Chapter One: Describing a Scene or Experience

This morning, as I was brewing my coffee before rushing to work, I found myself hurrying up the stairs back to the bedroom, a sense of urgency in my step. I opened the door and froze—what was I doing? Did I need something from up here? I stood in confusion, trying to retrace the mental processes that had led me here, but it was all muddy.

It’s quite likely that you’ve experienced a similarly befuddling situation. This phenomenon can loosely be referred to as automatization: because we are so constantly surrounded by stimuli, our brains often go on autopilot. (We often miss even the most explicit stimuli if we are distracted, as demonstrated by the Invisible Gorilla study.)

Automatization is an incredibly useful skill—we don’t have the time or capacity to take in everything at once, let alone think our own thoughts simultaneously—but it’s also troublesome. In the same way that we might run through a morning ritual absent-mindedly, like I did above, we have also been programmed to overlook tiny but striking details: the slight gradation in color of cement on the bus stop curb; the hum of the air conditioner or fluorescent lights; the weight and texture of a pen in the crook of the hand. These details, though, make experiences, people, and places unique. By focusing on the particular, we can interrupt automatization.1 We can become radical noticers by practicing good description.

In a great variety of rhetorical situations, description is an essential rhetorical mode. Our minds latch onto detail and specificity, so effective description can help us experience a story, understand an analysis, and nuance a critical argument. Each of these situations requires a different kind of description; this chapter focuses on the vivid, image-driven descriptive language that you would use for storytelling.

Chapter Vocabulary

|

Vocabulary |

Definition |

|

a writing technique by which an author tries to follow a rule or set of rules in order to create more experimental or surprising content, popularized by the Oulipo school of writers. |

|

|

a rhetorical mode that emphasizes eye-catching, specific, and vivid portrayal of a subject. Often integrates imagery and thick description to this end. |

|

|

a method of reading, writing, and thinking that emphasizes the interruption of automatization. Established as “остранение” (“estrangement”) by Viktor Shklovsky, defamiliarization attempts to turn the everyday into the strange, eye-catching, or dramatic. |

|

|

a study of a particular culture, subculture, or group of people. Uses thick description to explore a place and its associated culture. |

|

|

language which implies a meaning that is not to be taken literally. Common examples include metaphor, simile, personification, onomatopoeia, and hyperbole. |

|

|

sensory language; literal or figurative language that appeals to an audience’s imagined sense of sight, sound, smell, touch, or taste. |

|

|

economical and deliberate language which attempts to capture complex subjects (like cultures, people, or environments) in written or spoken language. Coined by anthropologists Clifford Geertz and Gilbert Ryle. |

|

Techniques

Imagery and Experiential Language

Strong description helps a reader experience what you’ve experienced, whether it was an event, an interaction, or simply a place. Even though you could never capture it perfectly, you should try to approximate sensations, feelings, and details as closely as you can. Your most vivid description will be that which gives your reader a way to imagine being themselves as of your story.

Imagery is a device that you have likely encountered in your studies before: it refers to language used to ‘paint a scene’ for the reader, directing their attention to striking details. Here are a few examples:

- Bamboo walls, dwarf banana trees, silk lanterns, and a hand-size jade Buddha on a wooden table decorate the restaurant. For a moment, I imagined I was on vacation. The bright orange lantern over my table was the blazing hot sun and the cool air currents coming from the ceiling fan caused the leaves of the banana trees to brush against one another in soothing crackling sounds.2

- The sunny midday sky calls to us all like a guilty pleasure while the warning winds of winter tug our scarves warmer around our necks; the City of Roses is painted the color of red dusk, and the setting sun casts her longing rays over the Eastern shoulders of Mt. Hood, drawing the curtains on another crimson-grey day.3

- Flipping the switch, the lights flicker—not menacingly, but rather in a homey, imperfect manner. Hundreds of seats are sprawled out in front of a black, worn down stage. Each seat has its own unique creak, creating a symphony of groans whenever an audience takes their seats. The walls are adorned with a brown mustard yellow, and the black paint on the stage is fading and chipped.4

You might notice, too, that the above examples appeal to many different senses. Beyond just visual detail, good imagery can be considered sensory language: words that help me see, but also words that help me taste, touch, smell, and hear the story. Go back and identify a word, phrase, or sentence that suggests one of these non-visual sensations; what about this line is so striking?

Imagery might also apply figurative language to describe more creatively. Devices like metaphor, simile, and personification, or hyperbole can enhance description by pushing beyond literal meanings.

Using imagery, you can better communicate specific sensations to put the reader in your shoes. To the best of your ability, avoid clichés (stock phrases that are easy to ignore) and focus on the particular (what makes a place, person, event, or object unique). To practice creating imagery, try the Imagery Inventory exercise and the Image Builder graphic organizer in the Activities section of this chapter.

Thick Description

If you’re focusing on specific, detailed imagery and experiential language, you might begin to feel wordy: simply piling up descriptive phrases and sentences isn’t always the best option. Instead, your goal as a descriptive writer is to make the language work hard. Thick description refers to economy of language in vivid description. While good description has a variety of characteristics, one of its defining features is that every word is on purpose, and this credo is exemplified by thick description.

Thick description as a concept finds its roots in anthropology, where ethnographers seek to portray deeper context of a studied culture than simply surface appearance.5 In the world of writing, thick description means careful and detailed portrayal of context, emotions, and actions. It relies on specificity to engage the reader. Consider the difference between these two descriptions:

The market is busy. There is a lot of different produce. It is colorful.

vs.

Customers blur between stalls of bright green bok choy, gnarled carrots, and fiery Thai peppers. Stopping only to inspect the occasional citrus, everyone is busy, focused, industrious.

Notice that, even though the second description is longer, its major difference is the specificity of its word choice. The author names particular produce, which brings to mind a sharper image of the selection, and uses specific adjectives. Further, though, the words themselves do heavy lifting—the nouns and verbs are descriptive

too! “Customers blur” both implies a market (where we would expect to find “customers”) and also illustrates how busy the market is (“blur” implies speed), rather than just naming it as such.

Consider the following examples of thick description:

I had some strength left to wrench my shoulders and neck upward but the rest of my body would not follow. My back was twisted like a contortionist’s.6

Shaking off the idiotic urge to knock, I turned the brass knob in my trembling hands and heaved open the thick door. The hallway was so dark that I had to squint while clumsily reaching out to feel my surroundings so I wouldn’t crash into anything.7

Snow-covered mountains, enormous glaciers, frozen caves and massive caps of ice clash with heat, smoke, lava and ash. Fields dense with lush greenery and vibrant purple lupine plants butt up against black, barren lands scorched by eruptions. The spectacular drama of cascading waterfalls, rolling hills, deep canyons and towering jagged peaks competes with open expanses of flat, desert-like terrain.8

Where do you see the student authors using deliberate, specific, and imagistic words and phrases? Where do you see the language working hard?

