4 Sigmund Freud, Karen Horney, Nancy Chodorow: Viewpoints on Psychodynamic Theory

This is an edited and adapted chapter from Bornstein, R. (2019) in the NOBA series on psychology. For full attribution see end of chapter.

Originating in the work of Sigmund Freud, the psychodynamic perspective emphasizes unconscious psychological processes (for example, wishes and fears of which we’re not fully aware), and contends that childhood experiences are crucial in shaping adult personality. The psychodynamic perspective has evolved considerably since Freud’s time, and now includes innovative new approaches such as object relations theory and neuropsychoanalysis. Some psychodynamic concepts have held up well to empirical scrutiny while others have not, and aspects of the theory remain controversial, but the psychodynamic perspective continues to influence many different areas of contemporary psychology.

Learning Objectives

- Describe the basic ideas of Sigmund Freud

- Describe the basic ideas of Karen Horney

- Describe some ideas that Nancy Chodorow added to Psychodynamic Theories

Introduction

Have you ever done something that didn’t make sense? Perhaps you waited until the last minute to begin studying for an exam, even though you knew that delaying so long would ensure that you got a poor grade. Or maybe you spotted a person you liked across the room—someone about whom you had romantic feelings—but instead of approaching that person you headed the other way (and felt ashamed about it afterward). If you’ve ever done something that didn’t seem to make sense—and who among us hasn’t—the psychodynamic perspective on personality might be useful for you. It can help you understand why you chose not to study for that test, or why you ran the other way when the person of your dreams entered the room.

Psychodynamic theory (sometimes called psychoanalytic theory) explains personality in terms of unconscious psychological processes (for example, wishes and fears of which we’re not fully aware), and contends that childhood experiences are crucial in shaping adult personality. Psychodynamic theory is most closely associated with the work of Sigmund Freud, and with psychoanalysis, a type of psychotherapy that attempts to explore the patient’s unconscious thoughts and emotions so that the person is better able to understand themself.

Freud’s work has been extremely influential, its impact extending far beyond psychology (several years ago Time magazine selected Freud as one of the most important thinkers of the 20th century). Freud’s work has been not only influential, but quite controversial as well. As you might imagine, when Freud suggested in 1900 that much of our behavior is determined by psychological forces of which we’re largely unaware—that we literally don’t know what’s going on in our own minds—people were (to put it mildly) displeased (Freud, 1900/1953a). When he suggested in 1905 that we humans have strong sexual feelings from a very early age, and that some of these sexual feelings are directed toward our parents, people were more than displeased—they were outraged (Freud, 1905/1953b). Few theories in psychology have evoked such strong reactions from other professionals and members of the public.

Controversy notwithstanding, no competent psychologist, or student of psychology, can ignore psychodynamic theory. It is simply too important for psychological science and practice, and continues to play an important role in a wide variety of disciplines within and outside psychology (for example, developmental psychology, social psychology, sociology, and neuroscience; see Bornstein, 2005, 2006; Solms & Turnbull, 2011). This module reviews the psychodynamic perspective on personality. We begin with a brief discussion of the core assumptions of psychodynamic theory, followed by an overview of the evolution of the theory from Freud’s time to today. We then discuss the place of psychodynamic theory within contemporary psychology, and look toward the future as well.

Core Assumptions of the Psychodynamic Perspective

The core assumptions of psychodynamic theory are surprisingly simple. Moreover, these assumptions are unique to the psychodynamic framework: No other theories of personality accept these three ideas in their purest form.

Assumption 1: Primacy of the Unconscious

Psychodynamic theorists contend that the majority of psychological processes take place outside conscious awareness. In psychoanalytic terms, the activities of the mind (or psyche) are presumed to be largely unconscious. Research confirms this basic premise of psychoanalysis: Many of our mental activities—memories, motives, feelings, and the like—are largely inaccessible to consciousness (Bargh & Morsella, 2008; Bornstein, 2010; Wilson, 2009).

Assumption 2: Critical Importance of Early Experiences

Psychodynamic theory is not alone in positing that early childhood events play a role in shaping personality, but the theory is unique in the degree to which it emphasizes these events as determinants of personality development and dynamics. According to the psychodynamic model, early experiences—including those occurring during the first weeks or months of life—set in motion personality processes that affect us years, even decades, later (Blatt & Levy, 2003; McWilliams, 2009). This is especially true of experiences that are outside the normal range (for example, losing a parent or sibling at a very early age).

Assumption 3: Psychic Causality

The third core assumption of psychodynamic theory is that nothing in mental life happens by chance—that there is no such thing as a random thought, feeling, motive, or behavior. This has come to be known as the principle of psychic causality, and though few psychologists accept the principle of psychic causality precisely as psychoanalysts conceive it, most theorists and researchers agree that thoughts, motives, emotional responses, and expressed behaviors do not arise randomly, but always stem from some combination of identifiable biological and psychological processes (Elliott, 2002; Robinson & Gordon, 2011).

The Evolution of Psychodynamic Theory

Given Freud’s background in neurology, it is not surprising that the first incarnation of psychoanalytic theory was primarily biological: Freud set out to explain psychological phenomena in terms that could be linked to neurological functioning as it was understood in his day. Because Freud’s work in this area evolved over more than 50 years (he began in 1885, and continued until he died in 1939), there were numerous revisions along the way. Thus, it is most accurate to think of psychodynamic theory as a set of interrelated models that complement and build upon each other. Three are particularly important: the topographic model, the psychosexual stage model, and the structural model.

The Topographic Model

In his 1900 book, The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud introduced his topographic model of the mind, which contended that the mind could be divided into three regions: conscious, preconscious, and unconscious. The conscious part of the mind holds information that you’re focusing on at this moment—what you’re thinking and feeling right now. The preconscious contains material that is capable of becoming conscious but is not conscious at the moment because your attention is not being directed toward it. You can move material from the preconscious into consciousness simply by focusing your attention on it. Consider, for example, what you had for dinner last night. A moment ago that information was preconscious; now it’s conscious, because you “pulled it up” into consciousness. (Not to worry, in a few moments it will be preconscious again, and you can move on to more important things.)

The unconscious—the most controversial part of the topographic model—contains anxiety-producing material (for example, sexual impulses, aggressive urges) that are deliberately repressed (held outside of conscious awareness as a form of self-protection because they make you uncomfortable). The terms conscious, preconscious, and unconscious continue to be used today in psychology, and research has provided considerable support for Freud’s thinking regarding conscious and preconscious processing (Erdelyi, 1985, 2004). The existence of the unconscious remains controversial, with some researchers arguing that evidence for it is compelling and others contending that “unconscious” processing can be accounted for without positing the existence of a Freudian repository of repressed wishes and troubling urges and impulses (Eagle, 2011; Luborsky & Barrett, 2006).

The Psychosexual Stage Model

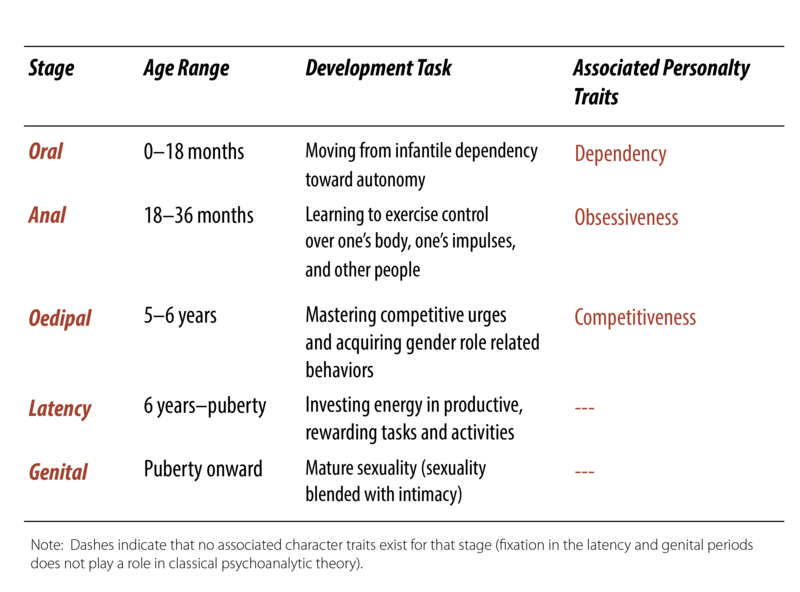

Freud remained devoted to the topographic model, but by 1905 he had outlined the key elements of his psychosexual stage model, which argued that early in life we progress through a sequence of developmental stages, each with its own unique challenge and its own mode of sexual gratification. Freud’s psychosexual stages—oral, anal, Oedipal, latency, and genital—are well-known even to non-analytic psychologists. Frustration or overgratification during a particular stage was hypothesized to result in “fixation” at that stage, and to the development of an oral, anal, or Oedipal personality style (Bornstein, 2005, 2006).

Table 1 illustrates the basic organization of Freud’s (1905/1953b) psychosexual stage model, and the three personality styles that result. Note that—consistent with the developmental challenges that the child confronts during each stage—oral fixation is hypothesized to result in a dependent personality, whereas anal fixation results in a lifelong preoccupation with control. Oedipal fixation leads to an aggressive, competitive personality orientation.

In contemporary psychological circles, he psychosexual stage model is not commonly used as a basis for understanding mental illness, although some theories still consider the implications of developmental fixations, and some psychodynamic schools still utilize thinking surrounding the psychosexual stages. An example of current interest in psychosexual stages is examining the origin of sexual compulsions. Some sex therapists and researchers examine with their clients the information contained in their sexual arousal templates. (Carnes, 2011) A sexual arousal template consists of the total constellation of thoughts, images, behaviors, sounds, smells, sights, fantasies, and objects that arouse us sexually (Carnes, 2011). Some of these sexual arousal templates may be based in psychosexual development experiences. Psychoanalytic literature and sex therapy literature examine cases where a client, for example, has a fixation as an adult for example on breasts, and whether this relates to a psychosexual stage fixation in a stage such as the oral stage. Modern sex therapy is more often cognitive-behavioral in it’s emphasis, however psychsexual developmental stages and fixation models still hold the interest of not only of psychologists, but the imaginations of literary writers and movie makers.

The Structural Model

Ultimately, Freud recognized that the topographic model was helpful in understanding how people process and store information, but not all that useful in explaining other important psychological phenomena (for example, why certain people develop psychological disorders and others do not). To extend his theory, Freud developed a complementary framework to account for normal and abnormal personality development—the structural model—which posits the existence of three interacting mental structures called the id, ego, and superego. The id is the seat of drives and instincts, whereas the ego represents the logical, reality-oriented part of the mind, and the superego is basically your conscience—the moral guidelines, rules, and prohibitions that guide your behavior. (You acquire these through your family and through the culture in which you were raised.)

According to the structural model, our personality reflects the interplay of these three psychic structures, which differ across individuals in relative power and influence. When the id predominates and instincts rule, the result is an impulsive personality style. When the superego is strongest, moral prohibitions reign supreme, and a restrained, overcontrolled personality ensues. When the ego is dominant, a more balanced set of personality traits develop (Eagle, 2011; McWilliams, 2009).

The Ego and Its Defenses

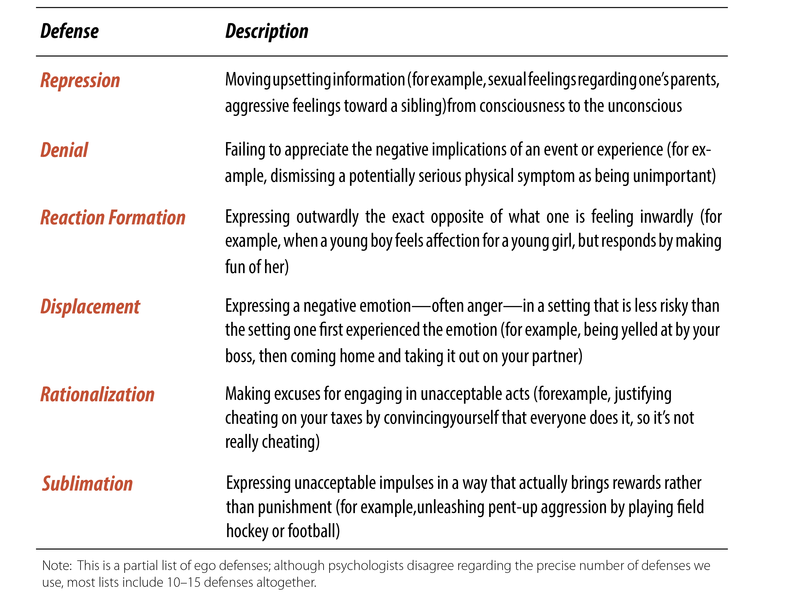

In addition to being the logical, rational, reality-oriented part of the mind, the ego serves another important function: It helps us manage anxiety through the use of ego defenses. Ego defenses are basically mental strategies that we use automatically and unconsciously when we feel threatened (Cramer, 2000, 2006). They help us navigate upsetting events, but there’s a cost as well: All ego defenses involve some distortion of reality. For example, repression (the most basic ego defense, according to Freud) involves removing from consciousness upsetting thoughts and feelings, and moving those thoughts and feelings to the unconscious. When you read about a person who “blocked out” upsetting memories of child abuse, that’s an example of repression.

Another ego defense is denial. In denial (unlike repression), we are aware that a particular event occurred, but we don’t allow ourselves to see the implications of that event. When you hear a person with a substance abuse problem say “I’m fine—even though people complain about my drinking I never miss a day of work,” that person is using denial. Table 2 lists some common ego defenses in psychodynamic theory, along with a definition and example of each.

Table 1: The Psychosexual Stage Model

Karen Horney: A Contrast to Freud

Karen Horney stands alone as the only woman traditionally included in textbooks about the history of personality. She did not, however, focus her entire career on the psychology of women. Horney came to believe that culture was more important than gender in determining differences between men and women. Karen Horney’s career intersected many areas of psychology, relevant both to the past and to the future. One of the first women trained in psychoanalysis, she was the first to challenge Freud’s views on women. She did not, however, attempt to reject his influence, but rather, felt that she honored him by building upon his achievements. The most significant change that she felt needed to be made was a shift away from the biological/medical model of Freud to one in which cultural factors were at least as important. Indeed, she challenged Freud’s fundamental belief that anxiety follows biological impulses, and instead suggested that our behaviors adapt themselves to a fundamental anxiety associated with the simple desire for survival and to cultural determinants of abnormal, anxiety-provoking situations.

Horney was also significant in the development of psychodynamic theory and psychoanalysis in America. She helped to establish psychoanalytic societies and training institutes in Chicago and New York. She was a friend and colleague to many influential psychoanalysts, including Harry Stack Sullivan and Erich Fromm. She encouraged cross-cultural research and practice through her own example, not only citing the work of anthropologists and sociologists, but also through her personal interest and support for the study of Zen Buddhism.

Although Horney herself abandoned the study of feminine psychology, suggesting instead that it represented the cultural effect of women being an oppressed minority group, her subsequent emphasis on the importance of relationships and interpersonal psychodynamic processes laid the foundation for later theories on the psychology of women (such as the relational-cultural model). Thus, her influence is still being felt quite strongly today.

Horney’s Shifting Perspectives on Psychodynamic Theory

Feminine Psychology

Horney was neither the first, nor the only, significant woman in the early days of psychodynamic theory and psychoanalysis. However, women such as Helene Deutsch, Marie Bonaparte, Anna Freud, and Melanie Klein remained faithful to Freud’s basic theories. In contrast, Horney directly challenged Freud’s theories, and offered her own alternatives. In doing so, she offered a very different perspective on the psychology of women and personality development in girls and women. Her papers have been collected and published in Feminine Psychology by her friend and colleague Harold Kelman (1967), and an excellent overview of their content can be found in the biography written by Rubins (1978).

Of most importance, Horney thought, was the male bias inherent in society and culture. The very name phallic stage that Freud used for one of the psychosexual stages, implies that only someone with a phallus (penis) can achieve sexual satisfaction and healthy personality development. Girls are repeatedly made to feel inferior to boys, feminine values are considered inferior to masculine values, even motherhood is considered a burden for women to bear (according to the Bible, the pain of childbirth is a curse from God!). In addition, male-dominated societies do not provide women with adequate outlets for their creative drives. As a result, many women develop a masculinity complex, involving feelings of revenge against men and the rejection of their own feminine traits. Thus, it may be true that women are more likely to suffer from anxiety and other psychological disorders, but this is not due to an inherent inferiority as proposed by Freud. Rather, women find it difficult in a patriarchal society to fulfill their personal development in accordance with their individual personality (unless they naturally happen to fit into society’s expectations).

Perhaps the most curious aspect of these early studies was the fact that Horney turned the tables on Freud and his concept of penis envy. The female’s biological role in childbirth is vastly superior (if that is a proper term) to that of the male. Horney noted that many boys express an intense envy of pregnancy and motherhood. If this so-called womb envy is the male counterpart of penis envy, which is the greater problem? Horney suggests that the apparently greater need of men to depreciate women is a reflection of their unconscious feelings of inferiority, due to the very limited role they play in childbirth and the raising of children (particularly breast-feeding infants, which they cannot do). In addition, the powerful creative drives and excessive ambition that are characteristic of many men can be viewed, according to Horney, as overcompensation for their limited role in parenting. Thus, as wonderful and intimate as motherhood may be, it can be a burden in the sense that the men who dominate society have turned it against women. This is, of course, an illogical state of affairs, since the children being born and raised by women are also the children of the very men who then feel inferior and psychologically threatened.

For women, one of the most significant problems that results from these development processes is a desperate need to be in a relationship with a man, which Horney addressed in two of her last papers on feminine psychology: The Overvaluation of Love (1934/1967) and The Neurotic Need for Love (1937/1967). She recognized in many of her patients an obsession with having a relationship with a man, so much so that all other aspects of life seem unimportant. While others had considered this an inherent characteristic of women, Horney insisted that characteristics such as this overvaluation of love always include a significant portion of tradition and culture. Thus, it is not an inherent need in women, but one that has accompanied the patriarchal society’s demeaning of women, leading to low self-esteem that can only be overcome within society by becoming a wife and mother. Indeed, Horney found that many women suffer an intense fear of not being normal. Unfortunately, as noted above, the men these women are seeking relationships with are themselves seeking to avoid long-term relationships (due to their own insecurities). This results in an intense and destructive attitude of rivalry between women (at least, those women caught up in this neurotic need for love). When a woman loses a man to another woman, which may happen again and again, the situation can lead to depression, permanent feelings of insecurity with regard to feminine self-esteem, and profound anger toward other women. If these feelings are repressed, and remain primarily unconscious, the effect is that the woman searches within her own personality for answers to her failure to maintain the coveted relationship with a man. She may feel shame, believe that she is ugly, or imagine that she has some physical defect. Horney described the potential intensity of these feelings as “self-tormenting.”

In 1935, just a few years after coming to America, Horney rather abruptly stopped studying the psychology of women (though her last paper on the subject was not published until 1937). Bernard Paris found the transcript of a talk that Horney had delivered that year to the National Federation of Professional and Business Women’s Clubs, which provided her reasoning for this change in her professional direction (see Paris, 1994). First, Horney suggested that women should be suspicious of any general interest in feminine psychology, since it usually represents an effort by men to keep women in their subservient position. In order to avoid competition, men praise the values of being a loving wife and mother. When women accept these same values, they themselves begin to demean any other pursuits in life. They become a teacher because they consider themselves unattractive to men, or they go into business because they aren’t feminine and lack sex appeal (Horney, cited in Paris, 1994). The emphasis on attracting men and having children leads to a “cult of beauty and charm,” and the overvaluation of love. The consequence of this tragic situation is that as women become mature, they become more anxious due to their fear of displeasing men:

…The young woman feels a temporary security because of her ability to attract men, but mature women can hardly hope to escape being devalued even in their own eyes. And this feeling of inferiority robs them of the strength for action which rightly belongs to maturity.

Inferiority feelings are the most common evil of our time and our culture. To be sure we do not die of them, but I think they are nevertheless more disastrous to happiness and progress than cancer or tuberculosis. (pg. 236; Horney cited in Paris, 1994)

The key to the preceding quote is Horney’s reference to culture. Having been in America for a few years at this point, she was already questioning the difference between the greater opportunities for women in America than in Europe (though the difference was merely relative). She also emphasized that when women are demeaned by society, this had negative consequences on men and children. Thus, she wanted to break away from any perspective that led to challenges between men and women:

…First of all we need to understand that there are no unalterable qualities of inferiority of our sex due to laws of God or of nature. Our limitations are, for the greater part, culturally and socially conditioned. Men who have lived under the same conditions for a long time have developed similar attitudes and shortcomings.

Once and for all we should stop bothering about what is feminine and what is not. Such concerns only undermine our energies…In the meantime what we can do is to work together for the full development of the human personalities of all for the sake of general welfare. (pg. 238; Horney cited in Paris, 1994)

In her final paper on feminine psychology, Horney (1937/1967) concludes her discussion of the neurotic need for love with a general discussion of the relationship between anxiety and the need for love. Of course, this is true for both boys and girls. This conclusion provided a clear transition from Horney’s study of the psychology of women to her more general perspectives on human development, beginning with the child’s need for security and the anxiety that arises when that security seems threatened.

Connections Across Cultures: Cultural Differences in Interpersonal Relationship Styles

As Horney repeatedly pointed out, neurotic behavior can only be viewed as such within a cultural context. Thus, in the competitive and individualistic Western world, our cultural tendencies are likely to favor moving against and moving away from others. The same is not true in many other cultures.

Relationships can exist in two basic styles: exchange or communal relationships. Exchange relationships are based on the expectation of some return on one’s investment in the relationship. Communal relationships, in contrast, occur when one person feels responsible for the well-being of the other person(s). In African cultures we are much more likely to find communal relationships, and interpersonal relationships are considered to be a core value amongst people of African descent (Belgrave & Allison, 2006). While there may be a tendency in Western culture to consider this dependence on others as somehow “weak,” it provides a source of emotional attachment, need fulfillment, and the influence and involvement of people in each other’s activities and lives. Tibetan Buddhist cultures have also been studied for their communal aspect. Tibetan Buddhists and Tibetan culture emphasizes caring for cousins, neighbors, relatives, and family members across the life cycle. Especially for more indigenous cultures, this communal living includes caring for animals and nature and the environment.

Cultural differences also come into play in love and marriage. In America, passionate love tends to be favored, whereas in China companionate love is favored. African cultures seem to fall somewhere in between (Belgrave & Allison, 2006). When considering the divorce rate in America, as compared to many other countries, it has been suggested that Americans marry the person they love, whereas people in many other cultures love the person they marry. In a study involving people from India, Pakistan, Thailand, Mexico, Brazil, Japan, Hong Kong, the Philippines, Australia, England, and the United States, it was found that individualistic cultures placed greater importance on the role of love in choosing to get married, and also on the loss of love as sufficient justification for divorce. For intercultural marriages, these differences are a significant, though not insurmountable, source of conflict (Matsumoto & Juang, 2004). Attempting to maintain awareness of cultural differences when relationship conflicts occur, rather than attributing the conflict to the personality of the other person, can be an important first step in resolving intercultural conflict. However, it must also be remembered that different cultures acknowledge and tolerate conflict to different extents (Brislin, 2000; Matsumoto, 1997; Okun, Fried, & Okun, 1999; for a brief discussion of intergroup dialogue and conflict resolution options, see Miller & Garran, 2008).

These cultural differences are so fundamental, that even at the level of considering basic intelligence we see the effects of these contrasting perspectives. In a study on the Kiganda culture (within the country of Uganda, in Africa), Wober (1974) found that they consider intelligence to be more externally directed than we do, and they view successful social climbing and social interaction as evidence of intelligent behavior. This matches the attitude amongst Mediterranean cultures that notable people will be devoted to a life of public service (in contrast, the word “idiot” is derived from a Greek word meaning a private man).

Thus, moving toward others would be favored much more in other cultures than it might be in the Western world. Consequently, a significant attitude and the behavior of moving toward others would be less likely to be viewed as neurotic. Such issues are, of course, very important as we interact with people of other cultures, as we may consider their behavior to be odd according to our standards. Naturally, they may be thinking the same thing about us. What is probably most important is that we learn about and experience other cultures, so that differences in customs and behavior are not surprising when they occur.

Horney’s Challenge for Psychoanalysis

One of the actions that made Horney most controversial was her willingness to challenge how psychoanalysis should be conducted with patients. In New Ways in Psychoanalysis (Horney, 1939), Horney made it very clear why she thought that psychoanalysis needed to be questioned:

My desire to make a critical re-evaluation of psychoanalytical theories had its origin in a dissatisfaction with therapeutic results. (pg. 7; Horney, 1939)

Simply put, she had asked many leading psychoanalysts questions about problems in treating her patients, and none of them could offer meaningful answers (at least, they had no meaning for Horney). In addition, a few of them, such as Wilhelm Reich, encouraged her to question orthodox psychoanalytic theory. As always, Horney did not see this as a rejection of Freud. Indeed, she felt that as she pursued new ideas, she found stronger reasons to admire the foundation that Freud had established. More importantly, she was upset that those who criticized psychoanalysis often simply ignored it, rather than looking more deeply into the valuable insights she believed it still had to offer for any therapist. As before, she saved her most serious critiques for the study of feminine psychology, though she still considered psychoanalysis with an emphasis on culture to be a valid therapeutic approach:

The American woman is different from the German woman; both are different from certain Pueblo Indian women. The New York society woman is different from the farmer’s wife in Idaho. The way specific cultural conditions engender specific qualities and faculties, in women as in men – this is what we may hope to understand. (pg. 119; Horney, 1939)

In her second book on therapy, Horney proposed something quite radical: the possibility of Self-Analysis (Horney, 1942). She considered self-analysis important for two main reasons. First, psychoanalysis was an important means of personal development, though not the only means. In this assertion, she was both emphasizing the value of psychoanalysis for many people, while at the same time saying that it wasn’t so important that it had to conducted in the orthodox manner by an extensively trained psychoanalyst, since there are many paths to self-development (e.g., good friends and a meaningful career). Second, even if many people sought traditional psychoanalysis, there simply aren’t enough psychoanalysts to go around, and it can be very expensive. So, Horney provided a book to help those willing to pursue their own self-analysis, even if they do so only occasionally (which she believed could be quite effective for specific issues). She did not suggest that self-analysis was by any means easy, but more important was the realization that it was possible. With regard to the possible criticism that self-analysts might not finish the job, that they might not delve into the darkest and most repressed areas of their psyche, she simply suggested that no analysis is ever complete. What matters more than being successful is the desire to continue (Horney, 1942). In her book on self-analysis, Horney encourages people to examine the role their attachment figures and internalized figures have on their adult behavior, and suggests friends and talking with others and journaling can help us get to know the effect of these internalized figures.

Nancy Chodorow’s Psychoanalytic Feminism and the Role of Mothering

The person best known today for attempting to combine elements of Freud’s theory with an objective perspective on a psychology of women is Nancy Chodorow (1944-present), a sociologist and psychoanalyst who has focused on the special relationship between mothers and daughters.

In 1978, Chodorow published The Reproduction of Mothering. Twenty years later, she wrote a new preface for the second edition, in which she had the advantage of looking back at both the success of her book and the criticism that it drew from some. Chodorow acknowledged that many feminists felt obliged to choose between a biologically-based psychology of women and mothering (the essential Freudian perspective) versus a view in which the psychology of women and their feelings about mothering were determined by social structure and cultural mandate. Chodorow believed that social structure and culture were important, but she insisted nonetheless that the biological differences between males and females could not be dismissed. Indeed, they lead to an essential difference in the mother-daughter relationship as compared to the mother-son relationship (Chodorow, 1999a).

According to Chodorow, when a woman becomes a mother, the most important aspect of her relationship with any daughter is the recognition that they are alike. Thus, her daughter can also become a mother someday. This special connection is felt by the daughter and incorporated into her psyche, or ego. It is important to remember that much of this is happening at an unconscious level. It is not as if women choose to favor their daughters over their sons, and it is not as if women reject their sons. Chodorow argues that it just simply happens, because of the biological similarity between females. As a consequence of this special relationship, daughters are subtly shaped in ways that lead to what we often think of as feminine attributes: a sense of self-in-relation, feeling connected to others, being able to empathize, and being embedded in or dependent on relationships. For Chodorow, the internalization of the mother-daughter relationship, from the daughter’s point of view, is the development of a most important object relation. Object relations theory is the study of how people relate to internalized images and representations of important persons in their lives. The term “objects” refers not to inanimate entities but to significant others with whom an individual relates, usually one’s mother, father, or primary caregiver. As adults, many women feel a desire to have children, which is often described as a maternal instinct or a biological drive (the feeling that their “biological clock” is ticking). As an alternative, Chodorow suggests that these feelings have instead been shaped by the unconscious fantasies and emotions associated with the woman’s internal relationship to her own mother (Chodorow, 1999a).

In contrast to the development of daughters, Chodorow suggests that sons are influenced by the essential feelings of difference conveyed by their mother. Consequently, and in contrast to women, men grow up asserting their independence, and they will be anxious about intimacy if it signals dependence on another. In addition, within the cultural framework of society, men develop a greater concern with being masculine than women are concerned with their femininity (Chodorow, 1999a).

The cultural differences between men and women, as well as the early childhood differences in their relationships with their parents, create problems for the typical family structure. Since men tend to avoid relationships, they are unlikely to completely fulfill the relational needs that women have. In addition, young girls most likely experience their relationship with their father within the context of their relationship with their mother, whereas young boys have a more direct two-person relationship with their mother (in terms of heterosexual relationships; Chodorow, 1999a). Therefore, in order for a woman to balance the relational triangle she experienced with her mother and father, and the subsequent intrapsychic object-relational structure she developed, she needs to have a child. In other words, by having children, women can “reimpose intrapsychic relational structure on the social world,” and they can relate to the father of their child in terms of a family structure they were familiar with in childhood. Furthermore, having a child recreates the intimacy a woman shared with her own mother.

Family therapy often focuses on the way children are pulled in to “triangulation” to stabilize a marriage or family. A triangle is stable, (think of a 3-legged stool) so, Triangulation occurs when an outside person is drawn into a conflicted or stressful dyad relationship (two people) in an attempt to ease tension and facilitate communication. This situation is often addressed in family therapy. Examples of triangulation could include a mother who becomes unduly close to a child to balance the lonely relationship with her husband, thus stabilizing her lonely marriage by depending on too much closeness with her child. Another example is a child who gets stomach aches when the parents start fighting. The child’s stomach aches are functional in that they stop the parents from fighting and make the parents pay attention to the child, thus stabilizing the family temporarily.

Contemporary Psychoanalysis: Object Relations Theory and the Growth of the Psychodynamic Perspective

Object relations theory contends that personality can be understood as reflecting the mental images of significant figures (especially the parents) that we form early in life in response to interactions taking place within the family (Kernberg, 2004; Wachtel, 1997). These mental images (sometimes called introjects) serve as templates for later interpersonal relationships—almost like relationship blueprints or “scripts.” So if you internalized positive introjects early in life (for example, a mental image of mom or dad as warm and accepting), that’s what you expect to occur in later relationships as well. If you internalized a mental image of mom or dad as harsh and judgmental, you might instead become a self-critical person, and feel that you can never live up to other people’s standards . . . or your own (Luyten & Blatt, 2013).

Object relations theory has increased many psychologists’ interest in studying psychodynamic ideas and concepts, in part because it represents a natural bridge between the psychodynamic perspective and research in other areas of psychology. For example, developmental and social psychologists also believe that mental representations of significant people play an important role in shaping our behavior. In developmental psychology you might read about this in the context of attachment theory (which argues that attachments—or bonds—to significant people are key to understanding human behavior; Fraley, 2002). In social psychology, mental representations of significant figures play an important role in social cognition (thoughts and feelings regarding other people; Bargh & Morsella, 2008; Robinson & Gordon, 2011).

Empirical Research on Psychodynamic Theories

Empirical research assessing psychodynamic concepts has produced mixed results, with some concepts receiving good empirical support, and others not faring as well. For example, the notion that we express strong sexual feelings from a very early age, as the psychosexual stage model suggests, has not held up to empirical scrutiny. On the other hand, the idea that there are dependent, control-oriented, and competitive personality types—an idea also derived from the psychosexual stage model—does seem useful.

Many ideas from the psychodynamic perspective have been studied empirically. Luborsky and Barrett (2006) reviewed much of this research; other useful reviews are provided by Bornstein (2005), Gerber (2007), and Huprich (2009). For now, let’s look at three psychodynamic hypotheses that have received strong empirical support.

- Unconscious processes influence our behavior as the psychodynamic perspective predicts. We perceive and process much more information than we realize, and much of our behavior is shaped by feelings and motives of which we are, at best, only partially aware (Bornstein, 2009, 2010). Evidence for the importance of unconscious influences is so compelling that it has become a central element of contemporary cognitive and social psychology (Robinson & Gordon, 2011).

- We all use ego defenses and they help determine our psychological adjustment and physical health. People really do differ in the degree that they rely on different ego defenses—so much so that researchers now study each person’s “defense style” (the unique constellation of defenses that we use). It turns out that certain defenses are more adaptive than others: Rationalization and sublimation are healthier (psychologically speaking) than repression and reaction formation (Cramer, 2006). Denial is, quite literally, bad for your health, because people who use denial tend to ignore symptoms of illness until it’s too late (Bond, 2004).

- Mental representations of self and others do indeed serve as blueprints for later relationships. Dozens of studies have shown that mental images of our parents, and other significant figures, really do shape our expectations for later friendships and romantic relationships. It’s true that you expect to be treated by others as you were treated by your parents early in life (Silverstein, 2007; Wachtel, 1997). One way this can be studied is the idea of the “family in the head“. The family in the head idea is that we have internalized representations of important people in our lives, and these internalized figures talk internally to us and influence our behavior. Even though we may not live with those persons anymore and they may not even be alive, their influence in our mind is still strong, and influences our behavior. It’s as if we have an “inner mother” or “inner father” or “inner high school teacher” that is speaking to us, even if our real life mother or these other inner figures have passed away or are not around us in real life. These internalized figures are a normal part of development and attachment, yet if they are extreme in their messages and influence, such as a strongly critical inner mother or father, this can relate to personality imbalance. Lorna Smith Benjamin her her work on interpersonal approaches to personality disorders has researched the role of these internalizations in creating personality disorders (Benjamin, 2002). Benjamin’s model suggests that a strong internalized voice or figure such as a voice of a threatening mother or father that says “you are only loveable if you act this way” can imbalance the personality and make people do extreme behaviors in order to gain the gift of love. The adult person may be trying to get the gift of love from their inner mother by acting a certain way, even if the mother has passed away. Thus Benjamin refers to these as internalized figures in contrast to real life mothers. Helping a person learn to not be overly influenced by these internalized figures is the goal of many psychoanalytic and interpersonal and cognitive therapies.

Video 1: Tiffanie on Sublimation

Vocabulary

- Ego defenses: Mental strategies, rooted in the ego, that we use to manage anxiety when we feel threatened (some examples include repression, denial, sublimation, and reaction formation). Also called defense mechanisms.

Exchange relationships are based on the expectation of some return on one’s investment in the relationship. Communal relationships, in contrast, occur when one person feels responsible for the well-being of the other person(s). Countries and regions differ in their focus on exchange relationships vs communal relationships. Tibetan Buddhists live a strongly communal life for example, caring for cousins and neighbors as if they were family.

Family in the Head: The family in the head idea is that we have internalized representations of important people in our lives, and these internalized figures talk to us and influence our behavior

-

- Id, Ego, and Superego.

- The id is the seat of drives and instincts, whereas the ego represents the logical, reality-oriented part of the mind, and the superego is basically your conscience—the moral guidelines, rules, and prohibitions that guide your behavior.

- Object relations theory

- A modern offshoot of the psychodynamic perspective, this theory contends that personality can be understood as reflecting mental images of significant figures (especially the parents) that we form early in life in response to interactions taking place within the family; these mental images serve as templates (or “scripts”) for later interpersonal relationships.

- Overvaluation of love: an idea by psychoanalyst Karen Horney that sexism and the demeaning of women’s value leads them to overvalue the experience of love and their connection to a male, usually through marriage.

- Primacy of the Unconscious

- The hypothesis—supported by contemporary empirical research—that the vast majority of mental activity takes place outside conscious awareness.

- Psychic causality

- The assumption that nothing in mental life happens by chance—that there is no such thing as a “random” thought or feeling.

- Psychosexual stage model

- Probably the most controversial aspect of psychodynamic theory, the psychosexual stage model contends that early in life we progress through a sequence of developmental stages (oral, anal, Oedipal, latency, and genital), each with its own unique mode of sexual gratification.

- Self-in-relation, feeling connected to others, being able to empathize, and being embedded in or dependent on relationships.

Self-analysis: An idea by Karen Horney and others that people can study themselves and don’t always have to use professionals, such as studying their own internalized figures and how these figures influence our behavior.

Triangulation: occurs when an outside person is drawn into a conflicted or stressful relationship in an attempt to ease tension and facilitate communication.

Womb Envy: An idea by psychoanalyst Karen Horney that men envy women’s ability to create life.

Quiz

References

- Bargh, J. A., & Morsella, E. (2008). The unconscious mind. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3, 73-79.

- Blatt, S. J., & Levy, K. N. (2003). Attachment theory, psychoanalysis, personality development, and psychopathology. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 23, 104-152.

- Bond, M. (2004). Empirical studies of defense style: Relationships with psychopathology and change. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 12, 263-278.

- Bornstein, R. F. (2010). Psychoanalytic theory as a unifying framework for 21st century personality assessment. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 27, 133-152.

- Bornstein, R. F. (2009). Heisenberg, Kandinsky, and the heteromethod convergence problem: Lessons from within and beyond psychology. Journal of Personality Assessment, 91, 1-8.

- Bornstein, R. F. (2006). A Freudian construct lost and reclaimed: The psychodynamics of personality pathology. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 23, 339-353.

- Bornstein, R. F. (2005). Reonnecting psychoanalysis to mainstream psychology: Challenges and opportunities. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 22, 323-340.

- Cramer, P. (2006). Protecting the self: Defense mechanisms in action. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Cramer, P. (2000). Defense mechanisms in psychology today: Further processes for adaptation. American Psychologist, 55, 637–646.

- Eagle, M. N. (2011). From classical to contemporary psychoanalysis: A critique and integration. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

- Elliott, A. (2002). Psychoanalytic theory: An introduction. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Erdelyi, M. H. (2004). Subliminal perception and its cognates: Theory, indeterminacy, and time. Consciousness and Cognition, 13, 73-91.

- Erdelyi, M. H. (1985). Psychoanalysis: Freud’s cognitive psychology. New York, NY: W. H. Freeman.

- Fraley, R. C. (2002). Attachment stability from infancy to adulthood: Meta-analysis and dynamic modeling of developmental mechanisms. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 6, 123-151.

- Freud, S. (1953a). The interpretation of dreams. In J. Strachey (Ed. & Trans.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vols. 4-5). London, England: Hogarth. (Original work published 1900)

- Freud, S. (1953b). Three essays on the theory of sexuality. In J. Strachey (Ed. & Trans.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 7, pp. 125–245). London, England: Hogarth. (Original work published 1905)

- Gerber, A. (2007). Whose unconscious is it anyway? The American Psychoanalyst, 41, 11, 28.

- Huprich, S. K. (2009). Psychodynamic therapy: Conceptual and empirical foundations. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

- Kandel, E. R. (1998). A new intellectual framework for psychiatry. American Journal of Psychiatry, 155, 457–469.

- Kernberg, O. F. (2004). Contemporary controversies in psychoanalytic theory, techniques, and their applications. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Levin, R., & Nielsen, T. A. (2007). Disturbed dreaming, posttraumatic stress disorder, and affect distress: A review and neurocognitive model. Psychological Bulletin, 133, 482–528.

- Luborsky, L., & Barrett, M. S. (2006). The history and empirical status of key psychoanalytic concepts. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 2, 1–19.

- Luyten, P., & Blatt, S. J. (2013). Interpersonal relatedness and self-definition in normal and disrupted personality development. American Psychologist, 68, 172–183.

- Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (2010). Culture and selves: A cycle of mutual constitution. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5, 420–430.

- McWilliams, N. (2009). Psychoanalytic diagnosis (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Oyserman, D., Coon, H. M., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 3–72.

- Robinson, M. D., & Gordon, K. H. (2011). Personality dynamics: Insights from the personality social cognitive literature. Journal of Personality Assessment, 93, 161–176.

- Silverstein, M. L. (2007). Disorders of the self: A personality-guided approach. Washington, DC: APA Books.

- Slipp, S. (Ed.) (2000). Neuroscience and psychoanalysis [Special Issue]. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis, 28, 191–395.

- Solms, M., & Turnbull, O. H. (2011). What is neuropsychoanalysis? Neuropsychoanalysis, 13, 133–145.

- Wachtel, P. L. (1997). Psychoanalysis, behavior therapy, and the relational world. Washington, DC: APA Books.

- Wilson, T. D. (2009). Know thyself. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 4, 384–389.

Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike

Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike