vocations. Youth from lower SES families may have fewer choices and feel more pressure to begin work as soon as possible, making it more difficult for them to attend college or explore vocational options.

Although vocational choice is considered to be the result of decision-making processes, it is important to emphasize that discerning one’s vocation is not a cold calculation, in which people rationally weigh their skills, interest, and values against multiple job options to come up with the “logical choice.” Instead vocational development is a process that is deeply entwined with identity development, and so includes dimensions focused on meaning, value, motivation, emotion, and social relationships. It is a task that is actively negotiated and can be fraught with confusion, anxiety, and frustration. The extent to which this task will progress in a positive direction depends on a wide variety of individual, social, and societal factors.

Vocational Interests and Personalities

People are drawn to particular vocations based on the fit between their own interests (or vocational personalities) and the nature of specific work environments. One of the most influential theories of vocational personalities was developed by John Holland (Holland, 1985, 1997). It was introduced in 1959 (Holland, 1959) and is still in use in many areas today, such as career counseling (Nauta, 2010; Click here to view article). The theory’s core idea is that people typically fall into one of six “vocational personality” types, each of which is characterized by a profile of interests, preferred activities, beliefs, abilities, values, and characteristics. These interest profiles can be used to identify the kinds of jobs that might be a good match for people with different vocational personalities. It is important to note that many people have more than one set of interests, and would do well in a variety of professions (Holland, 1997; Spokane & Cruza-Guet, 2005).

- Realistic. People who like solving real world problems; working with their hands; building, fixing, or making things; and operating equipment, tools or machines. May be a good fit for mechanical and manual occupations like engineering, electrician, horticulturist, or farmer.

- Investigative. People who like to discover and research ideas; observe, investigate and experiment; ask questions and solve problems. May be a good fit for science, research, journalism, medical and health occupations.

- Artistic. People who enjoy creating or designing things; using art, music, writing, or drama to express themselves; and communicate or perform. Often a good fit to choose occupations in the creative arts, writing, photography, design.

- Social. People who like people and are concerned for others’ well-being and welfare; and like working with others to teach, train, inform, help, treat, heal, cure, and serve. May be most comfortable in helping or human service professions, like teaching, social work, or counseling.

- Enterprising. People who are adventurous; and like meeting, leading, and influencing others; like planning and strategizing. Are drawn to business, management, supervisory positions, sales, or politics.

- Conventional. People who enjoy working indoors at tasks that involve organizing, following procedures, working with data or numbers, planning work and events. May be good fit for fields like business, librarian, office worker, or computer operator.

If you would like to see where you fall on these personality types, you can take Holland’s assessment on the Bureau of Labor’s webpage: https://www.mynextmove.org/explore/ip

Occupational decisions are based, not only on people’s interests and values, but also on other factors in their lives, such as financial circumstances, familial influences, and current educational and job opportunities. For example, during the Great Recession that started in 2008, many people who could not find work decided to attend to college and gained additional skills and qualifications. During that same time period, presumably based on economic uncertainty, more undergraduates opted to major in occupational sectors showing job growth and higher salaries, like business, the natural sciences, computing, and engineering (U.S, Department of Education, 2012).

Familial Influences

Families pave the way for their children’s vocational choices, starting before they are born. One of the most important predictors of a young adult’s eventual occupation is the SES of their family of origin. Children from high SES backgrounds have more and better educational opportunities, in the form of higher quality schools with better academic programs, more enrichment activities (e.g., extracurricular activities, clubs, and summer camps focused on topics like science, engineering, computer programming, and robotics), greater access to better quality higher education, and better networks of social capital for seeking internships and jobs (Kalil, Levine, & Ziol-Guest, 2005).

Parents with more wealth and education (and especially mothers with more education) confer a host of advantages on their offspring and these eventually translate into better academic performance at all levels of school, which is one of the strongest predictors of occupational attainment. Families also influence vocational decision-making processes indirectly by the status and range of occupations they model, as well as directly by trying to persuade youth to consider or follow specific career pathways. High SES families also buffer their offspring when young people chose sporadic employment or low paying professions (e.g., artist, musician) by financially subsidizing their career choices.