Unanticipated and Eye-catching Language

In addition to our language being deliberate, we should also strive for language that is unanticipated. You should control your language, but also allow for surprises—for you and your reader! Doing so will help you maintain attention and interest from your reader because your writing will be unique and eye-catching, but it also has benefits for you: it will also make your writing experience more enjoyable and educational.

How can you be surprised by your own writing, though? If you’re the author, how could you not know what you’re about to say? To that very valid question, I have two responses:

On a conceptual level: Depending on your background, you may currently consider drafting to be thinking-then-writing. Instead, you should try thinking-through-writing: rather than two separate and sequential acts, embrace the possibility that the act of writing can be a new way to process through ideas. You must give yourself license to write before an idea is fully formed—but remember, you will revise, so it’s okay to not be perfect. (I highly recommend Anne Lamott’s “Shitty First Drafts.”)

On a technical level: Try out different activities—or even invent your own—that challenge your instincts. Rules and games can help you push beyond your auto-pilot descriptions to much more eye-catching language!

Constraint-based writing is one technique like this. It refers to a process which requires you to deliberately work within a specific set of writing rules, and it can often spark unexpected combinations of words and ideas. The most valuable benefit to constraint-based writing, though, is that it gives you many options for your descriptions: because first idea ≠ best idea, constraint-based writing can help you push beyond instinctive descriptors.

When you spend more time thinking creatively, the ordinary can become extraordinary. The act of writing invites discovery! When you challenge yourself to see something in new ways, you actually see more of it. Try the Dwayne Johnson activity to think more about surprising language.Activities

Specificity Taxonomy

Good description lives and dies in particularities. It takes deliberate effort to refine our general ideas and memories into more focused, specific language that the reader can identify with.

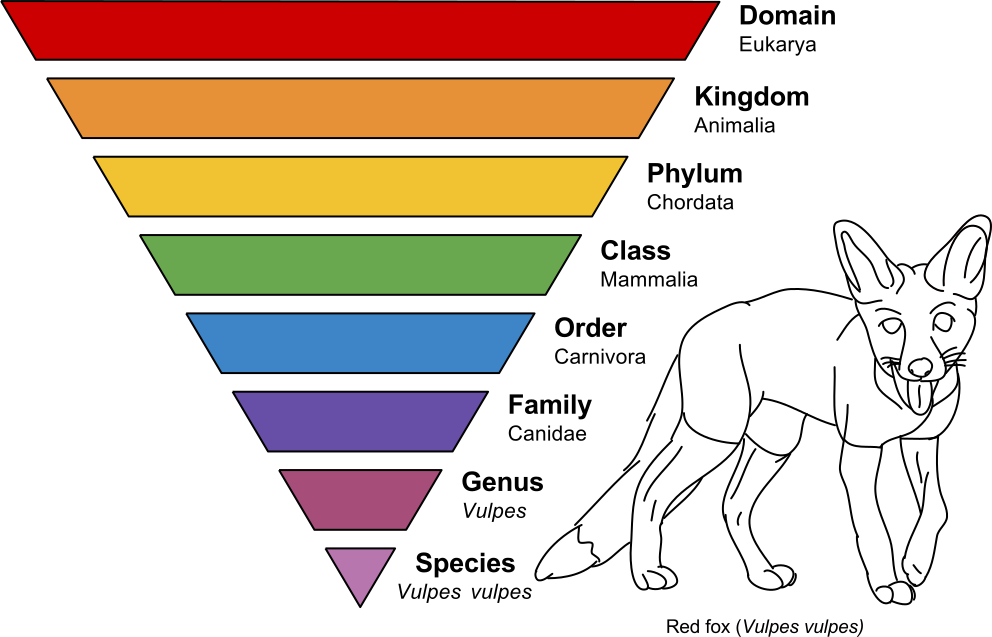

A taxonomy is a system of classification that arranges a variety of items into an order that makes sense to someone. You might remember from your biology class the ranking taxonomy based on Carl Linnaeus’ classifications, pictured here.

To practice shifting from general to specific, fill in the blanks in the taxonomy9 below. After you have filled in the blanks, use the bottom three rows to make your own. As you work, notice how attention to detail, even on the scale of an individual word, builds a more tangible image.

|

|

More General |

General |

Specific |

More Specific |

|

(example): |

animal |

mammal |

dog |

Great Dane |

|

1a |

organism |

|

conifer |

Douglas fir |

|

1b |

|

airplane |

|

Boeing 757 |

|

2a |

|

novel |

|

Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire |

|

2b |

clothing |

|

blue jeans |

|

|

3a |

medical condition |

|

respiratory infection |

the common cold |

|

3b |

school |

college |

|

|

|

4a |

artist |

|

pop singer |

|

|

4b |

structure |

building |

|

The White House |

|

5a |

|

coffee |

Starbucks coffee |

|

|

5b |

|

scientist |

|

Sir Isaac Newton |

|

6a |

|

|

|

|

|

6b |

|

|

|

|

|

6c |

|

|

|

|

Compare your answers with a classmate. What similarities do you share with other students? What differences? Why do you think this is the case? How can you apply this thinking to your own writing?

Micro-Ethnography

An ethnography is a form of writing that uses thick description to explore a place and its associated culture. By attempting this method on a small scale, you can practice specific, focused description.

Find a place in which you can observe the people and setting without actively involving yourself. (Interesting spaces and cultures students have used before include a poetry slam, a local bar, a dog park, and a nursing home.) You can choose a place you’ve been before or a place you’ve never been: the point here is to look at a space and a group of people more critically for the sake of detail, whether or not you already know that context.

As an ethnographer, your goal is to take in details without influencing those details. In order to stay focused, go to this place alone and refrain from using your phone or doing anything besides note-taking. Keep your attention on the people and the place.

Spend a few minutes taking notes on your general impressions of the place at this time.

Use imagery and thick description to describe the place itself. What sorts of interactions do you observe? What sort of tone, affect, and language is used? How would you describe the overall atmosphere?

Spend a few minutes “zooming in” to identify artifacts—specific physical objects being used by the people you see.

Use imagery and thick description to describe the specific artifacts.

How do these parts contribute to/differentiate from/relate to the whole of the scene?

After observing, write one to two paragraphs synthesizing your observations to describe the space and culture. What do the details represent or reveal about the place and people?

