Appendix C: Metacognition

Glaciers are known for their magnificently slow movement. To the naked eye, they appear to be giant sheets of ice; however, when observed over long periods of time, we can tell that they are actually rivers made of ice.1

Despite their pace, though, glaciers are immensely powerful. You couldn’t notice in the span of your own lifetime, but glaciers carve out deep valleys (like the one to the right) and grind the earth down to bedrock.2 Massive changes to the landscape and ecosystem take place over hundreds of thousands of years, making them difficult to observe from a human vantage point.

However, humans too are always changing, even within our brief lifetimes. No matter how stable our sense of self, we are constantly in a state of flux, perpetually changing as a result of our experiences and our context. Like with glaciers, we can observe change with the benefit of time; on the other hand, we might not perceive the specific ways in which we grow on a daily basis. When change is gradual, it is easy to overlook.

Particularly after challenging learning experiences, like those embraced by this textbook, it is crucial that you reflect on the impact those challenges had on your knowledge or skillsets, your worldviews, and your relationships.

Throughout your studies, I encourage you to occasionally pause to evaluate your progress, set new goals, and cement your recent learning. If nothing else, take 10 minutes once a month to free-write about where you were, where you are, and where you hope to be.

You may recognize some of these ideas from Chapter 3: indeed, what I’m talking about is the rhetorical gesture of reflection. Reflection is “looking back in order to look forward,” a way of peering back through time to draw insight from an experience that will support you (and your audience) as you move into the future.

I would like to apply this concept in a different context, though: instead of reflecting on an experience that you have narrated, as you may have in Section 1, you will reflect on the progress you’ve made as a critical consumer and producer of rhetoric through a metacognitive reflection.

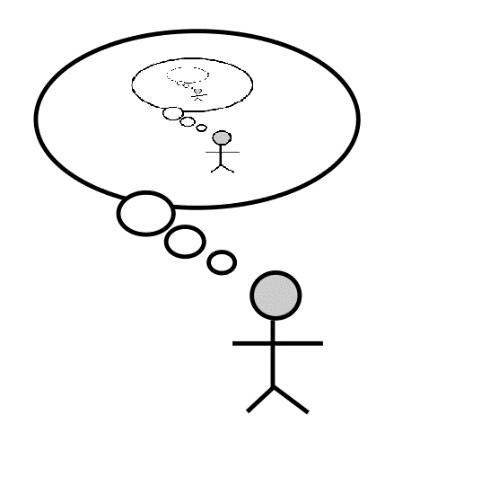

Simply put, metacognition means “thinking about thinking.” For our purposes, though, metacognition means thinking about how thinking evolves. Reflection on your growth as a writer requires you to evaluate how your cognitive and rhetorical approaches have changed.

In this context, your metacognitive reflection can evaluate two distinct components of your learning:

- Concepts that have impacted you: New ideas or approaches to rhetoric or writing that have impacted the way you write, read, think, or understanding of the world.

Ex: Radical Noticing, Inquiry-Based Research

- Skills that have impacted you: Specific actions or techniques you can apply to your writing, reading, thinking, or understanding of the world.

Ex: Reverse Outlining, Imagery Inventory

Of course, because we are “looking back in order to look forward,” the concepts and skills that you identify should support a discussion of how those concepts and skills will impact your future with rhetoric, writing, the writing process, or thinking processes. Your progress to this point is important, but it should enable even more progress in the future.

Chapter Vocabulary

|

Vocabulary |

Definition |

|

literally, “thinking about thinking.” May also include how thinking evolves and reflection on growth. |

|

Metacognitive Activities

There are a variety of ways to practice metacognition. The following activities will help you generate ideas for a metacognitive reflection. Additionally, though, a highly productive means of evaluating growth is to look back through work from earlier in your learning experience. Drafts, assignments, and notes documented your skills and understanding at a certain point in time, preserving an earlier version of you to contrast with your current position and abilities, like artifacts in a museum. In addition to the following activities, you should compare your current knowledge and skills to your previous efforts.

Writing Home from Camp

For this activity, you should write a letter to someone who is not affiliated with your learning community: a friend or family member who has nothing to do with your class or study of writing. Because they haven’t been in this course with you, imagine they

don’t know anything about what we’ve studied.

Your purpose in the letter is to summarize your learning for an audience unfamiliar with the guiding concepts or skills encountered in your writing class. Try to boil down your class procedures, your own accomplishments, important ideas, memorable experiences, and so on.

Metacognitive Interview

With one or two partners, you will conduct an interview to generate ideas for your metacognitive reflection. You can also complete this activity independently, but there are a number of advantages to working collaboratively: your partner(s) may have ideas that you hadn’t thought of; you may find it easier to think out loud than on paper; and you will realize that many of your challenges have been shared.

During this exercise, one person should interview another, writing down answers while the interviewee speaks aloud. Although the interviewer can ask clarifying questions, the interviewee should talk most. For each question, the interviewee should speak for 1-2 minutes. Then, for after 1-2 minutes, switch roles and respond to the same question. Alternate the role of interviewer and interviewee for each question such that every member gets 1-2 minutes to respond while the other member(s) takes notes.

After completing all of the questions, independently free-write for five minutes. You can make note of recurring themes, identify surprising ideas, and fill in responses that you didn’t think of at the time.

- What accomplishments are you proud of from this term—in this class, another class, or your non-academic life?

- What activities, assignments, or experiences from this course have been most memorable for you? Most important?

- What has surprised you this term—in a good way or a bad way?

- Which people in your learning community have been most helpful, supportive, or respectful?

- Has your perspective on writing, research, revision, (self-)education, or critical thinking changed this term? How so?

- What advice would you give to the beginning-of-the-term version of yourself?

Model Texts by Student Authors

Model Metacognitive Reflection 13

I somehow ended up putting off taking this class until the very end of my college career. Thus, coming into it I figured that it would be a breeze because I’d already spent the past four years writing and refining my skills. What I quickly realized is that these skills have become extremely narrow; specifically focused in psychological research papers. Going through this class has truly equipped me with the skills to be a better, more organized, and more diverse writer.

I feel that the idea generation and revision exercises that we did were most beneficial to my growth as a writer. Generally, when I have a paper that I have to write, I anxiously attempt to come up with things that I could write about in my head. I also organize said ideas into papers in my head; rarely conceptualizing them on paper. Instead I just come up with an idea in my head, think about how I’m going to write it, then I sit down and dive straight into the writing. Taking the time to really generate various ideas and free write about them not only made me realize how much I have to write about, but also helped me to choose the best topic for the paper that I had to write. I’m sure that there have been many times in the past when I have simply written a paper on the first idea that came to my mind when I likely could have written a better paper on something else if I really took the time to flesh different ideas out.

Sharing my thoughts, ideas, and writings with my peers and with you have been a truly rewarding experience. I realized through this process that I frequently assume my ideas aren’t my comfort zone in this class and forced myself to present the ideas that I really wanted to talk about, even though I felt they weren’t all that interesting. What I came to experience is that people were really interested in what I had to say and the topics in which I chose to speak about were both important and interesting. This class has made me realize how truly vulnerable the writing process is.

This class has equipped me with the skills to listen to my head and my heart when it comes to what I want to write about, but to also take time to generate multiple ideas. Further, I have realized the important of both personal and peer revision in the writing process. I’ve learned the importance of stepping away from a paper that you’ve been staring at for hours and that people generally admire vulnerability in writing.

Model Metacognitive Reflection 24

I entered class this term having written virtually nothing but short correspondence or technical documents for years. While I may have a decent grasp of grammar, reading anything I wrote was a slog. This class has helped me identify specific problems to improve my own writing and redefine writing as a worthwhile process and study tool rather than just a product. It has also helped me see ulterior motives of a piece of writing to better judge a source or see intended manipulation.

This focus on communication and revision over perfection was an awakening for me. As I’ve been writing structured documents for years, I’ve been focusing on structure and grammatical correctness over creating interesting content or brainstorming and exploring new ideas. Our class discussions and the article “Shitty First Drafts” have taught me that writing is a process, not a product. The act of putting pen to paper and letting ideas flow out has value in itself, and while those ideas can be organized later for a product they should first be allowed to wander and be played with.

Another technique I first encountered in this class was that of the annotated bibliography. Initially this seemed only like extra work that may prove useful to a reader or a grader. After diving further into my own research however, it was an invaluable reference to organize my sources and guide the research itself. Not only did it provide a paraphrased library of my research, it also shined light on patterns in my sources that I would not have noticed otherwise. I’ve already started keeping my own paraphrased notes along with sources in other classes, and storing my sources together to maintain a personal library.

People also say my writing is dry, but I could never pin down the problem they were driving at. This class was my first exposure to the terms logos, ethos, and pathos, and being able to name and identify different styles of argumentation helped me realize that I almost exclusively use logos in my own writing. Awareness of these styles let me contrast my own writing with how extensively used paths and ethos are in most nonfiction writing found in books and news articles. I’ve noticed how providing example stories or posing questions can keep readers engaged while meaningfully introducing sources in the text, rather than as a parenthetical aside, improves the flow of writing and helps statements land with more authority.

As for narrative writing, I found the Global Revision Exercise for the first essay particularly interesting. To take a piece of writing and intentionally force a different voice or perspective on it showed how I can take improve a boring part of my paper by using a unique voice or style. This could be useful for expanding on reflective sections to evoke a particular feeling in the reader, or in conjunction with the Image Building Exercise to pull the reader into a specific moment.

This class was a requirement for me from which I didn’t expect to gain much. English classes I have taken in the past focused on formulaic writing and grammar or vague literary analysis, and I expected more of the same. Ultimately, I was pleasantly surprised by the techniques covered which are immediately applicable in other classes and more concrete analysis of rhetoric which made the vague ideas touched on before reach a more tangible clarity.

Endnotes

literally, “thinking about thinking.” May also include how thinking evolves and reflection on growth.