Assignment: Text wrestling Analysis

To practice critical, analytical thinking through the medium of writing, you will perform a text wrestling analysis and synthesize your findings in an essay driven by a central, unifying insight presented as a thesis and supported by evidence.

Assignment

First, you will determine which text it is that you’d like to analyze. Your teacher might provide a specific text or set of texts to choose from, or they may allow you to choose your own.

- If your teacher assigns a specific text, follow the steps in the next section.

- If your teacher assigns a set of texts to choose from, read each of them once. Then, narrow it down by asking yourself,

- Which texts were most striking or curious? Which raised the most questions for you as a reader?

- How do the texts differ from one another in content, form, voice, and genre?

- Which seem like the “best written”? Why?

- Which can you relate to personally?

- Try to narrow down to two or three texts that you particularly appreciate. Then try to determine which of these will help you write the best close reading essay possible. Follow the steps from #1 once you’ve determined your focus text.

- If your teacher allows you to choose any text you want, they probably did so because they want you to choose a text that means a lot to you personally.

- Consider first what medium (e.g., prose, film, music, etc.) or genre (e.g., essay, documentary, Screamo) would be most appropriate and exciting, keeping in mind any restrictions your teacher might have set.

- Then, brainstorm what topics seem relevant and interesting to you.

- Finally, try to encounter at least three or four different texts so you can test the waters.

- Now that you’ve chosen a focus text, you should read it several times using the active reading strategies contained in this section and the appendix. Consider what parts are contributing to the whole text, and develop an analytical perspective about that relationship. Try to articulate this analytical perspective as a working thesis—a statement of your interpretation which you will likely revise in some way or another. (You might also consider whether a specific critical lens seems relevant or interesting to your analysis.)

Next, you will write a 250-word proposal indicating which text you’ve chosen, what your working thesis is, and why you chose that text and analytical perspective. (This will help keep your teacher in the loop on your process and encourage you to think through your approach before writing.)

Finally, draft a text wrestling essay that analytically explores some part of your text using the strategies detailed in this section. Your essay will advance an interpretation that will

- help your audience understand the text differently (beyond basic plot/comprehension); and/or

- help your audience understand our world differently, using the text as a tool to illuminate the human experience.

Keep in mind, you will have to re-read your text several times to analyze it well and compile evidence. Consider forming a close reading discussion group to unpack your text collaboratively before you begin writing independently.

Your essay should be thesis-driven and will include quotes, paraphrases, and summary from the original text as evidence to support your points. Be sure to revise at least once before submitting your final draft.

Although you may realize as you evaluate your rhetorical situation, this kind of essay often values Standardized Edited American English, a dialect of the English language. Among other things, this entails a polished, “academic” tone. Although you need not use a thesaurus to find all the fanciest words, your voice should be less colloquial than in a descriptive personal narrative.

Before you begin, consider your rhetorical situation:

