Annotating Your Way into Academic Discourse

What is Academic Discourse?

In the simplest terms, academic discourse is how scholars—or academics, as they are sometimes called—speak and write. Believe it or not, you already have some experience with academic discourse. Think back to the type of writing you completed in high school. You were probably expected to write in a more formal manner than if you were writing a text message or email to your friends. This formality is one aspect of academic discourse. Think, too, about your participation in class discussions. You probably spoke more formally and precisely during these discussions than if you were simply hanging out and talking with your friends. Academic discourse is not as casual as everyday speaking and writing, but strives to be more formal, complex, and precise. At the college level, you will be expected to further develop your abilities to participate in academic discourse. While each field or discipline (e.g. Biology, English, Psychology) has its own specific ways of writing, all disciplines within the academy encourage more sophisticated forms of communication than those we use every day.

In order to participate in the conversations that go on across disciplines within the academy, you will need to hone your abilities to use academic discourse effectively. This is a goal that should guide you early in your general education courses and all the way through the courses in your major. Inserting your voice into scholarly conversations—rather than just summarizing what other scholars have said—may be new for you. Some previous instructors may have told you not to include your “opinion” or “voice” in your writing. Maybe you have been prohibited from using “I.” This was the case for one of my students who described the difficulty this posed for him while writing a research paper: “I had to concentrate most of my efforts on analyzing my sources while trying to make sure my own voice was heard. I will admit that it was tough due to the fact that much of my high school writing career had been focused on keeping my voice out of [my] paper[s].” While it may take some time for you to become comfortable inserting your own voice into scholarly conversations, as a college-level reader and writer it is important that you become a visible and active part of your writing, just as you are expected to be an active reader. As noted in the introduction, annotation—which brings the acts of reading and writing together—can lay the foundation for your productive participation in scholarly conversations.

What is Annotation?

You have probably been asked by instructors to “mark-up” something you are reading. Maybe you were asked to jot down questions or notes in the margins, highlight the important parts, or circle words you don’t know. Maybe you have developed these habits on your own. The act of marking up a text is commonly referred to as annotating. The word “annotate” comes from the Latin word for “to note or mark” or “to note down.” To annotate is exactly that—it’s when you make notes on a text. “What does this have to do with entering scholarly conversations?” you may be wondering. How can marking up a reading help you respond to other scholars in your discipline?

When you annotate you are writing as you read. You make notes, you comment, react, and raise questions in the margins of your text. Reflections of your engagement with the text and its author, annotations represent the initial and preliminary ways you are participating in a scholarly conversation with the author of what you are reading. As such, your annotations can serve as the basis for the more extensive contributions you will be expected to make to scholarly conversations. For example, if you need to write an essay about something you have read, you can return to your annotations—to the questions you posed and comments you made in the margins—because these are moments in which you are already interacting with the text and its author. From there you can develop those preliminary interactions into a more detailed and comprehensive response.

Annotations can be handwritten on a printed text or applied digitally on an electronic text. As noted in the Introduction, annotating digitally will allow you to mark up any text, including those on the Web, access your annotations from any computer, and share your annotations with others. See the Introduction for specific instructions on how to digitally annotate the reading selections in this textbook.

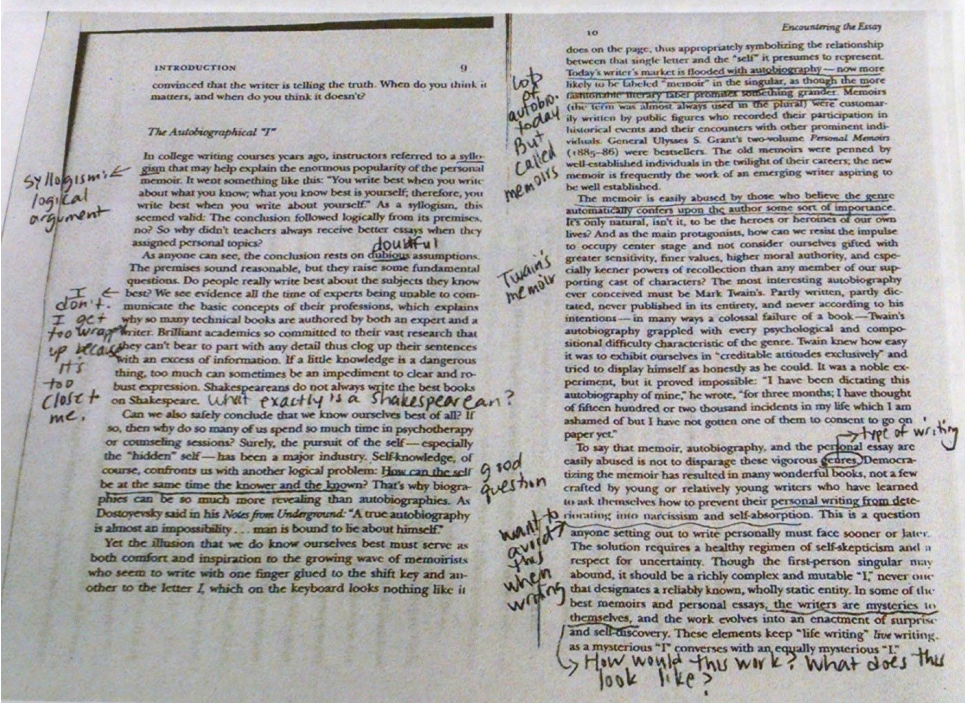

Instead of annotating the readings digitally, some instructors might ask you to print out the readings from this textbook and annotate them by hand as in the sample that follows

As you read the annotations in the sample text, notice the way the student uses annotations. The students ask questions, challenge points, define some words, and make personal connections. In this example, the students are engaging in more general annotation practices that are not governed by a specific reading strategy like those you will be introduced to in Chapter 2.

What Are the Differences Between Annotating and Highlighting?

It is important to keep in mind that annotating and highlighting often serve different purposes. Highlighting draws your attention to what you deem to be the important parts of a reading. Highlighting can help you recall those moments and the information presented in them. On the other hand, annotating encourages you to mark additional elements of the text—those beyond just “the important parts.” You will notice that in the previous samples highlighting is never used on its own. Rather, the yellow highlighting that does appear is accompanied by a comment, question, or some kind of written response. Although highlighting may be an important supplement to annotating, highlighting on its own is usually better preparation for assignments that ask you to memorize concepts and ideas from readings as opposed to those that ask you to write about and respond to what you have read. A record of your reading and your responses to the text and its author, annotations can provide you with the foundation for entering scholarly conversations, which is what you will be asked to do throughout college.