11 Happiness: The Empirical Science of Happiness and the Philosophy of Tibetan Buddhism

Introduction

This chapter examines empirical science of happiness, and discusses the traditions and philosophy of Tibetan Buddhism. In recent years as happiness science has flourished, it has become apparent that some of the philosophies of Tibetan Buddhism match well with discoveries from empirical science. This chapter examines scientific findings on happiness and how these parallel ideas from Tibetan Buddhism.

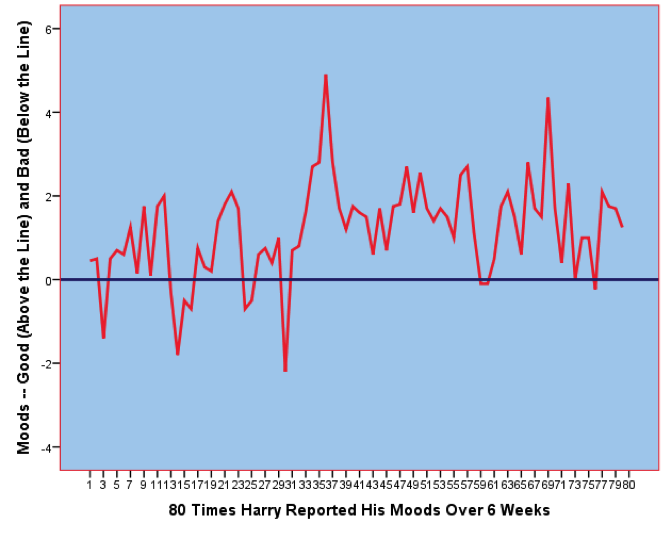

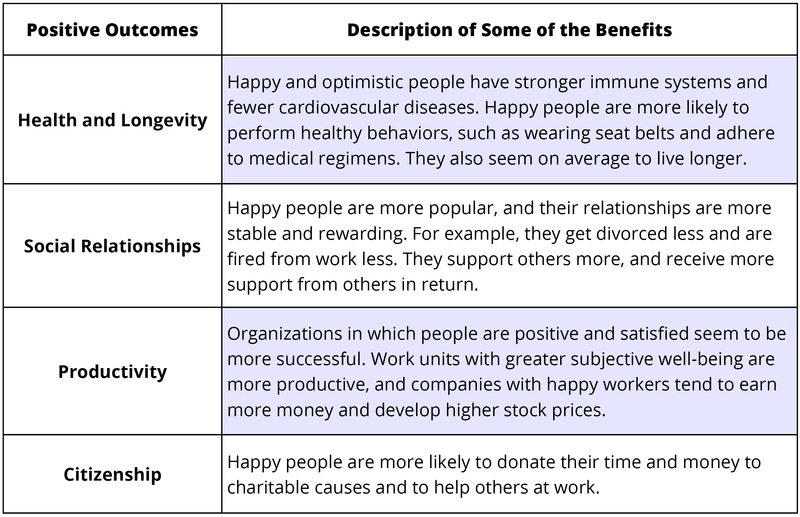

Professionals and scientists use the term Subjective well-being (SWB) as the scientific term for happiness and life satisfaction—thinking and feeling that your life is going well, not badly. Scientists rely primarily on self-report surveys to assess the happiness of individuals, but they have validated these scales with other types of measures. People’s levels of subjective well-being are influenced by both internal factors, such as personality and outlook, and external factors, such as the society in which they live. Some of the major determinants of subjective well-being are a person’s inborn temperament, the quality of their social relationships, the societies they live in, and their ability to meet their basic needs. To some degree people adapt to conditions so that over time our circumstances may not influence our happiness as much as one might predict they would. Importantly, researchers have also studied the outcomes of subjective well-being and have found that “happy” people are more likely to be healthier and live longer, to have better social relationships, and to be more productive at work. In other words, people high in subjective well-being seem to be healthier and function more effectively compared to people who are chronically stressed, depressed, or angry. Thus, happiness does not just feel good, but it is good for people and for those around them.

Tibetan Buddhism is a form of philosophy and type of Buddhism practiced by the people of Tibet, and elsewhere in the world. Tibetan Buddhism is based in the teachings of the Buddha as introduced to the country of Tibet between the 7th and 9th centuries. Guatama Buddha, also called Buddha was a Yogi and teacher living in ancient India, and did not consider himself to be superior to other people. He felt everyone could learn what he had learned. His followers, however, have so fervently held to his teachings that the practice of Buddhism is often viewed as a religion, and over time it became mixed with religious stories and myths, as people tried to fit Buddhism into their traditional culture. Buddhism, including Tibetan Buddhism, includes ceremonies, practices, and teachings designed to reduce life suffering, increase compassion, and help people find well-being even amidst difficult challenges. Buddhism has a particular focus on happiness that comes from the decisions we make about how to live our life, and the types of thoughts we think and how we regulate our emotions.

For a review of the life of the Buddha and a basic understanding of the teachings of the Buddha, students can watch the movie below created by the American television service, the Public Broadcasting Service, pbs.org (2015)

https://youtu.be/EDgd8LT9AL4

The Science of Well-Being

When people describe what they most want out of life, happiness is almost always on the list, and very frequently it is at the top of the list. When people describe what they want in life for their children, they frequently mention health and wealth, occasionally they mention fame or success—but they almost always mention happiness. People will claim that whether their kids are wealthy and work in some prestigious occupation or not, “I just want my kids to be happy.” Happiness appears to be one of the most important goals for people, if not the most important. But what is it, and how do people get it?

In this module we describe “happiness” or subjective well-being (SWB) as a process—it results from certain internal and external causes, and in turn it influences the way people behave, as well as their physiological states. Thus, high SWB is not just a pleasant outcome but having subjective well-being is an important factor in our future success. Because scientists have developed valid ways of measuring “happiness,” they have come in the past decades to know much about its causes and consequences.

Types of Happiness

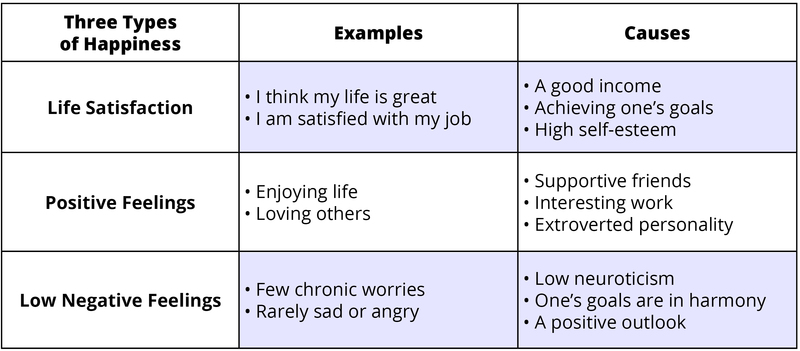

Philosophers debated the nature of happiness for thousands of years, but scientists have recently discovered that happiness means different things. Three major types of happiness are high life satisfaction, frequent positive feelings, and infrequent negative feelings (Diener, 1984). “Subjective well-being” is the label given by scientists to the various forms of happiness taken together. Although there are additional forms of SWB, the three in the table below have been studied extensively. The table also shows that the causes of the different types of happiness can be somewhat different.

You can see in the table that there are different causes of happiness, and that these causes are not identical for the various types of SWB. Therefore, there is no single key, no magic wand—high SWB is achieved by combining several different important elements (Diener & Biswas-Diener, 2008). Thus, people who promise to know the key to happiness are oversimplifying.