Imagery Inventory

Visit a location you visit often—your classroom, your favorite café, the commuter train, etc. Isolate each of your senses and describe the sensations as thoroughly as possible. Take detailed notes in the organizer below, or use a voice-recording app on your phone to talk through each of your sensations.

|

Sense |

Sensation |

|

Sight |

|

|

Sound |

|

|

Smell |

|

|

Touch |

|

|

Taste |

|

Now, write a paragraph that synthesizes three or more of your sensory details. Which details were easiest to identify? Which make for the most striking descriptive language? Which will bring the most vivid sensations to your reader’s mind?

The Dwayne Johnson Activity

This exercise will encourage you to flex your creative descriptor muscles by generating unanticipated language.

Begin by finding a mundane object. (A plain, unspectacular rock is my go-to choice.) Divide a blank piece of paper into four quadrants. Set a timer for two minutes; in this time, write as many describing words as possible in the first quadrant. You may use a bulleted list. Full sentences are not required.

Now, cross out your first quadrant. In the second quadrant, take five minutes to write as many new describing words as possible without repeating anything from your first quadrant. If you’re struggling, try to use imagery and/or figurative language.

For the third quadrant, set the timer for two minutes. Write as many uses as possible for your object.

Before starting the fourth quadrant, cross out the uses you came up with for the previous step. Over the next five minutes, come up with as many new uses as you can.

After this generative process, identify your three favorite items from the sections you didn’t cross out. Spend ten minutes writing in any genre or form you like—a story, a poem, a song, a letter, anything—on any topic you like. Your writing doesn’t have to be about the object you chose, but try to incorporate your chosen descriptors or uses in some way.

Share your writing with a friend or peer, and debrief about the exercise. What surprises did this process yield? What does it teach us about innovative language use?10

1) Writing invites discovery: the more you look, the more you see.

2) Suspend judgment: first idea ≠ best idea.

3) Objects are not inherently boring: the ordinary can be dramatic if described creatively.

Surprising Yourself: Constraint-Based Scene Description

This exercise11 asks you to write a scene, following specific instructions, about a place of your choice. There is no such thing as a step-by-step guide to descriptive writing; instead, the detailed instructions that follow are challenges that will force you to think differently while you’re writing. The constraints of the directions may help you to discover new aspects of this topic since you are following the sentence-level prompts even as you develop your content.

- Bring your place to mind. Focus on “seeing” or “feeling” your place.

- For a title, choose an emotion or a color that represents this place to you.

- For a first line starter, choose one of the following and complete the sentence:

- You stand there…When I’m here, I know that…

- Every time…I [see/smell/hear/feel/taste]…

- We had been…I think sometimes…

- After your first sentence, create your scene, writing the sentences according to the following directions:

- Sentence 2: Write a sentence with a color in it.

- Sentence 3: Write a sentence with a part of the body in it.

- Sentence 4: Write a sentence with a simile (a comparison using like or as)

- Sentence 5: Write a sentence of over twenty-five words.

- Sentence 6: Write a sentence of under eight words.

- Sentence 7: Write a sentence with a piece of clothing in it.

- Sentence 8: Write a sentence with a wish in it.

- Sentence 9: Write a sentence with an animal in it.

- Sentence 10: Write a sentence in which three or more words alliterate; that is, they begin with the same initial consonant: “She has been left, lately, with less and less time to think….”

- Sentence 11: Write a sentence with two commas.

- Sentence 12: Write a sentence with a smell and a color in it.

- Sentence 13: Write a sentence without using the letter “e.”

- Sentence 14: Write a sentence with a simile.

- Sentence 15: Write a sentence that could carry an exclamation point (but don’t use the exclamation point).

- Sentence 16: Write a sentence to end this portrait that uses the word or words you chose for a title.

- Read over your scene and mark words/phrases that surprised you, especially those rich with possibilities (themes, ironies, etc.) that you could develop.

- On the right side of the page, for each word/passage you marked, interpret the symbols, name the themes that your description and detail suggest, note any significant meaning you see in your description.

- On a separate sheet of paper, rewrite the scene you have created as a more thorough and cohesive piece in whatever genre you desire. You may add sentences and transitional words/phrases to help the piece flow.

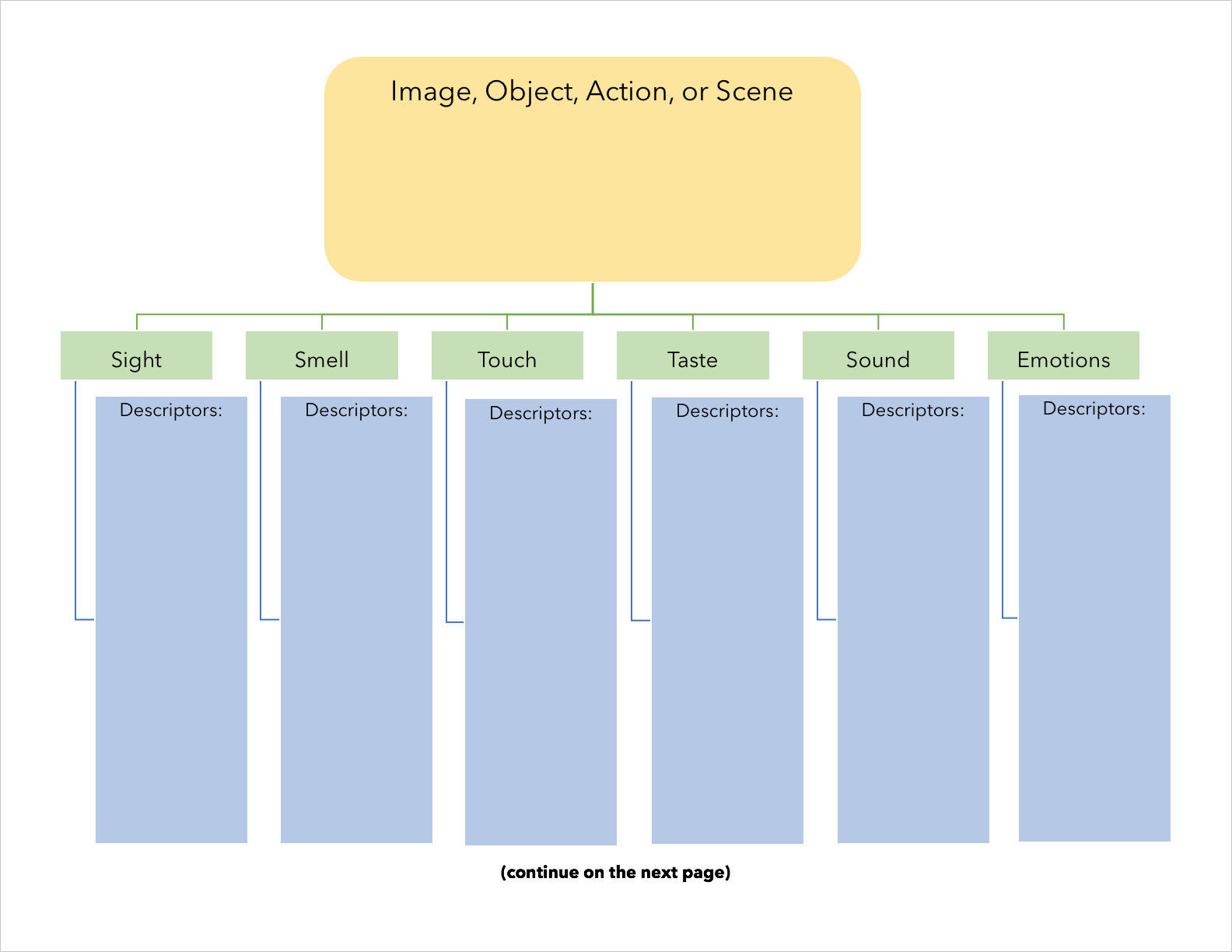

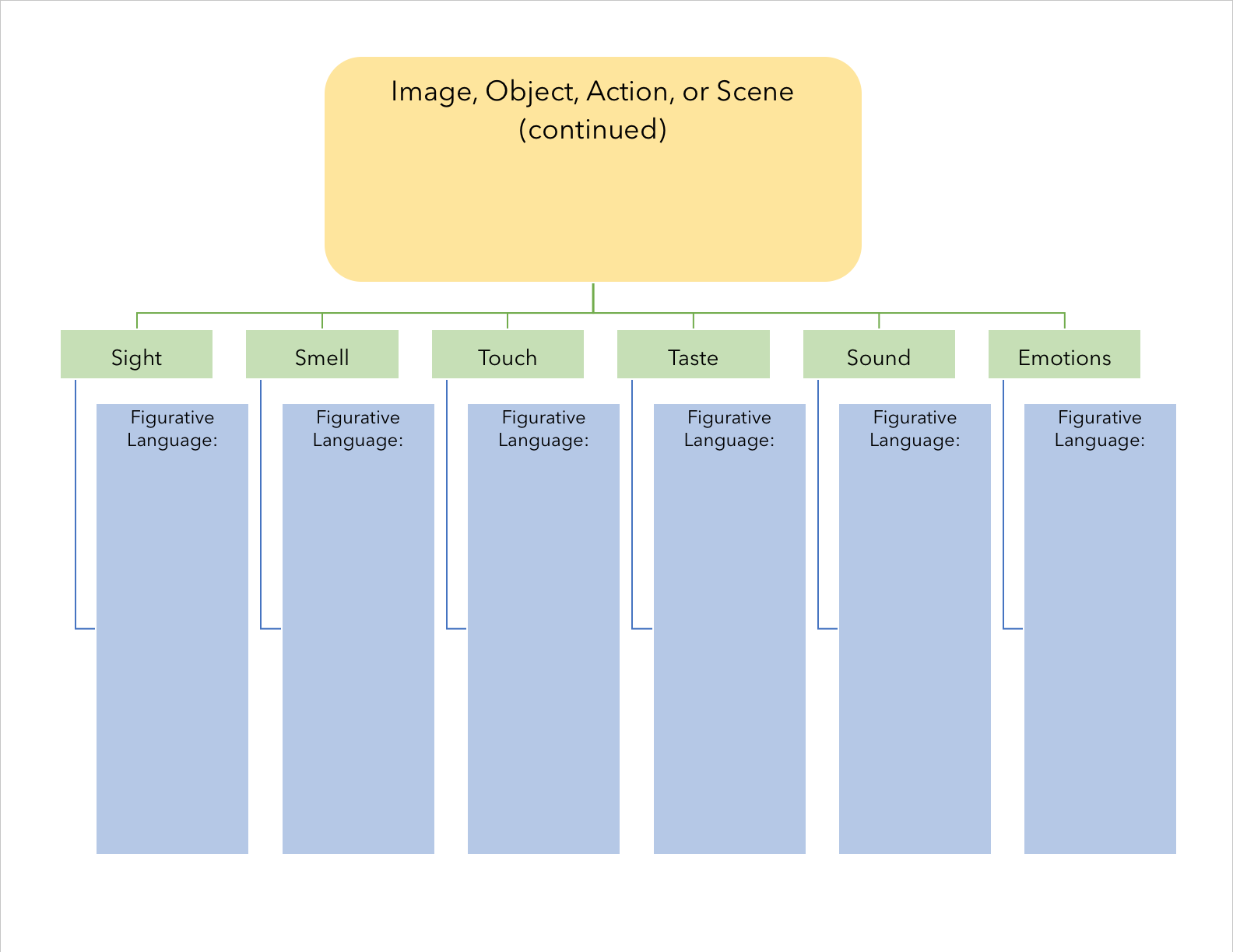

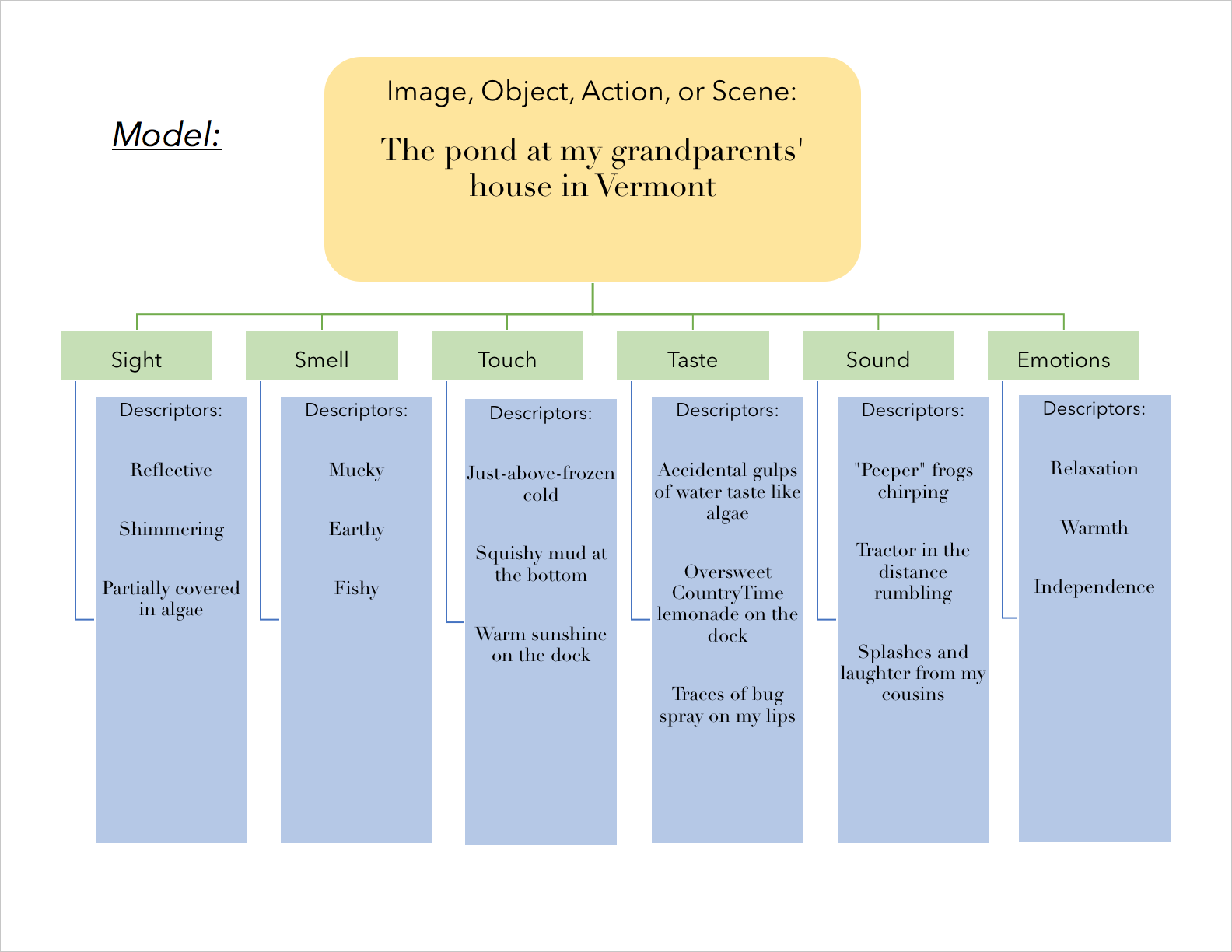

Image Builder

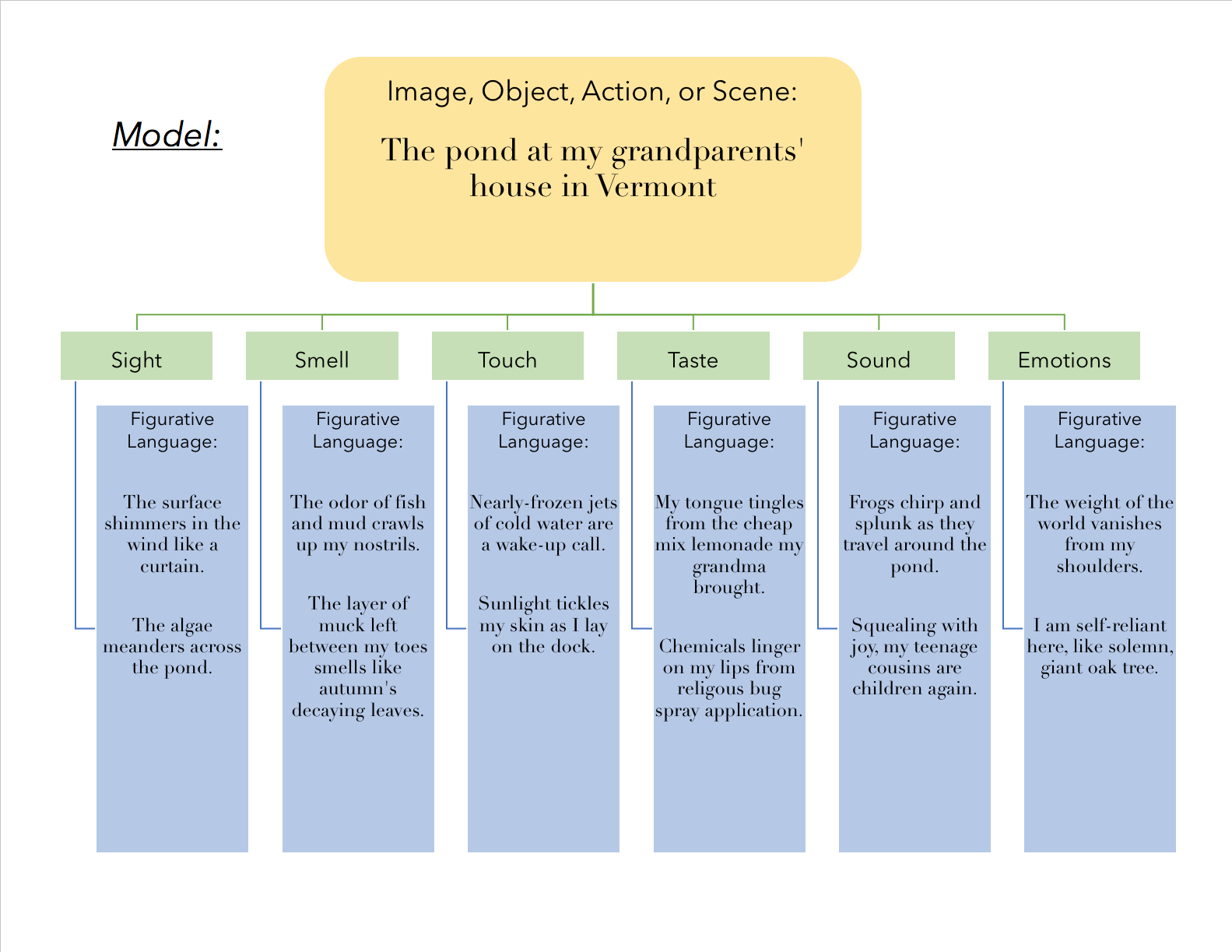

This exercise encourages you to experiment with thick description by focusing on one element of your writing in expansive detail. Read the directions below, then use the graphic organizer on the following two pages or write your responses as an outline on a separate piece of paper.

Identify one image, object, action, or scene that you want to expand in your story. Name this element in the big, yellow bubble.

Develop at least three describing words for your element, considering each sense independently, as well as emotional associations. Focus on particularities. (Adjectives will come most easily, but remember that you can use any part of speech.)

Then, on the next page, create at least two descriptions using figurative language (metaphor, simile, personification, onomatopoeia, hyperbole, etc.) for your element, considering each sense independently, as well as emotional associations. Focus on particularities.

