Appendix B: Engaged Reading Strategies

There are a lot of ways to become a better writer, but the best way I know is to read a lot. Why? Not only does attentive reading help you understand grammar and mechanics more intuitively, but it also allows you to develop your personal voice and critical worldviews more deliberately. By encountering a diversity of styles, voices, and perspectives, you are likely to identify the ideas and techniques that resonate with you; while your voice is distinctly yours, it is also a unique synthesis of all the other voices you’ve been exposed to.

But it is important to acknowledge that the way we read matters. At some point in your academic career, you’ve probably encountered the terms “active reading” or “critical reading.” But what exactly does active reading entail?

It begins with an acknowledgment that reading, like writing, is a process: active reading is complex, iterative, and recursive, consisting of a variety of different cognitive actions. Furthermore, we must recognize that the reading process can be approached many different ways, based on our backgrounds, strengths, and purposes.

However, many people don’t realize that there’s more than one way to read; our early training as readers fosters a very narrow vision of critical literacy. For many generations in many cultures across the world, developing reading ability has generally trended toward efficiency and comprehension of main ideas. Your family, teachers, and other folks who taught you to read trained you to read in particular ways. Most often, novice readers are encouraged to ignore detail and nuance in the name of focus: details are distracting. Those readers also tend to project their assumptions on a text. This practice, while useful for global understanding of a text, is only one way to approach reading; by itself, it does not constitute “engaged reading.”

In her landmark article on close reading, Jane Gallop explains that ignoring details while reading is effective, but also problematic:

When the reader concentrates on the familiar, she is reassured that what she already knows is sufficient in relation to this new book. Focusing on the surprising, on the other hand, would mean giving up the comfort of the familiar, of the already known for the sake of learning, of encountering something new, something she didn’t already know.

In fact, this all has to do with learning. Learning is very difficult; it takes a lot of effort. It is of course much easier if once we learn something we can apply what we have learned again and again. It is much more difficult if every time we confront something new, we have to learn something new.

Reading what one expects to find means finding what one already knows. Learning, on the other hand, means coming to know something one did not know before. Projecting is the opposite of learning. As long as we project onto a text, we cannot learn from it, we can only find what we already know. Close reading is thus a technique to make us learn, to make us see what we don’t already know, rather than transforming the new into the old.1

To be engaged readers, we must avoid projecting our preconceived notions onto a text. To achieve deep, complex understanding, we must consciously attend to a text using a variety of strategies.

The following strategies are implemented by all kinds of critical readers; some readers even use a combination of these strategies. Like the writing process, though, active reading looks different for everyone. These strategies work really well for some people, but not for others: I encourage you to experiment with them, as well as others not covered here, to figure out what your ideal critical reading process looks like.

Chapter Vocabulary

|

Vocabulary |

Definition |

|

engaged reading strategy by which a reader marks up a text with their notes, questions, new vocabulary, ideas, and emphases. |

|

|

also referred to in this text as engaged reading, a set of strategies and concepts to interrupt projection and focus on a text. |

|

|

an engaged reading strategy to improve comprehension and interrupt projection. Survey, Question, Read, Recite, Review. |

|

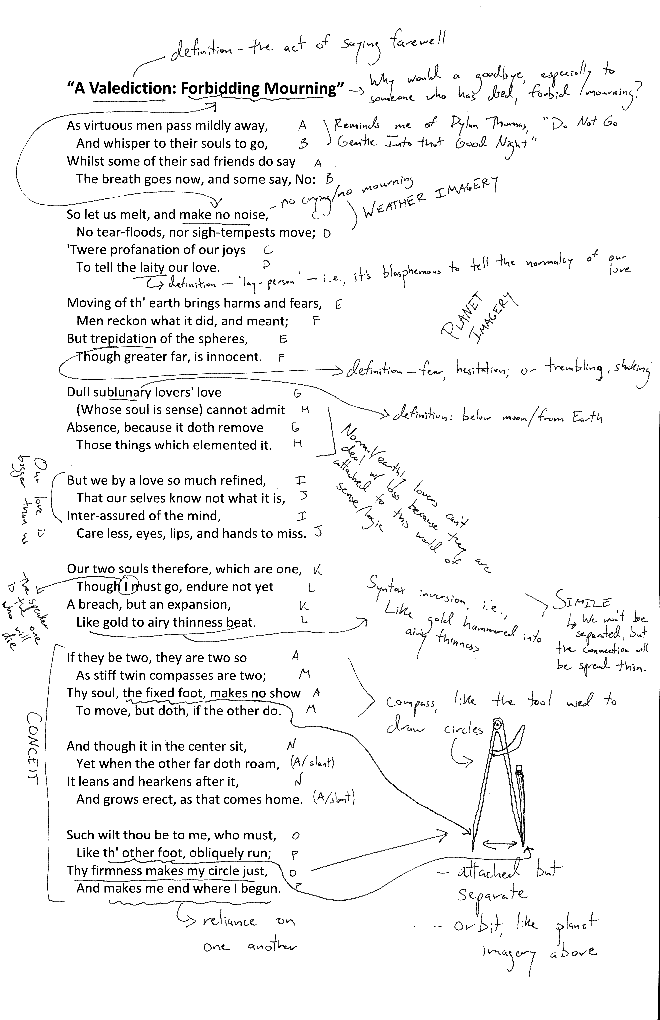

Annotation

Annotation

Annotation is the most common and one of the most useful engaged reading strategies. You might know it better as “marking up” a text. Annotating a reading is visual evidence to your teacher that you read something—but more importantly, it allows you to focus on the text itself by asking questions and making notes to yourself to spark your memory later.

Take a look at the sample annotation on the next page. Note that the reader here is doing several different things:

- Underlining important words, phrases, and sentences. Many studies have shown that underlining or highlighting alone does not improve comprehension or recall; however, limited underlining can draw your eye back to curious phrases as you re-read, discuss, or analyze a text.

- Writing marginal notes. Even though you can’t fit complex ideas in the margins, you can:

- use keywords to spark your memory,

- track your reactions,

- remind yourself where an important argument is,

- define unfamiliar words,

- draw illustrations to think through an image or idea visually, or

- make connections to other texts.

In addition to taking notes directly on the text itself, you might also write a brief summary with any white space left on the page. As we learned in Chapter Two, summarizing will help you process information, ensure that you understand what you’ve read, and make choices about which elements of the text to focus on.

For a more guided process for annotating an argument, follow these steps from Brian Gazaille,2 a teacher at University of Oregon:

Most “kits” that you find in novelty stores give you materials and instructions about how to construct an object: a model plane, a bicycle, a dollhouse. This kit asks you to deconstruct one of our readings, identifying its thesis, breaking down its argument, and calling attention to the ways it supports its ideas. Dissecting a text is no easy task, and this assignment is designed to help you understand the logic and rhetoric behind what you just read.

Print out a clean copy of the text and annotate it as follows:

- With a black pen, underline the writer’s thesis. If you think the thesis occurs over several sentences, underline all of them. If you think the text has an implicit (present but unstated) thesis, underline the section that comes closest to being the thesis and rewrite it as a thesis in the margins of the paper.

- With a different color pen, underline the “steps” of the argument. In the margins of the paper, paraphrase those steps and say whether or not you agree with them. To figure out the steps of the argument, ask: What was the author’s thesis? What ideas did they need to talk about to support that thesis? Where and how does each paragraph discuss those ideas? Do you agree with those ideas?

- With a different color pen, put [brackets] around any key terms or difficult concepts that the author uses, and define those terms in the margins of the paper.

- With a different color pen, describe the writer’s persona at the top of the first page. What kind of person is “speaking” the essay? What kind of expertise do they have? What kind of vocabulary do they use? How do they treat their intended audiences, or what do they assume about you, the reader?

- Using a highlighter, identify any rhetorical appeals (logos, pathos, ethos). In the margins, explain how the passage works as an appeal. Ask: What is the passage asking you to buy into? How does it prompt me to reason (logos), feel (pathos), or believe (ethos)?

- At the end of the text, and in any color pen, write any questions or comments or questions you have for the author. What strikes you as interesting/odd/infuriating/ insightful about the argument? Why? What do you think the author has yet to discuss, either unconsciously or purposely?

For a more guided process for annotating a short story or memoir, follow these steps from Brian Gazaille,3 a teacher at University of Oregon:

Most “kits” that you find in novelty stores give you materials and instructions about how to construct an object: a model plane, a bicycle, a dollhouse. This kit asks you to deconstruct one of our readings, identifying its thesis, breaking down its argument, and calling attention to the ways it supports its ideas. Dissecting a text is no easy task, and this assignment is designed to help you understand the logic and rhetoric behind what you just read.

Print out a clean copy of the text and annotate it as follows:

- In one color, chart the story’s plot. Identify these elements in the margins of the text by writing the appropriate term next to the corresponding part[s] of the story. (Alternatively, draw a chart on a separate piece of paper.) Your plot chart must include the following terms: exposition, rising action, crisis, climax, falling action, dénouement.

- At the top of the first page, identify the story’s point of view as fully as possible. (Who is telling the story? What kind of narration is given?) In the margins, identify any sections of text in which the narrator’s position/intrusion becomes significant.

- Identify your story’s protagonist and highlight sections of text that supply character description or motivation, labeling them in the margins. In a different color, do the same for the antagonist(s) of the story.

- Highlight (in a different color) sections of the text that describe the story’s setting. Remember, this can include place, time, weather, and atmosphere. Briefly discuss the significance of the setting, where appropriate.

- With a different color, identify key uses of figurative language—metaphors, similes, and personifications—by [bracketing] that section of text and writing the appropriate term.

- In the margins, identify two distinctive lexicons (“word themes” or kinds of vocabulary) at work in your story. Highlight (with new colors) instances of those lexicons.

- Annotate the story with any comments or questions you have. What strikes you as interesting? Odd? Why? What makes you want to talk back? Does any part of the text remind you of something else you’ve read or seen? Why?

SQ3R

This is far and away the most underrated engaged reading strategy I know: the few students I’ve had who know about it swear by it.

The SQ3R (or SQRRR) strategy has five steps:

Before Reading:

Survey (or Skim): Get a general idea of the text to prime your brain for new information. Look over the entire text, keeping an eye out for bolded terms, section headings, the “key” thesis or argument, and other elements that jump out at you. An efficient and effective way to skim is by looking at the first and last sentences of each paragraph.

While Reading:

Question: After a quick overview, bring yourself into curiosity mode by developing a few questions about the text. Developing questions is a good way to keep yourself engaged, and it will guide your reading as you proceed.

- What do you anticipate about the ideas contained in the text?

- What sort of biases or preoccupations do you think the text will reflect?

Read: Next, you should read the text closely and thoroughly, using other engaged reading strategies you’ve learned.

- Annotate the text: underline/highlight important passages and make notes to yourself in the margins.

- Record vocabulary words you don’t recognize.

- Pause every few paragraphs to check in with yourself and make sure you’re confident about what you just read.

- Take notes on a separate page as you see fit.

Recite: As you’re reading, take small breaks to talk to yourself aloud about the ideas and information you’re processing. I know this seems childish, but self-talk is actually really important and really effective. (It’s only as adolescents that we develop this aversion to talking to ourselves because it’s frowned upon socially.) If you feel uncomfortable talking to yourself, try to find a willing second party—a friend, roommate, classmate, significant other, family member, etc.—who will listen. If you have a classmate with the same reading assignment, practice this strategy collaboratively!

After Reading:

Review: When you’re finished reading, spend a few minutes “wading” back through the text: not diving back in and re-reading, but getting ankle-deep to refresh yourself. Reflect on the ideas the text considered, information that surprised you, the questions that remain unanswered or new questions you have, and the text’s potential use-value. The Cornell note-taking system recommends that you write a brief summary, but you can also free-write or talk through the main points that you remember. If you’re working with a classmate, try verbally summarizing.

Double-Column Notes

|

Notes & Quotes |

Questions & Reactions |

|

|

|

This note-taking strategy seems very simple at first pass, but will help keep you organized as you interact with a reading.

Divide a clean sheet of paper into two columns; on the left, make a heading for “Notes and Quotes,” and on the right, “Questions and Reactions.” As you read and re-read, jot down important ideas and words from the text on the left, and record your intellectual and emotional reactions on the right. Be sure to ask prodding questions of the text along the way, too!

By utilizing both columns, you are reminding yourself to stay close to the text (left side) while also evaluating how that text acts on you (right side). This method strengthens the connection you build with a reading.

Increasing Reading Efficiency

Although reading speed is not the most important part of reading, we often find ourselves with too much to read and too little time. Especially when you’re working on an inquiry-based research project, you’ll encounter more texts than you could possibly have time to read thoroughly. Here are a few quick tips:

Encountering an Article in a Hurry:

- Some articles, especially scholarly articles, have abstracts. An abstract is typically an overview of the discussion, interests, and findings of an article; it’s a lot like a summary. Using the abstract, you can get a rough idea of the contents of an article and determine whether it’s worth reading more closely.

- Some articles will have a conclusion set off at the end of the article. Often, these conclusions will summarize the text and its main priorities. You can read the conclusion before reading the rest of the article to see if its final destination is compatible with yours.

- If you’re working on a computer with search-enabled article PDFs, webpages, or documents, use the “Find” function (Ctrl + F on a PC and ⌘ + F on a Mac) to locate keywords. It’s possible that you know what you’re looking for: use technology to get you there faster.

Encountering a Book in a Hurry:

Although print books are more difficult to speed-read, they are very valuable resources for a variety of reading and writing situations. To get a broad idea of a book’s contents, try the following steps:

- Check the Table of Contents and the Index. At the front and back of the book, respectively, these resources provide more key terms, ideas, and topics that may or may not seem relevant to your study.

- If you’ve found something of interest in the Table of Contents and/or Index, turn to the chapter/section of interest. Read the first paragraph, the (approximate) middle two to three paragraphs, and the last paragraph. Anything catch your eye? (If not, it may be worth moving on.)

- If the book has an introduction, read it: many books will develop their focus and conceptual frameworks in this section, allowing you to determine whether the text will be valuable for your purposes.

Finally, check out “5 Ways to Read Faster That ACTUALLY Work – College Info Geek” [Video] that has both practical tips to increase reading speed and conceptual reminders about the learning opportunities that reading creates.

Endnotes

engaged reading strategy by which a reader marks up a text with their notes, questions, new vocabulary, ideas, and emphases.

also referred to in this text as engaged reading, a set of strategies and concepts to interrupt projection and focus on a text.

an engaged reading strategy to improve comprehension and interrupt projection. Survey, Question, Read, Recite, Review.