Some people experience all three elements of happiness—they are very satisfied, enjoy life, and have only a few worries or other unpleasant emotions. Other unfortunate people are missing all three. Most of us also know individuals who have one type of happiness but not another. For example, imagine an elderly person who is completely satisfied with her life—she has done most everything she ever wanted—but is not currently enjoying life that much because of the infirmities of age. There are others who show a different pattern, for example, who really enjoy life but also experience a lot of stress, anger, and worry. And there are those who are having fun, but who are dissatisfied and believe they are wasting their lives. Because there are several components to happiness, each with somewhat different causes, there is no magic single cure-all that creates all forms of SWB. This means that to be happy, individuals must acquire each of the different elements that cause it.

Causes of Subjective Well-Being

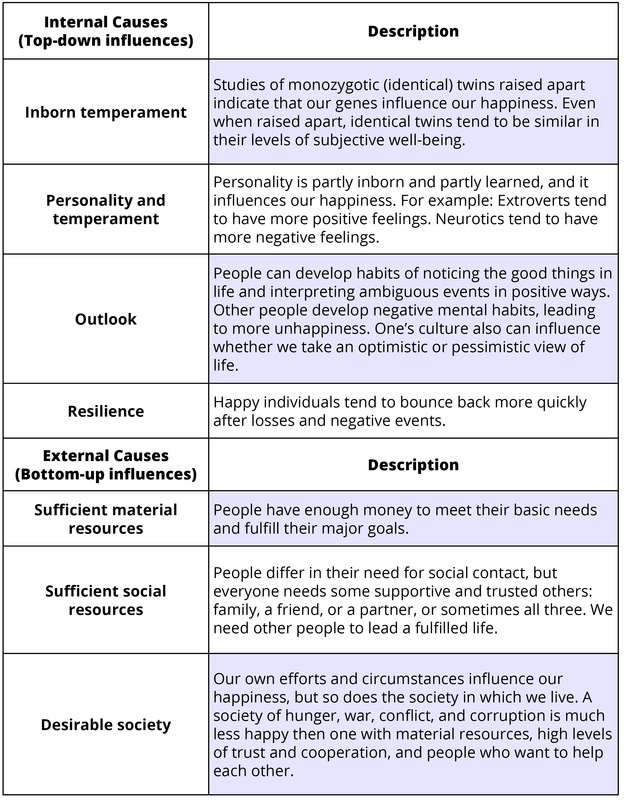

There are external influences on people’s happiness—the circumstances in which they live. It is possible for some to be happy living in poverty with ill health, or with a child who has a serious disease, but this is difficult. In contrast, it is easier to be happy if one has supportive family and friends, ample resources to meet one’s needs, and good health. But even here there are exceptions—people who are depressed and unhappy while living in excellent circumstances. Thus, people can be happy or unhappy because of their personalities and the way they think about the world or because of the external circumstances in which they live. People vary in their propensity to happiness—in their personalities and outlook—and this means that knowing their living conditions is not enough to predict happiness.

In the table below are shown internal and external circumstances that influence happiness. There are individual differences in what makes people happy, but the causes in the table are important for most people (Diener, Suh, Lucas, & Smith, 1999; Lyubomirsky, 2013; Myers, 1992).

Societal Influences on Happiness

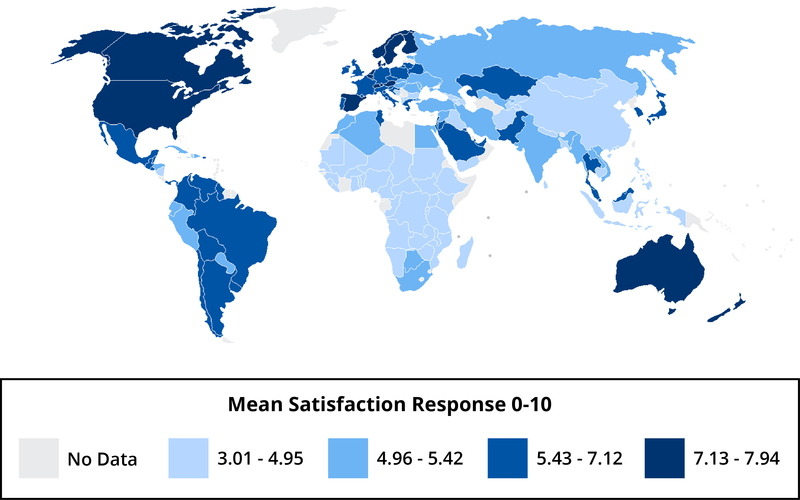

When people consider their own happiness, they tend to think of their relationships, successes and failures, and other personal factors. But a very important influence on how happy people are is the society in which they live. It is easy to forget how important societies and neighborhoods are to people’s happiness or unhappiness. In Figure 1, I present life satisfaction around the world. You can see that some nations, those with the darkest shading on the map, are high in life satisfaction. Others, the lightest shaded areas, are very low. The grey areas in the map are places we could not collect happiness data—they were just too dangerous or inaccessible.

Can you guess what might make some societies happier than others? Much of North America and Europe have relatively high life satisfaction, and much of Africa is low in life satisfaction. For life satisfaction living in an economically developed nation is helpful because when people must struggle to obtain food, shelter, and other basic necessities, they tend to be dissatisfied with lives. However, other factors, such as trusting and being able to count on others, are also crucial to the happiness within nations. Indeed, for enjoying life our relationships with others seem more important than living in a wealthy society. One factor that predicts unhappiness is conflict—individuals in nations with high internal conflict or conflict with neighboring nations tend to experience low SWB.

Money and Happiness

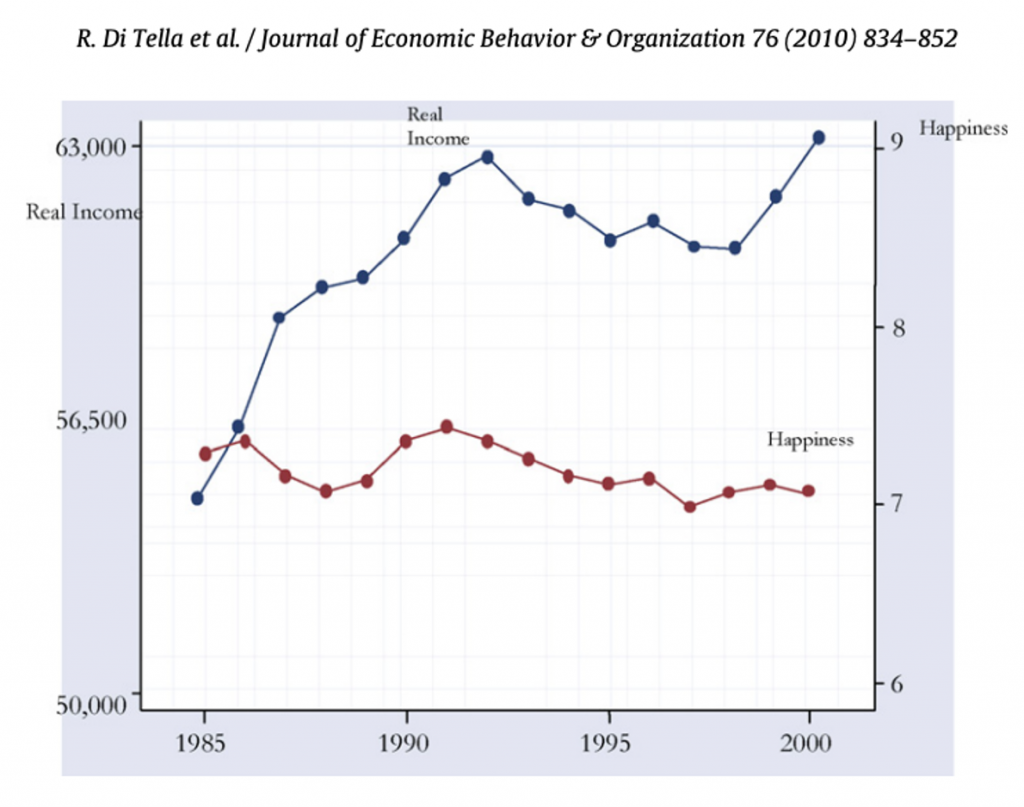

Will money make you happy? A certain level of income is needed to meet our needs, and very poor people are frequently dissatisfied with life (Diener & Seligman, 2004). However, having more and more money has diminishing returns—higher and higher incomes make less and less difference to happiness. Wealthy nations tend to have higher average life satisfaction than poor nations, but the United States has not experienced a rise in life satisfaction over the past decades, even as income has doubled. The goal is to find a level of income that you can live with and earn. Don’t let your aspirations continue to rise so that you always feel poor, no matter how much money you have. Research shows that materialistic people often tend to be less happy, and putting your emphasis on relationships and other areas of life besides just money is a wise strategy. Money can help life satisfaction, but when too many other valuable things are sacrificed to earn a lot of money—such as relationships or taking a less enjoyable job—the pursuit of money can harm happiness.

