Chapter Seven: Argumentation

To a nonconfrontational person (like me), argument is a dirty word. It surfaces connotations of raised voices, slammed doors, and dominance; it arouses feelings of anxiety and frustration.

But argument is not inherently bad. In fact, as a number of great thinkers have described, conflict is necessary for growth, progress, and community cohesion. Through disagreement, we challenge our commonsense assumptions and seek compromise. The negative connotations surrounding ‘argument’ actually point to a failure in the way that we argue.

Check out this video on empathy: it provides some useful insight to the sort of listening, thinking, and discussion required for productive arguments.

Now, spend a few minutes reflecting on the last time you had an argument with a loved one. What was it about? What was it really about? What made it difficult? What made it easy?

Often, arguments hinge on the relationship between the arguers: whether written or verbal, that argument will rely on the specific language, approach, and evidence that each party deems valid. For that reason, the most important element of the rhetorical situation is audience. Making an honest, impactful, and reasonable connection with that audience is the first step to arguing better.

Unlike the argument with your loved one, it is likely that your essay will be establishing a brand-new relationship with your reader, one which is untouched by your personal history, unspoken bonds, or other assumptions about your intent. This clean slate is a double-edged sword: although you’ll have a fresh start, you must more deliberately anticipate and navigate your assumptions about the audience. What can you assume your reader already knows and believes? What kind of ideas will they be most swayed by? What life experiences have they had that inform their worldview?

This chapter will focus on how the answers to these questions can be harnessed for productive, civil, and effective arguing. Although a descriptive personal narrative (Section 1) and a text wrestling analysis (Section 2) require attention to your subject, occasion, audience, and purpose, an argumentative essay is the most sensitive to rhetorical situation of the genres covered in this book. As you complete this unit, remember that you are practicing the skills necessary to navigating a variety of rhetorical situations: thinking about effective argument will help you think about other kinds of effective communication.

Chapter Vocabulary

|

Vocabulary |

Definition |

|

a rhetorical mode in which different perspectives on a common issue are negotiated. See Aristotelian and Rogerian arguments. |

|

|

a mode of argument by which a writer attempts to convince their audience that one perspective is accurate. |

|

|

the intended consumers for a piece of rhetoric. Every text has at least one audience; sometimes, that audience is directly addressed, and other times we have to infer. |

|

|

a persuasive writer’s directive to their audience; usually located toward the end of a text. Compare with purpose. |

|

|

a rhetorical appeal based on authority, credibility, or expertise. |

|

|

the setting (time and place) or atmosphere in which an argument is actionable or ideal. Consider alongside “occasion.” |

|

|

a line of logical reasoning which follows a pattern of that makes an error in its basic structure. For example, Kanye West is on TV; Animal Planet is on TV. Therefore, Kanye West is on Animal Planet. |

|

|

a rhetorical appeal to logical reasoning. |

|

|

a neologism from ‘impartial,’ refers to occupying and appreciating a variety of perspectives rather than pretending to have no perspective. Rather than unbiased or neutral, multipartial writers are balanced, acknowledging and respecting many different ideas. |

|

|

a rhetorical appeal to emotion. |

|

|

a means by which a writer or speaker connects with their audience to achieve their purpose. Most commonly refers to logos, pathos, and ethos. |

|

|

a mode of argument by which an author seeks compromise by bringing different perspectives on an issue into conversation. Acknowledges that no one perspective is absolutely and exclusively ‘right’; values disagreement in order to make moral, political, and practical decisions. |

|

|

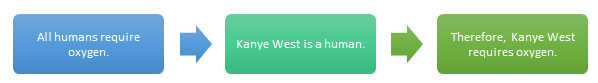

a line of logical reasoning similar to the transitive property (If a=b and b=c, then a=c). For example, All humans need oxygen; Kanye West is a human. Therefore, Kanye West needs oxygen. |

|

Techniques

“But I Just Want to Write an Unbiased Essay”

Let’s begin by addressing a common concern my students raise when writing about controversial issues: neutrality. It’s quite likely that you’ve been trained, at some point in your writing career, to avoid bias, to be objective, to be impartial. However, this is a habit you need to unlearn, because every text is biased by virtue of being rhetorical. All rhetoric has a purpose, whether declared or secret, and therefore is partial.

Instead of being impartial, I encourage you to be multipartial. In other words, you should aim to inhabit many different positions in your argument—not zero, not one, but many. This is an important distinction: no longer is your goal to be unbiased; rather, it is to be balanced. You will not provide your audience a neutral perspective, but rather a perspective conscientious of the many other perspectives out there.

Common Forms of Argumentation

In the study of argumentation, scholars and authors have developed a great variety of approaches: when it comes to convincing, there are many different paths that lead to our destination. For the sake of succinctness, we will focus on two: the Aristotelian argument and the Rogerian Argument.1 While these two are not opposites, they are built on different values. Each will employ rhetorical appeals like those discussed later, but their purposes and guiding beliefs are different.

Aristotelian Argument

In Ancient Greece, debate was a cornerstone of social life. Intellectuals and philosophers devoted hours upon hours of each day to honing their argumentative skills. For one group of thinkers, the Sophists, the focus of argumentation was to find a distinctly “right” or “wrong” position. The more convincing argument was the right one: the content mattered less than the technique by which it was delivered.

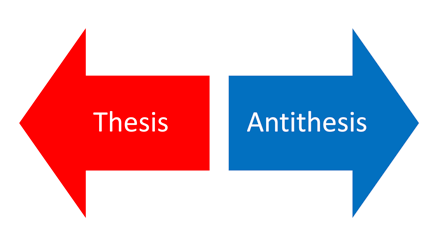

In turn, the purpose of an Aristotelian argument is to persuade someone (the other debater and/or the audience) that the speaker was correct. Aristotelian arguments are designed to bring the audience from one point of view to the other.

In this diagram, you can observe the tension between a point and counterpoint (or, to borrow a term from German philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte, “thesis” and “antithesis.”) These two viewpoints move in two opposite directions, almost like a tug-of-war.

In this diagram, you can observe the tension between a point and counterpoint (or, to borrow a term from German philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte, “thesis” and “antithesis.”) These two viewpoints move in two opposite directions, almost like a tug-of-war.

Therefore, an Aristotelian arguer tries to demonstrate the validity of their direction while addressing counterarguments: “Here’s what I believe and why I’m right; here’s what you believe and why it’s wrong.” The author seeks to persuade their audience through the sheer virtue of their truth.

You can see Aristotelian argumentation applied in “We Don’t Care about Child Slaves.”

Rogerian Argument

In contrast, Rogerian arguments are more invested in compromise. Based on the work of psychologist Carl Rogers, Rogerian arguments are designed to enhance the connection between both sides of an issue. This kind of argument acknowledges the value of disagreement in material communities to make moral, political, and practical decisions.

Often, a Rogerian argument will begin with a fair statement of someone else’s position and consideration of how that could be true. In other words, a Rogerian arguer addresses their ‘opponent’ more like a teammate: “What you think is not unreasonable; I disagree, but I can see how you’re thinking, and I appreciate it.” Notice that by taking the other ideas on their own terms, you demonstrate respect and cultivate trust and listening.

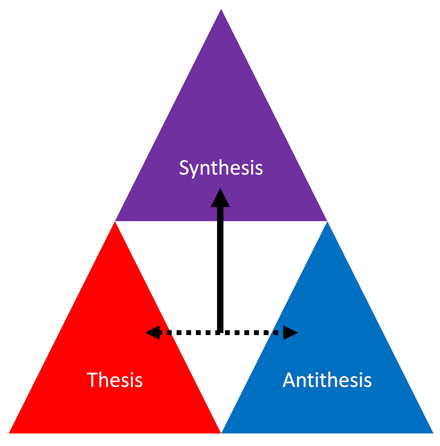

The rhetorical purpose of a Rogerian argument, then, is to come to a conclusion by negotiating common ground between moral-intellectual differences. Instead of

debunking an opponent’s counterargument entirely, a Rogerian arguer would say, “Here’s what each of us thinks, and here’s what we have in common. How can we proceed forward to honor our shared beliefs but find a new, informed position?” In Fichte’s model of thesis-antithesis-synthesis,2 both debaters would pursue synthesis. The author seeks to persuade their audience by showing them respect, demonstrating a willingness to compromise, and championing the validity of their truth as one among other valid truths.

debunking an opponent’s counterargument entirely, a Rogerian arguer would say, “Here’s what each of us thinks, and here’s what we have in common. How can we proceed forward to honor our shared beliefs but find a new, informed position?” In Fichte’s model of thesis-antithesis-synthesis,2 both debaters would pursue synthesis. The author seeks to persuade their audience by showing them respect, demonstrating a willingness to compromise, and championing the validity of their truth as one among other valid truths.

The thesis is an intellectual proposition.

The antithesis is a critical perspective on the thesis.

The synthesis solves the conflict between the thesis and antithesis by reconciling their common truths and forming a new proposition.

You can see Rogerian argumentation applied in “Vaccines: Controversies and Miracles.”

|

Position |

Aristotelian |

Rogerian |

|

Wool sweaters are the best clothing for cold weather. |

Wool sweaters are the best clothing for cold weather because they are fashionable and comfortable. Some people might think that wool sweaters are itchy, but those claims are ill-informed. Wool sweaters can be silky smooth if properly handled in the laundry. |

Some people might think that wool sweaters are itchy, which can certainly be the case. I’ve worn plenty of itchy wool sweaters. But wool sweaters can be silky smooth if properly handled in the laundry; therefore, they are the best clothing for cold weather. If you want to be cozy and in-style, consider my laundry techniques and a fuzzy wool sweater. |

Before moving on, try to identify one rhetorical situation in which Aristotelian argumentation would be most effective, and one in which Rogerian argumentation would be preferable. Neither form is necessarily better, but rather both are useful in specific contexts. In what situations might you favor one approach over another?

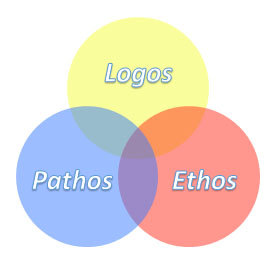

Rhetorical Appeals

Regardless of the style of argument you use, you will need to consider the ways you engage your audience. Aristotle identified three kinds of rhetorical appeals: logos, pathos, and ethos. Some instructors refer to this trio as the “rhetorical triangle,” though I prefer to think of them as a three-part Venn diagram.3 The best argumentation engages all three of these appeals, falling in the center where all three overlap. Unbalanced application of rhetorical appeals is likely to leave your audience suspicious, doubtful, or even bored.

Logos

You may have inferred already, but logos refers to an appeal to an audience’s logical reasoning. Logos will often employ statistics, data, or other quantitative facts to demonstrate the validity of an argument. For example, an argument about the wage gap might indicate that women, on average, earn only 80 percent of the salary that men in comparable positions earn; this would imply a logical conclusion that our economy favors men.

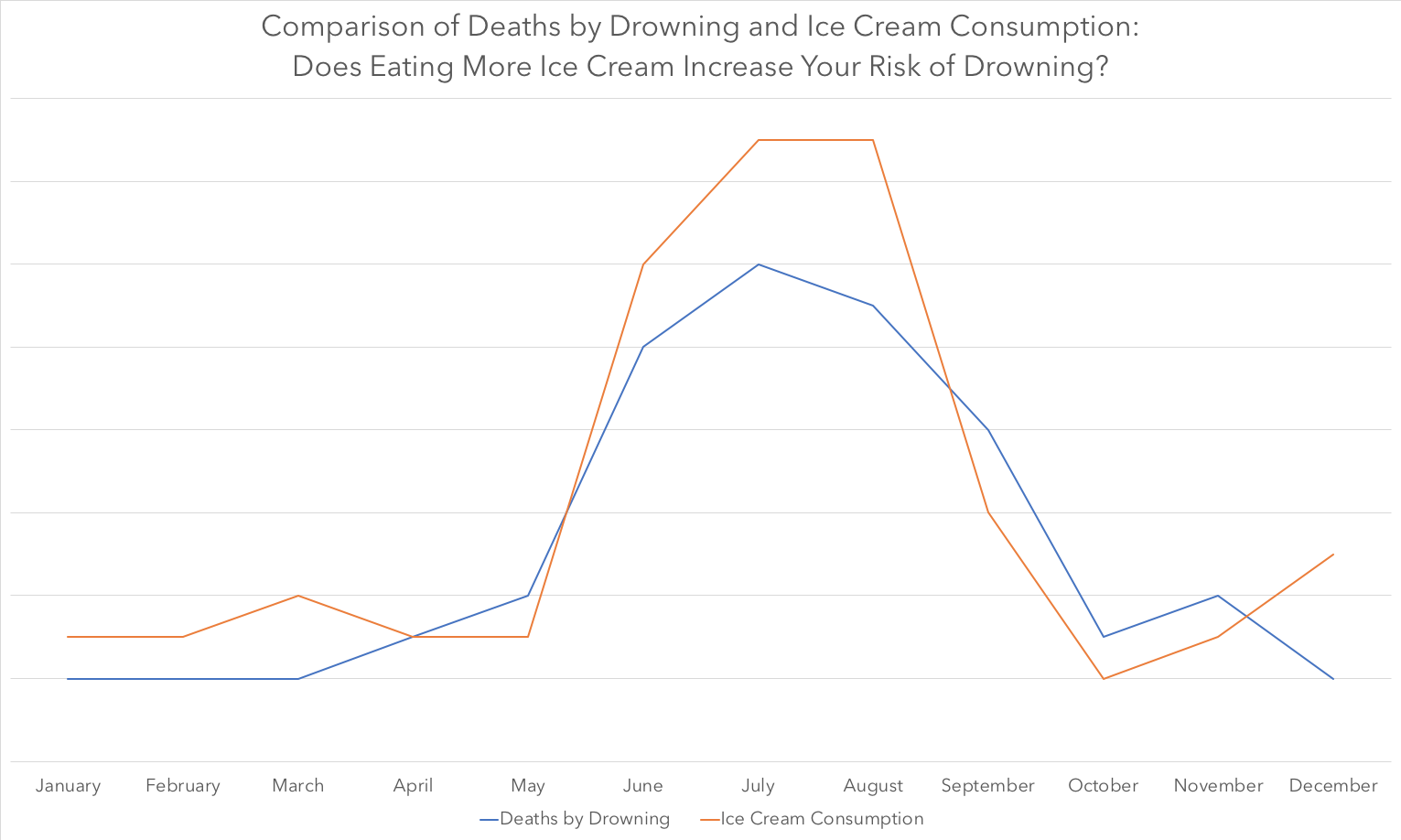

However, stating a fact or statistic does not alone constitute logos. For instance, when I show you this graph4, I am not yet making a logical appeal:

Yes, the graph is “fact-based,” drawing on data to illustrate a phenomenon. That characteristic alone, though, doesn’t make a logical appeal. For my appeal to be logical, I also need to interpret the graph:

As is illustrated here, there is a direct positive correlation between ice cream consumption and deaths by drowning: when people eat more ice cream, more people drown. Therefore, we need to be more careful about waiting 30 minutes after we eat ice cream.

Of course, this conclusion is inaccurate; it is a logical fallacy described in the table below called “post hoc, ergo propter hoc.” However, the example illustrates that your logic is only complete when you’ve drawn a logical conclusion from your facts, statistics, or other information.

There are many other ways we draw logical conclusions. There are entire branches of academia dedicated to understanding the many kinds of logical reasoning, but we might get a better idea by looking at a specific kind of logic. Let’s take for example the logical syllogism, which might look something like this:

Pretty straightforward, right? We can see how a general rule (major premise) is applied to a specific situation (minor premise) to develop a logical conclusion. I like to introduce this kind of logic because students sometimes jump straight from the major premise to the conclusion; if you skip the middle step, your logic will be less convincing.

It does get a little more complex. Consider this false syllogism: it follows the same structure (general rule + specific situation), but it reaches an unlikely conclusion.

This is called a logical fallacy. Logical fallacies are part of our daily lives. Stereotypes, generalizations, and misguided assumptions are fallacies you’ve likely encountered. You may have heard some terms about fallacies already: red herring, slippery slope, non sequitur. Fallacies follow patterns of reasoning that would otherwise be perfectly acceptable to us, but within their basic structure, they make a mistake. Aristotle identified that fallacies happen on the “material” level (the content is fallacious—something about the ideas or premises is flawed) and the “verbal” level (the writing or speech is fallacious—something about the delivery or medium is flawed).

It’s important to be able to recognize these so that you can critically interrogate others’ arguments and improve your own. Here are some of the most common logical fallacies:

|

Fallacy |

Description |

Example |

|

Post hoc, ergo propter hoc |

“After this, therefore because of this” – a confusion of cause-and-effect with coincidence, attributing a consequence to an unrelated event. This error assumes that correlation equals causation, which is sometimes not the case. |

Statistics show that rates of ice cream consumption and deaths by drowning both increased in June. This must mean that ice cream causes drowning. |

|

Non sequitur |

“Does not follow” – a random digression that distracts from the train of logic (like a “red herring”), or draws an unrelated logical conclusion. John Oliver calls one manifestation of this fallacy “whataboutism,” which he describes as a way to deflect attention from the subject at hand. |

Sherlock is great at solving crimes; therefore, he’ll also make a great father. Sherlock Holmes smokes a pipe, which is unhealthy. But what about Bill Clinton? He eats McDonald’s every day, which is also unhealthy. |

|

Straw Man |

An oversimplification or cherry-picking of the opposition’s argument to make them easier to attack. |

People who oppose the destruction of Confederate monuments are all white supremacists. |

|

Ad hominem |

“To the person” – a personal attack on the arguer, rather than a critique of their ideas. |

I don’t trust Moriarty’s opinion on urban planning because he wears bowties. |

|

Slippery Slope |

An unreasonable prediction that one event will lead to a related but unlikely series of events that follows. |

If we let people of the same sex get married, then people will start marrying their dogs too! |

|

False Dichotomy |

A simplification of a complex issue into only two sides. |

Given the choice between pizza and Chinese food for dinner, we simply must choose Chinese. |

|

Learn about other logical fallacies in the Additional Recommended Resources appendix. |

||

Pathos

The second rhetorical appeal we’ll consider here is perhaps the most common: pathos refers to the process of engaging the reader’s emotions. (You might recognize the Greek root pathos in “sympathy,” “empathy,” and “pathetic.”) A writer can evoke a great variety of emotions to support their argument, from fear, passion, and joy to pity, kinship, and rage. By playing on the audience’s feelings, writers can increase the impact of their arguments.

There are two especially effective techniques for cultivating pathos that I share with my students:

- Make the audience aware of the issue’s relevance to them specifically—“How would you feel if this happened to you? What are we to do about this issue?”

- Tell stories. A story about one person or one community can have a deeper impact than broad, impersonal data or abstract, hypothetical statements. Consider the difference between

About 1.5 million pets are euthanized each year

and

Scooter, an energetic and loving former service dog with curly brown hair like a Brillo pad, was put down yesterday.

Both are impactful, but the latter is more memorable and more specific.

Pathos is ubiquitous in our current journalistic practices because people are more likely to act (or, at least, consume media) when they feel emotionally moved.5 Consider, as an example, the outpouring of support for detained immigrants in June 2018, reacting to the Trump administration’s controversial family separation policy. As stories and images like this one surfaced, millions of dollars were raised in a matter of days on the premise of pathos, and resulted in the temporary suspension of that policy.

Ethos

Your argument wouldn’t be complete without an appeal to ethos. Cultivating ethos refers to the means by which you demonstrate your authority or expertise on a topic. You’ll have to show your audience that you’re trustworthy if they are going to buy your argument.

There are a handful of ways to demonstrate ethos:

- By personal experience: Although your lived experience might not set hard-and-fast rules about the world, it is worth noting that you may be an expert on certain facets of your life. For instance, a student who has played rugby for fifteen years of their life is in many ways an authority on the sport.

- By education or other certifications: Professional achievements demonstrate ethos by revealing status in a certain field or discipline.

- By citing other experts: The common expression is “Stand on the shoulders of giants.” You can develop ethos by pointing to other people with authority and saying, “Look, this smart/experienced/qualified/important person agrees with me.”

A common misconception is that ethos corresponds with “ethics.” However, you can remember that ethos is about credibility because it shares a root with “authority.”

Sociohistorical Context of Argumentation

This textbook has emphasized consideration of your rhetorical occasion, but it bears repeating here that “good” argumentation depends largely on your place in time, space, and culture. Different cultures throughout the world value the elements of argumentation differently, and argument has different purposes in different contexts. The content of your argument and your strategies for delivering it will change in every unique rhetorical situation.

Continuing from logos, pathos, and ethos, the notion of kairos speaks to this concern. To put it in plain language, kairos is the force that determines what will be the best argumentative approach in the moment in which you’re arguing; it is closely aligned with rhetorical occasion. According to rhetoricians, the characteristics of the kairos determine the balance and application of logos, pathos, and ethos.

Moreover, your sociohistorical context will bear on what you can assume of your audience. What can you take for granted that your audience knows and believes? The “common sense” that your audience relies on is always changing: common sense in the U.S. in 1950 was much different from common sense in the U.S. in 1920 or common sense in the U.S. in 2018. You can make assumptions about your audience’s interests, values, and background knowledge, but only with careful consideration of the time and place in which you are arguing.

As an example, let’s consider the principle of logical noncontradiction. Put simply, this means that for an argument to be valid, its logical premises must not contradict one another: if A = B, then B = A. If I said that a dog is a mammal and a mammal is an animal, but a dog is not an animal, I would be contradicting myself. Or, “No one drives on I-84; there’s too much traffic.” This statement contradicts itself, which makes it humorous to us.

However, this principle of non-contradiction is not universal. Our understanding of cause and effect and logical consistency is defined by the millennia of knowledge that has been produced before us, and some cultures value the contradiction rather than perceive it as invalid.6 This is not to say that either way of seeing the world is more or less accurate, but rather to emphasize that your methods of argumentation depend tremendously on sociohistorical context.

Activities

Op-Ed Rhetorical Analysis

One form of direct argumentation that is readily available is the opinion editorial, or op-ed. Most news sources, from local to international, include an opinion section. Sometimes, these pieces are written by members of the news staff; sometimes, they’re by contributors or community members. Op-eds can be long (e.g., comprehensive journalistic articles, like Ta-Nehisi Coates’ landmark “The Case for Reparations”) or they could be brief (e.g., a brief statement of one’s viewpoint, like in your local newspaper’s Letter to the Editor section).

To get a better idea of how authors incorporate rhetorical appeals, complete the following rhetorical analysis exercise on an op-ed of your choosing.

Find an op-ed (opinion piece, editorial, or letter to the editor) from either a local newspaper, a national news source, or an international news corporation. Choose something that interests you, since you’ll have to read it a few times over.

- Read the op-ed through once, annotating parts that are particularly convincing, points that seem unsubstantiated, or other eye-catching details.

- Briefly (in one to two sentences) identify the rhetorical situation (SOAP) of the op-ed.

- Write a citation for the op-ed in an appropriate format.

- Analyze the application of rhetoric.

- Summarize the issue at stake and the author’s position.

- Find a quote that represents an instance of logos.

- Find a quote that represents an instance of pathos.

- Find a quote that represents an instance of ethos.

- Paraphrase the author’s call-to-action (the action or actions the author wants the audience to take). A call-to-action will often be related to an author’s rhetorical purpose.

- In a one-paragraph response, consider: Is this rhetoric effective? Does it fulfill its purpose? Why or why not?

VICE News Rhetorical Appeal Analysis

VICE News, an alternative investigatory news outlet, has recently gained acclaim for its inquiry-driven reporting on current issues and popular appeal, much of which is derived from effective application of rhetorical appeals.

You can complete the following activity using any of their texts, but I recommend “State of Surveillance” from June 8, 2016. Take notes while you watch and complete the organizer on the following pages after you finish.

|

What is the title and publication date of the text? |

|

Briefly summarize the subject of this text. |

|

How would you describe the purpose of this text? |

|

Pathos |

Provide at least 3 examples of pathos that you observed in the text: |

How would you describe the overall tone of the piece? What mood does it evoke for the viewer/reader? |

|

Logos |

Provide at least 3 examples of logos that you observed in the text: |

In addition to presenting data and statistics, how does the text logically interpret evidence? |

|

Ethos |

Provide at least 3 examples of ethos that you observed in the text: |

How might one person, idea, or source both enhance and detract from the cultivation of ethos? (Consider Edward Snowden in “State of Surveillance,” for instance.) |

Audience Analysis: Tailoring Your Appeals

Now that you’ve observed the end result of rhetorical appeals, let’s consider how you might tailor your own rhetorical appeals based on your audience.

First, come up with a claim that you might try to persuade an audience to believe. Then, consider how you might develop this claim based on the potential audiences listed in the organizer on the following pages. An example is provided after the empty organizer if you get stuck.

|

Claim: |

|

|

Audience #1: Business owners |

What assumptions might you make about this audience? What do you think they currently know and believe? |

|

Logos |

|

|

Pathos |

|

|

Ethos |

|

|

Audience #2: Local political officials |

What assumptions might you make about this audience? What do you think they currently know and believe? |

|

Logos |

|

|

Pathos |

|

|

Ethos |

|

|

Audience #3: One of your family members |

What assumptions might you make about this audience? What do you think they currently know and believe? |

|

Logos |

|

|

Pathos |

|

|

Ethos |

|

|

Audience #4: Invent your own

|

What assumptions might you make about this audience? What do you think they currently know and believe? |

|

Logos |

|

|

Pathos |

|

|

Ethos |

|

Model:

|

Claim: |

Employers should offer employees discounted or free public transit passes. |

|

|

Audience #1: Business owners |

What assumptions might you make about this audience? What do you think they currently know and believe? |

|

|

Logos |

They are concerned with profit margins – I need to show that this will benefit them financially: “If employees are able to access transportation more reliably, then they are more likely to arrive on time, which increases efficiency.” |

|

|

Pathos |

They are concerned with employee morale – I need to show that access will improve employee satisfaction: “Every employer wants their employees to feel welcome at the office. Does your work family dread the start of the day?” |

|

|

Ethos |

They are more likely to believe my claim if other business owners, the chamber of commerce, etc., back it up: “In 2010, Portland employer X started providing free bus passes, and their employee retention rate has increased 30%.” |

|

|

Audience #2: Local political officials |

What assumptions might you make about this audience? What do you think they currently know and believe? |

|

|

Logos |

They are held up by political bureaucracy – I need to show a clear, direct path to executing my claim: “The implementation of such a program could be modeled after an existing system, like EBT cards.” |

|

|

Pathos |

They are concerned with reelection – I need to show that this will build an enthusiastic voter base: “When politicians show concern for workers, their approval rates increase. If the voters are happy, you’ll be happy!” |

|

|

Ethos |

They are more likely to believe my claim if I show other cities and their political officials executing a similar plan – I could also draw on my own experiences because I am a member of the community they represent: “As an employee who uses public transit (and an enthusiastic voter), I can say that I would make good use of this benefit.” |

|

|

Audience #3: One of your family members |

What assumptions might you make about this audience? What do you think they currently know and believe? |

|

|

Logos |

My mom has to drive all over the state for her job – I could explain how this will benefit her: “If you had a free or discounted pass, you could drive less. Less time behind the wheel means a reduction of risk!” |

|

|

Pathos |

My mom has to drive all over the state for her job – I could tap into her frustration: “Aren’t you sick of a long commute bookending each day of work? The burning red glow of brakelights and the screech of tires—it doesn’t have to be this way.” |

|

|

Ethos |

My mom might take my word for it since she trusts me already: “Would I mislead you? I hate to say I told you so, but I was totally right about the wool sweater thing.” |

|

|

Audience #4: Invent your own Car drivers |

What assumptions might you make about this audience? What do you think they currently know and believe? |

|

|

Logos |

They are concerned with car-related expenses – I need to lay out evidence of savings from public transit: “Have you realized that taking the bus two days a week could save you $120 in gas per month?” |

|

|

Pathos |

They are frustrated by traffic, parking, etc. – I could play to that emotion: “Is that a spot? No. Is that a spot? No. Oh, but th—No. Sound familiar? You wouldn’t have to hear this if there were an alternative. |

|

|

Ethos |

Maybe testimonies from former drivers who use public transit more often would be convincing: “In a survey of PSU students who switched from driving to public transit, 65% said they were not only confident in their choice, but that they were much happier as a result!” |

|

Model Texts by Student Authors

Effective Therapy Through Dance and Movement7

Two chairs, angled slightly away from one another, a small coffee table positioned between them, and an ominous bookshelf behind them, stocked with thick textbooks about psychodynamic theory, Sigmund Freud, and of course, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. This is a psychoanalytic psychotherapist’s typical clinical set-up. Walking into the room, your entire body feels tense—rigid with stress as you enter the therapist’s office only to find the aforementioned sight. Your heartbeat reverberates throughout your body, your throat tightens ever-so-slightly, and your mouth goes dry as an overwhelming sense of nervousness sets in.

Now, imagine instead walking into a beautiful studio, wearing your most comfortable clothing. You take off your shoes, and put your hands in the pockets of your sweatpants as you begin to slip and slide around the sprung hardwood floor whilst a childish smile creeps across your face. Your therapist is not there necessarily to dissect your personality or interpret your behavior, but instead to encourage your mental and physical exploration, leading you on a journey of self-discovery. This is the warm and encouraging environment that dance/movement therapy (DMT) may take place in.

In its essence, DMT is the therapeutic use of physical movement—specifically dance in this context—to encourage and support emotional, intellectual, and motor functions of the mind and body. The focus of the therapy lies within the connection and correlation between movement and emotion (“About”). Unlike so-called “normal” therapies, which are set in a clinical environment, and are conducted by somebody with an extensive background in psychology, DMT is generally practiced by individuals whose background is primarily in dance and the performing arts, with psychology or psychotherapy education falling second. Although some may argue otherwise, I believe that DMT is a viable form of therapy, and that dance and movement can act as the catalyst for profound mental transformation; therefore, when dance and therapy are combined, they create a powerful platform for introspection along with interpersonal discovery, and mental/behavioral change.

Life begins with movement and breathing; they precede all thought and language. Following movement and breath, gesture falls next in the development of personal communication and understanding (Chaiklin 3). Infants and toddlers learn to convey their wants and needs via pointing, yelling, crying, clapping. As adults, we don’t always understand what it is they’re trying to tell us; however, we know that their body language is intended to communicate something important. As a child grows older, a greater emphasis is placed on verbally communicating their wants and needs, and letting go of the physical expression. Furthermore, the childish means of demonstrating wants and needs become socially inappropriate as one matures. Perhaps we should not ignore the impulses to cry, to yell, or to throw a tantrum on the floor, but instead encourage a channeled physical release of pent-up energy.

I personally, would encourage what some would consider as emotional breakdowns within a therapeutic setting. For example, screaming, sobbing, pounding one’s fists against the floor, or kicking a wall all seem taboo in our society, especially when somebody is above the age of three. There is potential for said expressions to become violent and do more harm than good for a client. Therefore, I propose using dance and movement as a method of expressing the same intense emotions.

As a dancer myself, I can personally attest to the benefits of emotional release through movement. I am able to do my best thinking when I am dancing, and immediately after I stop. When dancing, whether it is improvised movement or learned choreography, the body is in both physical and mental motion, as many parts of the brain are activated. The cerebrum is working in overdrive to allow the body to perform certain actions, while other areas of the brain like the cerebellum are trying to match your breathing and oxygen intake to your level of physical exertion. In addition, all parts of the limbic system are triggered. The limbic system is comprised of multiple parts of the brain including the amygdala, hippocampus, thalamus, and hypothalamus. These different areas of the brain are responsible for emotional arousal, certain aspects of memory, and the willingness to be affected by external stimuli. So, when they are activated with movement, they encourage the endocrine system—specifically the pituitary gland—to release hormones that make you feel good about yourself, how you are moving, and allow you to understand what emotions you’re feeling and experiencing (Kinser).

As a form of exercise as well, dancing releases endorphins—proteins that are synthesized by the pituitary gland in response to physiologic stressors. This feeling is so desirable that opioid medications were created with the intent of mimicking the sensation that accompanies an endorphin rush (Sprouse-Blum 70). Along with the beta-proteins comes a level of mental clarity, and a sense of calm. Dance movement therapists should utilize this feeling within therapy, allowing participants to make sense of crises in their life as they exist in this heightened state.

Similar to the potential energy that is explored in physics, when set to music, physical movement manifests a mental state that allows for extensive exploration and introspective discovery. DMT is effective as a therapy in that it allows clients to manifest and confront deep psychological issues while existing in a state of nirvana—the result of dance. Essentially, DMT allows the participant to feel good about him or herself during the sessions, and be open and receptive to learning about their patterns of thought, and any maladaptive behavior (“About”).

Playing specifically to this idea of finding comfort through one’s own body, a case study was done involving an adolescent girl (referred to as “Alex”) who struggled with acute body dysmorphic disorder—a mental illness whose victims are subject to obsession with perceived flaws in their appearance. The aim of the study was to examine “the relationship between an adolescent female’s overall wellness, defined by quality of life, and her participation in a dance/movement therapy [DMT]-based holistic wellness curriculum” (Hagensen 150). During the six-week-long data-collection and observation period, Alex’s sessions took place in a private psychotherapy office and included normal dance and movement based therapy, along with a learning curriculum that focused on mindfulness, body image, movement, friendships, and nutrition. Her therapist wanted not only to ensure that Alex receive the necessary DMT to overcome her body dysmorphic disorder, but also to equip her with the tools to better combat it in the future, should it resurface.

In total, the case study lasted four months, and included nine individual therapy sessions, and a handful of parental check-in meetings (to get their input on her progress). Using the Youth Quality of Life-Research Version (YQOL-R) and parent surveys, both qualitative and quantitative data were collected that revealed that Alex did indeed learn more about herself, and how her body and mind function together. The psychologists involved concluded that the use of DMT was appropriate for Alex’s case, and it proved to be effective in transforming her distorted image of herself (Hagensen 168).

Some may dispute this evidence by saying that the case of a single adolescent girl is not sufficient to deem DMT effective; however, it is extremely difficult to limit confounding variables in large-scale therapeutic experiments. In the realm of psychology, individual studies provide data that is just as important as that of bigger experiments. To further demonstrate DMT’s effectiveness on a larger scale though, I turn to a study that was conducted in Germany in 2012 for evidence.

After recruiting 17 dance therapists and randomly selecting 162 participants, a study was conducted to test the efficacy of a 10-week long DMT group and whether or not the quality of life (QOL) of the participants improved. Ninety-seven of the participants were randomly assigned to the therapy group (the experimental group), whilst the remaining 65 were placed on a waitlist, meaning that they did not receive any treatment (the control group) (Bräuninger 296). All of the participants suffered from stress, and felt that they needed professional help dealing with it. The study utilized a subject-design, and included a pre-test, post-test, and six-month follow-up test. As hypothesized, the results demonstrated that participants in the experimental DMT group significantly improved the QOL, both in the short term (right after the sessions terminated) and in the long term (at the six-month follow-up). The greatest QOL improvements were in the areas of psychological well-being and general life in both the short- and long-term. At the end of the study, it was concluded that, “Dance movement therapy significantly improves QOL in the short and long term” (Bräuninger 301).

DMT does prove to be an effective means of therapy in the cases of body dysmorphic disorder and stress; however, when it comes to using DMT in the treatment of schizophrenia, it seems to fall short. In an attempt to speak to the effectiveness of dance therapy in the context of severe mental illnesses and disorders, a group of psychologists conducted a study to “evaluate the effects of dance therapy for people with schizophrenia or schizophrenia-like illnesses compared with standard care and other interventions” (Xia 675). Although DMT did not do any harm, there was no identifiable reduction in the participant’s symptoms, nor was there an overall improvement in mental cognition. It was concluded that the results of the study did not affirm nor deny the use of dance/movement therapy amongst the group of schizophrenic participants (Xia 676).

I believe that the aforementioned case study brings to light something key about DMT: the kinds of people and mental illnesses that it can be successful for. As demonstrated by the study conducted on schizophrenic patients, DMT isn’t necessarily effective for the entire spectrum of mental illness. DMT has been shown to be more effective for those dealing with less serious mental illnesses, or are simply struggling to cope with passing crises in their life. For example, problems with stress, self-image, family, time management, and relationships are ideal issues to deal with in a DMT setting (Payne 14). Studies have shown that these are the most successfully resolved personal conflicts in this therapy.

Although DMT may not be an effective treatment for certain people or problems, it is unlikely that it will cause detriment to patients, unlike other therapies. For example, it is very common for patients in traditional verbal therapy to feel intense and strong emotions that they were not prepared to encounter, and therefore, not equipped to handle. They can have an increased anxiety and anxiousness as a result of verbal therapy, and even potentially manifest and endure false memories (Linden 308). When a client is difficult to get talking, therapists will inquire for information and ask thought-provoking questions to initiate conversation or better develop their understanding of a patient’s situation. In some cases, this has been shown to encourage the development of false memories because the therapist is overbearing and trying too hard to evoke reactions from their reluctant clients. These negative side effects of therapy may also manifest themselves in DMT; however, this is very unlikely given the holistic nature of the therapy, and the compassionate role of the therapist.

Along with its positive effects on participants, another attribute to the utilization of DMT is that a holistic curriculum may be easily interwoven and incorporated alongside the standard therapy. Instead of participation only in standard therapy sessions, a therapist can also act as a teacher. By helping participants learn about mindfulness and introspection techniques, along with equipping them with coping skills, the therapist/teacher is able to help their clients learn how to combat problems they may face in the future, after therapy has ended. Like in the case of Alex, it is helpful to learn not just about thinking and behavioral patterns, but what they mean, and techniques to keep them in check.

A holistic curriculum is based on “the premise that each person finds identity, meaning, and purpose in life through connections to the community, to the natural world, and to spiritual values such as compassion and peace” (Miller). In other words, when instilled in the context of DMT, participants learn not only about themselves, but also about their interactions with others and the natural world. Although some find such a premise to be too free-spirited for them, the previously mentioned connections are arguably some of the most important one’s in an individual’s life. Many people place too great of an emphasis on being happy, and finding happiness, but choose to ignore the introspective process of examining their relationships. By combining DMT and a holistic curriculum, one can truly begin to understand how they function cognitively, what effect that has on their personal relationships, and what their personal role is in a society and in the world.

Finally, DMT is simply more practical and fun than other, more conventional forms of therapy. It is in essence the vitamin C you would take to not just help you get over a cold, but that you would take to help prevent a cold. In contrast, other therapy styles act as the antibiotics you would take once an infection has set in—there are no preventative measures. When most people make the decision to attend therapy, it is because all else has failed and speaking with a therapist is their last resort. Since DMT is a much more relaxed and natural style of therapy, learned exercise and techniques can easily be incorporated into daily life. While most people won’t keep a journal of their dreams, or record every instance in the day they’ve felt anxious (as many clinical therapists would advise), it would be practical to attend a dance class once a week or so. Just by being in class, learning choreography and allowing the body to move, one can lose and discover themself all at the same time. DMT can be as simple as just improvising movement to a song and allowing the mind to be free for a fleeting moment (Eddy 6). And although short, it can still provide enough time to calm the psyche and encourage distinct moments of introspection.

DMT is an extremely underrated area of psychology. With that being said, I also believe it can be a powerful form of therapy and it has been shown to greatly improve participants’ quality of life and their outlook on it. As demonstrated by the previous case studies and experiments, DMT allows clients to think critically about their own issues and maladaptive behaviors, and become capable of introspection. Although DMT may not be effective for all mental illnesses, it is still nonetheless a powerful tool for significant psychological change, and should be used far more often as a form of treatment. Instead of instantly jumping to the conclusion that traditional psychotherapy is the best option for all clients, patients and therapists alike should perhaps recognize that the most natural thing to our body—movement—could act as the basis for interpersonal discovery and provide impressive levels of mental clarity.

Works Cited

“About Dance/Movement Therapy.” ADTA, American Dance Therapy Association, 2016, https://adta.org/.

Bräuninger, Iris. “The Efficacy of Dance Movement Therapy Group on Improvement of Quality of Life: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” The Arts in Psychotherapy, vol. 39, no. 4, 2012, pp. 296-303. Elsevier ScienceDirect, doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2012.03.008.

Chaiklin, Sharon, and Hilda Wengrower. Art and Science of Dance/Movement Therapy: Life Is Dance, Routledge, 2009. ProQuest eBook Library, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com.proxy.lib.pdx.edu/lib/psu/detail.action?docID=668472.

Eddy, Martha. “A Brief History of Somatic Practices and Dance: Historical Development of the Field of Somatic Education and Its Relationship to Dance.” Journal of Dance & Somatic Practices, vol. 1, no. 1, 2009, pp. 5-27. IngentaConnect, doi: 10.1386/jdsp.1.1.5/1.

Hagensen, Kendall. “Using a Dance/Movement Therapy-Based Wellness Curriculum: An Adolescent Case Study.” American Journal of Dance Therapy, vol. 37, no. 2, 2015, pp. 150-175. SpringerLink, doi: 10.1007/s10465-015-9199-4.

Kinser, Patricia Anne. “Brain Structures and Their Functions.” Serendip Studio, Bryn Mawr, 5 Sept 2012, http://serendip.brynmawr.edu/bb/kinser/Structure1.html.

Linden, Michael, and Marie-Luise Schermuly-Haupt. “Definition, Assessment and Rate of Psychotherapy Side Effects.” World Psychiatry, vol. 13, no. 3, 2014, pp. 306-309. US National Library of Medicine, doi: 10.1002/wps.20153.

Meekums, Bonnie. Dance Movement Therapy: A Creative Psychotherapeutic Approach, SAGE, 2002. ProQuest eBook Library, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com.proxy.lib.pdx.edu/lib/psu/detail.action?docID=668472.

Miller, Ron. “A Brief Introduction to Holistic Education.” infed, YMCA George Williams College, March 2000, http://infed.org/mobi/a-brief-introduction-to-holistic-education/.

Payne, Helen. Dance Movement Therapy: Theory and Practice, Tavistock/Routledge, 1992. ProQuest eBook Library, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com.proxy.lib.pdx.edu/lib/psu/detail.action?docID=668472.

Sprouse-Blum, Adam, Greg Smith, Daniel Sugai, and Don Parsa. “Understanding Endorphins and Their Importance in Pain Management.” Hawaii Medical Journal, vol. 69, no. 3, 2010, pp. 70-71. US National Library of Medicine, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3104618/.

Xia, Jun, and Tessa Jan Grant. “Dance Therapy for People With Schizophrenia.” Schizophrenia Bulletin, vol. 35, no. 4, 2009, pp. 675-76. Oxford Journals. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp042.

We Don’t Care About Child Slaves8

When you walk into the mall or any department store, your main goal is to snatch a deal, right? You scout for the prettiest dress with the lowest price or the best fitting jeans with the biggest discount. And once you find it, you go to the checkout and purchase it right away. Congratulations—now it’s all yours! But here’s the thing: the item that you just purchased could have possibly been made from the sweat, blood, and tears of a six-year-old child in Vietnam. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), one in ten Vietnamese children aged 5 to 17 are slave workers, and Vietnam is the second biggest source of imported goods to the US. This means that a lot of the things we get from Target, Walmart, and countless other stores are made by child slaves. The problem is that the bargain on that cute shirt we just got was too good for us to think twice—about where it came from, how it was made. As a society, we need to take action against child labor by being conscious of where we buy our goods so we don’t feed the system that exploits children.

When we think of child slavery, we are horrified by it. How can someone treat children in such a way? It’s horrific, it’s terrible, and it’s a serious crime! But then again, those shoes you saw in the store are so cute and are at such a cheap price, you must buy them! Even if they were made by child slaves, you can’t do anything about that situation and purchasing them won’t do any harm at all, right? The unfortunate reality is that we are all hypocritical when it comes to this issue. I’m pretty sure that all of us have some sort of knowledge of child slave workers in third-world countries, but how come we never take it into consideration when we buy stuff? Maybe it’s because you believe your actions as one person are too little to affect anything, or you just can’t pass up that deal. Either way, we need to all start doing research about where we are sending our money.

As of 2014, 1.75 million Vietnamese children are working in conditions that are classified as child labor according to the ILO (Rau). Most of these children work in crowded factories and work more than 42 hours a week. These children are the ones who make your clothes, toys, and other knick-knacks that you get from Target, Walmart, etc. If not that, they’re the ones who make the zippers on your coats and buttons on your sweater in a horrifying, physically unstable work environment.

How exactly do these children end up in this situation? According to a BBC report, labor traffickers specifically target children in remote and poor villages, offering to take them to the city to teach them vocational training or technical skills. Their parents usually agree because they are not aware of the concept of human trafficking since they live in an isolated area. Also, it gives the family an extra source of income. The children are then sent to other places and are forced to work in mostly farms or factories. These children receive little to no pay and most of the time get beaten if they made a mistake while working. They are also subject to mental abuse and at the worst, physically tortured by their boss. Another reason why children end up in the labor force is because they must provide for their family; their parents are unable to do so for whatever reason (Brown).

In 2013, BBC uncovered the story of a Vietnamese child labor victim identified as “Hieu.” Hieu was a slave worker in Ho Chi Minh city who jumped out of the third floor window of a factory with two other boys to escape his “workplace.” Aged 16 at the time, Hieu explained that a woman approached him in his rural village in Dien Bien, the country’s poorest province, and offered him vocational training in the city. He and 11 other children were then sent to the city and forced to make clothes for a garment factory in a cramped room for the next two years. “We started at 6AM and finished work at midnight,” he said. “If we made a mistake making the clothes they would beat us with a stick.” Fortunately for Hieu, he managed to escape and is one of the 230 children saved by The Blue Dragon Foundation, a charity that helps fight against child labor (Brown).

For the rest of the victims, however, hope is yet to be found. According to the US Department of Commerce, most of the apparel that is sold in the US is made overseas, and Vietnam is the second biggest source for imported goods right behind China. Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Sri Lanka are also on the list of the top sources of US apparel imports. This means that the demand for goods from these countries is high; therefore, the need for child slave workers is increasing.

One of the biggest corporations in the world that has an ongoing history of the use of child slaves is Nike. According to IHSCS News, workers at Vietnam shoe manufacturing plants make 20 cents an hour, are beaten by supervisors, and are not allowed to leave their work posts. Vietnam isn’t the only place that has factories with dangerous working conditions owned by the athletic-wear giant (Wilsey). Nike also has sweatshops in Bangladesh, Pakistan, Indonesia, and China, just to name a few, that have all been investigated by officials due to inhumane working conditions. Everything from clothing and shoes, to soccer balls are potentially made by child slaves in these countries (Greenhouse). Please keep this in mind the next time you visit your local Nike store.

Vietnam has actually been praised for its efforts in combating child slave issues. According to The Borgen Project, Vietnam has increased the number of prosecutions it holds to help end overseas gang activity (Rau). However, the country lacks internal control in child trafficking, and traffickers who are caught receive light punishments. The person who trafficked Hieu and the 11 other children only faced a fine of $500 and his factory was closed down, but he did not go to court (Brown).

Let’s be real: doing our part to fight against child labor as members of a capitalistic society is not the easiest thing to do. We are all humans who have needs and our constant demand to buy is hard to resist, especially when our society is fueled by consumerism. However, big changes takes little steps. We can start to combat this issue by doing research on where we spend our money and try to not support corporations and companies that will enable the child labor system. We can also donate to charities, such as The Blue Dragon Foundation, to further help the cause. Yes, it is hard to not shop at your favorite stores and I can’t stop you from doing so. But all I ask is that you educate yourself on where you are spending your money, and hopefully your moral compass will guide you onto the right path. If you are horrified by the thought of a 5-year-old child being beaten and working 24 hours a day, do not be a part of the problem. Keep Hieu—and the other 1.75 million children who are currently suffering in Vietnam—in mind the next time you buy something.

Works Cited

Brown, Marianne. “Vietnam’s Lost Children in Labyrinth of Slave Labour.” BBC News, 27 Aug 2013, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-23631923.

Greenhouse, Steven. “Nike Shoe Plant in Vietnam Is Called Unsafe for Workers.” The New York Times, 7 Nov 1997, http://www.nytimes.com/1997/11/08/business/nike-shoe-plant-in-vietnam-is-called-unsafe-for-workers.html.

Nguyen Thị Lan Huong, et al. Viet Nam National Child Labour Survey 2012. International Labour Organization, 14 Mar 2014, http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—asia/—ro-bangkok/—ilo-hanoi/documents/publication/wcms_237833.pdf.

“One in Ten Vietnamese Youngsters Aged 5-17 in Child Labour.” International Labour Organization, 14 Mar 2014, http://www.ilo.org/hanoi/Informationresources/Publicinformation/newsitems/WCMS_237788/lang–en/index.htm.

Rau, Ashrita. “Child Labor in Vietnam.” The Borgen Project, 20 Mar 2017, https://borgenproject.org/child-labor-vietnam/.

Wilsey, Matt, and Scott Lichtig. “The Nike Controversy.” EDGE Course Seminar Website, Stanford University, 27 July 1999, https://web.stanford.edu/class/e297c/trade_environment/wheeling/hnike.html.

Carnivore Consumption Killing Climate9

The year of 1955 was the year of many revolutionary names: you might remember the rise of Elvis or the valor of Rosa Parks that year. Some might recognize it as the birth year of two of the 20th centuries best and brightest: Mr. Jobs, and Mr. Gates. However, I recognize it as the birth year of a pair even brighter than that of Steve and Bill. A pair of golden arches that is: McDonald’s was founded April 15, 1955, and ever since then, the market for fast, greasy, and cheap food has been a staple in many countries around the world. Which has led to a steady rise in the consumption of meat and other animal products. This spells out disaster for not only personal health but the health of the environment. The direct link between the consumption of animal products and global warming is negatively effecting the health of this generation. If action isn’t taken by each of us, global warming will be hazardous for future generations who will be left with the burden of reversing the wastefulness of their greedy ancestors.

While there are many industries that contribute to global warming, the food and farming industry has one of the largest impacts on the environment. For starters, every step of the process, from the birth of the calf to the burger patty sizzling on the grill, produces near irreversible damage to the environment. All livestock, not only cows, passively contribute to global warming. “Livestock, especially cattle, produce methane (CH4) as part of their digestion. This process is called enteric fermentation, and it represents almost one third of the emissions from the Agriculture sector” (“Greenhouse”). While this may seem insignificant to nice small farms with only a few cows, large corporations own thousands of cattle, all of which add up to significant amount of enteric fermentation. Not to mention, the thousands of gallons of gas that goes into transporting the cows and there are tons of coal or fossil fuels being burned to power big warehouses where cows and other various meat-producing animals are crammed into undersized cages, where they are modified and bred for slaughter.

Moreover, the driving of semis release carbon dioxide into the air. These trucks are used to haul the animals, their feed, and the final product, your food. The final number of trips, when all said and done, adds up to an enormous amount of gas being burned. “When we burn fossil fuels, such as coal and gas, we release carbon dioxide (CO2). CO2 builds up in the atmosphere and causes Earth’s temperature to rise” (“Climate”). In summary, the burning of gas and other fossil fuels in one major way the meat, and the entire food industry contributes to global warming. The rising of the earth’s temperature is like the flick of the first domino in the line. Heating of the Earth being the first domino leading to melting the ice caps and so on. Everyone has heard the spiel of melting ice caps and “saving the polar bears!”; however, there are many serious and harmful effects of such CO2 emissions. Some may rebuttal that “global warming doesn’t have any effect on me”, but there is a list of health problems caused by global warming that do negatively impact humans.

Unless people can come together and reduce, not just their CO2 footprint, but all greenhouse gas emissions there will continue to be an increase medical problems globally. The rising temperatures is causing longer allergy seasons and an increase in allergens or dust, pollen and other particles in the air. “Research studies associate fine particles [allergens] with negative cardiovascular outcomes such as heart attacks, formation of deep vein blood clots, and increased mortality from several other causes. These adverse health impacts intensify as temperatures rise” (Portier 14). For further explanation, polluting the atmosphere by burning gas and raising mass numbers of livestock is causing the global temperature to rise. These negative health issues are only the outcome of global warming. I have purposely omitted the health problems, though many, of eating red meat. Cutting meat out of your diet will improve your individual health, but more importantly, it will improve the health of the earth. Some critics might argue that eating just one burger can’t raise the entire Earth’s temperature. The simple answer is, it doesn’t. However, making the conscious decision to eat meat on a day to day basis adds up to a slew of health problems accompanied by a large personal carbon footprint.

Acidification of the oceans is one of the harmful effects on the environment caused by an inflated carbon footprint. This happens when the CO2 that is released into the atmosphere, absorbs into the ocean, thus leading to a change in the pH level of the ocean. “High concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere increase the amount that is dissolved into the ocean, leading to acidification… many [people on coastal regions] depend on marine protein for daily subsistence, the consequences of perturbing delicate ocean and coastal systems will be far-reaching” (Portier 6). This is problematic for any who live on coastal regions and may rely heavily on seafood in their diet but is also a problem for the fish as well. Disrupting an entire food chain could have many unforeseen consequences.

Meat lovers will interject: “well food other than meat is produced in factories, don’t those contribute to global warming too?” These arguments are not invalid; while the meat industry may cause much of the food and agriculture’s emissions, other methods of food production are outdated and harmful as well. The problem of global warming, is not solely the fault of the meat industry, the blame should be put onto anyone who produces more than their fair share of greenhouse gases. For example, the way rice is cultivated could very well be a place CO2 emissions could be cut. “A change in rice processing and consumption patterns could reduce CO2 emission by 2-16%” (Norton 42). The implementation made to reduce the footprint of rice cultivation, could then be remodeled to be effectively used to reduce the pollution of the food and agriculture sector as a whole.

However, more simple things than changing the way food is produced can help save the environment. It can be as simple as picking up a piece of litter off the ground to deciding to recycle all your bottles and cans. But for those looking to make a greater contribution to saving the world, stop eating meat. Or, if that is too difficult, reduce the amount of meat you eat. A paper published by the World Resources Institute “showed that reducing heavy red meat consumption, would lead to a per capita food and land use-related greenhouse gas emissions reduction of between 15 and 35 percent by 2050. Going vegetarian could reduce those per capita emissions by half” (Magill). As a vegetarian I gave up eating meat mainly for this reason. But not only can you save the environment by giving up meat, by doing so you can save more than just your life, but millions of lives; “switching to vegetarianism could help prevent nearly 7m premature deaths and help reduce health care costs by $1b” (Harvey). As mentioned, there are multiple positive impacts of eliminating meat from your diet, and it is the best way to reduce your carbon footprint. In tandem, being aware of your carbon footprint is very important, because not monitoring individual emissions is causing greenhouse gases to reach dangerous levels. Which is beginning to cause a variety of health problems for many people which will only intensify if nothing is done on a personal and global level.

Not only do we have to worry about the changes to ocean and costal life, but life everywhere will get far worse if nothing is done to stop the warming of our planet. A world dominated by scientifically advanced greedy carnivores is not a world worth saving. The earth is on a slippery slope that is leading to extinction. The way we consume animal products is irresponsible because it poses a major threat to the environment and endangers humans. To respond to this, we need to develop new ways to combat ecological problems and change wasteful consumption habits. If we cannot stop our polluting and wasteful ways, we are destined to lose the planet that harbors everything we know.

To change the eating habits of an entire nation might be a feat all its own; changing the eating habits of an entire world seems impossible. I am confident that it all starts with one person making the right choice. I urge you to follow not only in my footsteps, but join the millions of others who are putting down their steak knives to fight climate change. I find it horrifying that some people would rather destroy their own race than change what goes on their plate. There is overwhelming evidence that illuminates the fiery connection between global warming and serious health problems. Now this generation and future generations will need to create regulations and invent new solutions to enjoy the same planet we have all called home.

Teacher Takeaways

“This essay is a good example of an Aristotelian argument; the author clearly presents their stance and their desired purpose, supporting both with a blend of logos, pathos, and ethos. It’s clear that the author is passionate and knowledgeable. I would say as a meat-eater, though, that many readers would feel attacked by some of the rhetorical figures included here: no one wants to be part of the group of ‘scientifically advanced greedy carnivores’ that will make our world uninhabitable, regardless of the truth of that statement. Additionally, the author seems to lose track of their thesis throughout paragraphs four and five. I would encourage them to make sure every paragraph begins and ends with a connection to the thesis statement.”– Professor Dawson

Works Cited

Adams, Jill. “Can U.S., Nations Meet Emission Goals?” CQ Researcher, 15 June 2016.

“Climate Change Decreases the Quality of Air We Breathe.” Center of Disease Control and American Public Health Association, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 18 April 2016.

“Climate Change: How Do We Know?” National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Earth Science Communications Team at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 18 June 2018.

Doyle, Julie, Michael Redclift, and Graham Woodgate. Meditating Climate Change, Routledge, August 2011.

“Greenhouse Gas Emissions.” U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 11 April 2018.

Harvey, Fiona. “Eat Less Meat to Avoid Global Warming Scientists Say.” The Guardian, 21 March, 2016.

“Human Induced Climate Change Requires Immediate Action.” American Geophysical Union, August 2013.

Magill, Bobby. “Studies Show Link Between Red-Meat and Climate Change.” Climate Central, 20 April 2016.

Norton, Tomas, Brijesh K. Tiwari, and Nicholas M. Holden. Sustainable Food Processing, Wiley-Blackwell, 2014. Wiley Online Library, doi: 10.1002/9781118634301.

Portier, Christopher J., et al. A Human Health Perspective on Climate Change. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 22 April 2010.

Endotes

a rhetorical mode in which different perspectives on a common issue are negotiated. See Aristotelian and Rogerian arguments.

a mode of argument by which a writer attempts to convince their audience that one perspective is accurate.

the intended consumers for a piece of rhetoric. Every text has at least one audience; sometimes, that audience is directly addressed, and other times we have to infer.

a persuasive writer’s directive to their audience; usually located toward the end of a text. Compare with purpose.

a rhetorical appeal based on authority, credibility, or expertise.

the setting (time and place) or atmosphere in which an argument is actionable or ideal. Consider alongside “occasion.”

a line of logical reasoning which follows a pattern of that makes an error in its basic structure. For example, Kanye West is on TV; Animal Planet is on TV. Therefore, Kanye West is on Animal Planet.

a rhetorical appeal to logical reasoning.

a neologism from ‘impartial,’ refers to occupying and appreciating a variety of perspectives rather than pretending to have no perspective. Rather than unbiased or neutral, multipartial writers are balanced, acknowledging and respecting many different ideas.

a rhetorical appeal to emotion.

a means by which a writer or speaker connects with their audience to achieve their purpose. Most commonly refers to logos, pathos, and ethos.

a mode of argument by which an author seeks compromise by bringing different perspectives on an issue into conversation. Acknowledges that no one perspective is absolutely and exclusively ‘right’; values disagreement in order to make moral, political, and practical decisions.

a line of logical reasoning similar to the transitive property (If a=b and b=c, then a=c). For example, All humans need oxygen; Kanye West is a human. Therefore, Kanye West needs oxygen.