Finally, reflect on the different ideas you came up with.

Which descriptions surprised you? Which descriptions are accurate but unanticipated?

Where might you weave these descriptions in to your current project?

How will you balance description with other rhetorical modes, like narration, argumentation, or analysis?

Repeat this exercise as desired or as instructed, choosing a different focus element to begin with.

Choose your favorite descriptors and incorporate them into your writing.

If you’re struggling to get started, check out the example on the pages following the blank organizer.

Model Texts by Student Authors

Innocence Again12

Imagine the sensation of the one split second that you are floating through the air as you were thrown up in the air as a child, that feeling of freedom and carefree spirit as happiness abounds. Looking at the world through innocent eyes, all thoughts and feelings of amazement. Being free, happy, innocent, amazed, wowed. Imagine the first time seeing the colors when your eyes and brain start to recognize them but never being able to name the shade or hue. Looking at the sky as it changes from the blackness with twinkling stars to the lightest shade of blue that is almost white, then the deep red of the sunset and bright orange of the sun. All shades of the spectrum of the rainbow, colors as beautiful as the mind can see or imagine.

I have always loved the sea since I was young; the smell of saltiness in the air invigorates me and reminds me of the times spent with my family enjoying Sundays at the beach. In Singapore, the sea was always murky and green but I continued to enjoy all activities in it. When I went to Malaysia to work, I discovered that the sea was clear and blue and without hesitation, I signed up for a basic diving course and I was hooked. In my first year of diving, I explored all the dive destinations along the east coast of Malaysia and also took an advanced diving course which allowed me to dive up to a depth of thirty meters. Traveling to a dive site took no more than four hours by car and weekends were spent just enjoying the sea again.

Gearing up is no fun. Depending on the temperature of the water, I might put on a shortie, wetsuit or drysuit. Then on come the booties, fins and mask which can be considered the easiest part unless the suit is tight—then it is a hop and pull struggle, which reminds me of how life can be at times. Carrying the steel tank, regulator, buoyancy control device (BCD) and weights is a torture. The heaviest weights that I ever had to use were 110 pounds, equivalent to my body weight; but as I jump in and start sinking into the sea, the contrast to weightlessness hits me. The moment that I start floating in the water, a sense of immense freedom and joy overtakes me.

Growing up, we have to learn the basics: time spent in classes to learn, constantly practicing to improve our skills while safety is ingrained by our parents. In dive classes, I was taught to never panic or do stupid stuff: the same with the lessons that I have learned in life. Panic and over-inflated egos can lead to death, and I have heard it happens all the time. I had the opportunity to go to Antarctica for a diving expedition, but what led to me getting that slot was the death of a very experienced diver who used a drysuit in a tropic climate against all advice. He just overheated and died. Lessons learned in the sea can be very profound, but they contrast the life I live: risk-taker versus risk-avoider. However, when I have perfected it and it is time to be unleashed, it is time to enjoy. I jump in as I would jump into any opportunity, but this time it is into the deep blue sea of wonders.

A sea of wonders waits to be explored. Every journey is different: it can be fast or slow, like how life takes me. The sea decides how it wants to carry me; drifting fast with the currents so that at times, I hang on to the reef and corals like my life depends on it, even though I am taught never to touch anything underwater. The fear I feel when I am speeding along with the current is that I will be swept away into the big ocean, never to be found. Sometimes, I feel like I am not moving at all, kicking away madly until I hyperventilate because the sea is against me with its strong current holding me against my will.

The sea decides what it wants me to see: turtles popping out of the seabed, manta rays gracefully floating alongside, being in the middle of the eye of a barracuda hurricane, a coral shelf as big as a car, a desert of bleached corals, the emptiness of the seabed with not a fish in sight, the memorials of death caused by the December 26

tsunami—a barren sea floor with not a soul or life in sight.

The sea decides what treasures I can discover: a black-tipped shark sleeping in an underwater cavern, a pike hiding from predators in the reef, an octopus under a dead tree trunk that escapes into my buddy’s BCD, colorful mandarin fish mating at sunset, a deadly box jellyfish held in my gloved hands, pygmy seahorses in a fern—so tiny that to discover them is a journey itself.

Looking back, diving has taught me more about life, the ups and downs, the good and bad, and to accept and deal with life’s challenges. Everything I learn and discover

underwater applies to the many different aspects of my life. It has also taught me that life is very short: I have to live in the moment or I will miss the opportunities that come my way. I allow myself to forget all my sorrow, despair and disappointments when I dive into the deep blue sea and savor the feelings of peacefulness and calmness. There is nothing around me but fish and corals, big and small. Floating along in silence with only the sound of my breath—inhale and exhale. An array of colors explodes in front of my eyes, colors that I never imagine I will discover again, an underwater rainbow as beautiful as the rainbow in the sky after a storm. As far as my eyes can see, I look into the depth of the ocean with nothing to anchor me. The deeper I get, the darker it turns. From the light blue sky to the deep navy blue, even blackness into the void. As the horizon darkens, the feeding frenzy of the underwater world starts and the watery landscape comes alive. Total darkness surrounds me but the sounds that I can hear are the little clicks in addition to my breathing. My senses overload as I cannot see what is around me, but the sea tells me it is alive and it anchors me to the depth of my soul.

As Ralph Waldo Emerson once said: “The lover of nature is he whose inward and outward senses are truly adjusted to each other; who has retained the spirit of

infancy even into the era of manhood… In the presence of nature, a wild delight runs through the man in spite of real sorrows….” The sea and diving have given me a new outlook on life, a different planet where I can float into and enjoy as an adult, a new, different perspective on how it is to be that child again. Time and time again as I enter into the sea, I feel innocent all over again.

Teacher Takeaways

“One of the more difficult aspects of writing a good descriptive essay is to use the description to move beyond itself — to ‘think through writing.’ This author does it well. Interspersed between the details of diving are deliberate metaphors and analogies that enable the reader to gain access and derive deeper meanings. While the essay could benefit from a more structured system of organization and clearer unifying points, and while the language is at times a bit sentimental, this piece is also a treasure trove of sensory imagery (notably colors) and descriptive devices such as personification and recursion.”– Professor Fiscaletti

Comatose Dreams13

Her vision was tunneled in on his face. His eyes were wet and his mouth was open as if he was trying to catch his breath. He leaned in closer and wrapped his arms around her face and spoke to her in reassuring whispers that reminded her of a time long ago when he taught her to pray. As her vision widened the confusion increased. She could not move. She opened her mouth to speak, but could not. She wanted to sit up, but was restrained to the bed. She did not have the energy to sob, but she could feel tears roll down her cheek and didn’t try to wipe them away. The anxiety overtook her and she fell back into a deep sleep.

She opened her eyes and tried to find reality. She was being tortured. Her feet were the size of pumpkins and her stomach was gutted all the way up her abdomen, her insides exposed for all to see. She was on display like an animal at the zoo. Tubes were coming out of her in multiple directions and her throat felt as if it were coated in chalk. She was conscious, but still a prisoner. Then a nurse walked in, pulled on one of her tubes, and sent her back into the abyss.

Eventually someone heard her speak, and with that she learned that if she complained enough she would get an injection. It gave her a beautiful head rush that temporarily dulled the pain. She adored it. She was no longer restrained to the bed, but still unable to move or eat. She was fed like baby. Each time she woke she was able to gather bits of information: she would not be going back to work, or school. couch was her safe haven. She came closer to dying during recovery than she had in the coma. The doctors made a mistake. She began to sweat profusely and shiver all at the same time. She vomited every twenty minutes like clockwork. It went on like that for days and she was ready to go. She wanted to slip back into her sleep. It was time to wake up from this nightmare. She pulled her hair and scratched her wrists trying to draw blood, anything to shake herself awake.

She began to heal. They removed a tube or two and she became more mobile. She was always tethered to a machine, like a dog on a leash. The pain from the surgeries still lingered and the giant opening in her stomach began to slowly close. The couch was her safe haven. She came closer to dying during recovery than she had in the coma. The doctors made a mistake. She began to sweat profusely and shiver all at the same time. She vomited every twenty minutes like clockwork. It went on like that for days and she was ready to go. She wanted to slip back into her sleep. It was time to wake up from this nightmare. She pulled her hair and scratched her wrists trying to draw blood, anything to shake herself awake.

She sat on a beach remembering that nightmare. The sun beat down recharging a battery within her that had been running on empty for far too long. The waves washed up the length of her body and she sank deeper into the warm sand. She lay on her back taking it all in. Then laid her hand on top of her stomach, unconsciously she ran her fingers along a deep scar.

Teacher Takeaways

“This imagery is body-centered and predominantly tactile — though strange sights and sounds are also present. The narrow focus of the description symbolically mirrors the limitation of the comatose subject, which enhances the reader’s experience. Simile abounds, and in its oddities (feet like pumpkins, something like chalk in the throat), adds to the eerie newness of each scene. While the paragraphs are a bit underdeveloped, and one or two clichés in need of removal, this little episode does an excellent job of conveying the visceral strangeness one might imagine to be associated with a comatose state. It’s full of surprise.”– Professor Fiscaletti

The Devil in Green Canyon14

The sky was painted blue, with soft wisps of white clouds that decorated the edges of the horizon like a wedding cake. To the West, a bright orb filled the world with warm golden light which gives life to the gnarled mountain landscape. The light casted contrasting shadows against the rolling foot hills of the Cascade Mountain Range. A lone hawk circled above the narrow white water river that lay beneath the steep mountain side. Through the hawk’s eyes the mountains look like small green waves that flow down from a massive snow white point. Mt. Hood sits high above its surrounding foot hills, like that special jewel that sits on a pedestal, above all the others in a fancy jewelry store. The hawk soars into the Salmon River Valley, with hope of capturing a tasty meal, an area also known as the Green Canyon.

For hundreds of years, the Salmon River has carved its home into the bedrock. Filled from bank to bank with tumbled boulders, all strewn across the river bed, some as big as a car. Crystal clear water cascades over and around the rocky course nature has made with its unique rapids and eddies for the native salmon and trout to navigate, flanked by thick old growth forest and the steep tree studded walls of the canyon. Along the river lies a narrow two-lane road, where people are able to access tall wonders of this wilderness. The road was paved for eight miles and the condition was rough, with large potholes and sunken grades.

In my beat up old Corolla, I drove down windy roads of the Salmon River. With the windows down and the stereo turned up, I watched trees that towered above me pass behind my view. A thin ribbon of blue sky peeked through the towering Douglas Fir and Sequoia trees. At a particular bend in the road, I drove past an opening in the trees. Here the river and the road came around a sharp turn in the canyon. A natural rock face, with a patch of gravel at its base, offered a place to park and enjoy the river. The water was calm and shallow, like a sheet of glass. I could see the rocky bottom all the way across the river, the rocks were round and smoothed by the continuous flow of water. It was peaceful as gentle flow of water created this tranquil symphony of rippling sounds.

As the road continued up the gentle slope guarded on the right by a thicket of bushes and tall colorful wild flowers giving red, purple, and white accents against lush green that dominated the landscape, followed by tall trees that quickly give way to a rocky precipice to the left. A yellow diamond shaped sign, complete with rusty edges and a few bullet holes indicated a one-lane bridge ahead. This was it! The beginning of the real journey. I parked my dusty Corolla as the gravel crunched under the balding tires, they skidded to a stop. As I turned the engine off, its irregular hum sputtered into silence. I could smell that hot oil that leaked from somewhere underneath the motor. I hopped out of the car and grabbed my large-framed backpack which was filled with enough food and gear for a few nights, I locked the car and took a short walk down the road. I arrived at the trail head, I was here to find peace, inspiration and discover a new place to feel freedom.

Devil’s Peak. 16 miles. As the trail skirted its way along the cascading Salmon River. The well-traveled dirt path was packed hard by constant foot traffic with roots from the massive old fir trees, rocks and mud that frequently created tripping hazards along the trail. Sword Fern, Salmon Berry and Oregon Grape are among the various small plant growth that lined the trail. Under the shade of the thick canopy, the large patches of shamrocks created an even covering over the rolling forest floor like the icing on a cake. The small shamrock forests are broken by mountainous nursery logs of old decaying trees. New life sprouts as these logs nature and host their kin. Varieties of maple fight for space among the ever-growing conifers that dominate the forest. Vine maple arches over the trail, bearded with hanging moss that forms natural pergolas.

It is easy to see why it is named Green Canyon, as the color touches everything. From the moss covering the floor, to the tops of the trees, many hues of green continue to paint the forest. These many greens are broken by the brown pillar like trunks of massive trees. Their rough bark provides a textural contrast to the soft leaves and pine needles. Wild flowers grow between the sun breaks in the trees and provide a rainbow of color. Near the few streams that form from artesian springs higher up, vicious patches of devil’s glove, create a thorny wall that can tower above the trail. Their green stalk bristling with inch long barbs and the large leaves some over a foot long are covered with smaller needles.

I can hear the hum of bees in the distance collecting pollen from the assorted wild flowers. Their buzz mixes in with the occasional horse fly that lumbers past. For miles the trail, follows the river before it quickly ascends above the canyon. Winding steeply away from the river, the sound of rushing water began to fade, giving way to the serene and eerie quiet of the high mountains. Leaves and trees make a gentle sound as the wind brushes past them, but are overpowered by the sound of my dusty hiking boots slowly dragging me up this seemingly never-ending hill. I feel tired and sweat is beading up on my brow, exhausted as I am, I feel happy and relieved. Its moments like this that recharge the soul. I continue to climb, sweat and smile.

Undergrowth gives way to the harsh steep rock spires that crown the mountain top like ancient vertebra. The forest opens up to a steep cliff with a clearing offering a grand view. The spine of the mountain is visible, it hovers at 5000 feet above sea level and climbs to a point close to 5200 feet. Trees fight for position on the steep hillside as they flow down to the edge of the Salmon River. This a popular turn around point for day hikes. Not for me; I am going for the top. The peak is my destination where I will call home tonight. Devil’s Peak is a destination. Not just a great view point but it is also home to a historic fire watchtower. Here visitors can explore the tower and even stay the night.

From the gorge viewpoint the trail switchbacks up several miles through dense high-altitude forests. Passing rocky ramparts and a few sheer cliff faces the path ends at an old dirt road with mis from bygone trucks that leave faint traces of life. A hand carved wooden sign, nailed to a tree at the continuation of the trail indicates another 2.6 miles to Devil’s Peak. The trail is narrow as it traces the spine of the mountain before steeply carving around the peak. There are instances where the mountain narrows to a few feet, with sheer drops on both sides, like traversing a catwalk. The trees at this altitude are stunted compared to the giants that live below. Most trees here are only a foot or two thick and a mere 50 feet in height. The thick under growth has dwindled to small rhododendron bushes and clumps of bear grass. The frequently gusting wind has caused the trunks of the trees to grow into twisted gnarled forms. It is almost like some demon walked through the trail distorting everything as it passed. Foxglove and other wild flowers find root holds in warm sunny spots along the trail. Breaks in the thick forest provide snapshots of distant mountains: Mt. Hood is among the snowcapped peaks that pepper the distant mountains.

With sweat on my brow, forming beads that drip down my face, I reached the top. The trail came to a fork where another small sign indicates to go left. After a few feet the forest shrinks away and opens to a rocky field with expansive views that stretched for miles. There, standing its eternal watch, is the Devil’s Peak watch tower. Its sun-bleached planks are a white contrast to the evergreen wall behind it. It was built by hand decades ago before portable power tools by hardened forest rangers. It has stood so long that the peak which once offered a 360-degree view now only has a few openings left between the mature trees that surround the grove in which the old devil stands, watching high above the green canyon. The lookout stands 30 feet in height. Its old weathered moss-covered wood shingled roof is topped with a weathered copper lightning rod. A staircase climbs steeply to the balcony that wraps around the tower. Only two feet wide, the deck still offers an amazing view where the forest allows. Mt. Hood stands proud to the North and the green mountains stretch South to the edge of the horizon.

The builders made window covers to protect the glass during storms. Once lined and supported with boards that have been notched to fit the railing, the tower is open filling the interior with daylight. In all the cabin is only twelve feet by twelve feet. The door has a tall window and three of the four walls have windows most of the way to the ceiling. The furnishing is modest, with a bed that has several pieces of foam and some sleeping bags to make mattress, it was complete with a pillow with no case. A table covered with carvings and some useful information and rules for the tower were taped to the surface. An old diary for the tower and a cup full of writing instruments next to it for visitors to share their experience lay closed in the middle of the table. In the South East corner, on a hearth made of old brick sat an old iron wood stove. The door had an image of a mountain and trees molded into it. The top was flat and had room to use for a cook top. Someone left a small pile of wood next the stove. The paint on the inside was weathered and stripping. The floor boards creaked with each step. Whenever the wind gusted the windows rattled. The air inside the cabin was musty and dry. It smelled old. But the windows all pivot and open to make the inside feel like its outside and as soon as the windows were opened the old smell is replaced with the scent of fresh pine.

Surrounded by small patches of wild flowers and rocks, all ringed by a maturing forest Devil’s Peak watchtower sits high above the Green Canyon. On a high point near the tower where solid rock pierces the ground there is a small round plaque cemented to the ancient basalt. It is a U.S. geological marker with the name of the peak and its elevation stamped into the metal. Standing on the marker I can see south through a large opening in the trees. Mountains like giant green walls fill the view. For miles, rock and earth rise up forming mountains, supporting the exquisite green forest.

The hawk circles, soaring high above the enchanting mountains. On a peak below, it sees prey skitter across a rock into a clump of juniper and swoops down for the hunt. There I stand on the tower’s wooden balcony, watching the sunset. The blue horizon slowly turned pale before glowing orange. Mt. Hood reflected the changing colors, from orange to a light purple. Soon stars twinkled above and the mountain faded to dark. The day is done. Here in this moment, I am.

Teacher Takeaways

“This author’s description is frequent and rich with detail; I especially like the thorough inventory of wildlife throughout the essay, although it does get a feel a bit burdensome at times. I can clearly envision the setting, at times even hearing the sounds and feeling the textures the author describes. Depending on their goals in revision, this author might make some global adjustments to pacing (so the reader can move through a bit more quickly and fluidly). At the very least, this student should spend some time polishing up mechanical errors. I noticed two recurring issues: (1) shifting verb tense [the author writes in both present and past tense, where it would be more appropriate to stick with one or the other]; and (2) sentence fragments, run-ons, and comma splices [all errors that occur because a sentence combines clauses ungrammatically].”– Professor Wilhjelm

Endnotes

a writing technique by which an author tries to follow a rule or set of rules in order to create more experimental or surprising content, popularized by the Oulipo school of writers.

a rhetorical mode that emphasizes eye-catching, specific, and vivid portrayal of a subject. Often integrates imagery and thick description to this end.

a method of reading, writing, and thinking that emphasizes the interruption of automatization. Established as “остранение” (“estrangement”) by Viktor Shklovsky, defamiliarization attempts to turn the everyday into the strange, eye-catching, or dramatic.

a study of a particular culture, subculture, or group of people. Uses thick description to explore a place and its associated culture.

language which implies a meaning that is not to be taken literally. Common examples include metaphor, simile, personification, onomatopoeia, and hyperbole.

sensory language; literal or figurative language that appeals to an audience’s imagined sense of sight, sound, smell, touch, or taste.

economical and deliberate language which attempts to capture complex subjects (like cultures, people, or environments) in written or spoken language. Coined by anthropologists Clifford Geertz and Gilbert Ryle.