|

Subject: |

Occasion: |

|

How will this influence the way you write? |

How will this influence the way you write? |

|

Audience: |

Purpose: |

|

How will this influence the way you write? |

How will this influence the way you write? |

Guidelines for Peer Workshop

Guidelines for Peer Workshop

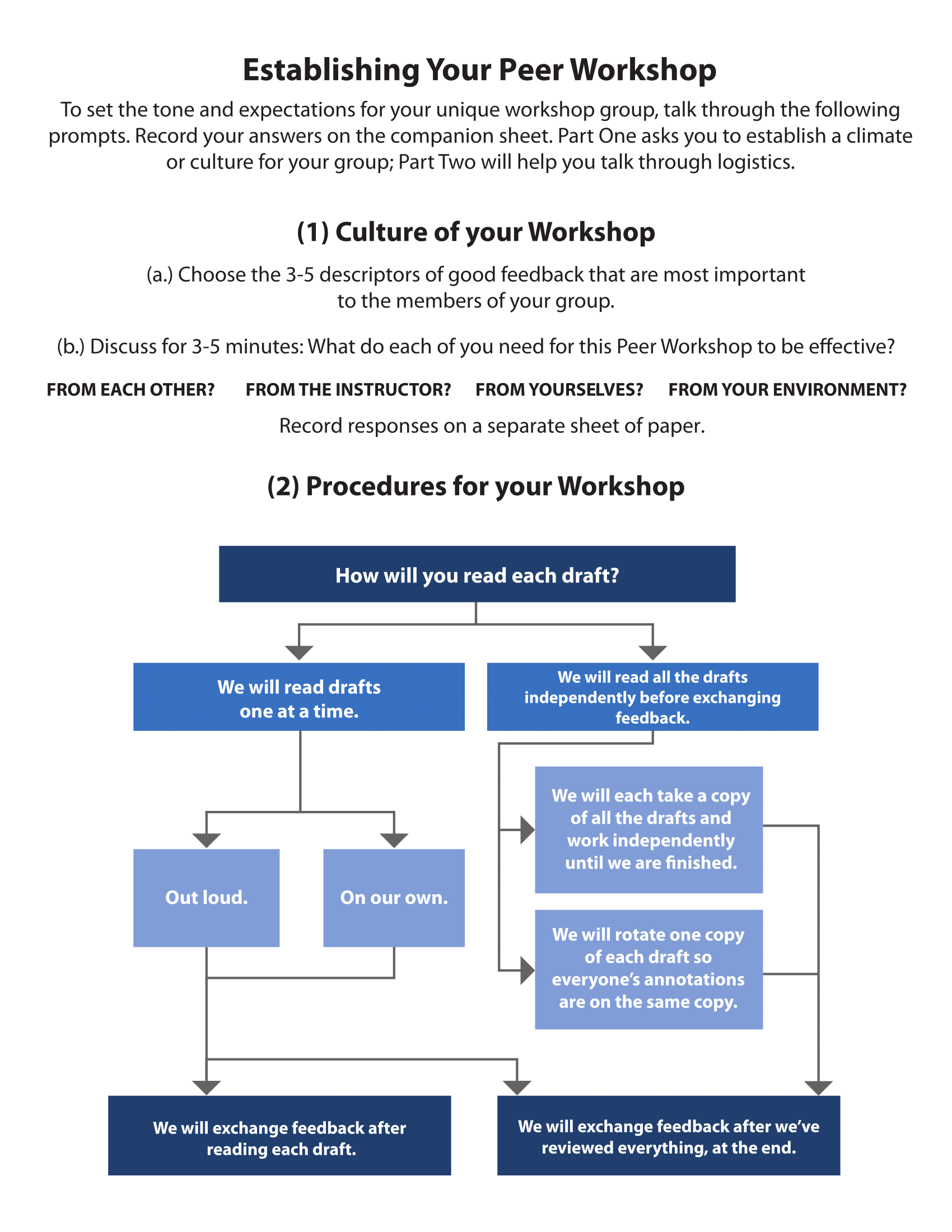

Before beginning the Peer Workshop and revision process, I recommend consulting the Revision Concepts and Strategies Appendix. In your Peer Workshop group (or based on your teacher’s directions), establish a process for workshopping that will work for you. You may find the flowchart titled “Establishing Your Peer Workshop” useful.

Establishing Peer Workshop Process:

Do you prefer written notes, or open discussion? Would you like to read all the drafts first, then discuss, or go one at a time? Should the author respond to feedback or just listen? What anxieties do you each have about sharing your writing? How will you provide feedback that is both critical and kind? How will you demonstrate respect for your peers?

One Example of a Peer Workshop Process

- Before the workshop, each author should spend several minutes generating requests for support (#1 below). Identify specific elements you need help on. Here are a few examples:

- I need help honing my thesis statement.

- Do you think my analysis flows logically?

- I’m not very experienced with in-text citations; can you make sure they’re accurate?

- Do you think my evidence is convincing enough?

- During the workshop, follow this sequence:

- Student A introduces their draft, distributes copies, and makes requests for feedback. What do you want help with, specifically?

- Student A reads their draft aloud while students B and C annotate/take notes. What do you notice as the draft is read aloud?

- Whole group discusses the draft; student A takes notes. Use these prompts as a reference to generate and frame your feedback. Try to identify specific places in your classmates’ essays where the writer is successful and where the writer needs support. Consider constructive, specific, and actionable feedback. What is the author doing well? What could they do better?

- What requests does the author have for support? What feedback do you have on this issue, specifically?

- Identify one “golden line” from the essay under consideration—a phrase, sentence, or paragraph that resonates with you. What about this line is so striking?

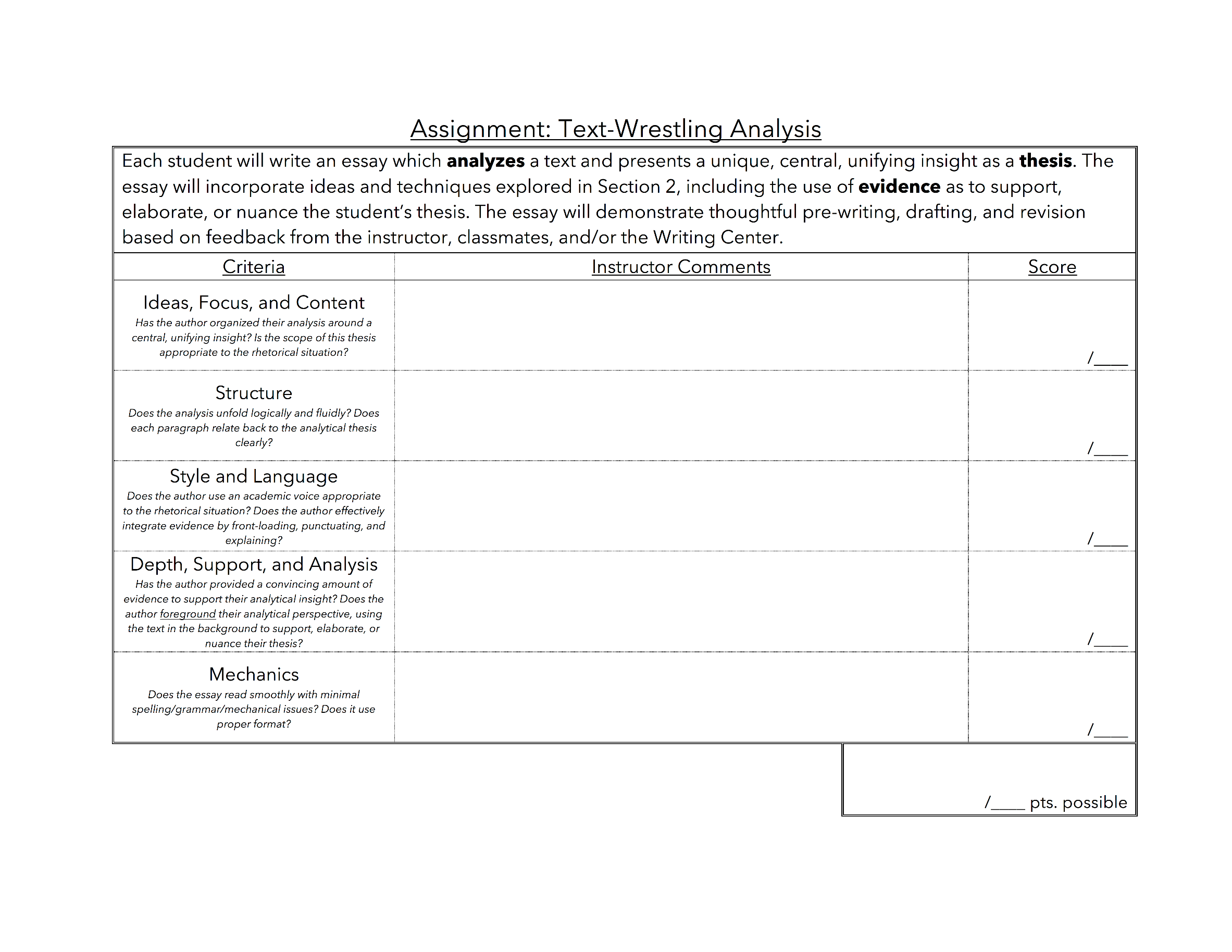

- Consult either the rubric included above or an alternate rubric, if your instructor has provided one. Is the author on track to meet the expectations of the assignment? What does the author do well in each of the categories? What could they do better?

- Ideas, Content, and Focus

- Structure

- Style and Language

- Depth, Support, and Reflection

- Mechanics

- What resonances do you see between this draft and others from your group? Between this draft and the exemplars you’ve read?

- Repeat with students B and C.

After the workshop, try implementing some of the feedback your group provided while they’re still nearby! For example, if Student B said your introduction needed more imagery, draft some new language and see if Student B likes the direction you’re moving in. As you are comfortable, exchange contact information with your group so you can to continue the discussion outside of class.

Model Text by Student Authors

To Suffer or Surrender? An Analysis of Dylan Thomas’s “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night”1

Death is a part of life that everyone must face at one point or another. The poem “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night” depicts the grief and panic one feels when a loved is approaching the end of their life, while presenting a question; is it right to surrender to death, or should it be resisted? In this poem Dylan Thomas opposes the idea of a peaceful passing, and uses various literary devices such as repetition, metaphor, and imagery to argue that death should be resisted at all costs.

The first thing that one may notice while reading Thomas’s piece is that there are key phrases repeated throughout the poem. As a result of the poem’s villanelle structure, both lines “Do not go gentle into that good night” and “Rage, rage against the dying of the light” (Thomas) are repeated often. This repetition gives the reader a sense of panic and desperation as the speaker pleads with their father to stay. The first line showcases a bit of alliteration of n sounds at the beginning of “not” and “night,” as well as alliteration of hard g sounds in the words “go” and “good.” These lines are vital to the poem as they reiterate its central meaning, making it far from subtle and extremely hard to miss. These lines add even more significance due to their placement in the poem. “Dying of the light” and “good night” are direct metaphors for death, and with the exception of the first line of the poem, they only appear at the end of a stanza. This structural choice is a result of the villanelle form, but we can interpret it to highlight the predictability of life itself, and signifies the undeniable and unavoidable fact that everyone must face death at the end of one’s life. The line “my father, there on the sad height” (Thomas 16) confirms that this poem is directed to the speaker’s father, the idea presented in these lines is what Thomas wants his father to recognize above all else.

This poem also has many contradictions. In the fifth stanza, Thomas describes men near death “who see with blinding sight” (Thomas 13). “Blinding sight” is an oxymoron, which implies that although with age most men lose their sight, they are wiser and enlightened, and have a greater understanding of the world. In this poem “night” is synonymous with “death”; thus, the phrase “good night” can also be considered an oxymoron if one does not consider death good. Presumably the speaker does not, given their desperation for their father to avoid it. The use of the word “good” initially seems odd, however, although it may seem like the speaker rejects the idea of death itself, this is not entirely the case. Thomas presents yet another oxymoron by saying “Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears” (Thomas 17). By referring to passionate tears as a blessing and a curse, which insinuates that the speaker does not necessarily believe death itself is inherently wrong, but to remain complicit in the face of death would be. These tears would be a curse because it is difficult to watch a loved one cry, but a blessing because the tears are a sign that the father is unwilling to surrender to death. This line is especially significant as it distinguishes the author’s beliefs about death versus dying, which are vastly different. “Good night” is an acknowledgement of the bittersweet relief of the struggles and hardships of life that come with death, while “fierce tears” and the repeated line “Rage, rage against the dying of the light” show that the speaker sees the act of dying as a much more passionate, sad, and angering experience. The presence of these oxymorons creates a sense of conflict in the reader, a feeling that is often felt by those who are struggling to say goodbye to a loved one.

At the beginning of the middle four stanzas they each begin with a description of a man, “Wise men… Good men…Wild men… Grave men…” (Thomas 4; 7; 10; 13). Each of these men have one characteristic that is shared, which is that they all fought against death for as long as they could. These examples are perhaps used in an attempt to inspire the father. Although the speaker begs their father to “rage” against death, this is not to say that they believe death is avoidable. Thomas reveals this in the 2nd stanza that “wise men at their end know dark is right” (Thomas 4), meaning that wise men know that death is inevitable, which in return means that the speaker is conscious of this fact as well. It also refers to the dark as “right”, which may seem contradicting to the notion presented that death should not be surrendered to; however, this is yet another example of the contrast between the author’s beliefs about death itself, and the act of dying. The last perspective that Thomas shows is “Grave men”. Of course, the wordplay of “grave” alludes to death. Moreover, similarly to the second stanza that referred to “wise men”, this characterization of “grave men” alludes to the speaker’s knowledge of impending doom, despite the constant pleads for their father to resist it.

Another common theme that occurs in the stanzas about these men is regret. A large reason the speaker is so insistent that his father does not surrender to the “dying of the light” is because the speaker does not want their father to die with regrets, and believes that any honorable man should do everything they can in their power to make a positive impact in the world. Thomas makes it clear that it is cowardly to surrender when one can still do good, no matter how small or seemingly insignificant.

All of these examples of men are positively associated with the “rage” that Thomas so often refers to, further supporting the idea that rage, passion, and madness are qualities of honorable men. Throughout stanza 2, 3, 4 and 5, the author paints pictures of these men dancing, singing in the sun, and blazing like meteors. Despite the dark and dismal tone of the piece, the imagery used depicts life as joyous and lively. However, a juxtaposition still exists between men who are truly living, and men who are simply avoiding death. Words like burn, rave, sad, and rage are used when referencing those who are facing death, while words such as blaze, gay, bright, and night are used when referencing the prime of one’s life. None of these words are give the feeling of peace; however those alluding to life are far more cheerful. Although the author rarely uses the words “life” and “death”, the text symbolizes them through light and night. The contrast between the authors interpretation of life versus death is drastically different. Thomas wants the reader to see that no matter how old they become, there is always something to strive for and fight for, and to accept death would be to deprive the world of what you have to offer.

In this poem Dylan Thomas juggles the complicated concept of mortality. Thomas perfectly portrays the fight against time as we age, as well as the fear and desperation that many often feel when facing the loss of a loved one. Although the fight against death cannot be won, in “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night” Dylan Thomas emphasizes how despite this indisputable fact, one should still fight against death with all their might. Through the use of literary devices such as oxymorons and repetition, Thomas inspires readers to persevere, even in the most dire circumstances.

Teacher Takeaways

“One of my favorite things about this essay is that the student doesn’t only consider what the poem means, but how it means: they explore the way that the language both carries and creates the message. I notice this especially when the student is talking about the villanelle form, alliteration, and oxymorons. That said, I think that the student’s analysis would be more coherent if they foregrounded the main insight—that death and dying are different—in their thesis, then tracked that insight throughout the analysis. In other words, the essay has chosen evidence (parts) well but does not synthesize that evidence into a clear interpretation (whole).”– Professor Dawson

Works Cited

Thomas, Dylan. “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night.” The Norton Introduction to Literature, edited by Kelly J. Mays, portable 12th ed., W. W. Norton & Company, 2015, pp. 659.

Christ Like2

In Raymond Carver’s “Cathedral”, the character Robert plays a Christ-like role. To mirror that, the narrator plays the role of Saul, a man who despised and attacked Christ and his followers until he became converted. Throughout the story there are multiple instances where Robert does things similar to miracles performed in biblical stories, and the narrator continues to doubt and judge him. Despite Robert making efforts to converse with the narrator, he refuses to look past the oddity of his blindness. The author also pays close attention to eyes and blindness. To quote the Bible, “Having eyes, see ye not?” (King James Bible, Mark, 8.18). The characters who have sight don’t see as much as Robert, and he is able to open their eyes and hearts.

When Robert is first brought up, it is as a story. The narrator has heard of him and how wonderful he is, but has strong doubts about the legitimacy of it all. He shares a specific instance in which Robert asked to touch his wife’s face. He says, “She told me he touched his fingers to every part of her face, her nose—even her neck!”, and goes on to talk about how she tried to write a poem about it (Carver 34). The experience mentioned resembled the story of Jesus healing a blind man by putting his hands on his eyes and how, afterward, the man was restored (Mark 8.21-26). While sharing the story, however, the only thing the narrator cares about is that the blind man touched his wife’s neck. At this point in the story the narrator still only cares about what’s right in front of him, so hearing retellings means nothing to him.

When Saul is introduced in the Bible, it is as a man who spent his time persecuting the followers of Christ and “made havoc of the church” (Acts 8.3-5). From the very beginning of the story, the narrator makes it known that, “A blind man in my house was not something that I looked forward to” (Carver 34). He can’t stand the idea of something he’d only seen in movies and heard tell of becoming something real. Even when talking about his own wife, he disregards the poem she wrote for him. When he hears the name of Robert’s deceased wife, his first response is to point out how strange it sounds (Carver 36). He despises Robert, so he takes out his aggression on the people who don’t, and drives them away.

The narrator’s wife drives to the train station to pick up Robert while he stays home and waits, blaming Robert for his boredom. When they finally do arrive, the first thing he notices about Robert is his beard. It might be a stretch to call this a biblical parallel since a lot of people have beards, but Carver makes a big deal out of this detail. The next thing the narrator points out, though, is that his wife “had this blind man by his coat sleeve” (Carver 37). This draws the parallel to another biblical story. In this story a woman who has been suffering from a disease sees Jesus and says to herself, “If I may but touch his garment I shall be whole” (Matt. 9.21). Before they had gotten in the house the narrator’s wife had Robert by the arm, but even after they were at the front porch, she still wanted to hold onto his sleeve.

The narrator continues to make observations about Robert when he first sees him. One that stood out was when he was talking more about Robert’s physicality, saying he had “stooped shoulders, as if he carried a great weight there” (Carver 38). There are many instances in the Bible where Jesus is depicted carrying some type of heavy burden, like a lost sheep, the sins of the world, and even his own cross. He also points out on multiple occasions that Robert has a big and booming voice, which resembles a lot of depictions of a voice “from on high.”

After they sit and talk for a while, they have dinner. This dinner resembles the last supper, especially when the narrator says, “We ate like there was no tomorrow” (Carver 39). He also describes how Robert eats and says “he’d tear of a hunk of buttered bread and eat that. He’d follow this up with a big drink of milk” (Carver 39). Those aren’t the only things he ate, but the order in which he ate the bread and took a drink is the same order as the sacrament, a ritual created at the last supper. The author writing it in that order, despite it being irrelevant to the story, is another parallel that seems oddly specific in an otherwise normal sequence of events. What happens after the dinner follows the progression of the Bible as well.

After they’ve eaten a meal like it was their last the narrator’s wife falls asleep like Jesus’ apostles outside the garden of Gethsemane. In the Bible, the garden of Gethsemane is where Jesus goes after creating the sacrament and takes on the sins of all the world. He tells his apostles to keep watch outside the garden, but they fall asleep and leave him to be captured by the non-believers (Matt. 26.36-40). In “Cathedral,” Robert is left high and alone with the narrator when the woman who holds him in such high regard falls asleep. Instead of being taken prisoner, however, Robert turns the tables and puts all focus on the narrator. His talking to the narrator is like a metaphorical taking on of his sins. On page 46 the narrator tries to explain to him what a cathedral looks like. It turns out to be of no use, since the narrator has never talked to a blind person before, much like a person trying to pray who never has before. Robert decides he needs to place his hands on the narrator like he did to his wife on the first page.

When Saul becomes converted, it is when Jesus speaks to him as a voice “from on high.” As soon as the narrator begins drawing with Robert (a man who is high), his eyes open up. When Jesus speaks to Saul, he can no longer see. During the drawing of the cathedral, Robert asks the narrator to close his eyes. Even when Robert tells him he can open his eyes, the narrator decides to keep them closed. He went from thinking Robert coming over was a stupid idea to being a full believer in him. He says, “I put in windows with arches. I drew flying buttresses. I hung great doors. I couldn’t stop” (Carver 45). Even with all the harsh things the narrator said about Robert, being touched by him made his heart open up. Carver ends the story after the cathedral has been drawn and has the narrator say, “It’s really something” (Carver 46).

Robert acts as a miracle worker, not only to the narrator’s wife, but to him as well. Despite the difficult personality, the narrator can’t help but be converted. He says how resistant he is to have him over, and tries to avoid any conversation with him. He pokes fun at little details about him, disregards peoples’ love for him, but still can’t help being converted by him. Robert’s booming voice carries power over the narrator, but his soft touch is what finally makes him see.

Teacher Takeaways

“This author has put together a convincing and well-informed essay; a reader who lacks the same religious knowledge (like me) would enjoy this essay because it illuminates something they didn’t already realize about ‘Cathedral.’ The author has selected strong evidence from both the short story and the Bible. I would advise the student to work on structure, perhaps starting off by drafting topic-transition sentences for the beginning of each paragraph. I would also encourage them to work on sentence-level fluff. For example, ‘Throughout the story there are multiple instances where Robert does things similar to miracles performed in biblical stories’ could easily be reduced to ‘Robert’s actions in the story are reminiscent of Biblical miracles.’ It’s easiest to catch this kind of fluff when you read your draft out loud.”– Professor Wilhjelm

Works Cited

Carver, Raymond. “Cathedral.” The Norton Introduction to Literature, Portable 12th edition, edited by Kelly J. Mays, Norton, 2017, pp. 33-46.

The Bible. Authorized King James Version, Oxford UP, 1978.

The Space Between the Racial Binary3

Toni Morrison in “Recitatif” confronts race as a social construction, where race is not biological but created from human interactions. Morrison does not disclose the race of the two main characters, Twyla and Roberta, although she does provide that one character is black and the other character is white. Morrison emphasizes intersectionality by confounding stereotypes about race through narration, setting, and allusion. We have been trained to ‘read’ race through a variety of signifers, but “Recitatif” puts those signifers at odds.

Twyla is the narrator throughout “Recitatif” where she describes the events from her own point of view. Since the story is from Twyla’s perspective, it allows the readers to characterize her and Roberta solely based on what she mentions. At the beginning of the story Twyla states that “[her] mother danced all night”, which is the main reason why Twyla is “taken to St. Bonny’s” (Morrison 139). Twyla soon finds that she will be “stuck… with a girl from a whole other race” who “never washed [her] hair and [she] smelled funny” (Morrison 139). From Twyla’s description of Roberta’s hair and scent, one could assume that Roberta is black due to the stereotype that revolves around a black individual’s hair. Later on in the story Twyla runs into Roberta at her work and describes Roberta’s hair as “so big and wild” that “[she] could hardly see her face”, which is another indicator that Roberta has Afro-textured hair (Morrison 144). Yet, when Twyla encounters Roberta at a grocery store “her huge hair was sleek” and “smooth” resembling a white woman’s hair style (Morrison 146). Roberta’s hairstyles are stereotypes that conflict with one another; one attributing to a black woman, the other to a white woman. The differences in hair texture, and style, are a result of phenotypes, not race. Phenotypes are observable traits that “result from interactions between your genes and the environment” (“What are Phenotypes?”). There is not a specific gene in the human genome that can be used to determine a person’s race. Therefore, the racial categories in society are not constructed on the genetic level, but the social. Dr. J Craig Venter states, “We all evolved in the last 100,000 years from the same small number of tribes that migrated out of Africa and colonized the world”, so it does not make sense to claim that race has evolved a specific gene and certain people inherit those specific genes (Angier). From Twyla’s narration of Roberta, Roberta can be classified into one of two racial groups based on the stereotypes ascribed to her.

Intersectionality states that people are at a disadvantage by multiple sources of oppressions, such their race and class. “Recitatif” seems to be written during the Civil Rights Era where protests against racial integration took place. This is made evident when Twyla says, “strife came to us that fall…Strife. Racial strife” (Morrison 150). According to NPR, the Supreme Court ordered school busing in 1969 and went into effect in 1973 to allow for desegregation (“Legacy”). Twyla “thought it was a good thing

until she heard it was a bad thing”, while Roberta picketed outside “the school they were trying to integrate” (Morrison 150). Twyla and Roberta both become irritated with one another’s reaction to the school busing order, but what woman is on which side? Roberta seems to be a white woman against integrating black students into her children’s school, and Twyla suggests that she is a black mother who simply wants best for her son Joseph even if that does mean going to a school that is “far-out-of-the-way” (Morrison 150). At this point in the story Roberta lives in “Annandale” which is “a neighborhood full of doctors and IBM executives” (Morrison 147), and at the same time, Twyla is “Mrs. Benson” living in “Newburgh” where “half the population… is on welfare…” (Morrison 145). Twyla implies that Newburgh is being gentrified by these “smart IBM people”, which inevitably results in an increase in rent and property values, as well as changes the area’s culture. In America, minorities are usually the individuals who are displaced and taken over by wealthier, middle-class white individuals. From Twyla’s tone, and the setting, it seems that Twyla is a black individual that is angry towards “the rich IBM crowd” (Morrison 146). When Twyla and Roberta are bickering over school busing, Roberta claims that America “is a free country” and she is not “doing anything” to Twyla (Morrison 150). From Roberta’s statements, it suggests that she is a affluent, and ignorant white person that is oblivious to the hardships that African Americans had to overcome, and still face today. Rhonda Soto contends that “Discussing race without including class analysis is like watching a bird fly without looking at the sky…”. It is ingrained in America as the normative that whites are mostly part of the middle-class and upper-class, while blacks are part of the working-class. Black individuals are being classified as low-income based entirely on their skin color. It is pronounced that Twyla is being discriminated against because she is a black woman, living in a low-income neighborhood where she lacks basic resources. For example, when Twyla and Roberta become hostile with one another over school busing, the supposedly white mothers start moving towards Twyla’s car to harass her. She points out that “[my] face[ ] looked mean to them” and that these mothers “could not wait to throw themselves in front of a police car” (Morrison 151). Twyla is indicating that these mothers are privileged based on their skin color, while she had to wait until her car started to rock back and forth to a point where “the four policeman who had been drinking Tab in their car finally got the message and [then] strolled over” (Morrison 151). This shows that Roberta and the mothers protesting are white, while Twyla is a black woman fighting for her resources. Not only is Twyla being targeted due to her race, but as well her class by protesting mothers who have classified her based on intersectionality.

Intersectionality is also alluded in “Recitatif” based on Roberta’s interests. Twyla confronts Roberta at the “Howard Johnson’s” while working as a waitress with her “blue and white triangle on [her] head” and “[her] hair shapeless in a net” (Morrison 145). Roberta boasts that her friend has “an appointment with Hendrix” and shames Twyla for not knowing Jimi Hendrix (Morrison 145). Roberta begins to explain that “he’s only the biggest” rockstar, guitarist, or whatever Roberta was going to say. It is clear that Roberta is infatuated with Jimi Hendrix, who was an African American rock guitarist. Because Jimi Hendrix is a black musician, the reader could assume that Roberta is also black. At the same time, Roberta may be white since Jimi Hendrix appealed to a plethora of people. In addition, Twyla illustrates when she saw Roberta “sitting in [the] booth” she was “with two guys smothered in head and facial” (Morrison 144). These men may be two white counter culturists, and possible polygamists, in a relationship with Roberta who is also a white. From Roberta’s enthusiasm in Jimi Hendrix it alludes that she may be black or white, and categorized from this interest.

Intersectionality states that people are prone to “predict an individual’s identity, beliefs, or values based on categories like race” (Williams). Morrison chose not to disclose the race of Twyla and Roberta to allow the reader to make conclusions about the two women based on the vague stereotypes Morrison presented throughout “Recitatif”. Narration, setting, and allusion helped make intersectionality apparent, which in turn allowed the readers understand, or see, that race is in fact a social construction. “Recitatif” forces the readers to come to terms with their own racial prejudices.

Teacher Takeaways

“This essay is a good companion to the same author’s summary essay, ‘Maggie as the Focal Point.’ It has a detailed thesis (the last two sentences of the first paragraph) that give me an idea of the author’s argument and the structure they plan to follow in the essay. This is a good example of the T3 strategy and consequent organization. That said, because this student used the three-part thesis and five-paragraph essay that it encourages, each paragraph is long and dense. I would encourage this student to break up those units into smaller, more digestable pieces, perhaps trying to divide the vague topics (‘narration, setting, and allusion’) into more specific subtopics.”– Professor Wilhjelm

Works Cited

Angier, Natalie. “Do Races Differ? Not Really, DNA Shows.” The New York Times, 22 Aug. 2000, archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/library/national/science/082200sci-genetics-race.html.

Morrison, Toni. “Recitatif.” The Norton Introduction to Literature. Portable 12th edition, edited by Kelly J. Mays, W.W. Norton & Company, 2017, pp. 483+.

“The Legacy of School Busing.” NPR, 30 Apr. 2004, https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=1853532.

Soto, Rhonda. “Race and Class: Taking Action at the Intersections.” Association of American Colleges & Universities, 1 June 2015, www.aacu.org/diversitydemocracy/2008/fall/soto.

Williams, Steve. “What Is Intersectionality, and Why Is It Important?” Care2, https://www.aaup.org/article/what-intersectionality-and-why-it-important#.X4owl_lKiUk.

“What Are Phenotypes?” 23andMe, www.23andme.com/gen101/phenotype/.