Chapter Three: Reflecting on an Experience

One of my greatest pleasures as a writing instructor is learning about my students’ life journeys through their storytelling. Because it is impossible for us to truly know anything beyond our own lived experience,1 sharing our stories is the most powerful form of teaching. It allows us a chance to learn about others’ lives and worldviews.

Often, our rhetorical purpose in storytelling is to entertain. Storytelling is a way to pass time, to make connections, and to share experiences. Just as often, though, stories are didactic: one of the rhetorical purposes (either overtly or covertly) is to teach. Since human learning often relies on experience, and relating an experience constitutes storytelling, narrative can be an indirect teaching opportunity. Articulating lessons drawn from an experience, though, requires reflection.

Reflection is a way that writers

look back in order to

look forward.

Reflection is a rhetorical gesture that helps you and your audience construct meaning from the story you’ve told. It demonstrates why your story matters, to you and to the audience more generally: how did the experience change you? What did it teach you? What relevance does it hold for your audience? Writers often consider reflection as a means of “looking back in order to look forward.” This means that storytelling is not just a mode of preservation, nostalgia, or regret, but instead a mechanism for learning about ourselves and the world.

Chapter Vocabulary

|

Vocabulary |

Definition |

|

a rhetorical gesture by which an author looks back, through the diegetic gap, to demonstrate knowledge or understanding gained from the subject on which they are reflecting. May also include consideration of the impact of that past subject on the author’s future—“Looking back in order to look forward.” |

|

|

from “diegesis,” the temporal distance between a first-person narrator narrating and the same person acting in the plot events. I.e., the space between author-as-author and author-as-character. |

|

Techniques

“Looking back in order to look forward,”2 or

“I wish that I knew what I know now when I was younger”3

As you draft your narrative, keep in mind that your story or stories should allow you to draw some insight that has helped you or may help your reader in some way: reflection can help you relate a lesson, explore an important part of your identity, or process through a complicated set of memories. Your writing should equip both you and your audience with a perspective or knowledge that challenges, nuances, or shapes the way you and they interact with the world. This reflection need not be momentous or dramatic, but will deepen the impression of your narrative.

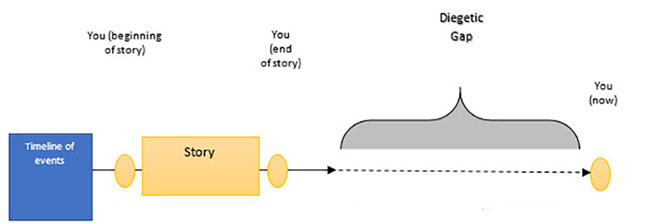

Reflection relies on what I call the diegetic gap. Diegesis is a term from the field of narratology referring to narration—the story as it is portrayed. In turn, this gap identifies that time has passed between the plot events and your act of writing. Simply put, the diegetic gap is the distance between you-the-author and you-the-character:

Because we are constantly becoming ourselves, shaped by our relationships and experiences, “you” are a different person at all three points. By looking back at your story, you can cultivate meaning in ways you could not during the events or immediately following them. Distance from an event changes the way we see previous events: time to process, combined with new experiences and knowledge, encourages us to interpret the past differently.

As you’ll see in the upcoming activities , looking back through this gap is a gesture akin to the phrase “When I look back now, I realize that…”4

Wrap-up vs. Weave

Students often have a hard time integrating reflective writing throughout their narratives. In some cases, it is effective to use reflection to “wrap up” the story; it might not make sense to talk about a lesson learned before the story has played out. However, you should try to avoid the “tacked on” paragraph at the end of your story: if your reflective writing takes over at the end of the story, it should still feel like a part of the narrative rather than an afterthought. In other words, you should only reserve your reflective writing for the last paragraph or two if the story has naturally and fluidly brought us across the diegetic gap to present day.

Instead of a wrap-up, though, I often challenge my students to weave their reflection in with the story itself. You can see this at work in “Slowing Down” and “Parental Guidance” in some places. However, to see woven reflection applied even more deliberately, take a look at the model text “Blood & Chocolate Milk.” This author explicitly weaves narration and reflection; while your weave doesn’t need to be this obvious, consider how the author’s choices in this essay enhance both the narrative and your understanding of their family dynamic.