There are stories of wealthy people who are unhappy and of janitors who are very happy. For instance, a number of extremely wealthy people in South Korea have committed suicide recently, apparently brought down by stress and other negative feelings. On the other hand, there is the hospital janitor who loved her life because she felt that her work in keeping the hospital clean was so important for the patients and nurses. Some millionaires are dissatisfied because they want to be billionaires. Conversely, some people with ordinary incomes are quite happy because they have learned to live within their means and enjoy the less expensive things in life.

It is important to always keep in mind that high materialism seems to lower life satisfaction—valuing money over other things such as relationships can make us dissatisfied. When people think money is more important than everything else, they seem to have a harder time being happy. And unless they make a great deal of money, they are not on average as happy as others. Perhaps in seeking money they sacrifice other important things too much, such as relationships, spirituality, or following their interests. Or it may be that materialists just can never get enough money to fulfill their dreams—they always want more.

To sum up what makes for a happy life, let’s take the example of Pema. Pema is age 16 and lives in a high mountain village in the Tibet Autonomous Region. Pema lives in a nomadic family which means she and her family move their tent and animals according to the seasons, so the animals can feed on the grasslands. Pema’s family is poor relative to many families. They don’t have much money and they barter with visitors or monks for barley flour when they can, otherwise they eat milk, cheese, yogurt, and meat primarily from their animals. Pema works hard helping with the animals, and enjoys life, despite the hardships. Pema is reasonably satisfied with life. Pema sometimes goes to the cities and can see some families are wealthy. Pema goes to a small local school and enjoys school, but Pema sees that some children in the cities are learning more quickly than she is at age 16. Sometimes they have very little food such as in the middle of winter when there is not enough food for the Yaks whom give the butter and milk and cheese. This is the hardest time for Pema and her family. Pema enjoys her family and friends, her religion of Buddhism, and her connection with nature and the mountains. Her families low income does lower her life satisfaction to some degree especially when they run out of food, but she finds she is able to be happy. Pema has a positive temperament and her enjoyment of social relationships help to some degree to overcome her feelings about the hardships of her life. Pema is aware her family is poor, but most nomad families are poor. Her family has 10 Yaks which is more than her aunt and uncle who only have 3 Yaks, so she feels lucky and her family helps her aunt and uncle whenever they need help.

Tibetan Buddhism, The Middle Way, and Conative Balance

In his first sermon delivered at deer park in Benares in the 11th century, Gotama Buddha revealed the Four Noble Truths and the Middle Way, among other teachings. The middle way is a path of moderation, between the extremes of sensual indulgence and self-mortification. Horne (1917) quotes Gotama Buddha, while speaking to the monks and students gathered as saying: “There are two extremes, oh Bhikkus (monks), which a holy man should avoid–the habitual practice of . . . self-indulgence, which is vulgar and profitless . . . and the habitual practice of self-mortification, which is painful and equally profitless”. The middle way also refers to finding a middle way in negotiation or conflict, such as the proposal by His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama for a compromise with China, allowing Tibet to have independent culture and religion but remain a part of China. China has not accepted the middle way proposal This the Dalai Lama’s offer of compromise is an example of the emphasis of balance in Buddhism. Some pressured the Dalai Lama to insist on total independence for Tibet, while others pressured him to become part of the “one China” policy. The middle way is some of both.

The middle way is often applied to a viewpoint of life that concerning material experiences such as money. Tibetan Buddhists are not forbidden from making money or gaining materialistic items, such as a new iPhone. However, Tibetan Buddhist thought asks the question of “what makes a person truly happy”? Is it materialistic things? Is it money? In his book The Art of Happiness (2020), The Dalai Lama, whom is the exiled leader of Tibet and the spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhism says in Buddhism there is frequent reference to the four factors of fulfillment, or happiness: adequate wealth, worldly satisfaction, spirituality, and enlightenment. Together they embrace the totality of an individual’s quest for happiness. This Buddhist viewpoint is similar to science research on the domains of happiness.

Martin Seligman, one of the founders of positive psychology, has researched happiness domains and has formed a popular assessment instrument called the Perma Profiler, to assess measures of happiness including what Seligman calls flourishing. To flourish is to find fulfillment in our lives, accomplishing meaningful and worthwhile tasks, and connecting with others at a deeper level—in essence, living the “good life” (Seligman, 2011) as Seligman described the PERMA model of flourishing. This model defines psychological wellbeing in terms of 5 domains:

- Positive emotions – P

- Engagement – E

- Relationships – R

- Meaning – M

- Accomplishment – A

Using this model as a framework, the emphasis in life is on increasing our positive emotions, engaging with the world and our work (or hobbies), develop deep and meaningful relationships, find meaning and purpose in our lives, and achieve our goals through cultivating and applying our strengths and talents. To flourish is to find fulfillment in our lives, accomplishing meaningful and worthwhile tasks, and connecting with others at a deeper level—in essence, living the “good life” (Seligman, 2011).

Buddhism has a similar view in the emphasis on domains or factors of fulfillment. However Buddhists put extra emphasis on community living and compassion. In addition to the four factors of fulfillment, The Dalai Lama (2020) states “happiness is found through love, affection, closeness and compassion” and “If you want others to be happy, practice compassion. If you want to be happy, practice compassion.” The Dalai Lama believes not only do humans have the capability of being happy, but also the Dalai Lama believes that each human naturally has a gentle quality within them that can help self and others be happy. Encouraging this gentle quality fosters positive relationships, loving community, and compassionate acts, which Tibetan Buddhists believe has the best chance of making people happy. Buddhism however does not deny the need for material pleasures. It is more an act of balancing various domains of pleasure and behavior and community life. This emphasis on compassion in relationships and community life is found in more recent studies in the scientific happiness research and literature, but perhaps with less emphasis than in Tibetan Buddhism. Sonja Lyubomirsky, a professor of psychology at the University of California, Riverside, has studied happiness for more than 20 years. Her meta summary of happiness research in her 2013 book suggests that acts of kindness and compassion to others are considerably important to our happiness and to our health. Acts of kindness boost positive emotions, thoughts and behavior, in turn improving well-being for the person offering the kindness. Lyubomirsky (2013) adds that there isn’t really a one size fits all approach for acts of kindness. How often a person does acts of kindness, and shows acts of compassion, really depends on the person and context, but overall kindness and compassion are a key factor in happiness according to Lyubomirsky.

The focus on compassion towards others in community a core pillar of happiness in Tibetan Buddhism. Why does Buddhism emphasize this particular aspect of behaviors that connect to happiness?

Interbeing – A Connection Between All People and All Things

Many people are familiar with the golden rule: do unto others as you would have others do unto you! This Christian saying also has great implications when considered from a Buddhist perspective. Based on the same philosophical/cosmological perspective as Yoga, Buddhists believe that there is one universal spirit. Therefore, we are really all the same, indeed the entire universe of living creatures and even inanimate objects in the physical world come from and return to the same, single source of creation. Thus, we could alter the golden rule to something like: as you do unto others you are doing unto yourself! This concept is not simply about being nice to other people for your own good, however. Much more importantly, it is about appreciating the relationships between all things. For example, when you drink a refreshing glass of milk, maybe after eating a few chocolate chip cookies, can you taste the grass and feel the falling rain? After all, the cow could not have grown up to give milk if it hadn’t eaten grass, and the grass would not have grown if there hadn’t been any rain. When you enjoy that milk do you remember to thank the farmer who milked the cow, or the grocer who sold the milk to you? And what about the worms that helped to create and aerate the soil in which the grass grew? Appreciating the concept of interbeing helps us to understand the importance of everyone and everything.

The value of this concept of interbeing is that it can be much more than simply a curious academic topic. The Vietnamese Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh writes very eloquently about interbeing and its potential for promoting healthy relationships, both between people and between societies (Thich Nhat Hanh, 1995):

“Looking deeply” means observing something or someone with so much concentration that the distinction between observer and observed disappears. The result is insight into the true nature of the object. When we look into the heart of a flower, we see clouds, sunshine, minerals, time, the earth, and everything else in the cosmos in it. Without clouds, there could be no rain, and there would be no flower. Without time, the flower could not bloom. In fact, the flower is made entirely of non-flower elements; it has no independent, individual existence. It “inter-is” with everything else in the universe. … When we see the nature of interbeing, barriers between ourselves and others are dissolved, and peace, love, and understanding are possible. Whenever there is understanding, compassion is born. (pg. 10)

The Country of Bhutan: A Case Study of Buddhism and Conative Balance

An interesting case study of Tibetan Buddhism and the concept of conative balance is the country of Bhutan. Bhutan practices a derivative of the Tibetan Buddhism practiced in Tibet, and has many Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, shrines, monks, and nuns. Bhutan focuses as it’s top priority on happiness and balance and follows the principle of conative balance which means desiring wisely. One of the most famous ideas in recent years from the country of Bhutan was the concept of Gross National Happiness (also known by the acronym: GNH). GNH is a philosophy that guides the government of Bhutan. It includes an index which is used to measure the collective happiness and well-being of a population. Gross National Happiness is instituted as the goal of the government of Bhutan in the Constitution of Bhutan, enacted on 18 July 2008. The term “Gross National Happiness” was coined in 1979 during an interview by a British journalist for the Financial Times at Bombay airport when the then king of Bhutan, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, said “Gross National Happiness is more important. Several movies and books have been focused on Bhutan, as it is a country trying to focus on some of the principles of the Buddhist belief of the sanctity of life, the preservation of nature, and living in harmony with the land — rather than focusing on materialistic gain. Bhutan is aiming for conative balance as a country and for individuals. For most of the 20th century Bhutan did not have cars and phones and other technology, in order to preserve their traditions. Their belief is that through actions of conative balance that are imbued in their aspects of their culture, social customs, and dress code, they are more likely to find happiness than following what much of the world has done through modernization. A trailer of the movie Bhutan: Height of Happiness describes these attempts by Bhutan to stay in touch with these principles of happiness.

There is scientific evidence that may lend support to the vision of Bhutan’s leaders and elders to maintain a balance concerning materialistic desire and keep some of their cultural traditions around moderation of desire. Scientists have looked at the traditions of Buddhism and describe the emphasis of Buddhist concerns about desire, as conative balance (Wallace, 1993). Conative balance entails intentions and volitions that are conducive to one’s own and others’ well-being. Conative imbalances, on the other hand, constitute ways in which people’s desires and intentions lead them away from psychological flourishing and into psychological distress (Rinpoche, 2003; Wallace, 1993, pp. 31–43). As discussed in the section above on money and happiness, people who focus on excessive wealth are likely to be less happy or no more happy than those with less money. Bhutan leaders have their challenges ahead, as the youth of Bhutan are requesting access to cable television, a broader fashion choice, and alcohol and drugs.

An essential concept in Buddhism of living a quality life is following the 4 noble truths. The first of the noble truths is “Life is Suffering” but scholars suggest a more accurate translation of this noble truth is that “life brings unsatisfactoriness”. Why Buddhism is True: The Science and Philosophy of Meditation and Enlightenment explains that as we achieve something or gain something, as simple as a food we desire such as a donut, the pleasure of that thing generally fades. Tibetan Buddhism has for many centuries pointed out that in our grasping for permanence of pleasure, we find a certain level of unsatisfactoriness. The Buddhist concept of Samsara can be described as the wheel of life and existence that keeps rotating around and around and involves suffering and pain over and over again. The Buddha taught that if it most helpful for Buddhists to be able to see the world as it really is and this will help break the suffering of the cycle of Samsara. On a practical level, this includes noticing that the grasping for material pleasures brings a certain unsatisfactoriness to it, and that there are deeper principles such as compassion, relationships, and love, that bring more sustainable happiness. Robert Wright summarizes this idea by saying: “ultimately, happiness comes down to choosing between the discomfort of becoming aware of your mental afflictions and the discomfort of being ruled by them.”

Students of psychology have studied human evolution and the nature of drives. Drive states differ from other affective or emotional states in terms of the biological functions they accomplish -that are essential to keep us alive. Whereas all affective states possess valence (i.e., they are positive or negative) and serve to motivate approach or avoidance behaviors (Zajonc, 1998), drive states are unique in that they generate behaviors that result in specific benefits for the body. For example, hunger directs individuals to eat foods that increase blood sugar levels in the body, while thirst causes individuals to drink fluids that increase water levels in the body. Buddhism was aware of the all sorts of drives in humans and the necessity of these drives to keep us alive. This is at its essence, why Buddhism suggested we would make poor decisions regarding our own happiness. As Robert Wright (2017) states: “What kinds of perceptions and thoughts and feelings guide us through life each day?” the answer, at the most basic level, isn’t “The kinds of thoughts and feelings and perceptions that give us an accurate picture of reality.” No, at the most basic level the answer is “The kinds of thoughts and feelings and perceptions that helped our ancestors get genes into the next generation.” Whether those thoughts and feelings and perceptions give us a true view of reality is, strictly speaking, beside the point. As a result, they sometimes don’t. Our brains are designed to, among other things, delude us.” Buddhism is designed to help us see the delusions that are inherently part of our survival system, and facilitate where possible decision-making that will bring well-being. Money and materialism is a key example of this, as humans are deluded that chasing additional wealth, after having an adequate income level, will increase their happiness. Robert Wright (2017) summarizes Buddhist thought this way: “If you want the shortest version of my answer to the question of why Buddhism is true, it’s this: Because we are animals created by natural selection. Natural selection built into our brains the tendencies that early Buddhist thinkers did a pretty amazing job of sizing up, given the meager scientific resources at their disposal. Now, in light of the modern understanding of natural selection and the modern understanding of the human brain that natural selection produced, we can provide a new kind of defense of this sizing up.” Wright (2017) goes on to say: “If you put these three principles of design together, you get a pretty plausible explanation of the human predicament as diagnosed by the Buddha. Yes, as he said, pleasure is fleeting, and, yes, this leaves us recurrently dissatisfied. And the reason is that pleasure is designed by natural selection to evaporate so that the ensuing dissatisfaction will get us to pursue more pleasure. Natural selection doesn’t “want” us to be happy, after all; it just “wants” us to be productive, in its narrow sense of productive. And the way to make us productive is to make the anticipation of pleasure very strong but the pleasure itself not very long-lasting.”

Adaptation to Circumstances

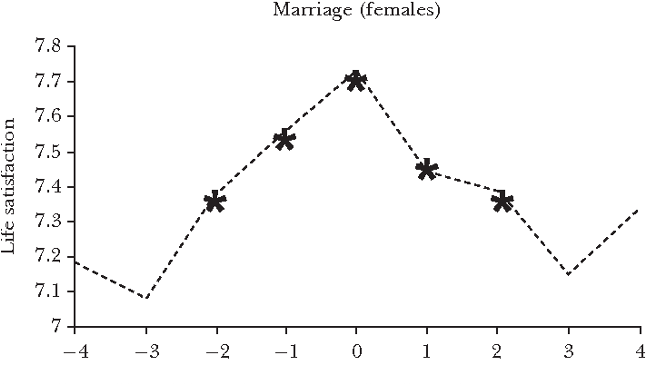

Psychologists have a term for how we adapt to circumstances related to pleasure and pain: the “hedonic treadmill,” or “hedonic adaptation,” a concept that looks at humans as each having a set point or constant level at which they maintain their happiness, regardless of what happens in their lives. We think that getting married will make us permanently happy, or that getting a promotion or making more money will make us more happy. As long as our basic needs are satisfied, we don’t seem to be happier for very long due to these events -because we adapt to the spike in happiness and get back to our normal or “set point” of happiness. Here are a few studies to consider:

Buddhism presents a wide array of meditations designed to remedy specific forms of craving and other obsessive or unrealistic desires and to promote wholesome and realistic aspirations (Shantideva, 1981). Contentment is cultivated by reflecting on the transitory, unsatisfying nature of hedonic pleasures and by identifying and developing the inner causes of genuine well-being. One of the most well-known aspects of Buddhism is meditation. Meditation can take many forms, including being used for insight purposes (called Vipassana meditation), helping a person to think clearly, or meditation can be used to calm the mind and body (called Shamata meditation).

Mindfulness is a mental state achieved by focusing one’s awareness on the present moment, while calmly acknowledging and accepting one’s feelings, thoughts, and bodily sensations. Mindfulness meditation is a form of meditation that can occur throughout every moment of the day. Indeed, it is very important to live fully in every moment, and to look deeply into each experience (Thich Nhat Hanh, 1991, 1995). By being mindful, we can enter into awareness of our body and our emotions. Thich Nhat Hanh, a well-known Buddhist monk and teacher and author, relates a story in which the Buddha was asked when he and his monks practiced. The Buddha replied that they practiced when they sat, when they walked, and when they ate. When the person questioning the Buddha replied that everyone sits, walks, and eats, the Buddha replied that he and his monks knew they were sitting, knew they were walking, and knew they were eating (Thich Nhat Hanh, 1995). Mindfulness can also be applied to acts as simple as breathing. According to Thich Nhat Hanh, conscious breathing is the most basic Buddhist technique for touching peace (Thich Nhat Hanh, 1991, 1995). He suggests silently reciting the following lines while breathing mindfully:

Breathing in, I calm my body.

Breathing out, I smile.

Dwelling in the present moment,

I know this is a wonderful moment!

The Psychological Immune System (we are stronger than we think we are)

Daniel Gilbert (2000), a long-time happiness researcher, identified the idea of miswanting – suggesting humans predict incorrectly in many situations what will make them happy. This includes how we predict what will make us happy in our future and how much we will like or dislike something. Wright (2017) suggests miswanting is strongly rooted in our minds desire to keep us alive, so throughout evolution the human mind has learned to favor things such material possessions, status, and aggression, which in some situations would help us stay alive. However our mind can trick us to overusing these tendencies and the goal identified in both Buddhism and scientific research is to gain awareness of the mind’s tendency to miswant and mispredict.

Related to the idea of miswanting or mispredicting, Gilbert (1998) coined the term “immune neglect” to discuss our lack of awareness of something called our psychological immune system. The psychological immune system is a mental mechanism where our brain become helpful in creating solutions to our problems when we are under pressure. Based partly on how the brain processes cognitive dissonance and can use bias to help a person feel better, the psychological immune system will only come in to effect when it really has to. Gilbert suggests we essentially “synthesize happiness” when we don’t get what we wanted, or we don’t get what we thought we wanted. If we do get what we wanted, we feel something Gilbert calls natural happiness. But often in life we don’t get what we wanted or planned. Here the brain has the ability to synthesize happiness, which is the brain’s ability to resolve dissonance and make the new road we are on and the new choices we have in life as valuable as the old road and old choices that were taken away from us. An example of the psychological immune system can be seen in the following student video. Selam was set on getting into medical school and was doing quite well in her pre-med courses and working as a medical scribe, but she would learn that based on her early grades it would be quite challenging to get into medical school. Within a few months, Selam’s psychological immune system kicks in and she begins to focus on the negative parts of a career in medicine, and how some opportunities in organizational psychology might be a better fit. Gilbert (2007) suggests synthesized happiness is every bit as good as natural happiness, and that is the magic of it all – that the mind really does highlight and help us understand the benefits of the new path we are on.

The SELF and Wanting to Be Happy?

At the center of the ideas of miswanting and mispredicting how we will react to positive or negative circumstances, is the idea of whether humans have a brain that runs things accurately for their own happiness, and whether in the center of that brain is a “self”. You can think of this as whether the internet has a self? Who runs the internet? It is a lot of knowledge, but is their a center of the internet? This chapter won’t be able to answer the question of whether humans have a central self, but it is worth thinking about in terms of happiness. Recent psychological scientists question whether their is a central human self. As mentioned above in the book by Robert Wright (2017) on why Buddhism is true, Wright compares scientific advances with Buddhist thought. His argument is that science has yet to discover any particular “center” of the human mind where the self would be located. This is similar to the idea Buddhism has put forward for centuries. One view of the human mind currently popular among evolutionary psychologist is called the modularity of the mind (Fodor, 1983). Evolutionary psychologists propose that the mind is made up of genetically influenced and domain-specific mental algorithms or computational modules, designed to solve specific evolutionary problems of the past. An alternative view is the domain-general processing view, in which mental activity is distributed across the brain and cannot be decomposed, even abstractly, into independent units (Uttal, 2003). What is interesting across the models of the mind that scientists are using, is thus far nobody has identified the center of the mind. Wright (2017) suggests: “In other words, if you were to build into the brain a component in charge of public relations, it would look something like the conscious self.” Wright and other scientists are suggesting that as there is no center of the mind, no inherent “self”, the most convincing module for the center of our mind may be the part of our mind that advocates for us as humans and makes us believe we are in charge. That makes us believe what we are doing is correct, or right, and make decisions in sensible ways. This view of the mind having a module that convinces us we have a central self, has a lot to do with bias, anger, and hatred. If we are so sure we are a “self” and that self is absolutely correct about our thoughts and feelings and reactions, we will act with more absolutism and potentially hurt others and act aggressively with a sense of “self”-righteousness. The reason for this is we are sure that our “self” or the center of who we are, is giving us accurate non-biased information. The same is true of cravings and needs– our self tells us we “must” eat a donut or drink a beer or we won’t feel well.

Buddhism has questioned this idea of the self. In the following video, listen to Lama Lakshey Zangpo Rinpoche, a respected Tibetan Buddhist teacher, talk briefly about the Tibetan Buddhist idea of the self.

Perhaps the take home idea of this discussion of whether we have a self or not is this: A fundamental insight of Buddhism is the recognition of the fluctuating, impermanent nature of all phenomena that arise in dependence on preceding causes and contributing conditions. Mistakenly grasping objective things and events as true sources happiness produces a wide range of psychological problems, at the root of which is an overemphasis on oneself, as an immutable, unitary, independent ego (Ricard, 2006). When you our Self is unchangeable in all things, it sets us up a belief system that.

The Comparing Mind

The following video illustrates one of the central concepts related to happiness – comparison. As discussed above with the example of 16-year old Pema, she is happy with her life even though she knows others have some things easier. The following video illustrates this concept, as a woman named Norzom whom grew up living a very challenging nomadic life in the high mountains of Tibet, discusses her view on happiness.

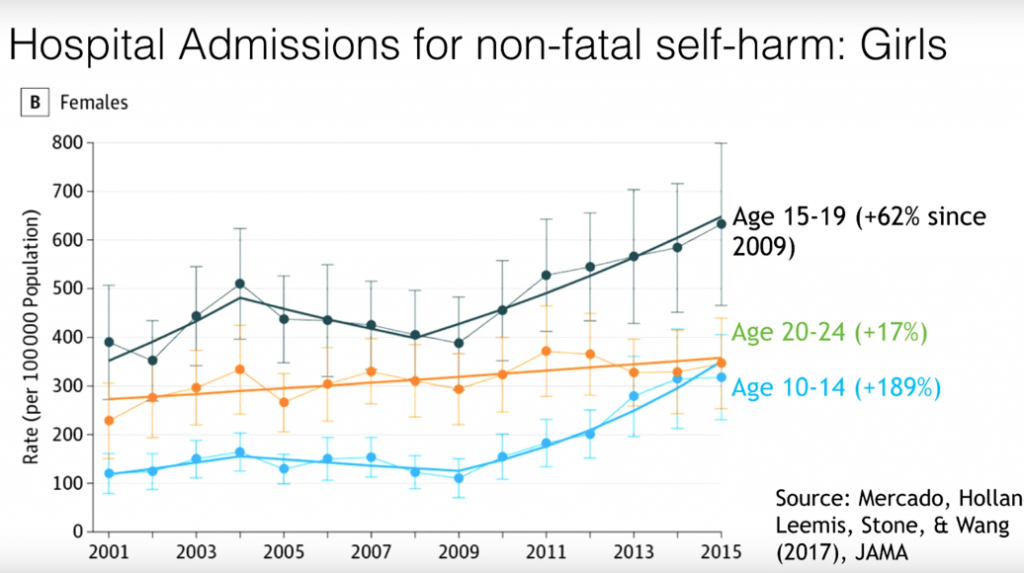

With the invention of social media, social comparison has become a critically important topic. One of the more alarming studies related to social media effects was published in the Journal of American Medical Association in 2017. The authors suggest the increase for non-fatal self-harm among age groups for girls increases significantly, showing spikes that correlate to increased phone usage and app usage such as Facebook. Particularly for girls that were ages 10-14 at the time of final measurement in 2015, the increase in self-harm was extreme, suggesting the younger a person is the more vulnerable they will be to social comparison, and that gender plays an important role in social comparison.

Tibetan Buddhism has long focused on avoiding comparisons of self to others as a key to well-being. Buddhism believes there will always be others with more or less, and that our state of mind that can contemplate this fact that there is always more or less, and that a person may be anywhere in this cycle of having or not having, is the key to maintaining our happiness. Buddhism teaching is often helping students of Buddhism to train their mind in the relativity of what people own, or what abilities and achievements others have, but to not let this be the focus of one’s happiness. The Dalai Lama (2020) says it this way:

“If we utilize our favorable circumstances, such as our good health or wealth, in positive ways, in helping others, they can be contributory factors in achieving a happier life. And of course we enjoy these things—our material facilities, success, and so on. But without the right mental attitude, without attention to the mental factor, these things have very little impact on our long-term feelings of happiness. For example, if you harbor hateful thoughts or intense anger somewhere deep down within yourself, then it ruins your health; thus it destroys one of the factors. Also, if you are mentally unhappy or frustrated, then physical comfort is not of much help. On the other hand, if you can maintain a calm, peaceful state of mind, then you can be a very happy person even if you have poor health. Or, even if you have wonderful possessions, when you are in an intense moment of anger or hatred, you feel like throwing them, breaking them. At that moment your possessions mean nothing.

Outcomes of High Subjective Well-Being

Is the state of happiness truly a good thing? Is happiness simply a feel-good state that leaves us unmotivated and ignorant of the world’s problems? Should people strive to be happy, or are they better off to be grumpy but “realistic”? Some have argued that happiness is actually a bad thing, leaving us superficial and uncaring. Most of the evidence so far suggests that happy people are healthier, more sociable, more productive, and better citizens (Diener & Tay, 2012; Lyubomirsky, King, & Diener, 2005). Research shows that the happiest individuals are usually very sociable. The table below summarizes some of the major findings.

Although it is beneficial generally to be happy, this does not mean that people should be constantly euphoric. In fact, it is appropriate and helpful sometimes to be sad or to worry. At times a bit of worry mixed with positive feelings makes people more creative. Most successful people in the workplace seem to be those who are mostly positive but sometimes a bit negative. Thus, people need not be a superstar in happiness to be a superstar in life. What is not helpful is to be chronically unhappy. The important question is whether people are satisfied with how happy they are. If you feel mostly positive and satisfied, and yet occasionally worry and feel stressed, this is probably fine as long as you feel comfortable with this level of happiness. If you are a person who is chronically unhappy much of the time, changes are needed, and perhaps professional intervention would help as well.

The Dalai Lama and Tibetan Buddhist teachers view happiness as a journey, not a destination. Rather than an emphasis on large events to make us happy, the focus is on a way of living. The Dalai Lama (2020) says: “So let us reflect on what is truly of value in life, what gives meaning to our lives, and set our priorities on the basis of that. The purpose of our life needs to be positive. We weren’t born with the purpose of causing trouble, harming others. For our life to be of value, I think we must develop basic good human qualities-warmth, kindness, compassion. Then our life becomes meaningful and more peaceful-happier.” This quote sends the message that certain qualities of kindness, compassion, are more important than being a happiness superstar. And that these happiness habits create positive community and are good for all of us.

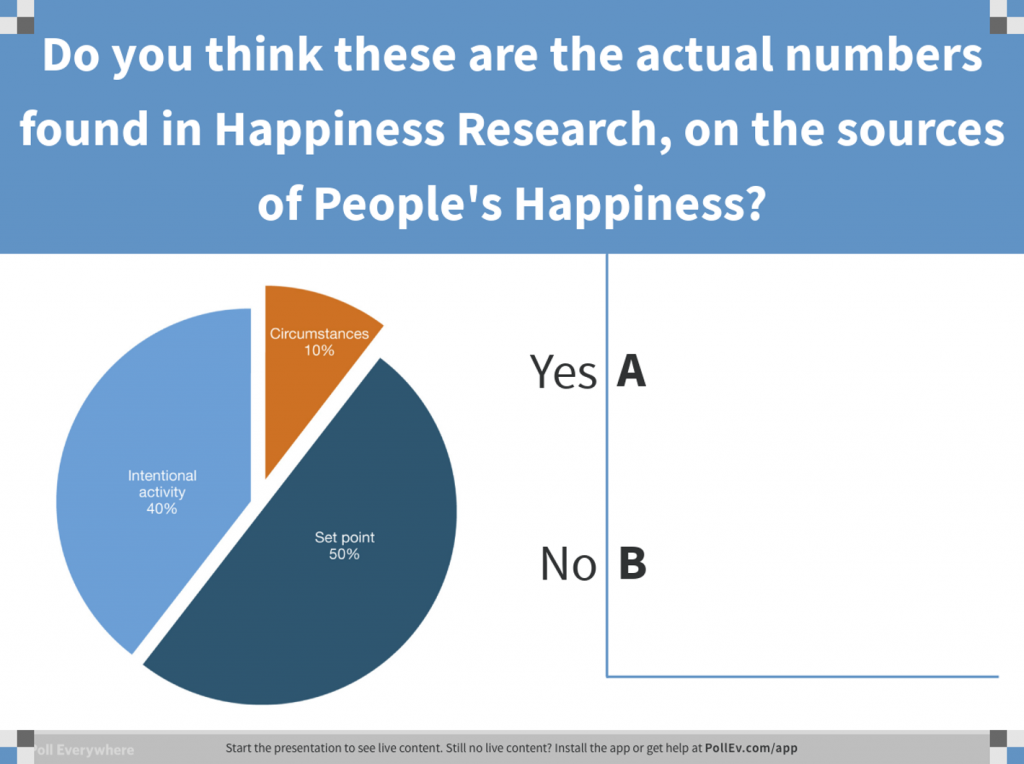

Don’t Forget Genetics and Set Point

Sometimes when people read about the outcomes of happiness, and that being happy can cause a person to have better life outcomes, they become frustrated or use this information as a weapon against themself, saying something like: “if I were only more happy, I’d be happier”. This may be motivating to some persons but is often experienced as a self-criticism. Sonya Lyubomirsky’s (2013) work on the set point of happiness, including delving deeply in to the research on identical twins raised separately and together, is important to emphasize, because the role of biology and early experiences needs to be considered as a human happiness diversity issue. Not everyone, perhaps not most of us, will be a bouncy happy person, and that has something clear to do with nature. On the other hand, 40% of our life is under our control to make decisions to improve our happiness. The video of Rafael below is a good example of set point. Rafael discusses challenges with a medical diagnosis as a young adult. Yet he states that he has always had an optimistic approach and that this helped him move through the challenges of the medical diagnosis.

Measuring Happiness

Dan Gilbert (2007) suggests it is very hard to predict our future happiness, because whatever we think will make us happier in the future is very possibly untrue because we are likely to base our feeling on what is going on in the present. This is related to the previous discussion of miswanting and mispredicting. Specifically – we use our “pre-feelings” or feelings now about an experience to predict how we will feel about it in the future. Marriage is a good example. How we feel about someone in the present, may or may not last. Another example is that humans often predict based on their youthful energy that they will have this same energy in the second half of life. But as we age we get more tired, and at times wish we’d made choices that would make our life easier and require less energy, such as saving money for the future so we had to work less as we age. All this said, much of happiness research does require self-report measures, especially of our current happiness and SWB levels, and these self-report measures have found relatively good levels of of validity — meaning they do actually measure something about how happy a person currently is.

The self-report scales have proved to be relatively valid (Diener, Inglehart, & Tay, 2012), although people can lie, or fool themselves, or be influenced by their current moods or situational factors. Because the scales are imperfect, well-being scientists also sometimes use biological measures of happiness (e.g., the strength of a person’s immune system, or measuring various brain areas that are associated with greater happiness). Scientists also use reports by family, coworkers, and friends—these people reporting how happy they believe the target person is. Other measures are used as well to help overcome some of the shortcomings of the self-report scales, but most of the field is based on people telling us how happy they are using numbered scales.

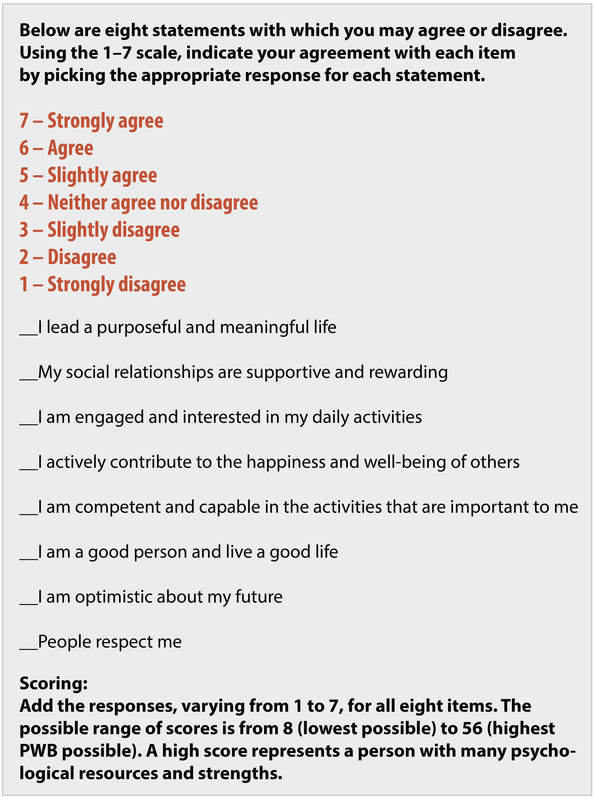

There are scales to measure life satisfaction (Pavot & Diener, 2008), positive and negative feelings, and whether a person is psychologically flourishing (Diener et al., 2009). Flourishing has to do with whether a person feels meaning in life, has close relationships, and feels a sense of mastery over important life activities. You can take the well-being scales created in the Diener laboratory, and let others take them too, because they are free and open for use.

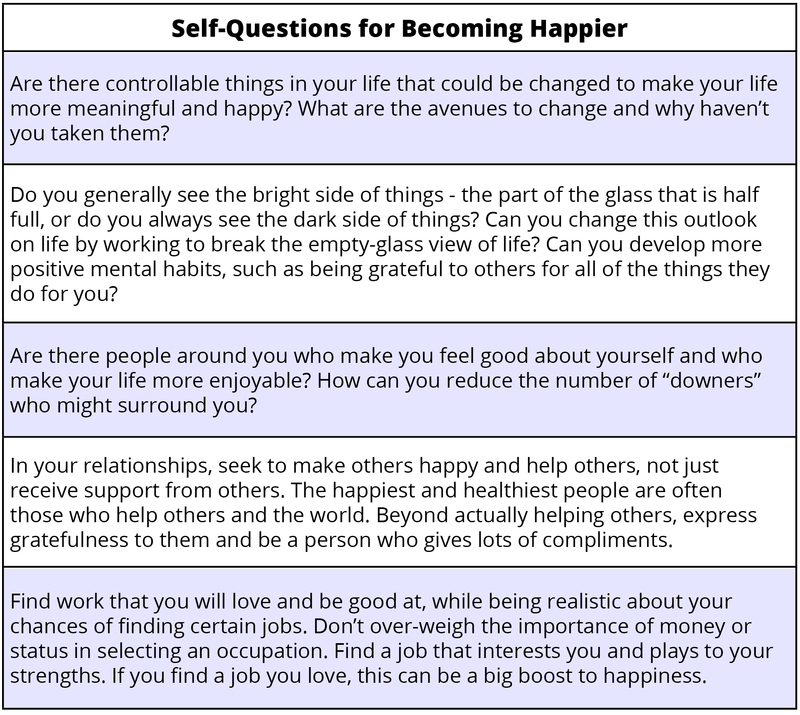

Some Ways to Be Happier

Most people are fairly happy, but many of them also wish they could be a bit more satisfied and enjoy life more. Prescriptions about how to achieve more happiness are often oversimplified because happiness has different components and prescriptions need to be aimed at where each individual needs improvement—one size does not fit all. A person might be strong in one area and deficient in other areas. People with prolonged serious unhappiness might need help from a professional. Thus, recommendations for how to achieve happiness are often appropriate for one person but not for others. With this in mind, I list in Table 4 below some general recommendations for you to be happier (see also Lyubomirsky, 2013):

-

The Dalai Lama’s Suggestions for Happiness

As we’ve seen in this chapter, Tibetan Buddhism teachings as typified by the teachings of the Dalai Lama and others, parallels research from scientific exploration. Everything in the Table 4 could also be shared in teachings of Tibetan Buddhism. As stated above, Tibetan Buddhism has extra weight it places on compassion and kindness to self and within community living. Tibetan Buddhism also suggests that we become actively engaged in training the mind- or learning about the psychology of happiness. The Dalai Lama (2020) puts it this way:

I say ‘training the mind,’ in this context I’m not referring to ‘mind’ merely as one’s cognitive ability or intellect. Rather, I’m using the term in the sense of the Tibetan word Sem, which has a much broader meaning, closer to ‘psyche’ or ‘spirit’, it includes intellect and feeling, heart and mind.