Parenting style. Research on parenting styles suggests that authoritative parenting provides the greatest support for constructive vocational decision-making since it both encourages youth to discover their own interests and passions, while also helping them develop tools like self-discipline and achievement orientations that will enable them to make progress along their chosen route. Authoritarian parenting, with its rigid demands for obedience and compliance, may interfere with exploratory efforts and lead to premature foreclosure on parentally-specified options. These heavy-handed tactics may sometimes lead to higher occupational attainment (as seen, for example, in some Asian-American or Jewish families) but they can also undermine some of the long-term development fostered by career choices that are a better match for individuals’ interests and proclivities. In other cases, family obligations may lead students to drop out in order to help with financial support (as seen in some Latinx youth, who as a group have the lowest educational attainment but the highest rates of employment of all racial/ethnic groups). Permissive parenting may interfere with young people’s capacities to come to terms with the realities of the job market and delay decision making, whereas neglectful parenting robs youth of the support and scaffolding they need for constructive exploration and decision making, and so may contribute to unemployment or sporadic employment in low skilled jobs.

Upward social mobility. In general, children and youth tend to prefer the kinds of occupations that they see in their parents and neighbors. As a result, youth from high SES families are more likely to prefer and pursue high-status white color professions, such as medicine, law, or academia, whereas those from low SES families are more likely to favor and go into blue collar careers, some of which are high skill (like plumbing, electrician, preschool teacher) and some of which are low skill (food service worker, cashier, delivery driver), but all of which have a lower pay scale. The correspondence in occupations between parents and children is only partly a function of familiarity, persuasion, and similarity in personality and interests (Ellis & Bonin, 2003; Schoon & Parsons, 2002). It also reflects the extent to which high and low SES families can “launch” children into higher status careers.

All parents can foster high educational and occupational aspirations. Over and above the effects of SES, career attainment is predicted by parental guidance, high demands and expectations to succeed in school, and pressure toward high-status jobs (Bryant, Zvonkovic, & Reynolds, 2006; Stringer & Kerpelman, 2010). In a process called upward mobility, a young person can break out of the SES level of their family of origin, as seen for example, in the great success of many first generation college students. Based on multiple societal trends, however, upward social mobility has gotten increasingly difficult over the last several decades.

Societal and Cultural Factors

Many of the factors that are typically described as “family influences” on vocational decision making also reflect powerful societal and political forces that shape young people’s educational and occupational opportunities. For example, trends in politics and business have reduced well-paying employment opportunities in the blue collar sector over the last several decades. These trends include the loss of manufacturing jobs, increases in automation, the growth of the information economy, the stagnation of the minimum wage, weakening or breaking up unions, economic recessions and patterns of unemployment or underemployment that disproportionately disadvantage low SES and minority workers.

Alternative societal decisions would make it much easier for young people to find meaningful work and to be able to support themselves and their families on their wages. Successful strategies employed in other countries include policies designed to promote job growth, reduce income inequality, provide access to free high-quality higher education and job (re)training, maintaining the minimum wage at a level that keeps up with the cost of living, subsidizing child care, and making sure that healthcare is free or affordable and not tied to specific jobs. These decisions influence the vocational options (and quality of life) open, not only to young people entering the job market, but to workers all across the lifespan.

Teacher Support and Encouragement

Many youth who go on to careers that require prolonged education or training report that their vocational decision making process was influenced by their teachers. During high school or college, their teachers took a special interest, and mentored or otherwise encouraged them to continue along certain occupational pathways (Bright et al., 2005; Reddin, 1997). High school students that go on to college tend to have more positive connections with teachers than non-college-bound students, and such close relationships promote higher career aspirations, especially in young women (Wigfield et al., 2002). Such connections are especially important to first generation students and students from underrepresented minority backgrounds who may not have many role models in their immediate family.

Gender Stereotypes

Gender disparities in occupational status and income have steadily decreased over the last several decades, as more and more women enter the labor force. Gender-role attitudes are changing, and girls show greater interest in male-dominated professions, but progress has been slow. Although girls typically outperform boys academically all throughout school, and graduate from college at higher rates (both overall and within every racial/ethnic group), they reach high school less confident in their academic competence, more likely to underestimate their achievement, and less interested in careers in mathematics, natural science, and engineering (Ceci & Williams, 2010; Parker et al., 2012). During college, many women’s career aspirations further decline as they worry about their capacity to succeed in challenging classes and careers in science and mathematics, and wonder whether they will be able to combine a high-powered career with responsibilities of children and families (Chhin, Bleeker, & Jacobs, 2008; Wigfield et al., 2006)

Women are still concentrated in a subset of college majors and in lower-status and less-well-paid occupations (US Census Bureau, 2019). Untangling this problem requires a two-fold solution. First, high school and college teachers must be sensitized to the roadblocks, discrimination, and prejudice girls and women face based on entrenched myths about their natural aptitude for male dominated subjects and professions. To reverse internalized biases, girls and women would also benefit from some support in reworking these narratives to counteract their own concerns and insecurities. Many programs are now in place to increase the participation and success of women and ethnic minority students in STEM fields. These programs typically include active recruitment, mentoring, creation of supportive peer cohorts, and guided research experiences, and have been somewhat successful at increasing graduation rates for some subgroups of students.

A second correction to gender disparities in income involves improving the status and salary levels for traditionally female occupations, like childcare, eldercare, teaching, social work, and nursing. These occupations are of great benefit to society, yet workers are not paid in ways commensurate with this value. Society needs to reexamine its priorities, when someone who trades in financial markets where nothing of value is produced are paid hundreds of times more than people whose dedication keeps premature infants alive or supports the frail elderly during their twilight years.

Compared to women, men have changed little in their occupational choices; few pursue nontraditional careers, such as nursing or teaching elementary school. Those who do are less gender-typed, more liberal in their social attitudes, less concerned with social status, and more interested in working with and helping people (Dodson & Borders, 2006; Jome, Surething, &Taylor, 2005). Men in non-traditional careers generally report high satisfaction in their work, but also note that they have to deal with biases and stigma about their decisions to pursue lower-status occupations, especially from other men.

Non-College-Bound Youth

According to the US Census, the highest level of education completed by 28.1% of the labor force (i.e., population age 25 and older) is high school, whereas 22.5% finished four years of college. Rates vary significantly by race/ethnicity: According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, the share of the labor force with at least a high school diploma was more than 90% each for Whites, Blacks, and Asians; but 76% for Hispanics. And 63% of Asians in the labor force had a bachelor’s degree and higher, compared with 41% of Whites, 31% of Blacks, and 21% of Hispanics.

As a result, approximately one-third of young people who graduate high school do not go to college. This decision has a big impact on their career options. Most of them find it difficult to secure a job other than the ones they held during high school. Although high school graduates are more likely to find employment than young people who dropped out of high school, they have fewer occupational opportunities than their counterparts from earlier cohorts. During times of recession, those prospects worsen as positions that become available are taken by (sometimes overqualified) college graduates. Before the recession created by the pandemic in 2020, unemployment rates for 24-35 year-olds who dropped out of high school were about 43%; for those who graduated high school about 26%, and for those who graduated college about 13% (National Center for Education Statistics).

The discouraging prospects of non-college bound youth are also a product of societal decisions about the educational and occupational tracks available in US schools. In contrast, Germany, Austria, Denmark, Switzerland, and several Eastern European countries have intentionally created national apprenticeship programs that facilitate the transition from high school to work. For example, about two-thirds of German students do not attend college preparatory high schools. Instead, starting in middle school, they head down a vocational track toward one of the most successful work-study apprenticeship programs for entering business and industry in the world. At age 15 or 16, during the last two years of compulsory education, they begin a program that combines part-time vocational courses with an apprenticeship that is jointly sponsored by educators and employers (Deissinger, 2007). Students who finish the program and pass a qualifying exam are certified as skilled workers and enter occupations whose wages are set and protected by unions.

Industries provide funding for these apprenticeship programs because it is clear that they provide a dependable supply of motivated and skilled workers (Kerckhoff, 2002). In addition, such programs encourage students to stay in school and allow young people to begin productive work lives directly after high school. Providing a pipeline between the worlds of school and work not only benefits youth themselves, but also provides value to the rest of society by contributing to national economic growth. To date, only small-scale work-study programs are attempting to bridge this gap in the US, but larger scale national programs are needed.

Vocational development is an important task for young adults, but the process of defining occupational goals and launching a career are challenging. Young people know that their occupational choices can have lifelong consequences. Jobs are sources of income and so influence living conditions and recreational options; they are how people spend much of their time and so fill their waking hours; workplaces can become extended “neighborhoods” or “families;” and they can provide a source of meaning and identity. No wonder young people may feel that the stakes are high. To constructively negotiate this task, they need the support of family, schools, workplaces, and the larger society.

Supplemental Materials

- This Ted Talk inspires young folks to get involved with acitvist work, through the story of one young woman’s work against child soldiers.

- This video details university students’ resistance to Hitler’s Nazi Germany.

- This article illustrates a Participatory Action Research initiative that examines the experiences of students with disabilities as they transition to college.

- This book defines the concept of White Immunity, as it relates to structural racism and the context of college campuses. Cabrera utilizes interviews with White, male students to bring forth the myth of post-racial higher education.

- This Ted Talk discusses how to create an inclusive college classroom that supports students of color and reduces imposter syndrome.

- This article discusses college campus racial climate and how microaggressions play a key role.

References

Bright, J. E., Pryor, R. G., Wilkenfeld, S., & Earl, J. (2005). The role of social context and serendipitous events in career decision making. International journal for educational and vocational guidance, 5(1), 19-36.

Bryant, B. K., Zvonkovic, A. M., & Reynolds, P. (2006). Parenting in relation to child and adolescent vocational development. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69(1), 149-175.

Ceci, S. J., & Williams, W. M. (2009). The mathematics of sex: How biology and society conspire to limit talented women and girls. New York: Oxford University Press.

Chhin, C. S., Bleeker, M. M., & Jacobs, J. E. (2008). Gender-typed occupational choices: The long-term impact of parents’ beliefs and expectations. In H. M. Watt & J. S. Eccles (Eds.), Gender and occupational outcomes: Longitudinal assessments of individual, social, and cultural influences. Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Deissinger, T. (2007). “Making schools practical”: Practice firms and their function in the full-time vocational school system in Germany. Education+ Training, 49, 364-378.

Dodson, T. A., & Di Borders, L. A. (2006). Men in traditional and nontraditional careers: Gender role attitudes, gender role conflict, and job satisfaction. The Career Development Quarterly, 54(4), 283-296.

Ellis, L., & Bonin, S. L. (2003). Genetics and occupation-related preferences. Evidence from adoptive and non-adoptive families. Personality and Individual Differences, 35(4), 929-937.

Gottfredson, L. S. (2005). Applying Gottfredson’s theory of circumscription and compromise in career guidance and counseling. Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work, (p. 71-100). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Holland, J. L. (1959). A theory of vocational choice. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 6, 35–45.

Holland, J. L. (1985). Making vocational choices: A theory of vocational personalities and work environments. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prencice-Hall.

Holland, J. L. (1997). Making vocational choices: A theory of vocational personalities and work environments (3rd ed.). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Hotchkiss, L., & Borow, H. (1990). Sociological perspectives on career choice and attainment. In D. Brown, L. Brooks & Associates (Eds.), Career choice and development (2nd ed., pp. 137–168). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Howard, K. A., & Walsh, M. E. (2010). Conceptions of career choice and attainment: Developmental levels in how children think about careers. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 76(2), 143-152.

Jome, L. M., Surething, N. A., & Taylor, K. K. (2005). Relationally oriented masculinity, gender nontraditional interests, and occupational traditionality of employed men. Journal of Career Development, 32(2), 183-197.

Kalil, A., Levine, J.A., & Ziol-Guest, K. M. (2005). Following in their parents’ footsteps: How characteristics of parental work predict adolescents’ interest in parents’ working jobs. In B. Schneider & L. J. Waite (Eds.), Being together, working apart: Dual-career families and the work-life balance (pp. 422-442). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kerckhoff, A. C. (2002). The transition from school to work. In J. T. Mortimer & R. Larson (Eds.), The changing adolescent experience: Societal trends and the transition to adulthood, (pp. 52-87). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Nauta, M. M. (2010). The development, evolution, and status of Holland’s theory of vocational personalities: Reflections and future directions for counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57(1), 11-22.

Nauta, M. M. (2010). The development, evolution, and status of Holland’s theory of vocational personalities: Reflections and future directions for counseling psychology. Journal of counseling psychology, 57(1), 11.

Parker, P. D., Schoon, I., Tsai, Y. M., Nagy, G., Trautwein, U., & Eccles, J. S. (2012). Achievement, agency, gender, and socioeconomic background as predictors of postschool choices: A multicontext study. Developmental psychology, 48(6), 1629-1642.

Reddin, J. (1997). High-achieving women: Career development patterns. In H. S. Farmer (Ed.), Diversity and women’s career development (pp. 95-126). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Schoon, I., & Parsons, S. (2002). Teenage aspirations for future careers and occupational outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 60(2), 262-288.

Spokane, A. R., & Cruza-Guet, M. C. (2005). Holland’s theory of vocational personalities in work environments. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work, (pp. 24-41). Hoboken, NK: Wiley.

Stringer, K., Kerpelman, J., & Skorikov, V. (2011). Career preparation: A longitudinal, process-oriented examination. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(1), 158-169.

Super, D. E. (1990). A life-span, life-space approach to career development. In D. Brown & L. Brooks, The Jossey-Bass management series and The Jossey-Bass social and behavioral science series. Career choice and development: Applying contemporary theories to practice (p. 197–261). Jossey-Bass.

Super, D. E. (1994). A life span, life space perspective on convergence. In M. L. Savikas & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Convergence in career development theories: Implications for science and practice (p. 63–74). CPP Books.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2019). Educational attainment in the United States: 2018. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2018/demo/education-attainment/cps-detailed-tables.html

U.S. Department of Education (2012). Digest of education statistics: 2011. Washington, DC: U.S. Government printing office. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2012/2012001.pdf

Walsh, W. B., Bingham, R. P., Brown, M. T., & Ward, C. M. (2001). Career counseling for African Americans. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Wigfield, A., Battle, A., Keller, L. B., & Eccles, J. S. (2002). Sex differences in motivation, self-concept, career aspiration, and career choice: Implications for cognitive development. In A. McGillicuddy-De Lisi &R. De Lisi (Eds.), Biology, society, and behavior: The development of sex differences in cognition (pp. 93-124). Westport, CT: Ablex.

Wigfield, A., Eccles, J. S., Schiefele, U., Roeser, R. W., & Davis‐Kean, P. (20076. Development of achievement motivation. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol 3. Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., pp. 933-1002). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Wilson, F. D., Tienda, M., & Wu, L. (1995). Race and unemployment: Labor Market experiences of black and white men, 1968–1988. Work and Occupations, 22, 245–270.

Worthington, R. L., Flores, L. Y., & Navarro, R. L. (2005). Career Development in Context: Research with People of Color. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (p. 225–252). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

OER Attribution:

“Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective, Second Edition” by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0

Video Attributions:

Being young and making an impact by TED is licensed CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0

The secret student resistance to hitler by TED is licensed CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0

How students of color confront imposter syndrome by TED is licensed CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0

Media Attributions

- US_gender_pay_gap,_by_sex,_race-ethnicity-2009 © Sonicyouth86 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license