Spelling it Out vs. Implying Meaning

Finally, you should be deliberate about how overt you should make your reflection. If you are trying to connect with your reader, sharing your story so they might

better know you, the world you live in, or even themselves, you need to walk the fine line between subtlety and over-explanation. You need to be clear enough that your reader can generalize and relate. Consider the essay “Comatose Dreams” in the previous section: it does exceptional work with implication, but some readers have trouble knowing what they should take away from the story to apply to their own lives.

It is also possible, though, to be too explicit. Take, for example, Charles Perrault’s 1697 publication of a classic folk story, “Little Red Riding Hood.”5 As with many fairy tales, this story is overtly didactic, stating the following moral after Little Red Riding Hood’s demise:

Moral: Children, especially attractive, well bred young ladies, should never talk to strangers, for if they should do so, they may well provide dinner for a wolf. I say “wolf,” but there are various kinds of wolves. There are also those who are charming, quiet, polite, unassuming, complacent, and sweet, who pursue young women at home and in the streets. And unfortunately, it is these gentle wolves who are the most dangerous ones of all.6

I encourage you to discuss the misogynist leanings of this moral with your class. For our purposes here, though, let’s consider what Perrault’s “wrap-up” does, rhetorically. With a target audience of, presumably, children, Perrault assumes that the moral needs to be spelled out. This paragraph does the “heavy lifting” of interpreting the story as an allegory; it explains what the reader is supposed to take away from the fairy tale so they don’t have to figure it out on their own. On the other side of that coin, though, it limits interpretive possibilities. Perrault makes the intent of the story unambiguous, making it less likely that readers can synthesize their own meaning.

Activities

What My Childhood Tastes Like7

To practice reflection, try this activity writing about something very important—food.

First, spend five minutes making a list of every food or drink you remember from childhood. Mine looks like this:

– Plain cheese quesadillas, made by my mom in the miniscule kitchenette of our one-bedroom apartment

– “Chicken”-flavored ramen noodles, at home alone after school

– Cayenne pepper cherry Jell-O at my grandparents’ house

– Wheat toast slathered in peanut butter before school

– Lime and orange freezy-pops

– My stepdad’s meatloaf—ironically, the only meatloaf I’ve ever liked

– Cookie Crisp cereal (“It’s cookies—for breakfast!”)

– Macintosh apples and creamy Skippy peanut butter

– Tostitos Hint of Lime chips and salsa

– Love Apple Stew that only my grandma can make right

– Caramel brownies, by my grandma who can’t bake anymore

Then, identify one of those foods that holds a special place in your memory. Spend another five minutes free-writing about the memories you have surrounding that food. What makes it so special? What relationships are represented by that food? What life circumstances? What does it represent about you? Here’s my model; I started out with my first list item, but then digressed—you too should feel free to let your reflective writing guide you.

My mom became a gourmet with only the most basic ingredients. We lived bare bones in a one-bedroom apartment in the outskirts of Denver; for whatever selfless reason, she gave four-year-old the bedroom and she took a futon in the living room. She would cook for me after caring for other mothers’ four-year-olds all day long: usually plain cheese quesadillas (never any sort of add-ons, meats, or veggies—besides my abundant use of store-brand ketchup) or scrambled eggs (again, with puddles of ketchup).

When I was 6, my dad eventually used ketchup as a rationale for my second stepmom: “Shane, look! Judy likes ketchup on her eggs too!” But it was my mom I remembered cooking for me every night—not Judy, and certainly not my father.

“I don’t like that anymore. I like barbecue sauce on my eggs.”

Reflection as a Rhetorical Gesture

Although reflection isn’t necessarily its own rhetorical mode, it certainly is a posture that you can apply to any mode of writing. I picture it as a pivot, perhaps off to the left somewhere, that opens up the diegetic gap and allows me to think through the impact of an experience. As mentioned earlier, this gesture can be represented by the phrase “When I look back now, I realize that…” To practice this pivot, try this exercise.

- Over five minutes, write a description of the person who taught you to tie your shoes, ride a bike, or some other life skill. You may tell the story of learning this skill if you want, but it is not necessary. (See characterization for more on describing people.)

- Write the phrase “When I look back now, I realize that.”

- Complete the sentence and proceed with reflective writing for another five minutes. What does your reflection reveal about that person that the narrative doesn’t showcase? Why? How might you integrate this “wrap-up” into a “weave”?

End-of-Episode Voice-Overs: Reflection in Television Shows

In addition to written rhetoric, reflection is also a tool used to provide closure in many television shows: writers use voiceovers in these shows in an attempt to neatly tie up separate narrative threads for the audience, or to provide reflective insight on what the audience just watched for added gravity or relevance for their lives. Often a show will use a voiceover toward the end of the episode to provide (or try to provide) a satisfying dénouement.

To unpack this trope, watch an episode of one of the following TV shows (available on Netflix or Hulu at the time of this writing) and write a paragraph in response to the questions below:

-

- Scrubs8

- Grey’s Anatomy

- The Wonder Years

- How I Met Your Mother

- Ally McBeal

- Jane the Virgin

- Sex and the City

- What individual stories were told in the episode? How was each story related to the others?

- Is there a common lesson at all the characters learned?

- At what point(s) does the voiceover use the gesture of reflection? Does it seem genuine? Forced? Satisfying? Frustrating?

Dr. Cox: “Grey’s Anatomy always wraps up every episode with some cheesy voice-over that ties together all of the storylines, which, incidentally, is my least favorite device on television.”

Elliot: “I happen to like the voice-overs on Grey’s Anatomy, except for when they’re really vague and generic.”

Voice-over (J.D.): And so, in the end, I knew what Elliot said about the way things were has forever changed the way we all thought about them. – Scrubs

Model Texts by Student Authors

Slowing Down9

I remember a time when I was still oblivious to it. My brother, sister, and I would pile out of the car and race through the parking lot to the store, or up the driveway to the house, never so much as a glance backward. I’m not sure exactly when it happened, but at some point I started to take notice, fall back, slow my pace, wait for him.

My dad wasn’t always that slow. He didn’t always have to concentrate so hard to just put one foot in front of the other. Memory has a way of playing tricks on you, but I swear that I can remember him being tall, capable, and strong once. When I was real little he could put me on his shoulders and march me around: I have pictures to prove it. I also have fuzzy memories of family camping trips—him taking us to places like Yosemite, Death Valley, and the California coast. What I remember clearly, though, was him driving to and from work every day in that old flatbed truck with the arc welder strapped to the back, going to fix boilers, whatever those were.

My dad owned his own business; I was always proud of that. I’d tell my friends that he was the boss. Of course, he was the sole employee, aside from my mom who did the books. I didn’t tell them that part. But he did eventually hire a guy named David. My mom said it was to “be his hands.” At the time I wasn’t sure what that meant but I knew that his hands certainly looked different than other people’s, all knotty. And he’d started to use that foam thing that he’d slip over his fork or toothbrush so he could grip it better. I supposed that maybe a new set of hands wasn’t a bad idea.

When I was about 8, he and my mom made a couple of trips to San Francisco to see a special doctor. They said that he’d need several surgeries before they were through, but that they’d start on his knees. I pictured my dad as a robot, all of his joints fused together with nuts and bolts. I wondered if I’d have to oil him, like the tin man. It made me laugh to think about it: bionic dad. That wouldn’t be so bad; maybe I could take him to show and tell. To be honest, I was sometimes a little embarrassed by the way he looked when he came to pick me up at school or my friend’s house. He wore braces in his boots to help him walk, he always moved so slow, and his hands had all those knots that made them curl up like old grapevines. And then there was that dirty old fanny pack he always carried with him because he couldn’t reach his wallet if it was in his pocket. Yeah, bionic dad would be an improvement.

It was around this time that my parents decided to give up the business. That was fine with me; it meant he’d be home all day. Also, his flatbed work truck quickly became our new jungle gym and the stage for many new imaginary games. Maybe it was him not being able to work anymore that finally made it click for me, but I think it was around this time that I started to slow down a bit, wait for him.

He could still drive—he just needed help starting the ignition. But now, once we’d get to where we were going, I’d try not to walk too fast. It had begun to occur to me that maybe walking ahead of him was kind of disrespectful or insensitive. In a way, I think that I just didn’t want him to know that my legs worked better than his. So, I’d help him out of the car, offer to carry his fanny pack, and try to walk casually next to him, as if I’d always kept that pace.

I got pretty good at doing other stuff for him, too; we all did. He couldn’t really reach above shoulder height anymore, so aside from just procuring cereal boxes from high shelves we’d take turns combing his hair, helping him shave, or changing his shirt. I never minded helping out. I had spent so many years being my dad’s shadow and copying him in every aspect that I possibly could; helping him out like this just made me feel useful, like I was finally a worthy sidekick. I pictured Robin combing Batman’s hair. That probably happened from time to time, right?

Once I got to high school, our relationship began to change a bit. I still helped him out, but we had started to grow apart. I now held my own opinions about things, and like most kids in the throes of rebellion, I felt the need to make this known at every chance I got. I rejected his music, politics, TV shows, sports, you name it. Instead of being his shadow we became more like reflections in a mirror; we looked the same, but everything was opposite, and I wasted no opportunity to demonstrate this.

We argued constantly. Once in particular, while fighting about something to do with me not respecting his authority, he came at me with his arms crossed in front of him and shoved me. I was taller than him by this point, and his push felt akin to someone not paying attention and accidentally bumping into me while wandering the aisles at the supermarket. It was nothing. But it was also the first time he’d ever done anything like that, and I was incredulous—eager, even—at the invitation to assert myself physically. I shoved him back. He lost his footing and flailed backwards. If the refrigerator hadn’t been there to catch him he would have fallen. I still remember the wild look in his eyes as he stared at me in disbelief. I felt ashamed of myself, truly ashamed, maybe for the first time ever. I offered no apology, though, just retreated to my room.

In those years, with all the arguing, I just thought of my dad as having an angry heart. It seemed that he wasn’t just mad at me: he was mad at the world. But to his credit, as he continued to shrink, as his joints became more fused and his extremities more gnarled, he never complained, and never stopped trying to contribute. And no matter how much of an entitled teenaged brat I was, he never stopped being there when I needed him, so I tried my best to return the favor.

It wasn’t until I moved out of my parents’ house that I was able to really reflect on my dad’s lot in life. His body had started to betray him in his mid-20s and continued to work against him for the rest of his life. He was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, the worst case that his specialists had seen, and eventually had surgery on both knees, ankles, wrists, elbows, and shoulders. Not that they helped much. He had an Easter-sized basket full of pills he had to take every day. When I was younger I had naively thought that those pills were supposed to help him get better. But now that I was older I finally realized that their only purpose was to mitigate pain. I decided that if I were him, I’d be pretty pissed off too.

I was 24 and living in Portland the morning that I got the call. I was wrong about his heart being angry. Turned out it was just weak. With all of those pills he took, I should have known that it was only a matter of time before it would give out; I’m pretty sure he did.

When I think back on it, my dad had a lot of reasons to be angry. Aside from he himself being shortchanged, he had us to consider. I know it weighed on him that he couldn’t do normal “dad” stuff with us. And then there was my mom. Their story had started out so wild and perfect, a couple of beautiful longhaired kids that met and fell in love while hitchhiking in Canada. She had moved across the country to marry him. The unfairness that life didn’t go as they’d planned, that she’d be a young widow—these are things I know he thought about. But he never mentioned them. He never complained. He never talked about the pain he was in, even though I know now it was constant. I guess at some point he became like the fish that doesn’t know it’s in water. That, or he just made his peace with it somehow.

It took me a long time to find my own peace in his situation. Our situation. I was angry for myself and my family, but mostly I was angry for him. I was pissed that he had to spend the last twenty something years of his life in that prison he called a body. Eventually though, that anger gave way to other feelings. Gratitude, mostly. I don’t think that my dad could have lived a hundred healthy years and taught me the same lessons that I learned from watching him suffer. He taught me about personal sacrifice, the brevity of life, how it can be both a blessing and a curse. All kids are egocentric (I know I definitely was), but he was the first one to make me think outside of myself, without having to ask me to do it. He taught me what compassion and patience looked like. He taught me to slow down.

Teacher Takeaways

“This essay is commendable for its deft narration — replete with a balanced use of specific descriptions and general exposition. However, the mixture of simple past tense with simple future tense (used here to indicate the future in the past) situates both the reader and the narrator primarily in the past. This means that we really don’t get to the simple present tense (i.e. across the diegetic gap) until the final two paragraphs of the essay. That said, the narrator’s past reflections are integrated often throughout the essay, making it more an example of ‘weaving’ than of ‘wrap-up.’”– Professor Fiscaletti

Untitled10

The sky was white, a blank canvas, when I became the middle school’s biggest and most feared bully. The sky was white and my hands were stained red with blood—specifically a boy named Garrett’s blood. I was 12 years old, smaller than average with clothes-hanger collar bones but on that day I was the heavyweight champion. It wasn’t as if I’d just snapped out of the blue; it wasn’t as if he were innocent. He had just been the only one within arms-length at the time when my heart beat so loudly in my ears, a rhythm I matched with my fists. I was dragged off of him minutes later by stunned teachers (who had never seen me out of line before) and escorted to the Principal’s Office. They murmured over my head as if I couldn’t hear them. “What do you think that was about?” “Who started it?” I was tightlipped and frightened, shaking and wringing my hands, rusting with someone else’s blood on them. Who started it? That particular brawl could have arguably been started by me: I jumped at him, I threw the only punches. But words are what started the fight. Words were at the root of my anger.

I was the kid who was considered stupid: math, a foreign language my tongue refused to speak. I was pulled up to the front of the classroom by my teachers who thought struggling my way through word problems on the whiteboard would help me

grasp the concepts, but all I could ever do was stand there humiliated, red-faced with clenched fists until I was walked through the equation, step by step. I was the one who tripped over my words when I had to read aloud in English, the sentences rearranging themselves on the page until tears blurred my vision. I never spoke in class because I was nervous—“socially anxious” is what the doctors called it. Severe social anxiety with panic disorder. I sat in the back and read. I sat at lunch and read because books were easier to talk to than people my own age. Kids tease; it’s a fact of life. But sometimes kids are downright cruel. They are relentless. When they find an insecurity, they will poke and prod it, an emotional bruise. A scar on my heart. Names like “idiot” and “loser” and “moron” are phrases chanted like a prayer at me in the halls, on the field, in the lunchroom. They are casual bombs tossed at me on the bus and they detonate around my feet, kicking up gravel and stinging my eyes. What is the saying? Sticks and stones will break my bones but words will never hurt me? Whoever came up with that has quite obviously never been a 12-year-old girl.

The principal stared at me as I walked in, his eyes as still as water. He told me my parents had to be called, I had to be suspended the rest of the week, this is a no-tolerance school. Many facts were rattled off. I began to do what I do best—tune him out—when he said something that glowed. It caught my attention, held my focus. “Would you like to tell me your side of the story?” I must have looked shocked because he half-smiled when he said, “I know there are always two sides. I know you wouldn’t just start a fist fight out of nowhere. Did he do something to you?” An avalanche in my throat, the words came crashing out. I explained the bullying, how torturous it was for me to wake up every morning and know I would have to face the jeers and mean comments all day. I told him about how when I put on my uniform every morning, it felt like I was gearing up for a battle I didn’t sign up for and knew I

wouldn’t win. The shame and embarrassment I wore around me like a shawl slipped off. He listened thoughtfully, occasionally pressing his fingers together and bringing them to his pursed lips, his still eyes beginning to ripple, a silent storm. When I was done he apologized. How strange and satisfying to be apologized to by a grown-up. I was validated with that simple “I’m sorry.” I almost collapsed on the floor in gratitude. My parents entered the room, worry and anger etched on their faces, folded up in the wrinkles that were just then starting to line their skin. My parents listened as I retold my story, admitted what I had been bottling up for months. I was relieved, I felt the cliché weight lifted off of my too-narrow shoulders. My principal assured my parents that this was also a no-tolerance stance on bullying and he was gravely sorry the staff hadn’t known about the abuse earlier. I was still suspended for three days, but he said to make sure I didn’t miss Monday’s assembly. He thought it would be important for me.

The Monday I returned, there was an assembly all day. I didn’t know what it was for, but I knew everyone had to be there on time so I hurried to find a seat. People avoided eye-contact with me. As I pushed past them, I could feel the whispers like taps on my shoulder. I sat down and the assembly began. It was a teenage girl and she was talking about differences, about how bullying can affect people more than you could ever know. I was leaning forward in my seat trying to hang onto every word because she was describing how I had felt every day for months. She spoke about how her own anxiety and learning disability isolated her. She was made fun of and bullied and she became depressed. It was important to her for us to hear her story because she wanted people like her, like me, to know they weren’t alone and that words can do the most damage of all. R.A.D. Respect all differences, a movement that was being implemented in the school to accept and celebrate everybody. At the end of her

speech, she asked everyone who had ever felt bullied or mistreated by their peers to stand up. Almost half of the school stood, and I felt like a part of my school for the first time. She then invited anyone who wanted to speak to come up and take the mic. To my surprise, there were multiple volunteers. A line formed and I found myself in it.

I heard kids I’d never talked to before speak about their ADHD, their dyslexia, how racist comments can hurt. I had no idea so many of my classmates had been verbal punching bags; I had felt utterly alone. When it was my turn I explained what it means to be socially anxious. How in classrooms and crowds in general I felt like I was being suffocated: it was hard to focus because I often forgot to breathe. How every sentence I ever spoke was rehearsed at least 15 times before I said it aloud: it was exhausting. I was physically and emotionally drained after interactions, like I had run a marathon. I didn’t like people to stare at me because I assumed everyone disliked me, and the bullying just solidified that feeling of worthlessness. It was exhilarating and terrifying to have everyone’s eyes on me, everyone listening to what it was like to be inside my head. I stepped back from the microphone and expected boos, or maybe silence. But instead everyone clapped, a couple teachers even stood up. I was shocked but elated. Finally I was able to express what I went through on a day-to-day basis.

The girl who spoke came up to me after and thanked me for being brave. I had never felt brave in my life until that moment. And yes, there was the honeymoon period. Everyone in the school was nice to each other for about two weeks before everything returned to normal. But for me it was a new normal: no one threw things at me in the halls, no one called me names, my teachers were respectful of my anxiety by not singling me out in class. School should be a sanctuary, a safe space where students feel free to be exactly who they are, free of ridicule or judgment. School had never been that for me, school had been a warzone littered with minefields. I dreaded facing my school days, but then I began to look forward to them. I didn’t have to worry about being made fun of anymore. From that moment on, it was just school. Not a place to be feared, but a place to learn.

Teacher Takeaways

“This author obviously has a knack for descriptive metaphor and simile, and for the sonic drive of repetition, all of which contribute to the emotional appeal of the narrative. The more vivid the imagery, the more accessible the event. However, the detailed narrative is only briefly interrupted by the author’s current ideas or interpretations; she might consider changing the structure of the essay from linear recollection to a mix of narrative and commentary from herself, in the present. Still, the essay does serve as an example of implicit reflection; the author doesn’t do much of the ‘heavy lifting’ for us.”– Professor Fiscaletti

Parental Guidance11

“Derek, it’s Dad!” I already knew who it was because the call was made collect from the county jail. His voice sounded clean: he didn’t sound like he was fucked up. I heard from his ex-girlfriend about a year earlier that he was going to jail for breaking into her apartment and hiding under her bed with a knife then popping out and threatening her life; probably other stuff too. I wasn’t all that surprised to hear from him. I was expecting a call eventually. I was happy to hear from him. I missed him. He needed a place to stay for a couple weeks. I wanted to be a good son. I wanted him to be proud of me. My room-mates said it was alright. I gave him the address to our apartment and told him to come over. I was 19.

I am told when I was a toddler I wouldn’t let my dad take the garbage outside without me hitching a ride on his boot. I would straddle his foot like a horse and hang onto his leg; even in the pouring rain. He was strong, funny and a good surfer. One time at the skatepark when I was 6 or 7 he made these guys leave for smoking pot in front of me and my little sister. He told them to get that shit out of here and they listened. He was protecting us. I wanted to be just like him.

When my dad got to the apartment he was still wearing his yellow jail slippers. They were rubber with a single strap. No socks, a t-shirt and jeans was all he had on. It was January: cold and rainy. He was clean and sober from what I could tell by his voice and eyes. He was there. I hugged him. I was hopeful that maybe he was back for good. I found my dad a pair of warm socks and a hoodie. We were drinking beer and one of my friends offered him one. He must have wanted one but he knows where that leads and he said no thanks. We all got stoned instead.

One time when I was in 7th grade my dad was driving me and my siblings home from school. He saw someone walking down the street wearing a nice snowboarding jacket. It looked just like my dad’s snowboarding jacket which he claimed was stolen from the van while he was at work. He pulled the van over next to this guy and got out. He began threatening him. He was cursing and yelling and throwing his hands up and around. I was scared.

He said he only needed a couple weeks to get back on his feet. I was happy to have him there. As long as he wasn’t drinking or using drugs he had a chance. He said he was done with all that other shit. He just needs to smoke some pot to relax at night and he will be fine. Sounded reasonable to me. It had been about a year since I dropped out of high school and moved out of my mom’s. I worked full time making pizza and smoked pot and drank beer with my friends and roommates. Occasionally there was some coke or ecstasy around but mostly just beer, pot and video games.

One day in 4th grade when we were living in Coos Bay the whole family went to the beach to surf and hang out. My mom and dad were together and it seemed like they loved each other. My littlest sister was a toddler and ran around on the beach in the sun with my mom and our Rottweiler Lani. My older brother and other sister were in the ocean with me and my dad. We all took turns being pushed into waves on our surfboards by dad. We all caught waves and had a great day. My mom cheered us on from the shore. He was a good dad.

Two weeks passed quickly and my dad was still staying at our apartment. One day while I was at work my dad blew some coke with my roommate. I could tell something was off when I got home. I was worried. He said he was leaving for a couple days to go stay with his friend who is a pastor. He needed some spiritual guidance or something like that. He sounded fucked up.

Growing up we did a lot of board sports. My dad owned a surf shop in Lincoln City for a while and worked as a sales representative for various gear companies. We had surfboards, snowboards, windsurfers, sails, wakeboards, wetsuits: several thousand dollars’ worth of gear. One day my dad told us someone broke into our garage and stole all the gear. The window in the garage was broken except it appeared to be broken from the inside. He didn’t file a police report. My middle school surf club coach tried to get my surfboard from the pawnshop but it was too expensive and the pawn shop owner wouldn’t give it back. I felt betrayed.

I came home from work and found my dad in my room passed out. I stumbled over an empty beer can on the way in and there were cheap whiskey bottles scattered about. It smelled horrible. He woke up and was ashamed. He looked up at me from my bed with a thousand pounds pulling down on his puffy eyelids and asked me for a cigarette. He was strung out. Half of our spoons went missing. It smelled like booze, heroin and filth. I was ashamed.

One day in 9th grade I came home from school to find my brother lifting blood stains out of the carpet with hydrogen peroxide. He said some guys came over and beat dad up. He owed them money or stole from them or something. I wanted to call my mom. I was scared.

I told my dad he had to leave. He pleaded to stay for another thirty minutes. I would be at work by then. While I was at work my friends escorted him out. He said he was going to his friend the pastor’s house. I didn’t hear from him for a couple years after that.

We learn a lot from our parents. Sometimes the best lessons are those on what not to do.

My two-year-old daughter calls me Papa, Daddy, Dad or Derek. Whatever she calls me it has a positive meaning. When we are driving she says from her car-seat, “Daddy’s hand”, “I want daddy’s hand please” and I reach back and put it on her lap.

One day my daughter woke me up and said, “Oh hi Daddy! I wanna go forest. I wanna go hike!” She was smiling. We practiced the alphabet before breakfast then went for a walk in the woods: mama, papa and baby. I’m a good dad.

Teacher Takeaways

“One of the most notable features of this essay is the timeline: by jumping back and forth in chronology between parallel but distinct experiences, the author opens up the diegetic gap and demonstrates a profound impact through simple narration. I also like this author’s use of repetition and parallel structure. However, the author’s description could take a cue from ‘Comatose Dreams’ to develop more complex, surprising descriptors. While the essay makes use of sensory language, I want more dramatic or unanticipated imagery.”– Professor Dawson

Endnotes

a rhetorical gesture by which an author looks back, through the diegetic gap, to demonstrate knowledge or understanding gained from the subject on which they are reflecting. May also include consideration of the impact of that past subject on the author’s future—“Looking back in order to look forward.”

from “diegesis,” the temporal distance between a first-person narrator narrating and the same person acting in the plot events. I.e., the space between author-as-author and author-as-character.