Congratulations to students who have completed this chapter, as it is a step toward beginning to understand your own psyche and your own habits of happiness.

-

Outsides Resources

- Web: Sonja Lyubomirsky’s website on happiness

- http://sonjalyubomirsky.com/

- Web: Ed Diener’s website

- http://internal.psychology.illinois.edu/~ediener/

- Web: University of Pennsylvania Positive Psychology Center website

- http://www.ppc.sas.upenn.edu/

- Web: World Database on Happiness

- http://www1.eur.nl/fsw/happiness/

Discussion Questions

- Which do you think is more important, the “top-down” personality influences on happiness or the “bottom-up” situational circumstances that influence it? In other words, discuss whether internal sources such as personality and outlook or external factors such situations, circumstances, and events are more important to happiness. Can you make an argument that both are very important?

- Do you know people who are happy in one way but not in others? People who are high in life satisfaction, for example, but low in enjoying life or high in negative feelings? What should they do to increase their happiness across all three types of subjective well-being?

- Certain sources of happiness have been emphasized in this book, but there are others. Can you think of other important sources of happiness and unhappiness? Do you think religion, for example, is a positive source of happiness for most people? What about age or ethnicity? What about health and physical handicaps? If you were a researcher, what question might you tackle on the influences on happiness?

- Are you satisfied with your level of happiness? If not, are there things you might do to change it? Would you function better if you were happier?

- How much happiness is helpful to make a society thrive? Do people need some worry and sadness in life to help us avoid bad things? When is satisfaction a good thing, and when is some dissatisfaction a good thing?

- How do you think money can help happiness? Interfere with happiness? What level of income will you need to be satisfied?

Vocabulary

- Adaptation

- The fact that after people first react to good or bad events, sometimes in a strong way, their feelings and reactions tend to dampen down over time and they return toward their original level of subjective well-being.

- “Bottom-up” or external causes of happiness

- Situational factors outside the person that influence his or her subjective well-being, such as good and bad events and circumstances such as health and wealth.

- Conative balance: desiring wisely, including desires that benefit self and other beings.

- Happiness

- The popular word for subjective well-being. Scientists sometimes avoid using this term because it can refer to different things, such as feeling good, being satisfied, or even the causes of high subjective well-being.

Hedonic Adaptation: a concept that looks at humans as each having a set point or constant level at which they maintain their happiness, regardless of what happens in their lives. Also, a general term for how people adapt to positive and negative experiences.

Interbeing: Buddhists believe that there is one universal spirit. Therefore, we are really all the same, indeed the entire universe of living creatures and even inanimate objects in the physical world come from and return to the same, single source of creation.

Middle Way: The middle way is a path of moderation, between the extremes of sensual indulgence and self-mortification.

Mindfulness: is a mental state achieved by focusing one’s awareness on the present moment, while calmly acknowledging and accepting one’s feelings, thoughts, and bodily sensations.

Miswanting or Mispredicting: humans predict incorrectly in many situations what will make them happy, or that humans want the incorrect things.

- Negative feelings

- Undesirable and unpleasant feelings that people tend to avoid if they can. Moods and emotions such as depression, anger, and worry are examples.

- Positive feelings

- Desirable and pleasant feelings. Moods and emotions such as enjoyment and love are examples.

- Psychological immune system is a mental mechanism where our brain help us find helpful solutions to our problems when we are under pressure. One way it can do this is to synthesize happiness, making us feel that if we don’t get what we want, we can still be equally happy with our new life.

- Subjective well-being

- The name that scientists give to happiness—thinking and feeling that our lives are going very well.

Tibetan Buddhism: a form of philosophy and type of Buddhism practiced by the people of Tibet, and elsewhere in the world. Tibetan Buddhism is based in the teachings of the Buddha as introduced to the country of Tibet between the 7th and 9th centuries.

- “Top-down” or internal causes of happiness

- The person’s outlook and habitual response tendencies that influence their happiness—for example, their temperament or optimistic outlook on life.

References

- Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542–575.

- Diener, E., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2008). Happiness: Unlocking the mysteries of psychological wealth. Malden, MA: Wiley/Blackwell.

- Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Beyond money: Toward an economy of well-being. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 5, 1–31.

- Diener, E., & Tay, L. (2012). The remarkable benefits of happiness for successful and healthy living. Report of the Well-Being Working Group, Royal Government of Bhutan. Report to the United Nations General Assembly: Well-Being and Happiness: A New Development Paradigm.

- Diener, E., Inglehart, R., & Tay, L. (2012). Theory and validity of life satisfaction scales. Social Indicators Research, in press.

- Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276–302.

- Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2009). New measures of well-being: Flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 39, 247–266.

- Fodor, Jerry A. (1983). Modularity of Mind: An Essay on Faculty Psychology. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Gilbert & Wilson (2000).”Miswanting: Some problems in the forecasting of future affective states.” In Thinking and feeling: The role of affect in social cognition. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. Pages 178-197.

- Gilbert, D. (2007). Stumbling on Happiness. Vintage Publishers.

- Horne, J. (1917) The Sacred Books and Early Literature of the East, Volume 10, London: 1917.

- Hayes, S. (2005). Get Out of Your Mind and Into Your Life: The New Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (A New Harbinger Self-Help Workbook)

- Lama, His Holiness Dalai,, Cutler, H. (2020) The Art of Happiness: A Handbook for Living.

- Lucas et al. (2003). Reexamining Adaptation and the Set Point Model of Happiness: Reactions to Changes in Marital Status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(3), 527-539.

- Lyubomirsky, S. (2013). The myths of happiness: What should make you happy, but doesn’t, what shouldn’t make you happy, but does. New York, NY: Penguin.

- Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131, 803–855.

- Lyubomirsky, S., Tucker, KL. (2001) Responses to hedonically conflicting social comparisons: Comparing happy and unhappy people. European Journal of Social and Personality Psychology.

- Medvec, VH. (1995). When less is more: counterfactual thinking and satisfaction among Olympic medalists. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995 Oct;69(4):603-10. doi: 10.1037

- Myers, D. G. (1992). The pursuit of happiness: Discovering pathways to fulfillment, well-being, and enduring personal joy. New York, NY: Avon.

- Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2008). The Satisfaction with life scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3, 137–152.

- Rinpoche, C. T. (2003). Parting from the four attachments. Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion.

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-being. New York City, NY: Atria Books.

- Tworkov, H. Interbeing with Thich Nhat Hanh: An Interview. Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Summer 1995.

- Shantideva. (1997). A guide to the bodhisattva way of life (V. A. Wallace & B. A. Wallace, Trans.). Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion.

- Uttal, William R. (2003). The New Phrenology: The Limits of Localizing Cognitive Processes in the Brain. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Wallace, B. A. (2003). Introduction: Buddhism and science—Breaking down the barriers. In B. A. Wallace (Ed.), Buddhism and science: Breaking new ground (pp. 1–30). New York: Columbia University Press.

- Why Buddhism is True: The Science and Philosophy of Meditation and Enlightenment. Simon and Schuster.

Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike

This is an edited and adapted chapter from the NOBA psychology website. The original authors bear no responsibility for its content. The original content can be accessed at: