5 Carl Jung

This is an edited and adapted chapter by Kellan, M (2015). For full attribution see end of chapter.

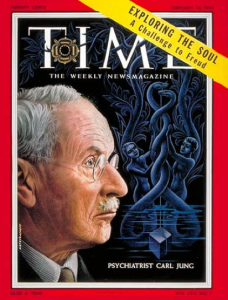

Carl Jung: Analytic Psychology

*Note: Historical personality theorists such as Jung wrote most often using the gendered term “man” rather than a word such as people or humans. To represent Jung’s historical writings accurately, quotes keep the usage of “man” and other gendered terminology. Readers can decide on their own if Jung’s thought applies more generally to other genders and class discussion will attempt to contextualize Jung’s thought with respect to gender and historical sexism.

As you read this chapter, you may realize the many ideas Jung contributed that to modern psychology. Jung is the broadest historical theorist of personality. He studied many world cultures to try to understand the universal symbols and nature of personality.

Carl Jung brought an almost mystical approach to psychodynamic theory. An early associate and follower of Freud, Jung eventually disagreed with Freud on too many aspects of personality theory to remain within a strictly Freudian perspective. Subsequently, Jung developed his own theory, which applied concepts from natural laws (primarily in physics) to psychological functioning. Jung also introduced the concept of personality types, and began to address personality development throughout the lifespan. In his most unique contribution, at least from a Western perspective, Jung proposed that the human psyche contains within itself psychological constructs developed throughout the evolution of the human species.

Jung has always been controversial and confusing. His blending of psychology and religion, as well as his openness to different religious and spiritual philosophies, was not easy to accept for many psychiatrists and psychologists trying to pursue a purely scientific explanation of personality and mental illness. Perhaps no one was more upset than Freud, whose attitude toward Jung changed dramatically over just a few years. In 1907, Freud wrote a letter to Jung in which Freud offered high praise:

…I have already acknowledged…above all that your person has filled me with trust in the future, that I now know that I am dispensable like everyone else, and that I wish for no one other or better than you to continue and complete my work. (pg. 136; cited in Wehr, 1989)

Later Freud would turn against Jung, saying his ideas were unorthodox and incorrect.

Who was this man who inspired such profound confidence from Sigmund Freud, only to later inspire such contempt? And were his theories that difficult for the psychodynamic community, or psychology in general, to accept? Hopefully, this chapter will begin to answer those questions.

A Brief Biography of Carl Jung

At the beginning of his autobiography, entitled Memories, Dreams, Reflections, Jung (1961) described his life as “a story of the self-realization of the unconscious.” Jung believed that our personality begins with a collective unconscious, developed within our species throughout time, and that we have only limited ability to control the psychic process that is our own personality. Thus, our true personality arises from within as our collective unconscious comes forth into our personal unconscious and then our consciousness. It can be helpful to view these concepts from an Eastern perspective, and it is interesting to note that “self-realization” was used in the name of the first Yoga society established in America (in 1920 by Paramahansa Yogananda).

Jung’s father, Johann Jung was a scholar of Oriental languages, studied Arabic, and was ordained a minister. In addition to being a pastor at two churches during Jung’s childhood, Johann Jung was the pastor at Friedmatt, the insane asylum in Basel. During Jung’s early childhood he did not always have the best of relationships with his parents. He considered his mother to be a good mother, but he felt that her true personality was always hidden. She spent some time in the hospital when he was three years old, in part due to problems in her marriage. Jung found this separation from his mother deeply troubling, and he became mistrustful of the spoken word “love.” Since his father was a pastor, there were often funerals and burials, all of which was very mysterious to the young Jung. In addition, his mother was considered a spiritual medium, and often helped Jung with his later studies on the occult. Perhaps most troubling of all, was Jung’s belief that his father did not really know God, but rather, had become a minister trapped in the performance of meaningless ritual (Jaffe, 1979; Jung, 1961; Wehr, 1989).

An only child until he was 9, Jung preferred to be left alone, or at least he came to accept his loneliness. Even when his parent’s guests brought their children over for visits, Jung would simply play his games alone:

…I recall only that I did not want to be disturbed. I was deeply absorbed in my games and could not endure being watched or judged while I played them. (pg. 18; Jung, 1961)

He also had extraordinarily rich and meaningful dreams, many of which were quite frightening, and they often involved deeply religious themes. This is hardly surprising, since two uncles on his father’s side of the family were ministers, and there were six more ministers on his mother’s side. Thus, he was often engaged in religious discussions at home. He was particularly impressed with a richly illustrated book on Hinduism, with pictures of Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva (the Hindu trinity of gods). Even at 6 years old, he felt a vague connection with the Hindu gods, something that once again would have an interesting influence on his later theories. These dreams led Jung into deep religious speculations, something he considered to be a secret that he could not share with anyone else (Jaffe, 1979; Jung, 1961; Wehr, 1989).

At age 12, Jung had been knocked down by another boy on the way home from school. He hit his head on a rock, and was nearly knocked out. He was so dizzy that others had to help him, and he suddenly realized that he did not have to go to school if he was ill. Consequently, he began having fainting spells any time he was sent to school or to do his homework. He missed 6 months of school due his psychological problems, and Jung loved the opportunity to spend his days exploring the world in any way he wished. He was eventually diagnosed with epilepsy, though Jung himself knew the diagnosis was ridiculous. One day he heard his father expressing great fear to a friend about what would become of Jung if he were unable to earn his own living. The reality of this statement was shocking to Jung, and “From that moment on I became a serious child.” He immediately went to study Latin, and began to feel faint. However, he consciously made himself aware of his neurosis, and cognitively fought it off. He soon returned to school, recognizing “That was when I learned what a neurosis is” (Jaffe, 1979; Jung, 1961; Wehr, 1989).

As he continued through school, his personal life continued to be quite strange. He began to believe that he was two people, one having lived 100 years earlier. He also had heated religious debates with his father. Fueling his courage during these debates was his belief that a vision had led to his understanding of true spirituality:

One fine summer day that same year I came out of school at noon and went to the cathedral square. The sky was gloriously blue, the day one of radiant sunshine. The roof of the cathedral glittered, the sun sparkling from the new, brightly glazed tiles. I was overwhelmed by the beauty of the sight, and thought: “The world is beautiful and the church is beautiful, and God made all this and sits above it far away in the blue sky on a golden throne and …” Here came a great hole in my thoughts, and a choking sensation. I felt numbed, and knew only: “Don’t go on thinking now! Something terrible is coming, something I do not want to think, something I dare not even approach. Why not? Because I would be committing the most frightful of sins. What is the most terrible sin? Murder? No, it can’t be that. The most terrible sin is the sin against the Holy Ghost, which cannot be forgiven. Anyone who commits that sin is damned to hell for all eternity. That would be very sad for my parents, if their only son, to whom they are so attached, should be doomed to eternal damnation. I cannot do that to my parents. All I need do is not go on thinking.” (pg. 36; Jung, 1961)

However, Jung was not able to ignore his vision. He was tormented for days, and spent sleepless nights wondering why he would have to think something unforgivable as a result of praising God for the beauty of all creation. His mother saw how troubled he was, but Jung felt that he could not dare confide in her. Finally, he decided that it was God’s will that he should face the meaning of this vision:

I thought it over again and arrived at the same conclusion. “Obviously God also desires me to show courage,” I thought. “If that is so and I go through with it, then He will give me His grace and illumination.”

I gathered all my courage, as though I were about to leap forthwith into hell-fire, and let the thought come. I saw before me the cathedral, the blue sky. God sits on His golden throne, high above the world – and from under the throne an enormous turd falls upon the sparkling new roof, shatters it, and breaks the walls of the cathedral asunder. (pg. 39; Jung 1961)

Jung was overjoyed by his understanding of this vision. He believed that God had shown him that what mattered in life was doing God’s will, not following the rules of any man, religion, or church. This was what Jung felt his own father had never come to realize, and therefore, his father did not know the “immediate living God.” This conviction that one should pursue truth, rather than dogma, was an essential lesson that returned when Jung faced his dramatic split with Sigmund Freud.

After attending medical school and studying psychiatry, in 1906, Jung sent Freud a copy of his book The Psychology of Dementia Praecox (an earlier term for schizophrenia), which Freud found quite impressive. The two met in February, 1907, and talked for nearly 13 straight hours. According to Jung, “Freud was the first man of real importance I had encountered…no one else could compare with him.” Very quickly, as evidenced in the letters quoted at the beginning of this chapter, Freud felt that Jung would become the leader of the psychoanalytic movement. In 1909, Jung’s psychoanalytic practice was so busy that he resigned from the Burgholzli clinic, and he traveled to America with Freud. During this trip the two men spent a great deal of time together. It quickly became evident to Jung that he could not be the successor that Freud was seeking; Jung had too many differences of opinion with Freud. More importantly, however, Jung described Freud as neurotic, and wrote that the symptoms were sometimes highly troublesome (though Jung failed to identify those symptoms). Freud taught that everyone was a little neurotic, but Jung wanted to know how to cure neuroses:

Apparently neither Freud nor his disciples could understand what it meant for the theory and practice of psychoanalysis if not even the master could deal with his own neurosis. When, then, Freud announced his intention of identifying theory and method and making them into some kind of dogma, I could no longer collaborate with him; there remained no choice for me but to withdraw. (pg. 167; Jung, 1961)

Clearly Jung could not accept a dogmatic approach to psychoanalysis, since he believed that God Himself had told Jung not to follow any rigid system of rules. Even worse, this was when Jung first published his “discovery” of the collective unconscious. Freud wholly rejected this concept, and Jung felt that his creativity was being rejected. He offered to support Freud in public, while extending honest opinions in so-called “secret letters.” Freud wanted none of it. Almost as quickly as their relationship had grown, it fell apart (Jaffe, 1979; Jung, 1961; Wehr, 1989).

The loss of his relationship with Freud, following the loss of his father, led Jung in a period of personal crisis. He resigned his position at the University of Zurich, and began a lengthy series of experiments in order to understand the fantasies and dreams that arose from his unconscious. The more he studied these phenomena, the more he realized they were not from his own memories, but from the collective unconscious. He was particularly curious about mandala drawings, which date back thousands of years in all cultures. He studied Christian Gnosticism, alchemy, and the I Ching (or: Book of Changes). After meeting Richard Wilhelm, an expert on Chinese culture, Jung studied more Taoist philosophy, and he wrote a glowing foreword for Wilhelm’s translation of the I Ching (Wilhelm, 1950). These extraordinarily diverse interests led Jung to seek more in-depth knowledge from around the world. He traveled first to North Africa, then to America (to visit Pueblo Indians in New Mexico), next came East Africa (Uganda and Kenya), and finally India. Jung made every effort to get away from civilized areas, which might have been influenced by other cultures, in order to get a more realistic impression of the local culture, and he was particularly successful in this regard in meeting gurus in India (Jaffe, 1979; Jung, 1961; Wehr, 1989).

Carl Jung died at home in 1961, in Kusnacht, Switzerland, at the age of 85. As psychologists today examine more deeply the relationship between Eastern and Western perspectives, it may be that Jung’s legacy has yet to be fulfilled.

Discussion Question: Even as a child, Jung had vivid dreams that he believed were giving him insight and guidance for the future. Have you ever had dreams so vivid, dreams that left such a powerful impression on you, that you felt they must have some special meaning? How did you respond, and what consequences, if any, followed your responses?

Placing Jung in Context: A Psychodynamic Enigma

Carl Jung holds an extraordinary place in the histories of psychiatry and psychology. Having already been an assistant to the renowned psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler, he went to Vienna to learn more about the fledgling science of psychoanalysis. He became Freud’s hand-picked heir to the psychoanalytic throne, and was one of the psychiatrists who accompanied Freud to America. Later, however, as he developed his own theories, he parted ways with Freud. Freud eventually came to describe Jung’s theories as incomprehensible, and Freud praised other psychiatrists who also opposed Jung’s ideas.

The most dramatic contribution that Jung made to psychodynamic thought was his concept of the collective unconscious, which can be thought of as structures of the unconscious mind which are shared among people, or patterns and reactions in the mind that all people have in common across the world. These patterns do not come from childhood experiences. We are born with similar patterns of thought, emotion, and reaction. For example all cultures have something in common in the way they react to “hero” or to the concept of “mother”. Jung traveled extensively, including trips to Africa, India, and the United States (particularly to visit the Pueblo Indians in New Mexico), and he studied the cultures in those places. He also observed many basic similarities between different cultures that would arise in stories and fairy tales. Those similarities across people and cultures led Jung to propose the collective unconscious. How else could so many significant cultural similarities have arisen within separate and distant lands? In modern days, when people watch movies or read books, you can watch the similarities of how people react to things such as a sunset and wonder if Jung might be right that we are born with shared memories that cause us to react in certain ways across the world.

Initially Jung’s theories had more influence on art, literature, and anthropology than they did on psychiatry and psychology. More recently, however, cognitive-behavioral theorists have begun to explore mindfulness as an addition to more traditional aspects of cognitive-behavioral therapies. As psychologists today study concepts from Yoga and Buddhism that are thousands of years old, Jung deserves the credit for bringing such an open-minded approach to the modern world of psychotherapy. Many famous and influential people admired Jung’s work, including psychiatrist Viktor Frankl, psychologist Erich Fromm, the authors Hermann Hesse and H. G. Wells, and Nobel Laureate (Physics) Wolfgang Pauli (for a number of interesting testimonials see Wehr, 1989). In addition, Jung was influential in the founding of Alcoholics Anonymous.

Basic Concepts

In order to distinguish his own approach to psychology from others that had come before, Jung felt that he needed a unique name. Freud, of course, had chosen the term “psychoanalysis,” whereas Alfred Adler had chosen “individual psychology.” Since Jung admired both men and their theories, he chose a name intended to encompass not only their approaches, but others as well. Thus, he chose to call his approach analytical psychology (Jung, 1933).

Analytical psychology, as presented by Jung, addresses the question of the psyche in an open-minded way. He laments the overly scientific approach of the late 1800s and efforts to explain away the psyche as a mere epiphenomenon of brain function. Curiously, that debate remains with us today, and is still unanswered in any definitive way. Jung did not accept the suggestion that the psyche must come from the activity of the brain. This allowed him to consider the possibility of a collective unconscious, and fit well with his acceptance of the wisdom of Eastern philosophers. Indeed, Jung suggests that psychology will find truth only when it accepts both Eastern and Western, as well as both scientific and spiritual, perspectives on the psyche (Jung, 1933).

Dynamic Psychic Energy

An important element of Jung’s conception of the psyche and libido is found in the nature of opposites. Indeed, all of nature is composed of opposites:

…The concept of energy implies that of polarity, since a current of energy necessarily presupposes two different states, or poles, without which there can be no current. Every energic phenomenon…consists of pairs of opposites: beginning and end, above and below, hot and cold, earlier and later, cause and effect, etc. The inseparability of the energy concept from that of polarity also applies to the concept of libido. (pg. 202; Jung, 1971)

…opposites are the ineradicable and indispensable preconditions of all psychic life… (pg. 170; Jung, 1970)

In accordance with this view, Jung felt that the psyche sought balance, much like the concept of entropy from the field of physics. Entropy, in simple terms, is a thermodynamic principle that all energy within a system (including the universe) will eventually even out. Jung applied the principle of dynamic psychic energy to motivation, believing that we are driven forward through our lives in such a way that we might reduce the imbalance of psychic energy between opposing pairs of emotions (such as love and hate; Jarvis, 2004; Jung, 1971). Getting to know different or opposing parts of ourselves and the world was the way our personality grew “whole”. Psychic dynamic energy included the idea that we should listen to different points of view inside ourselves, and outside ourselves, because opposing views usually had some truth to them and were trying to form a larger “whole” and a larger “whole person”. The person who could listen to various points of view such as love and hate within themselves, and balance these out, was a well-developed individual. The person who was constantly turning against other points of view was likely to be imbalanced and unhappy. Jung however did account for the fact that some people were freedom fighters or activists that were engaged in changing society, but even for activists they needed to examine their “opposites” so they could determine if they were fighting an internal battle or reaction to something from their past, or were they fighting legitimate oppression in the world.

Dreams and Dream Analysis. Jung believed that our dreams had important symbols in them, and could teach us to be more whole as a person. Dream analysis was the act of analyzing our dream symbols and their meanings. Dream analysis can be done in different ways, and Jung had a particular view of how to do dream analysis. Dreams were trying to communicate information to us. Jung believed that dreams could guide our future behavior, because of their profound relationship to the past, and their profound influence on our conscious mental life. Jung proposed that dreams can tell us something about the development and structure of the human psyche, and that dreams have evolved with our species throughout time. Since consciousness is limited by our present experience, dreams help to reveal much deeper and broader elements of our psyche than we can be aware of consciously. As such, dreams cannot easily be interpreted. Jung rejected the analysis of any single dream, believing that they belong within a series. He also rejected trying to learn dream analysis from a book. When done properly, however, dream analysis can provide unparalleled realism (see Jacobi & Hull, 1970; Jung, 1933):

Jung wrote that “dreams are the natural reaction of the self-regulating psychic system.” When we dream, the ongoing effort of our psyche to balance itself takes over, and the dreams counteract what we have done to imbalance our psychological selves. Thus, it is within the context of dreams, not the details, that meaning is to be found (Jung, 1959a, 1968).

Stated another way, dreams are trying to show us parts of our psyche that we are unaware of, and teach us to be more whole and to have psychic balance. For example if we dream of a dragon shooting fire from its mouth, over time we may begin to know that this fiery power of the dragon is somehow related to us. Perhaps we are passive in our ways, and dreams of fiery dragons begin to get us in touch with our fiery nature, which we have otherwise repressed or not expressed.

Jung’s theories have been developed by more recent theorists. For example Arnold Mindell PhD, a physicist and psychologist has written extensively about how the materials of dreams is reflected in other perceptual channels of experience. Jung was suggesting that dreams were trying to bring parts of our psyche to awareness (Mindell, 2011). Mindells calls his concept the Dreambody and suggests that body symptoms, as well as dreams, are trying to bring information to our awareness. Mindell gives the example of a woman who dreams of a tree on fire. The woman is also dealing with inflammatory arthritis. As the woman describes the dream as well as the arthritis, both have a fiery quality. Consistent with Jung’s ideas, the “fiery” part of this woman’s nature may be trying to come to awareness.

By talking about the information in our body symptoms we will arrive at similar information to what we dreamed about.

Mindell has expanded his work to include relationship problems and world problems as ways perceptual channels that bring psychic information to our awareness. For example a conflict in a relationship can reflect the same information we dreamed about last night. Dreams and body symptoms mirror or reflect similar information.

Discussion Question: Jung believed that the source of our motivation was a psychological drive to achieve balance (the effect of entropy on the psyche). Have you ever felt that you were being pushed or pulled in the wrong direction, or in too many directions at once, and simply wanted to achieve some balance in your life? In contrast, have there been times that your life was unfulfilling, and you needed something more in order to feel whole?

The Unconscious Mind

Perhaps Jung’s most unique contribution to psychology is the distinction between a personal unconscious and a collective unconscious. Whereas the contents of the personal unconscious are acquired during the individual’s lifetime, the contents of the collective unconscious are invariably archetypes or images that were present from the beginning. (pp. 7-8; Jung, 1959c). Jung used the term complex which is similar to the modern term schema, to describe the collective unconscious. Jung was trying to communicate that we have a complex or cluster or emotions and images related to a concept. Some of those emotions and images are from our personal history, yet some seem to be not from us — they were with us from the start or they come from around us. In that sense, Jung suggested “people don’t have ideas, ideas have people” which meant that we think we are being carried through life based on our own decisions, yet there is an aspect of a “bigger power” that is directing our life as well. Jung felt it was very important to be in contact with this sense of a bigger power (Jung, 1959c).

Thus, according to Jung, the collective unconscious is a reservoir of psychic resources common to all humans (something along the lines of psychological instinct). These psychic resources, known as archetypes, are passed down through the generations of a culture, but Jung considered them to be inherited, not learned. As generation after generation experienced similar phenomena, the archetypal images were formed. Despite cultural differences, the human experience has been similar in many ways throughout history.

It is important to note that archetypal images are considered to be ancient. Jung has referred to archetypes as primordial images, “impressed upon the mind since of old” (Jung, 1940). Archetypes have been expressed as myths and fables, some of which are thousands of years old even within recorded history. As the eternal, symbolic images representing archetypes were developed, they naturally attracted and fascinated people. That, according to Jung, is why they have such profound impact, even today, in our seemingly advanced, knowledgeable, and scientific societies.

| Table 4.1: Common Archetypes in Jung’s Theory of the Collective Unconscious* | ||

| Self | Integration and wholeness of the personality, the center of the totality of the psyche; symbolically represented by, e.g., the mandala, Christ, or by helpful animals (such as Rin Tin Tin and Lassie or the Hindu monkey god Hanuman) | |

| Shadow | The dark, inferior, emotional, and immoral aspects of the psyche; symbolically represented by, e.g., the Devil (or an evil character such as Dracula), dragons, monsters (such as Godzilla) | |

| Anima | Strange, wraithlike image of an idealized women, yet contrary to the masculinity of the man, draws the man into feminine (as defined by gender roles) behavior, always a supernatural element; symbolically represented by, e.g., personifications of witches, the Greek Sirens, a femme fatale, or in more positive ways as the Virgin Mary, a romanticized beauty (such as Helen of Troy) or a cherished car | |

| Animus | A source of meaning and power for women, it can be opinionated, divisive, and create animosity toward men, but also creates a capacity for reflection, deliberation, and self-knowledge; symbolically represented by, e.g., death, murderers (such as the pirate Bluebeard, who killed all his wives), a band of outlaws, a bewitched prince (such as the beast in “Beauty and the Beast”) or a romantic actor (such as Rudolph Valentino) | |

| Persona | A protective cover, or mask, that we present to the world to make a specific impression and to conceal our inner self; symbolically represented by, e.g., a coat or mantle | |

| Hero | One who overcomes evil, destruction, and death, often has a miraculous but humble birth; symbolically represented by, e.g., angels, Christ the Redeemer, or a god-man (such as Hercules) | |

| Wise Old Man | Typically a personification of the self, associated with saints, sages, and prophets; symbolically represented as, e.g., the magician Merlin or an Indian guru | |

| Trickster | A childish character with pronounced physical appetites, seeks only gratification and can be cruel and unfeeling; symbolically represented by, e.g., animals (such as

Brer Rabbit, Wile E. Coyote or, often, monkeys) or a mischievous god (such as the Norse god Loki) |

The Shadow

Jung described the shadow in many ways. At times Jungian psychology is referred to as shadow psychology. One way Jung described the shadow was (Jung, 1940, 1959c) that the shadow encompasses desires and feelings that are not acceptable to society or the conscious psyche. This might include aggression, lust, and other parts of a person that they are less comfortable showing to others. With effort the shadow can be somewhat assimilated into the conscious personality, but portions of it are highly resistant to moral control. Portions of the shadow have a transpersonal power to them, a power beyond what most people can imagine. Most people, Jung thought, do not try to be aware of their shadow. Yet the shadow had great creative power. As a result of not being in touch with our shadow aspects of our psyche, we tend to project those thoughts, feelings, or emotions onto other people. By projecting the on to other people and not identifying with them and saying “this is me that acts this way and feels these things”, the shadow can take on a life of its own and make us no longer approaching situations realistically. We also lose the creativity contained in the images and energies of the shadow. For example if we repress “lust” and sexual desires, we lose passion for life. Jung’s therapy tried to help people integrate their shadow aspects in ways that were creative and not destructive. Lust and sexual desires were about sex, yet they could also be about passion and creativity in a person’s broader life.

Connections Across Cultures: Symbolism Throughout Time and Around the world

Near the end of Jung’s life, he was asked to write a book that might make his theories more accessible to common readers. Jung initially refused, but then he had an interesting dream, receiving advice from his unconscious psyche that he should reconsider his refusal:

…He dreamed that, instead of sitting in his study and talking to the great doctors and psychiatrists who used to call on him from all over the world, he was standing in a public place and addressing a multitude of people who were listening to him with rapt attention and understanding what he said… (pg. 10; John Freeman, in his introduction to Man and His Symbols, Jung et al., 1964)

Jung then agreed to write the book that became known as Man and His Symbols, but only if he could hand-pick the co-authors who would help him. Jung supervised every aspect of the book, which was nearly finished when he died. Written purposefully to be easily understood by a wide audience, the book presents an astonishingly wide variety of symbolism from art, archaeology, myth, and analysis within the context of Jung’s theories. Many of the symbols were represented in dreams, and symbolic dreams are the primary means by which our unconscious psyche communicates with our conscious psyche, or ego. It is extraordinary to see how similar such symbolism has been throughout time and across cultures, even though each individual example is unique to the person having the dream or expressing themselves openly.

Symbols, according to Jung, are terms, names, images, etc. that may be familiar in everyday life, but as symbols they come to represent something vague and unknown, they take on meaning that is hidden from us. More specifically, they represent something within our unconscious psyche that cannot ever be fully explained. Exploring the meaning will not unlock the secrets of the symbol, because its meaning is beyond reason. Jung suggests that this should not seem strange, since there is nothing that we perceive fully. Our eyesight is limited, as is our hearing. Even when we use tools to enhance our senses, we still only see better, or hear better. We don’t comprehend the true nature of visual objects or sounds, we only experience them differently, within our psychic realm as opposed to their physical reality. And yet, the symbols created by our unconscious psyche are very important, since the unconscious is at least half of our being, and it is infinitely broader than our conscious psyche (Jung et al., 1964).

Jung believed that the symbols created in dreams have a deeper meaning than Freud recognized. Freud believed that dreams simply represent the unconscious aspects of one’s psyche. Jung believed, however, that dreams represent a psyche all their own, a vast and ancient psyche connected to the entire history of humanity (the collective unconscious). Therefore, dreams can tell a story of their own, such as Jung’s dream encouraging him to write a book for a common audience. Thus, his dream did not reflect some underlying neurosis connected to childhood trauma, but rather, his unconscious psyche was pushing him forward, toward a sort of wholeness of self by making his theories more readily accessible to those who are not sufficiently educated in the wide variety of complex topics that are typically found in Jung’s writings. By virtue of the same reasoning, Jung considered dreams to be quite personal. They could not be interpreted with dream manuals, since no object has any fixed symbolic meaning.

What makes the symbolism within dreams, as well as in everyday life, most fascinating, however, is how common it is throughout the world, both in ancient times and today. In their examination of symbols and archetypes, Jung and his colleagues offer visual examples from: Egypt, England, Japan, the Congo, Tibet, Germany, Belgium, the United States, Bali, Haiti, Greece, Switzerland, Spain, Italy, Cameroon, Java, France, Kenya, India, Sweden, Russia, Poland, Australia, China, Hungary, Malaysia, Borneo, Finland, the Netherlands, Rhodesia, Israel, Saudi Arabia, Scotland, Ireland, Brazil, Monaco, Burma, Bolivia, Cambodia, Denmark, Macedonia, and Peru, as well as from Mayan, Celtic, Babylonian, Persian, Navaho, and Haidu cultures. There are also many Biblical references. It would be safe to say that no one else in the history of psychology has so clearly demonstrated the cross-cultural reality of their theory as is the case with Carl Jung.

Of course, as with dreams, many of these symbols are unique to the culture in which they have arisen. Therefore, it takes a great deal of training and experience for a psychotherapist to work with patients from different cultures. Nonetheless, the patterns represent the same basic concepts, such as self, shadow, anima, animus, hero, etc. Once recognized in their cultural context, the analyst would have a starting point from which to begin working with their patient, or the artist would understand how to influence their audience. One important type of art that relies heavily on cultural images and cues is advertising. Cultural differences can create problems for companies pursuing global marketing campaigns. Jung’s theory suggests that similarities in how we react to certain archetypal themes should be similar in different countries, but of course the images themselves must be recognizable, and we may still be a long way from understanding those fundamental images:

…Our actual knowledge of the unconscious shows that it is a natural phenomenon and that, like Nature herself, it is at least neutral. It contains all aspects of human nature – light and dark, beautiful and ugly, good and evil, profound and silly. The study of individual, as well as of collective, symbolism is an enormous task, and one that has not yet been mastered. (pg. 103; Jung et al., 1964)

Personality Types

One of Jung’s most practical theories, and one that has been quite influential, is his work on personality types. Jung had conducted an extensive review of the available literature on personality types, including perspectives from ancient Brahmanic conceptions taken from the Indian Vedas (see below) and types described by the American psychologist William James. In keeping with one of Jung’s favorite themes, James had emphasized opposing pairs as the characteristics of his personality types, such as rationalism vs. empiricism, idealism vs. materialism, or optimism vs. pessimism (see Jung, 1971). Based on his research and clinical experience, Jung proposed a system of personality types based on attitude-types and function-types (more commonly referred to simply as attitudes and functions). Once again, the attitudes and functions are based on opposing ways of interacting with one’s environment.

The two attitude-types are based on one’s orientation to external objects (which includes other people). The introvert is intent on withdrawing libido (energy) from objects, as if to ensure that the object can have no power over the person. In contrast, the extravert extends libido toward an object, establishing an active relationship. Jung considered introverts and extraverts to be common amongst all groups of people, from all walks of life. Today, most psychologists acknowledge that there is a clear genetic component to these temperaments (Kagan, 1984, 1994; Kagan, Kearsley, & Zelazo 1978), a suggestion proposed by Jung as well (Jung, 1971).

Jung’s four functions describe ways in which we orient ourselves to the external environment, given our basic tendency toward introversion or extraversion. The first opposing pair of functions is thinking vs. feeling. Thinking involves intellect, it tells you what a thing is, whereas feeling is values-based, it tells what a thing is worth to you. For example, if you are trying to choose classes for your next semester of college, perhaps you need to choose between a required general education course as opposed to a personally interesting course like Medical First Responder or Interior Design. If you are guided first by thinking, you will probably choose the course that fulfills a requirement, but if you are guided by feeling, you may choose the course that satisfies your more immediate interests. The second opposing pair of functions is sensing vs. intuition. Sensing describes paying attention to the reality of your external environment, it tells you that something is. In contrast, intuition incorporates a sense of time, and allows for hunches. Intuition may seem mysterious, and Jung freely acknowledges that he is particularly mystical, yet he offers an interesting perspective on this issue:

…Intuition is a function by which you see round corners, which you really cannot do; yet the fellow will do it for you and you trust him. It is a function which normally you do not use if you live a regular life within four walls and do regular routine work. But if you are on the Stock Exchange or in Central Africa, you will use your hunches like anything. You cannot, for instance, calculate whether when you turn round a corner in the bush you will meet a rhinoceros or a tiger – but you get a hunch, and it will perhaps save your life… (pg. 14; Jung, 1968)

The two attitudes and the four functions combine to form eight personality types. Jung described a so-called cross of the functions, with the ego in the center being influenced by the pairs of functions (Jung, 1968). Considering whether the ego’s attitude is primarily introverted or extraverted, one could also propose a parallel pair of crosses. Jung’s theory on personality types has proven quite influential and led to the development of two well-known and very popular instruments used to measure one’s personality type, so that one might then make reasoned decisions about real-life choices.

In 1923, Katharine Briggs and her daughter Isabel Briggs Myers learned of Jung’s personality types and became quite interested in his theory. After spending 20 years observing individuals of different types, they added one more pair of factors based on a person’s preference for either a more structured lifestyle, called judging, or a more flexible or adaptable lifestyle, called perceiving. There were now, according to Briggs and Myers, sixteen possible personality types. In the 1940s, Isabel Myers began developing the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) in order to help people learn about their personality type. To provide just one example of an MBTI profile, an individual who is extraverted and prefers sensing, thinking, and judging (identified by the initials ESTJ) would be described as: “Practical, realistic, matter-of-fact. Decisive, quickly move to implement decisions. Organize projects and people to get things done…Forceful in implementing their plans” (Myers, 1993; Myers & McCaulley, 1985; see also the website for the Myers & Briggs Foundation, at www.myersbriggs.org). While it is relatively easy to find shortcut tests or variations of the MBTI online, if one plans to make any meaningful decisions based on their personality type they should consult a trained MBTI administrator. What sort of decision might one make? The MBTI has become a popular tool for looking at career choices and workplace relationships. A number of popular books, such as Do What You Are (Tieger & Barron-Tieger, 2001) and Type Talk at Work (Kroeger, Thuesen, & Rutledge, 2002), are available that provide information intended to help people choose satisfying careers and be successful in complex work environments. In addition to its use in career counseling, the MBTI has been used in individual counseling, marriage counseling, and in educational settings (Myers, 1993; Myers & McCaulley, 1985; Myers & Myers, 1980).

Personality Development

Jung believed that “everyone’s ultimate aim and strongest desire lie in developing the fullness of human existence that is called personality” (Jung, 1940). However, he lamented the misguided attempts of society to educate children into their personalities. Not only did he doubt the abilities the average parent or average teacher to lead children through the child’s personality development, given their own personal limitations, he considered it a mistake to expect children to act like young adults:

It is best not to apply to children the high ideal of education to personality. For what is generally understood by personality – namely, a definitely shaped, psychic abundance, capable of resistance and endowed with energy – is an adult ideal…No personality is manifested without definiteness, fullness, and maturity. These three characteristics do not, and should not, fit the child, for they would rob it of its childhood. (pp. 284-285; Jung, 1940)

This is not to suggest that childhood is simply a carefree time for children:

No one will deny or even underestimate the importance of childhood years; the severe injuries, often lasting through life, caused by a nonsensical upbringing at home and in school are too obvious, and the need for reasonable pedagogic methods is too urgent…But who rears children to personality? In the first and most important place we have the ordinary, incompetent parents who are often themselves, all their lives, partly or wholly children. (pg. 282; Jung, 1940)

So, if childhood is a critical time, but most adults never grow up themselves, what hope does Jung see for the future? The answer is to be found in midlife. According to Jung, the middle years of life are “a time of supreme psychological importance” and “the moment of greatest unfolding” in one’s life (cited in Jacobi & Hull, 1970). In keeping with the ancient tradition of the Vedic stages of life, from Hindu and Indian culture, the earlier stages of life are about education, developing a career, having a family, and serving one’s proper role within society:

Man has two aims: The first is the aim of nature, the begetting of children and all the business of protecting the brood; to this period belongs the gaining of money and social position. When this aim is satisfied, there begins another phase, namely, that of culture. For the attainment of the former goal we have the help of nature, and moreover of education; but little or nothing helps us toward the latter goal… (pg. 125; Jung, cited in Jacobi & Hull, 1970)

So where does one look for the answers to life? Obviously, there is no simple answer to that question, or rather, than are many answers to that question. Some pursue spiritual answers, such as meditating or devoting themselves to charitable causes. Some devote themselves to their children and grandchildren, others to gardening, painting, or woodworking. The answer for any particular individual is based on that person’s individuation.

Individuation is the process by which a person actually becomes an “individual,” differentiated from all other people. It is not to be confused with the ego, or with the conscious psyche, since it includes aspects of the personal unconscious, as influenced by the collective unconscious. Jung also described individuation as the process by which one becomes a “whole” person. To some extent, this process draws the individual away from society, toward being just that, an individual. However, keeping in mind the collective unconscious, Jung believed that individuation leads to more intense and broader collective relationships, rather than leading to isolation. This is what is meant by a whole person, one who successfully integrates the conscious psyche, or ego, with the unconscious psyche. Jung also addresses the Eastern approaches, such as meditation, as being misguided in their attempts to master the unconscious mind. The goal of individuation is wholeness, wholeness of ego, unconscious psyche, and community (Jung, 1940, 1971):

Personality Theory in Real Life: Synchronicity – Coincidence or an Experience with Mystical Spirituality?

Many people are deeply religious and many others consider themselves to be just as deeply spiritual, though not connected to any specific religion. As important as religion and spirituality are in the lives of many people, psychology has tended to avoid these topics, primarily because they do not lend themselves readily to scientific investigation. Jung certainly did not avoid these topics, and he studied a wide range of spiritual topics. For example, he wrote the foreword for Richard Wilhelm’s translation of the I Ching (Wilhelm, 1950), he wrote psychological commentary for a translation of The Tibetan Book of the Great Liberation (Evans-Wentz & Jung, 1954), he discussed the psychology of evil in Answer to Job (Jung, 1954), he wrote about Gnostic traditions at length (see Segal, 1992), and one of the volumes of his collected works is entitled Psychology and Religion: West and East (Jung, 1958). In addition to his varied spiritual interests, Jung became interested in psychological phenomena that could not be explained in scientific terms. Such phenomena do not necessarily require a spiritual explanation, but in the absence of any other way to explain them, they are often thought of in spiritual terms. One such topic is synchronicity.

Jung uses the term synchronicity to describe the “coincidence in time of two or more causally unrelated events which have the same or a similar meaning” (Jung & Pauli, 1955). In particular, it refers to the simultaneous occurrence of a particular psychic state with one or more external events that have a meaningful parallel to one’s current experience or state of mind. Jung wrote that he was amazed by how many people have had experiences of synchronicity.

Before dismissing synchronicity as non-scientific, keep in mind the circumstances that led Jung to this theory. In addition to personally knowing Wolfgang Pauli, Jung also knew Nils Bohr and Albert Einstein (both of whom, like Pauli, had won a Nobel Prize in physics). Although these men are considered among the greatest scientists of modern times, Einstein perhaps the greatest, consider some of their theories. For instance, Einstein proposed that time isn’t time, it’s relative, except for the speed of light, which alone is always constant. In recent years, experimental physicists have exceeded the speed of light, broken Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle (which, by definition, couldn’t be broken), and proposed that it might be possible to get something colder than absolute zero. How can we accept things that cannot be observed or proved as scientific, while rejecting something that Jung and many others have observed time and time again? Jung was impressed by the possibility of splitting atoms, and wondered if such a thing might be possible with the psyche. As physics suggested strange new possibilities, Jung held out the same hope for humanity (Progoff, 1973).

Regardless of whether the strangest of Jung’s theories are ever proven right or wrong, at the very least they provide an opportunity for interesting discussions! There also happens to be another well-known person in the history of psychology who has experienced synchronicity and who talked about many of her patients having had out-of-body and near-death experiences: Elisabeth Kubler-Ross. In her book On Children and Death (Kubler-Ross, 1983), Kubler-Ross describes even more serious concerns than Jung about discussing this topic, but as with Jung, she has also met many, many patients who have had these experiences:

…I have been called every possible name, from Antichrist to Satan himself; I have been labeled, reviled, and otherwise denounced…But it is impossible to ignore the thousands of stories that patients – children and adults alike – have shared with me. These illuminations cannot be explained in scientific language. Listening to these experiences and sharing many of them myself, it would seem hypocritical and dishonest to me not to mention them in my lectures and workshops. So I have shared all of what I have learned from my patients for the last two decades, and I intend to continue to do so. (pg. 106; Kubler-Ross, 1983)

Discussion Question: Jung studied and wrote about topics as diverse as alchemy, astrology, flying saucers, ESP, the prophecies of Nostradamus, and synchronicity. Does this make it difficult for you to believe any of his theories? If you don’t believe anything about any of these topics, are you still able to find value in other theories proposed by Jung?

A Final Note on Carl Jung

It can be something of a challenge to view Jung’s work as psychological. It lends itself more readily to, perhaps, the study of the humanities, with elements of medieval pseudo-science, Asian culture, and native religions (an odd combination, to be sure). With titles such as Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self (Jung, 1959c) and Mysterium Conjunctionis: An Inquiry into the Separation and Synthesis of Psychic Opposites in Alchemy (Jung, 1970), Jung is not exactly accessible without a wide range of knowledge in areas other than psychology. Alchemy was of particular interest to Jung, but not in terms of turning base metals into gold (alchemy is a strange mixture of spirituality and chemistry). Rather, Jung believed that psychology could find its base in alchemy, and that it was the collective unconscious that came forth in the ongoing human effort to understand the nature of matter (Jaffe, 1979; Jung, 1961; Wehr, 1989). He even went so far as to write about flying saucers, the astrological seasons of time, and the prophesies of Nostradamus (Jung, 1959c; Storr, 1983).

And yet, Jung addressed some very important and interesting topics in psychology. His theory of psychological types is reflected in trait descriptions of personality and corresponding trait tests, such as Cattell’s 16-PF and the MMPI. The value Jung placed on mid-life and beyond, based largely on the ancient Vedic stages of life, suggests that one is not doomed to the negative alternative in Erikson’s final psychosocial crises. So Jung’s personal interests, and his career as a whole, straddled the fence between surreal and practical. He may always be best-known for his personal relationship with Freud, brief as it was, but the blending of Eastern and Western thought is becoming more common in psychology. So perhaps Jung himself will become more accessible to the field of psychology, and we may find a great deal to be excited about in his curious approach to psychodynamic theory.

Videos 2: Face to Face with Carl Jung in 1959

Vocabulary

Collective Unconscious, a mysterious reservoir of psychological constructs common to all people. Jung believed this was the part of the unconscious mind which is derived from ancestral memory and experience and is common to all humankind, as distinct from the individual’s personal unconscious.

Dynamic psychic energy: Jung’s idea that our personality is trying to balance itself. It does this through the opposition of parts. For example having an “aggressive” part inside ourselves and a “passive” part inside ourselves, would eventually cause us to develop a balanced self that is not too aggressive and not too passive. Getting to know different or opposing parts of ourselves and the world was the way our personality grew “whole” and we became wise and well-developed people.

Archetypes: Carl Jung understood archetypes as universal, archaic patterns and images that derive from the collective unconscious. They are inherited potentials which are actualized when they enter consciousness as images or manifest in behavior on interaction with the outside world. Archetypes are patterns of behavior, that manifest for example in certain ways such as a “hero” type person or a “warrior” type person. These potential patterns of behavior are inherited patterns that manifest in different ways across world cultures but have patterns in common across cultures.

Complex: clusters of emotions that arise based on past experiences and associations, such as those resulting in a particular attitude toward one’s father or other father figures. Similar to a schema in modern day cognitive psychology. When these clusters of emotions are activated, they can be so strong that the person feels “possessed” by the strong emotions related to a theme. Jung though we should get to know our complexes and how they are activated, so under pressure these complexes don’t possess us.

Dream analysis: the act of analyzing our dream symbols and their meanings. Dream analysis can be done in different ways, and Jung had a particular view of how to do dream analysis. Jung’s view was that dreams were trying to communicate information to us. Jung believed that dreams could guide our future behavior, because of their profound relationship to the past, and their profound influence on our conscious mental life. Jung would talk with patients about their dreams and listen to multiple dreams, to help patients understand what the symbols were trying to teach. In general Jung believed the dreams were trying to teach us to be more whole, and to more fully understand parts of our personality.

Dreambody: the idea that body symptoms, as well as dreams, are trying to bring psychic information to our awareness. Dreams and body symptoms mirror or reflect similar information. By talking about the information in our body symptoms we will arrive at similar information to what we dreamed about.

Shadow: Jung described the shadow as desires and feelings that are not acceptable to society or the conscious psyche. People often try to hide their shadow or project it on to others. Jung thought people should try to get to know their shadow so it doesn’t destroy their lives or others. An example is “lust” or “greed” and that a person keeps having a lot of sexual lust or financial greed, but denies this. If they deny this too much, the energy of that lust or greed operates on its own in their psyche, and may make them have destructive or odd sexual boundaries or destructive odd financial behaviors. Denying the shadow also created repressed people that could not fully express themselves and had a tendency to blame others. Jung essentially wanted people to know all parts of themselves.

Individuation is the process by which a person actually becomes an “individual,” differentiated from all other people. Jung also described individuation as the process by which one becomes a “whole” person.

Synchronicity: Jung uses the term synchronicity to describe the “coincidence in time of two or more causally unrelated events which have the same or a similar meaning”

For References, please see the Reference section at the end of this Pressbooks book, where references are listed for Chapters 5 and 6.

This chapter is an edited and adapted version of an creative commons licensed book titled: Personality Theory in a Cultural Context by Mark Kelland (2015). The original authors bear no responsibility for the content of this edited and adapted chapter. The original book chapters can be found here: <http://cnx.org/content/col11901/1.1/ >

Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike