Chapter Nine: Interacting with Sources

Less than one generation ago, the biggest challenge facing research writers like you was tracking down relevant, credible, and useful information. Even the most basic projects required sifting through card catalogues, scrolling through endless microfiche and microfilm slides, and dedicating hours to scouring the stacks of different libraries. But now, there is no dearth of information: indeed, the Internet has connected us to more information than any single person could process in an entire lifetime.

Once you have determined which conversation you want to join, it’s time to begin finding sources. Inquiry-based research requires many encounters with a diversity of sources, so the Internet serves us well by enabling faster, more expansive access. But while the Internet makes it much easier to find those sources, it comes with its own host of challenges. The biggest problems with primarily Internet-based research can be boiled down to two issues:

- There is too much out there to sift through everything that might be relevant, and

- There is an increased prominence of unreliable, biased, or simply untrue information.

This chapter focuses on developing strategies and techniques to make your research and research writing processes more efficient, reliable, and meaningful, especially when considering the unique difficulties presented by research writing in the digital age. Specifically, you will learn strategies for discovering, evaluating, and integrating sources.

Chapter Vocabulary

Vocabulary |

Definition |

|

a research tool that organizes citations with a brief paragraph for each source examined. |

|

|

a posture from which to read; reader makes efforts to appreciate, understand, and agree with the text they encounter. |

|

|

a direct quote of more than four lines which is reformatted according to stylistic guidelines. |

|

|

the process of finding new sources using hyperlinked subject tags in the search results of a database. |

|

|

the process of using a text’s citations, bibliography, or notes to track down other similar or related sources. |

|

|

an argument determining relative value (i.e., better, best, worse, worst). Requires informed judgment based on evidence and a consistent metric. |

|

|

an argument exploring a measurable but arguable happening. Typically more straightforward than other claims, but should still be arguable and worth discussion. |

|

|

an argument that proposes a plan of action to address an issue. Articulates a stance that requires action, often informed by understanding of both phenomenon and evaluation. Often uses the word “should.” See call-to-action. |

|

|

a technique for evaluating the credibility and use-value of a source; researcher considers the Currency, Relevance, Accuracy, Authority, and Purpose of the source to determine if it is trustworthy and useful. |

|

|

the degree to which a text—its content, its author, and/or its publisher—is trustworthy and accurate. |

|

|

the verbatim use of another author’s words. Can be used as evidence to support your claim, or as language to analyze/close-read to demonstrate an interpretation or insight. |

|

|

a posture from which to read; reader makes efforts to challenge, critique, or undermine the text they encounter. |

|

|

a part or combination of parts that lends support or proof to an arguable topic, idea, or interpretation. |

|

|

a voice that disagrees with the writer or speaker included within the text itself. Can be literal or imaginary. Helps author respond to criticism, transition between ideas, and manage argumentation. |

|

|

author reiterates a main idea, argument, or detail of a text in their own words without drastically altering the length of the passage(s) they paraphrase. Contrast with summary. |

|

|

a psychological effect experienced by most audiences: the opening statements of a text are more memorable than much of the content because they leave a ‘first impression’ in the audience’s memory. Contrast with recency effect. |

|

|

a psychological effect experienced by most audiences: the concluding statements of a text are more memorable than much of the content because they are more recent in the audience’s memory. Contrast with primacy effect. |

|

|

a phrase or sentence that directs your reader. It can help you make connections, guide your reader’s interpretation, ease transitions, and re-orient you to your thesis. Also known as a “signal phrase.” |

|

|

a rhetorical mode in which an author reiterates the main ideas, arguments, and details of a text in their own words, condensing a longer text into a smaller version. Contrast with paraphrase. |

|

|

a 1-3 sentence statement outlining the main insight(s), argument(s), or concern(s) of an essay; not necessary in every rhetorical situation; typically found at the beginning of an essay, though sometimes embedded later in the paper. Also referred to as a “So what?” statement. |

|

|

the degree to which a text is usable for your specific project. A source is not inherently good or bad, but rather useful or not useful. Use-value is influenced by many factors, including credibility. See credibility and CRAAP Test. |

|

Techniques

Research Methods: Discovering Sources

Let’s bust a myth before going any further: there is no such thing as a “good” source. Check out this video from Portland Community College.

What makes a source “good” is actually determined by your purpose: how you use the source in your text is most important to determining its value. If you plan to present something as truth—like a fact or statistic—it is wise to use a peer-reviewed journal article (one that has been evaluated by a community of scholars). But if you’re trying to demonstrate a perspective or give evidence, you may not find what you need in a journal.

|

Your Position |

A Supporting Fact (Something you present as factual) |

An Example that Demonstrates Your Position (Something that you present as a perspective) |

|

Women are unfairly criticized on social media. |

A peer-reviewed scholarly article: |

A popular but clickbait-y news site: Tamplin, Harley. “Instagram Users Are Massive Narcissists, Study Shows.” Elite Daily, Bustle Digital Group3 April 2017. |

If you want to showcase a diversity of perspectives, you will want to weave together a diversity of sources.

As you discover useful sources, try to expand your usual research process by experimenting with the techniques and resources included in this chapter.

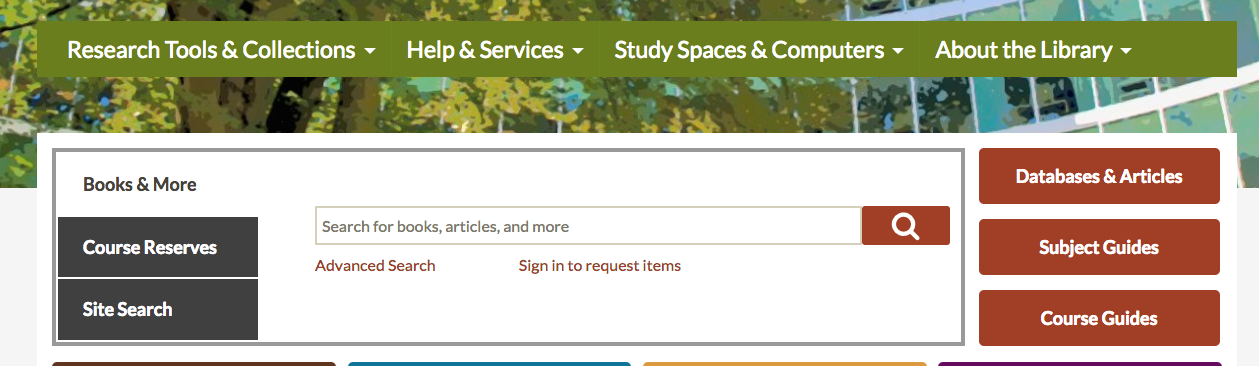

The first and most important determining factor of your research is where you choose to begin. Although there are a great number of credible and useful texts available across different search platforms, I generally encourage my students begin with two resources:

Their college or university’s library and its website, and

Google Scholar.

These resources are not bulletproof, and you can’t always find what you need through them. However, their general search functionality and the databases from which they draw tend to be more reliable, specific, and professional. It is quite likely that your argument will be better received if it relies on the kind of sources you discover with these tools.

Your Library

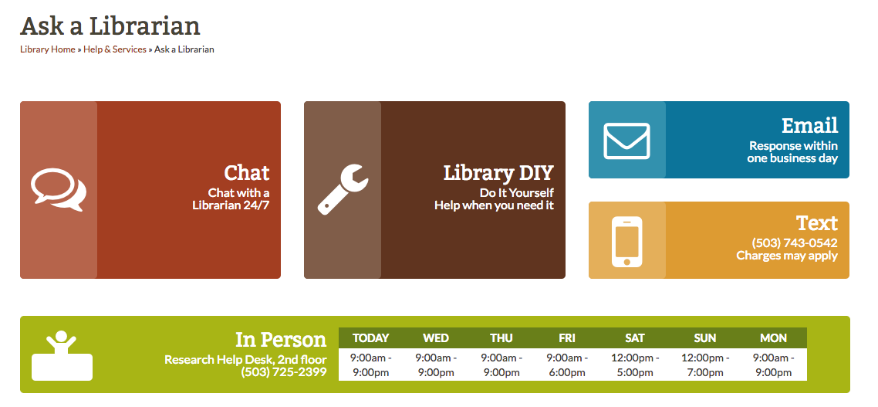

Although the following information primarily focuses on making good use of your library’s online tools, one of the most valuable and under-utilized resources at your disposal are the librarians themselves. Do you know if your school has research librarians on staff? How about your local library? Research librarians (or, reference librarians) are not only well-versed in the research process, but they are also passionate about supporting students in their inquiry.

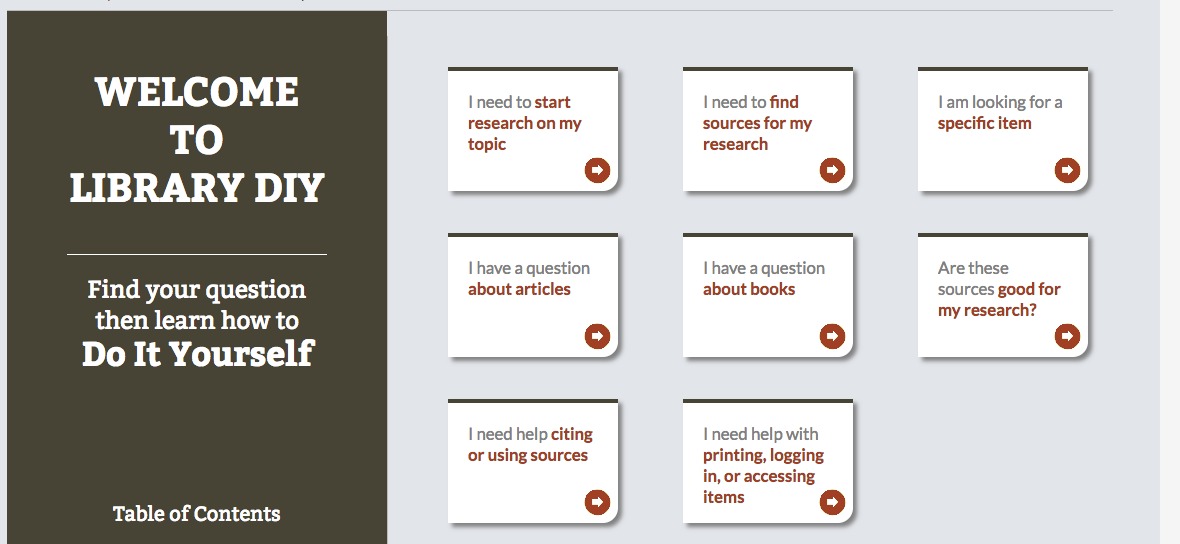

It’s also possible that your library offers research support that you can access remotely: many colleges and universities provide librarian support via phone, text, instant message/chat, or e-mail. Some libraries even make video tutorials and do-it-yourself research tips and tricks.

The first step in learning how your library will support you is to investigate their website. Although I can’t provide specific instruction for the use of your library website—they are all slightly different—I encourage you to spend ten minutes familiarizing yourself with the site, considering the following questions especially:

- Does the site have an FAQ, student support, Librarian Chat, or DIY link in case you have questions?

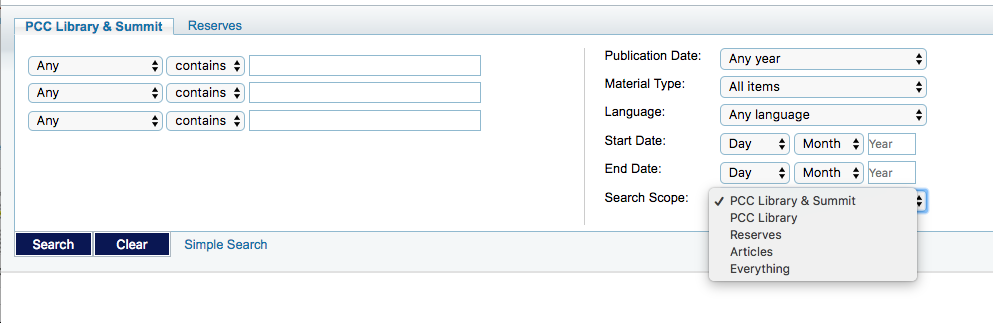

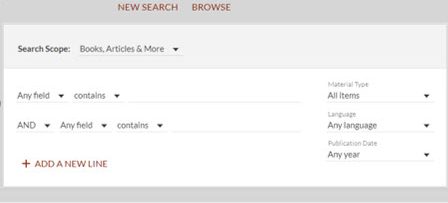

- Does the site have an integrated search bar (i.e., a search engine that allows you to search some or all databases and the library catalogue simultaneously)?

- How do you access the “advanced search” function of the library’s search bar?

- Does your account have an eShelf or reading list to save sources you find?

- Is your library a member of a resource sharing network, like ILLiad or SUMMIT? How do you request a source through this network?

- Does your library subscribe to multimedia or digital resource services, like video streaming or eBook libraries?

- Does the site offer any citation management support software, like Mendeley or Zotero? (You can find links to these tools in the Additional Recommended Resources appendix.)

Depending on where you’re learning, your school will provide different access to scholarly articles, books, and other media.

Most schools pay subscriptions to databases filled will academic works in addition to owning a body of physical texts (books, DVDs, magazines, etc.). Some schools are members of exchange services for physical texts as well, in which case a network of libraries can provide resources to students at your school.

It is worth noting that most library websites use an older form of search technology. You have likely realized that day-to-day search engines like Google will predict what you’re searching, correct your spelling, and automatically return results that your search terms might not have exactly aligned with. (For example, I could google How many basketball players on Jazz roster and I would still likely get the results I needed.) Most library search engines don’t do this, so you need to be very deliberate with your search terms. Here are some tips:

- Consider synonyms and jargon that might be more likely to yield results. As you research, you will become more fluent in the language of your subject. Keep track of vocabulary that other scholars use, and revise your search terms based on this context-specific language.

- Use the Boolean operators ? and * for expanded results:

- wom?n yields results for woman, women, womyn, etc.

- medic* yields results for medic, medicine, medication, medicinal, medical, etc.

- Use the advanced search feature to combine search terms, exclude certain results, limit the search terms’ applicability, etc.

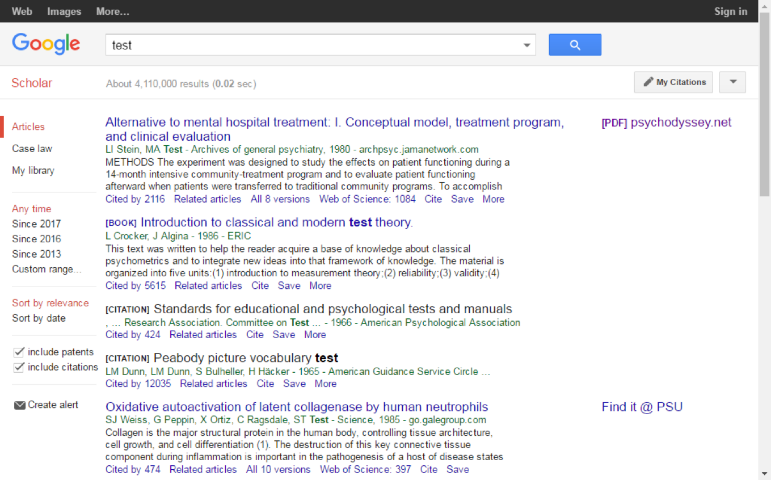

Google Scholar

Because Google Scholar is a bit more intuitive than most library search engines, and because it draws from large databases, you might find it easier to use. Many of the results you turn up using Google Scholar are available online as free access PDFs.

That said, Scholar will often bring up citations for books, articles, and other texts that you don’t have access to. Before you use Google Scholar, make sure you’re logged in to your school account in the same browser; the search engine should provide links to “Find it @ [your school]” if your institution subscribes to the appropriate database.

If you find a citation, article preview, or other text via Google Scholar but can’t access it easily, you return to your library website and search for it directly. It’s possible that you have access to the text via a loaning program like ILLiad.

Google Scholar will also let you limit your results by various constraints, making it easier to wade through many, many results.

- Google Tricks That Will Change the Way You Search” by Jack Linshi

- “Refine web searches” and “Filter your search results” from Google’s help section

Wikipedia

A quick note on Wikipedia: many instructors forbid the use of Wikipedia as a cited source in an essay. Wikipedia is a great place for quick facts and background knowledge, but because its content is user-created and -curated, it is vulnerable to the spread of misinformation characteristic of the broader Internet. Wikipedia has been vetting their articles more thoroughly in recent years, but only about 1 in 200 are internally rated as “good articles.” There are two hacks that you should know in order to use Wikipedia more critically:

- It is wise to avoid a page has a warning banner at the top, such as:

- This article needs to be updated,

- The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject,

- The neutrality of this article is disputed,

- This article needs additional citations for verification,

- This article includes a list of references, but its sources remain unclear because it has insufficient inline citations.

- If your Wikipedia information is crucial and seems reliable, use the linked citation to draw from instead of the Wikipedia page, as pictured below. This will help you ensure that the linked content is legitimate (dead links and suspect citations are no good) and avoid citing Wikipedia as a main source.

Other Resources

As we will continue to discuss, the most useful sources for your research project are not always proper academic, peer-reviewed articles. For instance, if I were writing a paper on the experience of working for United Airlines, a compelling blog post by a flight attendant that speaks to the actual working conditions they experienced might be more appropriate than a data-driven scholarly investigation of the United Airlines consumer trends. You might find that a TED Talk, a published interview, an advertisement, or some other non-academic source would be useful for your writing. Therefore, it’s important that you apply the skills and techniques from “Evaluating Sources” to all the texts you encounter, being especially careful with texts that some people might see as unreliable.

Additional Techniques for Discovering Sources

All it takes is one or two really good sources to get you started. You should keep your perspective wide to catch as much as you can—but if you’ve found a handful of good sources, there are four tools that can help you find even more:

The author of that perfect article probably got some of their information from somewhere else, just like you. Citation mining is the

process of using a text’s citations, bibliography, or notes to track down other similar or related sources. Plug the author’s citations into your school’s library search engine or Google Scholar to see if you have access.

Web of Science is like reverse citation mining: instead of using a text’s bibliography to find more sources, you find other sources that cite your text in their bibliographies. Web of Science is a digital archive that shows you connections between different authors and their writing—and not only for science! If you find a good source that is documented in this database, you can see other texts that cite that source.

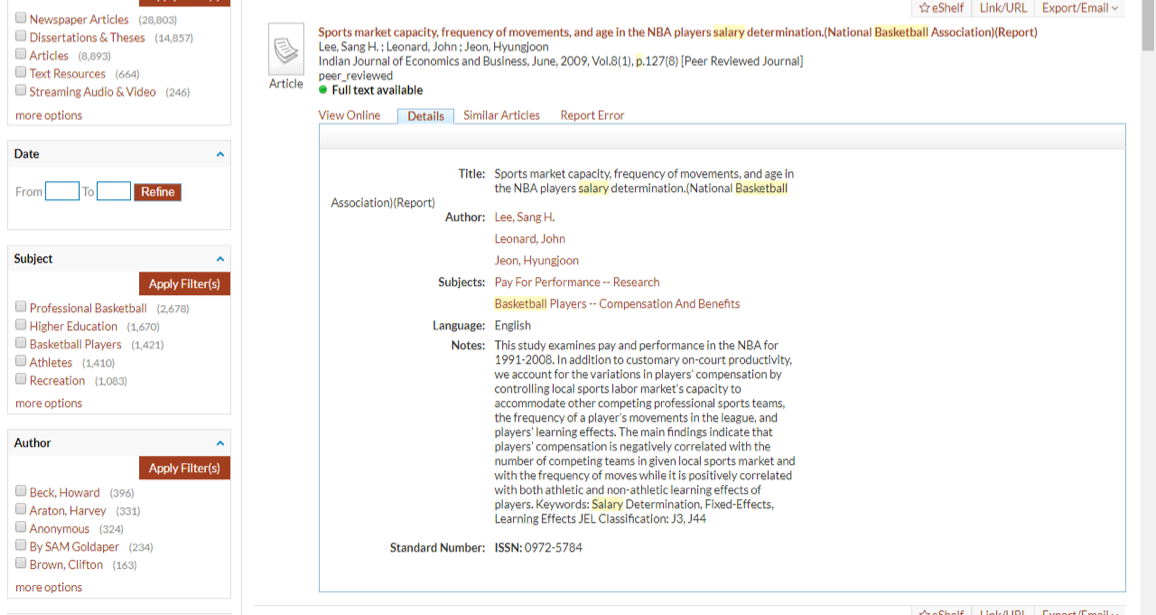

Bootstrapping is a technique that works best on search engines with detail features, like your library search engine. As you can see in the screenshot below, these search engines tag each text with certain subject keywords. By clicking on those keywords, you can link to other texts tagged with the same keywords, typically according to Library of Congress standards.

- WorldCat is a tremendous tool that catalogs the most citations of any database I’ve ever seen. Even though you can’t always access texts through WorldCat, you can figure out which nearby libraries might be able to help you out.

The first and most important piece of advice I can offer you as you begin to dig into these sources: stay organized. By taking notes and keeping record of where each idea is coming from, you save yourself a lot of time—and avoid the risk of unintentional plagiarism. If you could stand to brush up on your notetaking skills, take a look at Appendix A: Engaged Reading Strategies.

Research Methods: Evaluating Sources

If there’s no such thing as an inherently “good” or “bad” source, how do we determine if a source is right for our purposes? As you sift through sources, you should consider credibility and use-value to determine whether a source is right for you. Credibility refers to the reliability and accuracy of the author, their writing, and the publisher. Use-value is a broad term that includes whether you should use a text in your research paper, as well as how you will use that text. The CRAAP Test will help you explore both credibility and use-value.

|

Currency |

How recently was the text created? Does that impact the accuracy or value of its contents, either positively or negatively? |

|

|

Generally, a text that is current is more credible and useful: data will be more accurate, the content will reflect more up-to-date ideas, and so on. However, there are some exceptions.

|

|

Relevance |

Is the text closely related to your topic? Does it illuminate your topic, or is it only tangentially connected? |

|

|

A text that is relevant is generally more useful, as you probably already realize. Exceptions to this might include:

|

|

Accuracy |

Is there any reason to doubt the validity of the text? Is it possible that the information and ideas included are simply untrue? |

|

|

You might start out by relying on your instincts to answer these questions, but your evaluation of accuracy should also informed more objectively by the other elements of the CRAAP Test (e.g., if a text is outdated, it might no longer be accurate). Of course, the importance of this element depends on your use of the source; for instance, if I were writing a paper on conservative responses to Planned Parenthood, I might find it useful to discuss the inaccurate videos released by a pro-choice group several years ago. |

|

Authority |

Who is the author? Who is the publisher? Do either or both demonstrate ethos through their experience, credentials, or public perception? |

|

|

This element also depends on your use of the source; for instance, if I were writing a paper on cyberbullying, I might find it useful to bring in posts from anonymous teenagers. Often, though, academic presses (e.g., Oxford University) and government publishers (e.g., hhs.gov) are assumed to have an increased degree of authority when compared with popular presses (e.g., The Atlantic) or self-published texts (e.g., blogs). It may be difficult to ascertain an author and a publisher’s authority without further research, but here are some red flags if you’re evaluating a source with questionable authority:

|

|

Purpose |

What is the author trying to achieve with their text? What are their motivations or reasons for publication and writing? Does that purpose influence the credibility of the text? |

|

|

As we’ve discussed, every piece of rhetoric has a purpose. It’s important that you identify and evaluate the implied and/or declared purposes of a text before you put too much faith in it. |

Even though you’re making efforts to keep an open mind to different positions, it is likely that you’ve already formed some opinions about your topic. As you review each source, try to read both with and against the grain; in other words, try to position yourself at least once as a doubter and at least once as believer. Regardless of what the source actually has to say, you should (a) try to take the argument on its own terms and try to appreciate or understand it; and (b) be critical of it, looking for its blind spots and problems. This is especially important when we encounter texts we really like or really dislike—we need to challenge our early perceptions to interrupt projection.

As you proceed through each step of the CRAAP Test, try to come up with answers as both a doubter and a believer. For example, try to come up with a reason why a source’s Authority makes it credible and useful; then, come up with a reason why the same source’s Authority makes it unreliable and not useful.

This may seem like a cumbersome process, but with enough practice, the CRAAP Test will become second nature. You will become more efficient as you evaluate more texts, and eventually you will be able to identify a source’s use-value and credibility without running the entire test. Furthermore, as you may already realize, you can eventually just start eliminating sources if they fail to demonstrate credibility and/or use-value through at least one step of the CRAAP Test.

Interpreting Sources and Processing Information

Once you’ve found a source that seems both useful and credible, you should spend some time reading, rereading, and interpreting that text. The more time you allow yourself to think through a text, the more likely your use of it will be rhetorically effective.

Although it is time-consuming, I encourage you to process each text by:

- Reading once through, trying to develop a global understanding of the content

- Re-reading at least once, annotating the text along the way, and then copying quotes, ideas, and your reactions into your notes

- Summarizing the text in your notes in casual prose

- Reflecting on how the text relates to your topic and your stance on the topic

- Reflecting on how the text relates to others you’ve read

You need not perform such thorough reading with texts you don’t intend to use—e.g., if you determine that the source is too old to inform your work. However, the above list will ensure that you develop a nuanced and accurate understanding of the author’s perspective. Think of this process as part of the ongoing conversation: before you start expressing your ideas, you should listen carefully, ask follow-up questions to clarify what you’ve heard, and situate the ideas within the context of the bigger discussion.

The Annotated Bibliography

So far, you have discovered, evaluated, and begun to process your sources intellectually. Your next steps will vary based on your rhetorical situation, but it is possible that your teacher will ask you to write an annotated bibliography before or during the drafting process for your actual essay.

An annotated bibliography is a formalized exercise in the type of interpretation described throughout this section. An annotated bibliography is like a long works cited page, but underneath each citation is a paragraph that explains and analyzes the text. Examples are included in this section to give you an idea of what an annotated bibliography might look like.

Annotated bibliographies have a few purposes:

- To organize your research so you don’t lose track of where different ideas come from,

- To help you process texts in a consistent and thorough way, and

- To demonstrate your ongoing research process for your teacher.

This kind of writing can also be an end in itself: many scholars publish annotated bibliographies as research or teaching tools. They can be helpful for authors like you, looking for an introduction to a conversation or a variety of perspectives on a topic. As an example, consider the model annotated bibliography “What Does It Mean to Be Educated?” later in this chapter.

Although every teacher will have slightly different ideas about what goes into an annotated bibliography, I encourage my students to include the following:

- A brief summary of the main ideas discussed in the text and/or an evaluation of the rhetoric or argumentation deployed by the author.

- What are the key insights, arguments, or pieces of information included in the source? What is the author’s purpose? How does their language pursue that purpose?

- A consideration of the text’s place in the ongoing conversation about your topic.

- To what other ideas, issues, and texts is your text responding? How would you describe the intended audience? Does the author seem credible, referencing other “speakers” in the conversation?

- A description of the text’s use-value.

- Is the text useful? How do you predict you will use the text in your work?

You might note that your work in the CRAAP Test will provide useful answers for some of these questions.

Sometimes, I’ll also include a couple of compelling quotes in my annotations. Typically, I request that students write about 100 words for each annotation, but you should ask your teacher if they have more specific guidelines.

Your annotated bibliography will be an excellent tool as you turn to the next steps of research writing: synthesizing a variety of voices with your ideas and experiences. It is a quick reference guide, redirecting you to the texts you found most valuable; more abstractly, it will support you in perceiving a complex and nuanced conversation on your topic.

Research Methods: Drawing from Sources and Synthesizing

Finding Your Position, Posture, and Perspective

As you begin drafting your research essay, remember the conversation analogy: by using other voices, you are entering into a discussion that is much bigger than just you, even bigger than the authors you cite. However, what you have to say is important, so you are bringing together your ideas with others’ ideas from a unique interpretive standpoint. Although it may take you a while to find it, you should be searching for your unique position in a complex network of discourse.

Here are a few questions to ask yourself as you consider this:

- How would I introduce this topic to someone who is completely unfamiliar?

- What are the major viewpoints on this topic? Remember that very few issues have only two sides.

- With which viewpoints do I align? With which viewpoints do I disagree? Consider agreement (“Yes”), disagreement (“No”), and qualification (“Yes, but…”).

- What did I know about this issue before I began researching? What have I learned so far?

- What is my rhetorical purpose with this project? If your purpose is to argue a position, be sure that you feel comfortable with the terms and ideas discussed in the previous section on argumentation.

Articulating Your Claim

Once you’ve started to catch the rhythm of the ongoing conversation, it’s time to find a way to put your perspective into words. Bear in mind that your thesis statement should evolve as you research, draft, and revise: you might tweak the wording, adjust your scope, change your position or even your entire topic in the course of your work.

Because your thesis is a “working thesis” or “(hypo)thesis,” you should use the following strategies to draft your thesis but be ready to make adjustments along the way.

In Chapter 6, we introduced the T3, Occasion/Position, and Embedded Thesis models. As a refresher,

- A T3 statement articulates the author’s stance, then offers three supporting reasons, subtopics, or components of the argument.

Throughout history, women have been legally oppressed by different social institutions, including exclusion from the workplace, restriction of voting rights, and regulations of healthcare.

- An Occasion/Position statement starts with a statement of relevance related to the rhetorical occasion, then articulates the author’s stance.

Recent Congressional activity in the U.S. has led me to wonder how women’s freedoms have been restricted throughout history. Women have been legally oppressed by many different institutions since the inception of the United States.

- An Embedded Thesis presents the research question, perhaps with a gesture to the answer(s). This strategy requires that you clearly articulate your stance somewhere later in your paper, at a point when your evidence has led you to the answer to your guiding question.

Many people would agree that women have experienced oppression throughout the history of the United States, but how has this oppression been exercised legally through different social institutions?

Of course, these are only three strategies to write a thesis. You may use one of them, combine several of them, or use a different strategy entirely.

To build on these three strategies, we should look at three kinds of claims: three sorts of postures that you might take to articulate your stance as a thesis.

- Claim of Phenomenon: This statement indicates that your essay will explore a measurable but arguable happening.

Obesity rates correlate with higher rates of poverty.

Claims of phenomenon are often more straightforward, but should still be arguable and worth discussion.

- Claim of Evaluation: This statement indicates that your essay will determine something that is better, best, worse, or worst in regard to your topic.

The healthiest nations are those with economic safety nets.

Claims of evaluation require you to make an informed judgment based on evidence. In this example, the student would have to establish a metric for “healthy” in addition to exploring the way that economic safety nets promote healthful behaviors—What makes someone “healthy” and why are safety nets a pathway to health?

- Claim of Policy: This statement indicates that your essay will propose a plan of action to best address an issue.

State and federal governments should create educational programs, develop infrastructure, and establish food-stamp benefits to promote healthy eating for people experiencing poverty.

Claims of policy do the most heavy lifting: they articulate a stance that requires action, from the reader or from another stakeholder. A claim of policy often uses the word “should.”

You may notice that these claims can be effectively combined at your discretion. Sometimes, when different ideas overlap, it’s absolutely necessary to combine them to create a cohesive stance. For instance, in the example above, the claim of policy would require the author to establish a claim of phenomenon, too: before advocating for action, the author must demonstrate what that action responds to. For more practice, check out the activity in the following section titled “Articulating Your Claim — Practicing Thesis Development.”

Situating Yourself Using Your Research

While you’re drafting, be diligent and deliberate with your use of other people’s words, ideas, and perspectives. Foreground your thesis (even if it’s still in progress) and use paraphrases, direct quotes, and summary in the background to explain, support, complicate, or contrast your perspective.

Depending on the work you’ve done to this point, you may have a reasonable body of quotes, summaries, and paraphrases that you can draw from. Whether or not you’ve been collecting evidence throughout your research process, be sure to return to the original sources to ensure the accuracy and efficacy of your quotes, summaries, and paraphrases.

In Section 2, we encountered paraphrasing, quoting, and summarizing for a text wrestling essay, but let’s take a minute to revisit them in this new rhetorical situation. How do you think using support in a research paper is different from using support in an analysis?

A direct quote uses quotation marks (“ ”) to indicate where you’re borrowing an author’s words verbatim in your own writing. Use a direct quote if someone else wrote or said something in a distinctive or particular way and you want to capture their words exactly.

Direct quotes are good for establishing ethos and providing evidence. In a research essay, you will be expected to use some direct quotes; however, too many direct quotes can overwhelm your thesis and actually undermine your sense of ethos. Your research paper should strike a balance between quoting, paraphrasing, and summarizing—and articulating your own perspective!

Summarizing refers to the action of boiling down an author’s ideas into a shorter version in your own words. Summary demonstrates your understanding of a text, but it also can be useful in giving background information or making a complex idea more accessible.

When we paraphrase, we are processing information or ideas from another person’s text and putting it in our own words. The main difference between paraphrase and summary is scope: if summarizing means rewording and condensing, then

paraphrasing means rewording without drastically altering length. However, paraphrasing is also generally more faithful to the spirit of the original; whereas a summary requires you to process and invites your own perspective, a paraphrase ought to mirror back the original idea using your own language.

Paraphrasing is helpful for establishing background knowledge or general consensus, simplifying a complicated idea, or reminding your reader of a certain part of another text. It is also valuable when relaying statistics or historical information, both of which are usually more fluidly woven into your writing when spoken with your own voice.

Each of these three tactics should support your argument: you should integrate quotes, paraphrases, and summary in with your own writing. Below, you can see three examples of these tools. Consider how the direct quote, the paraphrase, and the summary each could be used to achieve different purposes.

Original Passage

It has been suggested (again rather anecdotally) that giraffes do communicate using infrasonic vocalizations (the signals are verbally described to be similar—in structure and function—to the low-frequency, infrasonic “rumbles” of elephants). It was further speculated that the extensive frontal sinus of giraffes acts as a resonance chamber for infrasound production. Moreover, particular neck movements (e.g. the neck stretch) are suggested to be associated with the production of infrasonic vocalizations.1

|

Quote |

Paraphrase |

Summary |

|

Some zoological experts have pointed out that the evidence for giraffe hums has been “rather anecdotally” reported (Baotic et al. 3). However, some scientists have “speculated that the extensive frontal sinus of giraffes acts as a resonance chamber for infrasound production” (Ibid. 3). |

Giraffes emit a low-pitch noise; some scientists believe that this hum can be used for communication with other members of the social group, but others are skeptical because of the dearth of research on giraffe noises. According to Baotic et al., the anatomy of the animal suggests that they may be making deliberate and specific noises (3). |

Baotic et al. conducted a study on giraffe hums in response to speculation that these noises are used deliberately for communication.

|

These examples also demonstrate additional citation conventions worth noting:

- A parenthetical in-text citation is used for all three forms. (In MLA format, this citation includes the author’s last name and page number.) The purpose of an in-text citation is to identify key information that guides your reader to your Works Cited page (or Bibliography or References, depending on your format).

- If you use the author’s name in the sentence, you do not need to include their name in the parenthetical citation.

- If your material doesn’t come from a specific page or page range, but rather from the entire text, you do not need to include a page number in the parenthetical citation.

- If there are many authors (generally more than three), you can use “et al.” to mean “and others.”

- If you cite the same source consecutively in the same paragraph (without citing any other sources in between), you can use “Ibid.” to mean “same as the last one.”

There are infinite ways to bring evidence into your discussion,2 but for now, let’s revisit a formula that many students find productive as they find their footing in research writing: Front-load + Quote/Paraphrase/Summarize + Cite + Explain/elaborate/analyze.

|

Front-load + (1-2 sentences) |

Quote, paraphrase, or summarize + |

(cite) + |

Explain, elaborate, analyze (2-3 sentences) |

|

Set your reader up for the quote using a signpost (also known as a “signal phrase”). Don’t drop quotes in abruptly: by front-loading, you can guide your reader’s interpretation. |

Use whichever technique is relevant to your rhetorical purpose at that exact point. |

Use an in-text citation appropriate to your discipline. It doesn’t matter if you quote, paraphrase, or summarize—all three require a citation |

Perhaps most importantly, you need to make the value of this evidence clear to the reader. What does it mean? How does it further your thesis? |

This might feel formulaic and forced at first, but following these steps will ensure that you give each piece of evidence thorough attention.

What might this look like in practice?

(1) Humans and dolphins are not the only mammals with complex systems of communication. As a matter of fact, (2) some scientists have “speculated that the extensive frontal sinus of giraffes acts as a resonance chamber for infrasound production” ((3) Baotic et al. 3). (4) Even though no definitive answer has been found, it’s possible that the structure of a giraffe’s head allows it to create sounds that humans may not be able to hear. This hypothesis supports the notion that different species of animals develop a sort of “language” that corresponds to their anatomy.

1. Front-load

Humans and dolphins are not the only mammals with complex systems of communication. As a matter of fact,

2. Quote

some scientists have “speculated that the extensive frontal sinus of giraffes acts as a resonance chamber for infrasound production”

3. Cite

(Baotic et al. 3).

4. Explain/elaborate/analyze

Even though no definitive answer has been found, it’s possible that the structure of a giraffe’s head allows it to create sounds that humans may not be able to hear. This hypothesis supports the notion that different species of animals develop a sort of “language” that corresponds to their anatomy.

Extended Quotes

A quick note on block quotes: Sometimes, you may find it necessary to use a long direct quote from a source. For instance, if there is a passage that you plan to analyze in-depth or throughout the course of the entire paper, you may need to reproduce the whole thing. You may have seen other authors use block quotes in the course of your research. In the middle of a sentence or paragraph, the text will break into a long direct quote that is indented and separated from the rest of the paragraph.

There are occasions when it is appropriate for you to use block quotes, too, but they are rare. Even though long quotes can be useful, quotes long enough to block are often too long. Using too much of one source all at once can overwhelm your own voice and analysis, distract the reader, undermine your ethos, and prevent you from digging into a quote. It’s typically a better choice to abridge (omit words from the beginning or end of the quote, or from the middle using an ellipsis […]), break up (split one long quote into two or three shorter quotes that you can attend to more specifically), or paraphrase a long quote, especially because that gives you more space for the last step of the formula above.

If, in the rare event that you must use a long direct quote, one which runs more than four lines on a properly formatted page, follow the guidelines from the appropriate style guide. In MLA format, block quotes are: (a) indented one inch from the margin, (b) double-spaced, (c) not in quotation marks, and (d) use original end-punctuation and an in-text citation after the last sentence. The paragraph will continue after the block quote without any indentation.

Readerly Signposts

Signposts are phrases and sentences that guide a reader’s interpretation of the evidence you are about to introduce. Readerly signposts are also known as “signal phrases” because they give the reader a warning of your next move. In addition to foreshadowing a paraphrase, quote, or summary, though, your signposts can be active agents in your argumentation.

Before using a paraphrase, quote, or summary, you can prime your reader to understand that evidence in a certain way. For example, let’s take the imaginary quote, “The moon landing was faked in a sound studio by Stanley Kubrick.”

[X] insists, “The moon landing was faked in a sound studio by Stanley Kubrick.”

Some people believe, naively, that “The moon landing was faked in a sound studio by Stanley Kubrick.”

Common knowledge suggests that “The moon landing was faked in a sound studio by Stanley Kubrick.”

[X] posits that “The moon landing was faked in a sound studio by Stanley Kubrick.”

Although some people believe otherwise, the truth is that “The moon landing was faked in a sound studio by Stanley Kubrick.”

Although some people believe that “The moon landing was faked in a sound studio by Stanley Kubrick,” it is more likely that…

Whenever conspiracy theories come up, people like to joke that “The moon landing was faked in a sound studio by Stanley Kubrick.”

The government has conducted many covert operations in the last century: “The moon landing was faked in a sound studio by Stanley Kubrick.”

What does each signpost do to us, as readers, encountering the same quote?

A very useful resource for applying these signposts is the text They Say, I Say, which you may be able to find online or at your school’s library.

Addressing Counterarguments

As you recall from the chapter on argumentation, a good argument acknowledges other voices. Whether you’re trying to refute those counterarguments or find common ground before moving forward, it is important to include a diversity of perspectives in your argument. One highly effective way to do so is by using the readerly signpost that I call the naysayer’s voice.

Simply put, the naysayer is a voice that disagrees with you that you imagine into your essay. Consider, for example, this excerpt from Paul Greenough:

It appears that tigers cannot be accurately counted and that uncertainty is as endemic to their study as to the study of many other wildlife populations. In the meantime, pugmark counting continues. … In the end, the debate over numbers cannot be resolved; while rising trends were discernible through the 1970s and 1980s, firm baselines and accurate numbers were beyond anyone’s grasp.

CRITIC: Are you emphasizing this numbers and counting business for some reason?

AUTHOR: Yes. I find it instructive to compare the degree of surveillance demanded by the smallpox eradication campaign…with the sketchy methods sufficient to keep Project Tiger afloat. …

CRITIC: Maybe numbers aren’t as central to these large state enterprises as you assume?

AUTHOR: No, no—they live and die by them.3

Notice the advantages of this technique:

- Greenough demonstrates, first and foremost, that the topic he’s considering is part of a broad conversation involving many voices and perspectives.

- He is able to effectively transition between ideas.

- He controls the counterargument by asking the questions he wants to be asked.

Give it a shot in your own writing by adding a reader’s or a naysayer’s voice every few paragraphs: imagine what a skeptical, curious, or enthusiastic audience might say in response to each of your main points.

Revisiting Your Research Question, Developing an Introduction, and Crafting a Conclusion

Once you’ve started synthesizing ideas in your drafting process, you should frequently revisit your research question to refine the phrasing and be certain it still encompasses your concerns. During the research and drafting process, it is likely that your focus will change, which should motivate you to adjust, pivot, complicate, or drastically change your path of inquiry and working thesis. Additionally, you will acquire new language and ideas as you get the feel for the conversation. Use the new jargon and concepts to hone your research question and thesis.

Introductions

Introductions are the most difficult part of any paper for me. Not only does it feel awkward, but I often don’t know quite what I want to say until I’ve written the essay. Fortunately, we don’t have to force out an intro before we’re ready. Give yourself permission to draft out of order! For instance, I typically write the entire body of the essay before returning to the top to draft an introduction.

If you draft out of order, though, you should dedicate time to crafting an effective introduction before turning in the final draft. The introduction to a paper is your chance to make a first impression on your reader. You might be establishing a conceptual framework, setting a tone, or showing the reader a way in. Furthermore, due to the primacy effect, readers are more likely to remember your intro than most of the rest of your essay.

In this brief section, I want to note two pet peeves for introductions, and then offer a handful of other possibilities.

Don’t

Avoid these two techniques:

- Starting with fluffy, irrelevant, or extremely general statements. Sometimes, developing authors make really broad observations or facts that just take up space before getting to the good stuff. You can see this demonstrated in the “Original” version of the student example below.

- Offering a definition for something that your audience already knows. At some point, this method became a stock-technique for starting speeches, essays, and other texts: “Merriam Webster defines x as….” You’ve probably heard it before. As pervasive as this technique is, though, it is generally ineffective for two reasons: (1) it is hackneyed—overused to the point of meaninglessness, and (2) it rarely offers new insight—the audience probably already has sufficient knowledge of the definition. There is an exception to this point, though! You can overcome issue #2 by analyzing the definition you give: does the definition reveal something about our common-sense that you want to critique? Does it contradict or overlook connotations? Do you think the definition is too narrow, too broad, or too ambiguous? In other words, you can use the definition technique as long as you’re doing something with the definition.

Do

These are a few approaches to introductions that my students often find successful. Perhaps the best advice I can offer, though, is to try out a lot of different introductions and see which ones feel better to you, the author. Which do you like most, and which do you think will be most impactful to your audience?

- Telling a story. Not only will this kick your essay off with pathos and specificity, but it can also lend variety to the voice you use throughout the rest of your essay. A story can also provide a touchstone, or a reference point, for you and your reader; you can relate your argument back to the story and its characters as you develop more complex ideas.

- Describing a scene. Similarly, thick description can provide your reader a mental image to grasp before you present your research question and thesis. This is the technique used in the model below.

- Asking a question. This is a common technique teachers share with their students when describing a “hook.” You want your reader to feel curious, excited, and involved as they start reading your essay, and posing a thought-provoking question can bring them into the conversation too.

- Using a striking quote or fact. Another “hook” technique: starting off your essay with a meaningful quote, shocking statistic, or curious fact can catch a reader’s eye and stimulate their curiosity.

- Considering a case study. Similar to the storytelling approach, this technique asks you to identify a single person or occurrence relevant to your topic that represents a bigger trend you will discuss.

- Relating a real or imaginary dialogue. To help your readers acclimate to the conversation themselves, show them how people might talk about your topic. This also provides a good opportunity to demonstrate the stakes of the issue—why does it matter, and to whom?

- Establishing a juxtaposition. You might compare two seemingly unlike ideas, things, or questions, or contrast two seemingly similar ideas, things, or questions in order to clarify your path of inquiry and to challenge your readers’ assumptions about those ideas, things or questions.

Here’s an example of a student’s placeholder introduction in their draft, followed by a revised version using the scene description approach from above. He tried out a few

of the strategies above before settling on the scene description for his revision. Notice how the earlier version “buries the lede,” as one might say—hides the most interesting, relevant, or exciting detail. By contrast, the revised version is active, visual, and engaging.

Original:

Every year over 15 million people visit Paris, more than any other city in the world. Paris has a rich, artistic history, stunning architecture and decadent mouth-watering food. Almost every visitor here heads straight for the Eiffel Tower (“Top destinations” 2014). Absorbing the breathtaking view, towering over the metropolis below, you might notice something missing from the Parisian landscape: tall buildings. It’s easy to overlook but a peculiar thing. Around the world, most mega cities have hundreds of towering skyscrapers, but here in Paris, the vast majority of buildings are less than six stories tall (Davies 2010). The reason lies deep below the surface in the Paris underground where an immense cave system filled with dead bodies is attracting a different kind of visitor.4

Revised:

On a frigid day in December of 1774, residents of a small walled district in Paris watched in horror as the ground before them began to crack and shift. Within seconds a massive section of road collapsed, leaving behind a gaping chasm where Rue d’Enfer (Hell Street) once stood. Residents peeked over the edge into a black abyss that has since become the stuff of wonder and nightmares. What had been unearthed that cold day in December, was an ancient tunnel system now known as The Empire of the Dead.5

You may notice that neither of these model introductions articulates a thesis statement or a research question. How would you advise this student to transition into the central, unifying insight of their paper?

Conclusions

A close second to introductions, in terms of difficulty, are conclusions. Due to the recency effect, readers are more likely to remember your conclusion than most of the rest of your essay.

Most of us have been trained to believe that a conclusion repeats your thesis and main arguments, perhaps in different words, to remind the reader what they just read—or to fluff up page counts.

This is a misguided notion. True, conclusions shouldn’t introduce completely new ideas, but they shouldn’t only rehearse everything you’ve already said. Rather, they should tie up loose ends and leave the reader with an extending thought—something more to meditate on once they’ve left the world you’ve created with your essay. Your conclusion is your last chance to speak to your reader on your terms based on the knowledge you have now shared; repeating what you have already established is a wasted opportunity.

Instead, here are few other possibilities. (You can include all, some, or none of them.)

- Look back to your introduction. If you told a story, shared a case study, or described a scene, you might reconsider that story, case study, or scene with the knowledge developed in the course of your paper. Consider the “ouroboros”—the snake eating its own head. Your conclusion can provide a satisfying circularity using this tactic.

- Consider what surprised you in your research process. What do those surprises teach us about commonsense assumptions about your topic? How might the evolution of your thought on a topic model the evolution you expect from your readers?

- End with a quote. A final thought, meaningfully articulated, can make your readers feel settled and satisfied.

- Propose a call-to-action. Especially if your path of inquiry is a matter of policy or behavior, tell the reader what they should do now that they have seen the issue from your eyes.

- Gesture to questions and issues you can’t address in the scope of your paper. You might have had to omit some of your digressive concerns in the interest of focus. What remains to be answered, studied, or considered?

Here’s an example of a placeholder conclusion in a draft, followed by a revised version using the “gesture to questions” and “end with a quote” approach from above. You may not be able to tell without reading the rest of the essay, but the original version simply restates the main points of each paragraph. In addition to being repetitive, the original is also not very exciting, so it does not inspire the reader to keep thinking about the topic. On the other hand, the revised version tries to give the reader more to chew on: it builds from what the paper establishes to provoke more curiosity and lets the subject continue to grow.

Original:

In conclusion, it is likely that the space tourism industry will flourish as long as venture capitalists and the private sector bankroll its development. As noted in this paper, new technology will support space tourism and humans are always curious to see new places. Space tourism is currently very expensive but it will become more affordable. The FAA and other government agencies will make sure it is regulated and safe.

Revised:

It has become clear that the financial, regulatory, and technological elements of space tourism are all within reach for humanity—whether in reality or in our imaginations. However, the growth of a space tourism industry will raise more and more questions: Will the ability to leave our blue marble exacerbate income inequity? If space tourism is restricted to those who can afford exorbitant costs, then it is quite possible that the less privileged will remain earthbound. Moreover, should our history of earthly colonization worry us for the fate of our universe? These questions and others point to an urgent constraint: space tourism might be logistically feasible, but can we ensure that what we imagine will be ethical? According to Carl Sagan, “Imagination will often carry us to worlds that never were. But without it we go nowhere” (2).6

Activities

Research Scavenger Hunt

To practice using a variety of research tools and finding a diversity of sources, try to discover resources according to the following constraints. Once you find a source, you should make sure you can access it later—save it to your computer; copy a live, stable URL; request it from the library; and/or save it to your Library eShelf, if you have one. For this assignment, you can copy a URL or doi for digital resources or library call number for physical ones.

If you’re already working on a project, use your topic for this activity. If you don’t have a topic in mind, choose one by picking up a book, paper, or other written text near you: close your eyes and point to a random part of the page. Use the noun closest to your finger that you find vaguely interesting as a topic or search term for this exercise.

|

Research Tool |

URL, doi, or Call Number |

|

A peer-reviewed journal article through a database |

|

|

A source you bootstrapped using subject tags |

|

|

A newspaper article |

|

|

A source through Google |

|

|

A source originally cited in a Wikipedia article |

|

|

A physical text in your school’s library (book, DVD, microfilm, etc.) |

|

|

A source through Google Scholar |

|

|

A source you citation-mined from another source’s bibliography |

|

|

An eBook |

|

|

A text written in plain language |

|

|

A text written in discipline-specific jargon |

|

|

A text that is not credible |

|

|

A text older than twenty years |

|

|

A text published within the last two years |

|

Identifying Fake News

To think more about credibility, accuracy, and truth, read “Fake news ‘symptomatic of crisis in journalism’” from Al Jazeera. Then, test your skills using this fake news quiz game.

Interacting with Sources Graphic Organizer

The following graphic organizer asks you to apply the skills from the previous section using a text of your choice. Complete this graphic organizer to practice critical encounters with your research and prepare to integrate information into your essay.

a. Discovering a Source: Find a source using one of the methods described in this chapter; record which method you used below (e.g., “Google Scholar” or “bootstrapped a library article”).

b. Evaluating Credibility and Use-Value: Put your source through the CRAAP Test to determine whether it demonstrates credibility and use-value. Write responses for each element that practice reading with the grain and reading against the grain.

|

|

With Grain (Believer) “This source is great!” |

Against Grain (Doubter) “This source is absolute garbage!” |

|

Currency |

|

|

|

Relevance |

|

|

|

Accuracy |

|

|

|

Authority |

|

|

|

Purpose |

|

|

c. Citation: Using citation and style resources like Purdue OWL for guidance, write an accurate citation for this source for a Works Cited page.

d. Paraphrase/Quote/Summarize: Choose a “golden line” from the source.

First, copy the quote, using quotations marks, and include a parenthetical in-text citation.

Second, paraphrase the quote and include a parenthetical in-text citation.

Third, summarize the main point of the source and include a parenthetical in-text citation; you may include the quote if you see fit.

e. Integrating Information: Using your response from part d, write a sample paragraph that integrates a quote, paraphrase, or summary. Use the formula discussed earlier in this chapter (front-load + P/Q/S + explain/elaborate/analyze)

Articulating Your Claim – Practicing Thesis Development

To practice applying the strategies for developing and revising a thesis statement explored in this chapter, you will write and revise a claim based on constraints provided by your groupmates. This activity works best with at least two other students.

Part One – Write

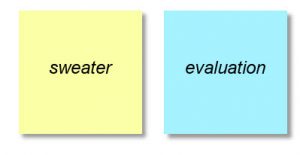

First, on a post-it note or blank piece of paper, write any article of clothing. Then, choose one type of claim (Claim of Phenomenon, Claim of Evaluation, or Claim of Policy, introduced in “Research Methods: Drawing from Sources and Synthesizing”) and write “Phenomenon,” “Evaluation,” or “Policy” on a different post-it note or blank piece of paper.

Exchange your article of clothing with one student and your type of claim with another. (As long as you end up with one of each that you didn’t come up with yourself, it doesn’t matter how you rotate.) Now, write a thesis statement using your choice of strategy:

T3 (Throughout history, women have been legally oppressed by different social institutions, including exclusion from the workplace, restriction of voting rights, and regulations of healthcare.)

O/P (Recent Congressional activity in the U.S. has led me to wonder how women’s freedoms have been restricted throughout history. Women have been legally oppressed by many different institutions since the inception of the United States.)

Embedded Thesis (Many people would agree that women have experienced oppression throughout the history of the United States, but how has this oppression been exercised legally through different social institutions?)

Your thesis should make a claim about the article of clothing according to the post-its you received. For example

Now that it’s November, it’s time to break out the cold weather clothing. When you want to be both warm and also fashionable, a striped wool sweater is the best choice.

Part Two – Revise

Now, write one of the rhetorical appeals (logos, pathos, or ethos) on a new post-it note. Exchange with another student. Revise your thesis to appeal predominantly to that rhetorical appeal.

Example:

|

Original: Now that it’s November, it’s time to break out the cold weather clothing. When you want to be |

|

Revised: With the colder months looming, we are obliged to bundle up. Because they help you maintain consistent and comfortable body temperature, wool sweaters are the best option. |

Finally, revise your thesis once more by adding a concession statement.

Example:

|

Original: With the colder months looming, we are obliged to bundle up. Because they help you maintain consistent and comfortable body temperature, wool sweaters are the best option. |

Revised: With the colder months looming, we are obliged to bundle up. Even though jackets are better for rain or snow, a sweater is a versatile and functional alternative. Because they help you maintain consistent and comfortable body temperature, wool sweaters are the best option. |

Guiding Interpretation (Readerly Signposts)

In the organizer on the next page, create a signpost for each of the quotes in the left column that reflects the posture in the top row.

|

|

Complete faith |

Uncertainty |

Cautious disbelief |

“Duh” |

|

“Peanut butter and jelly sandwiches are a nutritious part of a child’s lunch.” |

|

Most parents have wondered if “peanut butter and jelly sandwiches are a nutritious part of a child’s lunch.” |

|

|

|

“The bees are dying rapidly.” |

|

|

Even though some people argue that “the bees are dying rapidly,” it may be more complicated than that. |

|

|

“Jennifer Lopez is still relevant.” |

We can all agree, “Jennifer Lopez is still relevant.” |

|

|

|

|

“Morality cannot be learned.” |

|

|

|

It should be obvious that “morality cannot be learned.” |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Model Texts by Student Authors

What Does It Mean to Be Educated?7

Broton, K. and Sara Goldrick-Rab. “The Dark Side of College (Un)Affordability: Food and Housing Insecurity in Higher Education.” Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, vol. 48, no. 1, 2016, pp. 16-25. Taylor & Francis, doi: 10.1080/00091383.2016.1121081.

This article shines a light on food and housing insecurity in higher education. It makes the argument that not having adequate meals or shelter increase the likelihood of receiving poorer grades and not finishing your degree program. There are a few examples of how some colleges and universities have set up food pantries and offer other types of payment plan or assistance programs. It also references a longitudinal study that follows a group of students from higher education through college and provides supporting data and a compelling case study. This is a useful article for those that would like to bring more programs like these to their campus. This article is a good overview of the problem, but could go a step further and provide starter kits for those interested in enacting a change in their institution.

Davis, Joshua. “A Radical Way of Unleashing a Generation of Geniuses.” Wired, 15 October 2013.

This article profiles a teacher in a small school in an impoverished area of Mexico. He has created a space where students are encouraged to learn by collaborating and testing, not by lecture. The article ties the current system of learning to being rooted in the industrial age, but goes on to note that this is negative because they have not adapted to the needs of companies in the modern age. This article is particularly useful to provide examples of how relinquishing control over a classroom is beneficial. It also has a timeline of alternative teaching theorists and examples of schools that are breaking the mold of traditional education. My only critique of the article is that, although it presents numerous examples of a changing education system, it is very negative regarding the prospects for education.

Davis, Lois M., and Robert Bozick, Jennifer L. Steele, Jessica Saunders, and Jeremy N.V. Miles. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Correctional Education: A Meta-Analysis of Programs That Provide Education to Incarcerated Adults. RAND, 2013.

This meta-analysis from the RAND Corporation, a non-partisan think tank, reviews research done on the topic of education in correctional institutions. The facts show that when incarcerated people have access to education, recidivism drops, career prospects improve, and taxpayers save money. There are differences based on the type of education (vocational versus general education) and the methods (using technology had better outcomes). It is interesting that the direct cost of the education was offset by the reduced recidivism rate, to the point where it is more cost effective to educate inmates. This analysis would be particularly useful for legislators and correctional institution policy makers. I did not see in this research any discussion of student selection; I believe there may be some skewed data if the people choosing to attend education may already be more likely to have positive outcomes.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. The Complete Writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Wm. H. Wise & Co., 1929.

In this collection of writing, Emerson insists that primary inspiration comes from nature and education is the vehicle that will “awaken him to the knowledge of this fact.” Emerson sees the nonchalance of children as something to aspire to, which should be left alone. He is critical of parents (and all adults) in diminishing the independence of children. This source is particularly useful when considering the alignment of educators and pupils. Emerson contends that true genius is novel and is not understood unless there is proper alignment between educators and pupils. I think this is a valuable source for pupils by increasing their level of “self-trust.”

Gladwell, Malcolm. David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits and the Art of Battling Giants, Little, Brown & Co., 2014.

Malcolm Gladwell generally has some interesting takes on the world at large. In this book he looks at what is considered a strength and where it may originate. The most interesting part of his argument, I believe, is that which states that a perceived deficiency, like dyslexia, may serve as a catalyst for increased ability in another area. Gladwell says that compensation learning can be achieved when there is a desirable difficulty. This book, and much of Gladwell’s work, can be especially useful for those which want to look beyond the surface of the world to make sense of seemingly random data. Much of the book rang true to me since I have had an especially hard time reading at an adequate speed, but can listen to an audiobook and recite it almost verbatim in an essay.

Hurley, J. Casey. “What Does It Mean to Be Educated?” Midwestern Educational Researcher, vol. 24, no. 4, 2011, p.2-4.

In his keynote speech, the speaker sets forth an argument for his understanding of an “educated” person. The six virtues he espouses are: understanding, imagination, strength, courage, humility, and generosity. These, he states, can lift a person past the baseline of human nature which is instinctively “ignorant, intellectually incompetent, weak, fearful of truth, proud and selfish” (3). I prefer this definition over any other that I have come across. I have been thinking a bit about the MAX attacks and how Micah Fletcher has responded to the attention he has received. I am proud to see a 21 year old respond with the level of awareness around social justice issues that he carries. These traits that he exemplifies, would not likely exist in this individual if it not for the education he has received at PSU.

Introduction to El Sistema. Annenberg Learner Firm, 2014. Films Media Group, 2016.

This video profiles El Sistema. El Sistema was designed in Venezuela by José Antonio Abreu in 1975 as a method for teaching social citizenship. The method is to have groups of children learn how to play orchestral music. It is community-based (parents participate) and more experienced members of the group are expected to teach younger students. In Venezuela, this program is government-funded as a social program, not an arts program. This video would be useful for those that are interested in how arts can be used for social change. I thought it was interesting that one of the first tasks that groups perform is to construct a paper violin. I am a fan of breaking down a complicated item, like the instrument, to its constituent parts.

Petrosino, Anthony and Carolyn Turpin-Petrosino, and John Buehler. “‘Scared Straight’ and Other Juvenile Awareness Programs for Preventing Juvenile Delinquency.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 589, 2003, pp. 41-62. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002796.pub2

This article is a meta-analysis of Scared Straight and similar crime deterrence programs. These programs were very popular when I was in high school and are still in use today. The analysis shows that these programs actually increase the likelihood for crime, which is the opposite effect of the well-meaning people that implement such programs. This is particularly useful for those that are contemplating implementing such a program. Also, it is a good example of how analysis should drive decisions around childhood education. I do remember programs like this from when I was in high school, but I was not because I was not considered high-risk enough at the time. It would be interesting to see if the data is detailed enough to see if selection bias affected some of the high rates of incarceration for these offenders.

Robinson, Ken. “Do Schools Kill Creativity?” TED, February 2006.

In this video Ken Robinson simply states that creativity is as important as literacy. Creativity, he defines, as “the process of having original ideas that have value.” Robinson states that children are regrettably “educated out of creativity” and that is imperative that we do not stigmatize failure. To emphasize this point he gives an example of a cohort of children which would retire in 2065, but no one can possibly imagine what the world may look like then. This piece is particularly useful for the fact that it highlights the ways creativity may be stifled or encouraged. There are is a bit of conflating of creativity and ADHD in this video, but in either case the message is to listen and encourage the pupil as a whole being.

Smith, Karen. “Decolonizing Queer Pedagogy.” Journal of Women and Social Work, vol. 28, no. 4, 2013, pp. 468-470. SAGE, doi: 10.1177/0886109913505814.

`In Karen Smith’s essay, the purpose of education—at least the course entitled Queer Theories and Identities—is to “interrupt queer settler colonialism by challenging students to study the ways in which they inherit colonial histories and to insist that they critically question the colonial institutions through which their rights are sought” (469). This particular course is then, going beyond simply informing pupils, but attempting to interrupt oppressive patriarchal systems. This article is particularly useful as an example of education as social activism. This theme is not one that is explored greatly in other works and looks at education as a means of overthrowing the system, instead of pieces which may looking at increasing an individual’s knowledge or their contribution to society.

Pirates & Anarchy8

(Annotated Bibliography – see the proposal here and the final paper here)

“About Rose City Antifa.” Rose City Antifa. http://rosecityantifa.org/about/.

The “about” page of Rose City Antifa’s website has no author or date listed. It is referenced as a voice in the conversation around current political events. This is the anarchic group that took disruptive action during the Portland May Day rally, turning the peaceful demonstration into a destructive riot. This page on their website outlines some core beliefs regarding what they describe as the oppressive nature of our society’s structure. They specifically point to extreme right wing political groups, so-called neo-nazis, as the antithesis of what antifa stands for. Along with this, they state that they acknowledge the frustration of “young, white, working-class men.” Antifa as a group intends to give these men a meaningful culture to join that doesn’t include racism in its tenets, but seeks freedom and equality for all. Action is held in higher regards than rhetoric. This voice is important to this body of research as a timely and local consideration on how anarchy and anarchic groups relate to piratical acts in the here and now.

Chappell, Bill. “Portland Police Arrest 25, Saying A May Day Rally Devolved Into ‘Riot’.” Oregon Public Broadcasting, National Public Radio, 2 May 2017.

This very short news report documents the events at the Portland May Day Rally this past May 2nd. What began as a peaceful rally for workers’ rights became a violent protest when it was taken over by a self-described anarchist group. The group vandalized property, set fires, and hurled objects at police. This is an example of recent riots by local anarchist groups that organize interruptions of other political group’s permitted demonstrations in order to draw attention to the anarchist agenda. The value of this report is that it shows that anarchy is still a philosophy adopted by certain organizations that are actively seeking to cause disruption in political conversation.

Dawdy, S. L. & J. Bonni. “Towards a General Theory of Piracy.” Anthropological Quarterly, vol. 85, no. 3, 2012, pp. 673-699. Project MUSE, doi: 10.1353/anq.2012.0043.

Comparisons are drawn between Golden Age pirates and current intellectual pirates in this in-depth article looking at piracy over time. The authors offer a definition of piracy as “a form of morally ambiguous property seizure committed by an organized group which can include thievery, hijacking, smuggling, counterfeiting, or kidnapping” (675). They also state that pirates are “organizations of social bandits” going on to discuss piracy as a rebellion against capitalist injustices (696). The intentional anarchic nature of the acts committed are a response to being left behind economically by political structures. The authors conclude with a warning that “we might look for a surge in piracy in both representation and action as an indication that a major turn of the wheel is about to occur” (696) These anthropological ideas reflect the simmering political currents we are experiencing now in 2017. Could the multiple recent bold acts of anarchist groups portend more rebellion in our society’s future? The call for jobs and fair compensation are getting louder and louder in western countries. If political structures cannot provide economic stability, will citizens ultimately decide to tear it all down? The clarity of the definitions in this article are helpful in understanding what exactly is a pirate and what their presence may mean to society at large.

Hirshleifer, Jack. “Anarchy and Its Breakdown.” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 103, no. 1, 1995, pp. 26-52.

This rather dense article is written around the question of the sustainability of anarchic organizations. The goals and activities are discussed in their most basic form in terms of resource gathering, distribution and defense. It does provide a solid definition of anarchy by stating, “anarchy is a social arrangement in which contenders struggle to conquer and defend durable resources, without effective regulation by either higher authorities or social pressures.” While social groups are connected in order to obtain resources, there is not hierarchy of leadership. The author does discuss the fragility of these groups as well. Agreement on a social contract is challenging as is remaining cohesive and resisting merging with other groups with different social contracts. This element of agreement on structure make sense in terms of piratical organizations. Captains are captains at the pleasure of the crew so long as his/her decision making enables the group as a whole to prosper. The anarchy definition is useful to bring understanding on what ties these groups together.

Houston, Chloe, editor. New Worlds Reflected: Travel and Utopia in the Early Modern Period, Ashgate, 2010.

This book, which is a collection of essays, explores the idea of utopia. The editor describes it in the introduction as “an ideal place which does not exist”—a notion that there is in human nature a desire to discover the “perfect” place, but that location is not attainable (1). The desire itself is key because of the exploration it sparks. There are three parts to the book, the second being “Utopian Communities and Piracy.” This section mostly contains essays that relate to explorations for the New World and pirate groups’ contributions that either helped or hindered the success of such expeditions. While there is much that is interesting here, especially in terms of “utopia” as a motivator, there is not much that lends information on piratical exploits. I’ll likely not use this source in my essay.

“I Am Not a Pirate.” This American Life, episode 616, National Public Radio, 5 May 2017, https://m.thisamericanlife.org/radio-archives/episode/616/i-am-not-a-pirate.