Leonard A. Jason; Olya Glantsman; Jack F. O'Brien; and Kaitlyn N. Ramian

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Understand the differences between prevention and treatment

- Differentiate interventions that bring about short term versus long term changes

- Appreciate the many layers of community interventions

- Identify critical elements of the Community Psychology approach

Most people think of psychologists in very traditional ways. For example, if you were to close your eyes and imagine a psychologist, there is a good chance you would think of a clinician or therapist. Clinical psychologists in their office settings often treat people with psychological problems one at a time by trying to change thought patterns, perceptions, or behavior. This is often called the “medical model” which involves a therapist delivering one-on-one psychotherapy to patients. There is a similar medical model in the field of medicine, and examples of this model would involve a physician fixing a patient’s broken arm or providing antibiotics for an infection. Although there is a clear need for this traditional model for those with medical or psychological problems, many do not have access to these services, and a very different approach will be required to successfully solve many of the individual and community problems that confront us.

Throughout this chapter you will learn about this different, strength-based approach, called Community Psychology, which emerged in different countries throughout the world (Reich et al., 2007). In the US, it began in the 1960s during a time when the nation was faced with protests, demonstrations, urban unrest, and intense struggles over issues such as the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights Movement. Many psychologists wanted to find ways to help solve these pressing societal issues, and some therapists were becoming increasingly disillusioned with their passive role in solely delivering the medical model, office-based psychotherapy (Cowen, 1973). At the 1965 Swampscott Conference in the US, the term “Community Psychology” was first used, and it signaled new roles and opportunities for psychologists by extending the reach of services to those who had been under-represented, focusing on prevention rather than just treatment of psychological problems, and by actively involving community members in the change process (Bennett et al., 1966). Over the past five decades, the field of Community Psychology has matured with recurring themes of prevention, social justice, and an ecological understanding of people within their environments. The goals of Community Psychology have been to examine and better understand complex individual–environment interactions in order to bring about social change, particularly for those who have limited resources and opportunities.

THE ROLE OF PREVENTION

One of the primary characteristics of the Community Psychology field is its focus on preventing rather than just treating social and psychological issues, and this can occur by boosting individual skills as well as by engaging in environmental change. The example in the box below provides an example of prevention directed toward saving lives at a beach, as drowning is one of the leading causes of death.

Imagine a beautiful lake with a long sandy beach surrounded by high cliffs. You notice a person who fell from one of the cliffs and who is now flailing about in the water. The lifeguard jumps in the water to save him. But then a bit later, another person wades too far into the water and panics as he does not know how to swim, and the lifeguard again dives into the water to save him. This pattern continues day after day, and the lifeguard recognizes that she cannot successfully rescue every person that falls into the water or wades in too deep. The lifeguard thinks that a solution would be to install railings to prevent people from falling from the cliffs and to teach the others on the beach how to swim. The lifeguard then attempts to persuade local officials of the need for railings and swimming lessons. During months of meetings with town officials, several powerful leaders are hesitant about spending the money to fund the needed changes. But the lifeguard is persistent and finally convinces them that scrambling to save someone only after they start to drown is dangerous, and the town officials budget the money to install railings on the cliffs and initiate swimming classes.

This example highlights a key prevention theme in the field of Community Psychology, and in this case, the preventive perspective involved getting to the root of the problem and then securing buy-in from the community in order to secure resources necessary to implement the changes. As illustrated in the textbox above, there are two radically different ways of bringing about change, which are referred to as first- and second-order change. First-order change attempts to eliminate deficits and problems by focusing exclusively on the individuals. When the lifeguard on the beach dove into the water to save one person after another, this was an example of a first-order intervention. There was no attention to identifying the real causes that contributed to people falling into the water and being at risk for drowning, and this band-aid approach would not provide the structural changes necessary to protect others on the beach or walking on the cliffs. A more effective approach involves second-order change, the strategy the lifeguard ultimately adopted, and this involved installing railings on the cliff and the teaching of swimming skills. Such changes get at the source of the problem and provide more enduring solutions for the entire community. A real example of this approach involved low-income Black preschool children who participated in a preventive learning preschool program (called the High/Scope Perry Preschool)—40 years later, participants in this program were found to have better high school completion, employment, income, and lower criminal behavior (Belfield et al., 2005).

There is a considerable appeal for a preventive approach, particularly as George Albee (1986) has shown that no condition or disease has ever been eliminated by focusing just on those with the problem. Prevention is also strongly endorsed by those in medicine who have been trained in the Public Health model, where services are provided to groups of people at risk for a disease or disorder in order to prevent them from developing it. Public Health practitioners seek to prevent medical problems in large groups of individuals through, for example, immunizations or finding and eliminating the environmental sources of disease outbreaks. Community Psychology has adopted this preventive Public Health approach in its efforts to analyze social problems, in addition to its unique characteristics, which you will read below and throughout this textbook.

An impressive example of prevention occurred with community efforts to change the landscape of tobacco use over the past 60 years. Today, attitudes have changed toward tobacco use, and community organizations aided by community psychologists made important contributions to this second-order change effort that involved reducing tobacco use. This began with the landmark Surgeon General’s Report in the 1960s, which summarized serious health problems caused by smoking. Advocacy groups such as Action on Smoking and Health helped to create non-smoking sections on planes and public transportation, and other organizations used strategies to promote nonsmokers’ rights in public buildings, restaurants, and work areas. Still, other work involved preventive school and community-based interventions as well as efforts to reduce youth access to tobacco, as shown in Case Study 1.1.

Case Study 1.1

Youth Tobacco Prevention

In the 1980s, school students informed community psychologist Leonard Jason that store merchants were openly selling them cigarettes. The students’ critical input was used to launch a study assessing illegal commercial sales of tobacco, and Jason’s team found that 80% of stores in the Chicago metropolitan area sold cigarettes to minors. When results of this study were publicized on the evening television news, Officer Bruce Talbot from the suburban town of Woodridge, Illinois contacted Jason to express interest in working on this community problem. Talbot and the Woodridge police with technical help from Jason’s team collected data showing that the majority of Woodridge merchants sold tobacco to minors. With these data, Woodridge passed legislation that fined both vendors caught illegally selling tobacco and minors found in possession of tobacco. Two years after implementing this program, rates of stores selling to minors decreased from an average of 70% to less than 5%. Woodridge was the first city in the US to demonstrate that cigarette smoking could be effectively decreased through legislation and enforcement. Jason later testified at the tobacco settlement hearings at the House Commerce Subcommittee on Health and Environment. In addition, because of Officer Talbot’s active participation in this Woodridge study, he had become known as a national authority on illegal sales of cigarettes to minors. Over time, Talbot advised communities throughout the country on how to establish effective laws to reduce youth access to tobacco. He also testified at congressional hearings in Washington D.C. in support of the Synar Amendment, which required states to reduce illegal sales of tobacco to minors using similar methods to those developed in Woodridge. Due to the enactment of the US federal government’s Synar Amendment, there has been a 21% nationwide decrease in the odds of tenth graders becoming daily smokers (Jason, 2013). However, legislative and regulatory efforts are now needed to stop access to fruity flavors that are luring teens to vaping.

This case study illustrates how preventive government policies can be fostered by community-based groups, with the support of community psychologists. Policies that emerge from concerned individuals, community activists, and coalitions are referred to as bottom-up approaches to second-order change. Community psychologists have clear roles to play in dialoguing and collaborating with community groups in these types of broad-based, preventive community change efforts.

A SOCIAL JUSTICE ORIENTATION

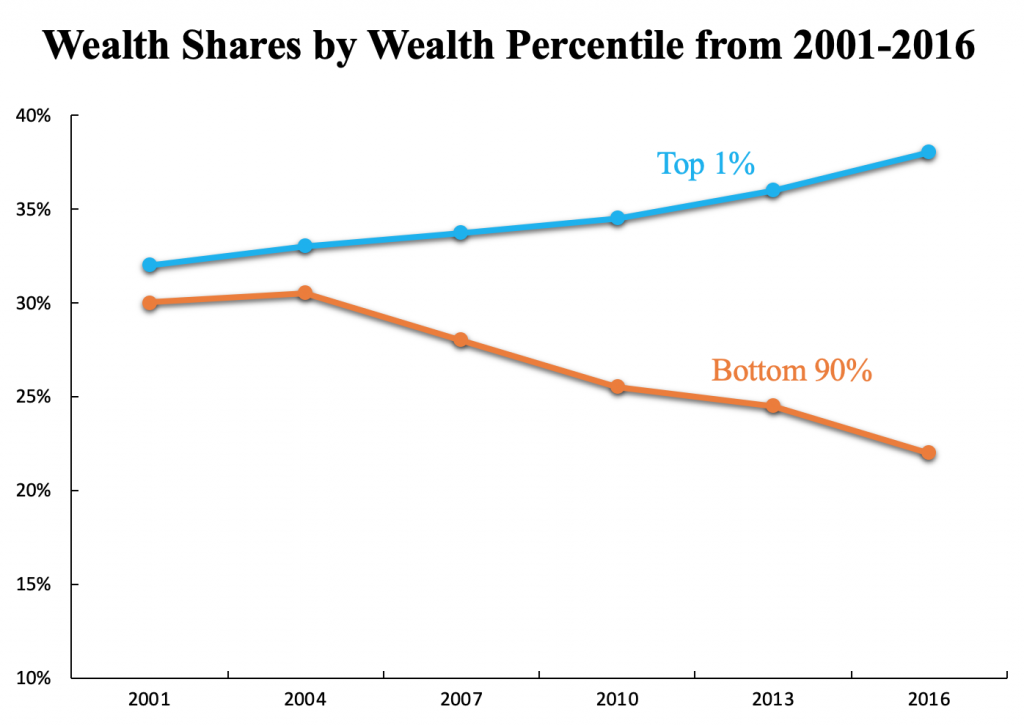

Community Psychology’s focus on social justice is due to the recognition that many of our social problems are perpetuated when resources are disproportionately allocated throughout our society (see Figure 1); this causes social and economic inequalities such as poverty, homelessness, underemployment and unemployment, and crime. Albee (1986) has concluded that societal factors such as unemployment, racism, sexism, and exploitation are the major causes of mental illness. In support of this, Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett’s (2009) book The Spirit Level documents how many health and social problems are caused by large inequalities throughout our societal structure. Economic inequalities not only cause stress and anxiety but also lead to more serious health problems. Studies of income inequality have shown how adult incomes have varied by race and gender, and this link allows you to make comparisons that provide animations for any combination of race, gender, income type, and household income level. Clearly, we need to look beyond the individual in exploring the basis of many of our social problems. Yet, most mental health professionals, including psychologists, have a tendency to try to solve mental health problems without attending to these environmental factors.

Community Psychology endorses a social justice and critical psychology perspective which looks at how oppressive social systems preserve classism, sexism, racism, homophobia, and other forms of discrimination and domination that perpetuate social injustice (Kagan et al., 2011). Clearly, there is a need to bring about a better society by dismantling unjust systems such as racism. This systemic US racism is evident in confederate monuments and flags displayed in prominent locations; high rates of discrimination in the healthcare system; redlining; police brutality (e.g., murder of George Floyd); and the disproportionate number of black, indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) in prisons.

In addition to identifying and combating systems that are unjust, community psychologists also challenge more subtle negative practices supported by psychological research and practice. Interventions developed for one group might not be appropriate and might even be harmful when applied to other groups. For example, a person with a social justice orientation would object to imposing intervention manuals, based on white norms, on students of color. Such materials would not be applicable or appropriate to the lived experiences of students of color (Bernal & Scharrón-del-Río, 2001).

The need for this social justice orientation is also evident when working with urban schools that are dealing with a lack of resources, overcrowded classrooms, community gang activity, and violence. Traditional mental health services such as therapy that deals with a student’s mental health issues would not address the income resource inequalities and stressful environmental factors that could be causing children’s mental health difficulties. Second-order change strategies, in contrast, would address the systems and structures causing the problems and might involve collaborative partnerships to bring more resources to the school as well as support community-based efforts to reduce gang activity and violence. As an example, Zimmerman and colleagues investigated what it takes to cultivate a safe environment where youth can grow up in a safe and healthy context (Heinze et al., 2018). These community psychologists found that improving physical features of neighborhoods such as fixing abandoned housing, cutting long grass, picking up trash, and planting a garden resulted in nearly 40% fewer assaults and violent crimes than street segments with vacant, abandoned lots.

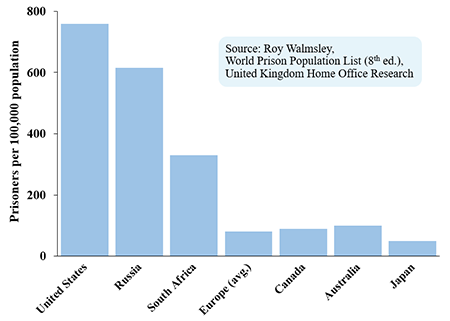

This social justice perspective can also be used to examine the institutionalization of millions of individuals in the US criminal justice system (see Figure 2). According to an individualistic perspective, people end up in prison because of factors such as mental illness, substance abuse, or a history of domestic violence. On the other hand, the Community Psychology social justice perspective posits that larger, structural forces (e.g., political, cultural, environmental, and institutional factors) need to be considered. A social justice perspective recognizes that millions of people have been locked up in US prisons due to more restrictive and punishing laws (such as mandatory minimum sentences and three-strikes that requires lifetime prison sentences), and there have also been changes in how we have dealt with patients in mental institutions. Through the 1960s and 1970s, many state-run mental hospitals were closed, which meant that discharged patients were supposed to be treated in our communities. However, funding to support these community-based treatment programs was significantly reduced in the 1980s, and as a consequence, many former patients of mental institutions became homeless or involved with the criminal justice system. Unfortunately, our prison system became the new settings where mentally ill people were warehoused. This is an example of first–order change, which has involved shifting mental patients from one inadequate institutional setting to another. Adopting a social justice perspective clearly broadens our understanding as to why millions of people in the US are incarcerated.

The tragedy of being forced to live in overcrowded and unsafe prisons is further compounded by the way 600,000 or more prison inmates are each year released back into communities in the US. Most prisons have at best meager rehabilitation programs, so most inmates have not been adequately prepared for transitioning back into our communities. Clearly, criminally justice-involved people transitioning back into our communities need more than weekly psychotherapy provided by traditional clinical psychologists.

Individuals who are released from jail uniformly state their greatest needs are for safe housing and employment but are rarely provided these critical resources. Given these circumstances, we should not be surprised that so many released inmates soon return to prison. A moving story by Scott about his heroin addiction and prison experiences is in Case Study 1.2.

Case Study 1.2

A Chance for Change through Oxford House

“I was born to an addicted mother who was a heroin addict and meth user as well. She left when I was 2 and I’ve only seen my mother one time when I was 17. I was adopted by my grandparents and was raised in a great family. I grew up having the best things in life and I was a standout sports player in high school until my life took a turn—for the worst. I dabbled with drugs and, after an injury that caused me to never play again, I turned to drugs. I became addicted to cocaine and meth and painkillers. Thinking I had it all under control, I caught my first felony and was sent to prison at 19. I became a prison gang member and later on was a gang leader of one of the most dangerous and second-largest gangs in the United States prison system. Once released after two years, I got out and didn’t know how to readjust to living normal. I started using Heroin and my life and addiction became the worst. Nineteen days later I was charged with an organized crime case and after bonding out, I went to treatment but never took it seriously. I was just addicted to the money and power I possessed and, no matter how much my family begged me to just stop, I went back to shooting dope… I was given a 7-year sentence and I served six and a half years at the deadly Ferguson unit here in Texas. Five years of that I spent in solitary confinement, locked down 23 hours a day due to my gang affiliations and actions in prison where I continued to use drugs and was just as much strung out as if I was still in the world. In 2013, I was paroled back home. I only lasted five months and was indicted on 2 first-degree felonies and offered 80 years. I went to jury trial where I was found not guilty but ended up with another indictment that I signed a five-year sentence for. I did four years, eight months, on that charge and was released back home in 2018. I lasted 2 days until I relapsed once again [on] heroin and on July 24, I did the last shot of heroin I’ll ever do. I overdosed and died in the ambulance only to be brought back and I woke up in Red River Detox, beat down and broken. I was there when I saw Philip and Cristen came to do a presentation. As I listened to Philip tell his story, I saw myself in him and realized that this is what I want. I wanted to finally make it and live a real life so I got into Oxford House where I’m sober today, working to have my family back in my life and holding my head up high each day because I can stand to look at the man in the mirror. I owe this to Oxford Chapter 14; they have saved my life and now I’m Re-Entry coordinator and have a chance to help people like me get a chance of making it. Thank you, Oxford House” (Oxford House Commemorative Program, 2018, p. 57).

This case study shows that the social justice needs of individuals coming out of prison include community-based programs that provide stable housing, new connections in terms of friends, and opportunities to earn money from legal sources. Oxford House, which is mentioned in this case study, is a community-based innovation for re-integrating people back into the community. The Oxford House network was started by people in recovery with just one house in 1975, and today it is the largest residential self-help organization that provides housing to over 20,000 people in cities and states throughout the US. The houses are always rented, and house members completely self-govern these homes without any help from professionals. Residents can live in these Oxford Houses indefinitely, as long as they remain abstinent, follow the house rules, and pay a weekly rent of about $100 to $120. Oxford Houses represent the types of promising social and community grassroots efforts that can offer people coming out of prisons and substance abuse treatment programs a chance to live in an environment where everyone is working, not using drugs, and behaving responsibly. Best part of all is that this program is self-supporting, as the residents rather than prison or drug abuse professionals are in charge of running each home. Here, the residents use their income from working to pay for all house expenses including rent and food (this video illustrates the Oxford House approach in a brief segment on the 60 Minutes TV broadcast). There are these types of innovative grassroots organizations throughout our communities, and community psychologists have key roles to play in helping to document the outcomes of these true incubators of social innovation, as illustrated on this link.

The prevention and social justice examples that we have provided above about installing railings at the cliff to prevent people from accidentally falling into the water or providing housing for those exiting from prison are examples of changing the environment or context. In fact, there is now considerable basic laboratory research that indicates that context or environment can have a shaping influence on the lives of humans and animals. For example, laboratory rats who are raised in “enriched” environments show brain weight increases of 7-10% (heavier and thicker cerebral cortexes) in comparison to those in “impoverished” environments (Diamond, 1988). There was a time when scientists did not believe that the brain could be changed by any environmental enrichment, but it is now commonly accepted that context can have a lasting and shaping influence on our behavior and even our brains. We need to attend to the environments of those living in poverty and exposed to high levels of crime, as these factors are associated with multiple negative outcomes including higher rates of chronic health conditions.

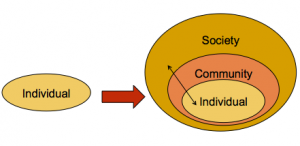

A SHIFT IN PERSPECTIVE: THE ECOLOGICAL MODEL

An aspect of Community Psychology that sets it apart from a more traditional Clinical Psychology is a shift beyond an individualistic perspective. Community psychologists consider how individuals, communities, and societies are interconnected, rather than focusing solely on the individual. As a result, the context or environment is considered an integral part when trying to understand and work with communities and individuals embedded in them.

This shift in thinking is referred to as an ecological perspective. Ecological means that there are multiple levels or layers of issues that need to be considered, including the individual, family, neighborhood, community, and policies at the national level. For example, let’s continue our examination of the criminal justice system with another case example. A person, who we shall call Jane, had been involved in an auto accident causing severe pain, and subsequently became addicted to painkillers. When it became more difficult to purchase these medications, she began using heroin to reduce the pain, became involved in buying and selling illegal substances, became estranged from her family, and was caught and sentenced to prison. At the individual level, Jane is certainly distressed and addicted to painkillers, and this has now disrupted relationships with her family and friends. But an ecological perspective would point to a number of factors beyond the individual and group level contributing to this unfortunate situation. Healthcare organizations contributed to this problem, as many physicians were all too willing to profit by overprescribing pain medications to their patients. The pharmaceutical industry was part of the problem as it reaped huge profits by oversupplying these drugs to pharmacies. At the community level, the criminal justice system also shares blame for delivering punishment in crowded, unsafe prisons for individuals clearly in need of substance use treatment. Finally, at a societal level, federal regulators allowed opiate drugs like OxyContin to be sold for long-term rather than just short-term use, and legislators inappropriately passed laws extending sentences for those who are in prison due to offenses caused by substance use disorders. These types of difficult and complex social problems are produced and maintained by multiple ecological influences, and corrective second–order community solutions will have to deal with these contextual issues.

In addition to thinking about these multiple ecological levels, the community psychologist James Kelly (2006) has proposed several useful principles that help us better understand how social environments affect people. For example, the ecological principle of interdependence indicates that everything is connected, so changing one aspect of a setting or environment will have many ripple effects. For example, if you provide those released from prison a safe place to live with others who are gainfully employed (as occurs in Oxford Houses), this setting can then lead to positive behavior changes. Living among others in recovery provides a gentle but powerful influence for spending more time in work settings in order to pay for rent and less time in environments with high levels of illegal activities. The ecological principle of adaptation indicates that behavior adaptive in one setting may not be adaptive in other settings. A person who was highly skilled at selling drugs and stealing will find that these behaviors are not adaptive or successful in a sober living house, so the person will have to learn new interpersonal skills that are adaptive in this recovery setting. The ecological perspective broadens the focus beyond individuals to include their context or environment, by requiring us to think about how organizations, neighborhoods, communities, and societies are structured as systems.

This ecological perspective helps us move beyond an individualistic orientation for understanding many of our significant social problems such as homelessness, which in the US affects over a half a million people (National Alliance to End Homelessness, 2018). At the individual level, many of these individuals do suffer from substance abuse and mental health problems, and they often cycle in and out of the criminal justice system. However, the ecological perspective would focus attention on the lack of affordable housing for low-income people, and thus call for higher-order interventions that go beyond the individual. As an example, Housing First is an innovative intervention founded by clinical-community psychologist Sam Tsemberis, which provides the homeless a home first and then treatment services. This Community Psychology intervention is based on the belief that by providing housing first, there will be many positive ripple effects that lead to beneficial changes in the formerly homeless person’s behaviors and functioning. In this video link, Sam talks about the founding of the Housing First innovation, which is a model now used throughout the US.

Case Study 1.3 below is the story of Russell, who used the Housing First program to find a home and successfully integrate back into the community.

Case Study 1.3

Pathways to Housing: Russell’s Story

“Russell grew up in Southeast DC before becoming homeless more than three decades ago. Struggling with schizophrenia, Russell was in and out of jail and the hospital. He spent the last ten years sleeping on a park bench downtown. This fall, with the help of his Pathways team, Russell moved off the streets and into a permanent apartment. For the first time since 1980, Russell finally has a roof over his head and a place to call home. His favorite thing about the new space? “The television.” A die-hard Washington Redskins fan, Russell is thrilled to be able to cheer his team on—hopefully all the way to the Super Bowl—from the comfort of his living room. For Russell though, it is more than just watching his favorite team play. After just two months, Russell is beginning to thrive in his new home. He has accomplished a number of personal goals including saving to buy a new bike.” (Pathways to Housing: Russell’s Story).

The ecological perspective provides an opportunity to examine the issues associated with homelessness beyond the individual level of analysis. Through this framework, we can understand homelessness within complicated personal, organizational, and community systems. In the case of Russell described in the above case study, at the individual level he was dealing with chronic stress, poor health, and mental illness, and felt hopeless. But his sense of despair was in part due to a group level factor, which was the lack of available support from friends or family members. Providing him temporary shelter at night and access to food kitchens represents first-order, individualistic solutions that had never been successful. The Housing First innovation was at a higher environmental level, and once placed in this permanent supportive setting, it had ripple effects on Russell’s sense of hope, connection with others, and ultimately his improved quality of life. Outcome studies have indicated that Housing First is successful in helping vulnerable individuals gain the resources to overcome homelessness, and this program was included in the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs.

The ecological perspective can also be applied to public health crises, such as the ongoing COVID-19 epidemic. Practical Application 1.1 shows how ecological levels of analysis can be used to address those most affected by the crisis.

Practical Application 1.1

Application of the Ecological Perspective to the COVID-19 Crisis

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a worldwide health epidemic, which spreads easily and has a high mortality rate. The disease disproportionately affects many under-resourced populations who are already at-risk of contracting illnesses due to social inequalities such as unstable housing, lack of access to affordable food, and inadequate access to health care. Due to the economic social injustices, many under-resourced people have no choice but to work in essential jobs or remain unemployed. These factors have had devastating consequences on people of color, who have the highest rates of COVID-19 mortality.

Community Psychology’s focus on ecological levels of analyses can offer some solutions to the systemic problems that increase risk of exposure to COVID-19 among under-resourced groups. For example, people experiencing homelessness or living in shelters are exposed to many diseases such as COVID-19. Chances of contracting COVID-19 could be reduced if these individuals had access to safe and stable housing, such as that provided by the Housing First or the Oxford House models. For example, Oxford House recovery homes have set up a room in their homes for COVID-19 positive residents to isolate themselves for 14 days. This allows the spread of the illness to be significantly reduced while still offering the residents safe and stable housing. This ecological approach goes beyond the individual by providing recovery home environments conducive for reducing risk of COVID-19.

One example of an individual level prevention strategy is choosing to get vaccinated, which is important to reduce the risk of exposure and transmission of COVID-19. What strategies might make you more successful in convincing others to get vaccinated? But don’t stop there! Speaking to friends and family members is a crucial first step, but can you think of even more impactful ecological interventions. Going back to the risk factors discussed earlier affecting under-resourced groups, how can we similarly apply an ecological perspective that helps individuals subjected to these environmental risk factors?

For COVID-19 informational resources, go to https://www.scra27.org/resources/covid-19/ and https://www.apa.org/pubs/highlights/covid-19-articles#most-recent.

This ecological perspective can also be applied to more preventive interventions, such as stopping the recruitment of youth into gangs. This occurred by providing youth anti-gang classroom sessions as well as after-school activities (e.g., organized sports clinics that encouraged intragroup cooperation, opportunities to travel out of their neighborhood to participate in events and activities, etc.) (Thompson & Jason, 1988). There are many examples of how a multi-scale, ecological systems model of people-environment transactions can broaden our understanding of societal problems (Stokols, 2018).

OTHER KEY PRINCIPLES OF COMMUNITY PSYCHOLOGY

There are other key features of the field of Community Psychology, as will be described in the subsequent chapters, and below we briefly review them.

Respect for Diversity

Community Psychology has respect for diversity and appreciates the views and norms of groups from different ethnic or racial backgrounds, as well as those of different genders, sexual orientations, and levels of abilities or disabilities. Community psychologists work to counter oppression such as racism (white persons have access to resources and opportunities not available to ethnic minorities), sexism (discrimination directed at women), heterosexism (discrimination toward non-heterosexual individuals), and ableism (discrimination toward those with physical or mental disabilities). The task of creating a more equitable society should not fall on the shoulders of those who have directly experienced its inequalities, including ethnic minorities, those with disabilities, and other underprivileged populations. Being sensitive to issues of diversity is critical in designing interventions, and if preventive interventions are culturally-tailored to meet the diverse needs of the recipients, they are more likely to be appreciated, valued, and maintained over time.

Active Citizen Participation

The Brazilian educator Freire (1970) wrote that change efforts begin by helping people identify the issues they have strong feelings about, and that community members should be part of the search for solutions through active citizen participation. Involving community groups and community members in an egalitarian partnership and collaboration is one means of enabling people to re-establish power and control over the obstacles or barriers they confront. When our community partners are recognized as experts, they are able to advocate for themselves as well as for others, as indicated in Case Study 1.1 that described how Officer Talbot became an activist for reducing youth access to tobacco. Individuals build valuable skills when they help define issues, provide solutions, and have a voice in decisions that ultimately affect them and their community. This Community Psychology approach shifts the power dynamic so that all parties collaborate by participating in the decision-making. Community members are seen as resources who provide unique points of view about the community and the institutional barriers that might need to be overcome in social justice interventions. All partners are involved equally in the research process in what is called community-based participatory research.

Grounding in Research and Evaluation

In striving to understand the relationship between social systems and individual well-being, community psychologists base advocacy and social change on data that are generated from research and apply a number of evaluation tools to conceptualize and understand these complex ecological issues. Community psychologists believe that it is important to evaluate whether their policy and social change preventive interventions have been successful in meeting their objectives, and the voice of the community should be brought into these evaluation efforts. They conduct community-based action-oriented research and often employ multiple methods including what are called qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods research (Jason & Glenwick, 2016). No one method is superior to another, and what is needed is a match between the research methods and the nature of the questions asked by the community members and researchers. Community psychologists, like Durlak and Pachan (2012), have used adventuresome research methods to investigate the effects of hundreds of programs dedicated to preventing mental health problems in children and adolescents, and the findings showed positive outcomes in terms of improved competence, adjustment, and reduced problems.

Interdisciplinary Collaboration

Social issues are complex and intertwined throughout every fiber of our society, as pointed out by the ecological perspective. When working with individuals who have been marginalized and oppressed, it is important to recognize that issues such as addiction and homelessness require expertise from many perspectives. Community Psychology promotes interdisciplinary collaboration with professionals from a diverse array of fields. For example, a community psychologist helped put together the multidisciplinary team evaluating Oxford House efforts to help re-integrate individuals with substance use problems back into the community. One member of the team was a sociologist who studies social networks, and one of the important findings was that the best predictor of positive long-term outcomes was having at least one friend in the recovery houses. Also, part of this team was an economist who found that the economic benefits were greater, and costs were less for this Oxford House community intervention than an intervention delivered by professionals. Other important contributions were made by a social worker, a Public Health researcher, Oxford House members, and undergraduate and graduate students who each contributed unique skills and valuable perspectives to the research team. You can see how these types of collaborations can emerge by using the idea tree exercise, which different disciplines can work together to create new ideas and advance knowledge across fields.

Sense of Community

One of the core values of Community Psychology is the key role of psychological sense of community, which describes our need for a supportive network of people on which we can depend. Promoting a healthy sense of community is one of the overarching goals of Community Psychology, as a loss of connectedness lies at the root of many of our social problems. So understanding how to promote a sense of belonging, interdependence, and mutual commitment is integral to achieving second-order change. If people feel that they exist within a larger interdependent network, they are more willing to commit to and even make personal sacrifices for that group to bring about long-term social changes. From a Community Psychology perspective, an intervention would be considered unsuccessful if it increased students’ achievement test scores but fostered competition and rivalry that damaged their sense of community.

Empowerment

Another important feature of Community Psychology is empowerment, defined as the process by which people and communities who have historically not had control over their lives become masters of their own fate. People and communities who are empowered have greater autonomy and self-determination, gain more access to resources, participate in community decision-making, and begin to work toward changing oppressive community and societal conditions. As shown in Case Study 1.3, individuals such as Russell who have been homeless often feel a lack of control over their lives. However, once provided stable housing and connections with others, they feel more empowered and able to gain the needed resources to improve the quality of their lives.

Policy

Community psychologists also enter the policy arena by trying to influence laws and regulations, as illustrated by the work on reducing minors’ access to tobacco described in Case Study 1.1. Community psychologists have made valuable contributions at local, state, national, and international levels by collaborating with community-based organizations and serving as senior policy advisors. It is through policy work that over the last century, the length of the human lifespan has doubled, poverty has dropped by over 50%, and child and infant mortality rates have been reduced by 90%.

Over the next decades, there is a need for policy-level interventions to help overcome dilemmas such as escalating population growth (as this will create more demands on our planet’s limited drinking water, energy, and food resources), growing inequalities between the highest and lowest compensated workers (which will increasingly lead to societal strains and discontent as automation and artificial intelligence will eliminate many jobs), increasing temperatures due to the burning of fossil fuels (which will result in higher sea levels and more destructive hurricanes), and the expanding needs of our growing elderly population. The principles of Community Psychology that have been successfully used to change policy at the local and community level might also be employed to deal with these more global issues that are impacting us now, and will increasingly do so in the future. This video link shows what is possible when we reflect upon policy.

Promoting Wellness

Finally, the promotion of wellness is another feature of Community Psychology. Wellness is not simply the stereotypical lack of illness, but rather the combination of physical, psychological, and social health, including attainment of personal goals and well-being. Furthermore, Community Psychology applies this concept to also include groups of people, and communities—in a sense, collective wellness.

SUMMING UP

This chapter has reviewed the key features of the Community Psychology field, including its emphasis on prevention, its social justice orientation, and its shift to a more ecological perspective. The case studies presented in this chapter illustrate ways in which community psychologists have engaged in systemic and structural changes toward social justice. Many of the examples in this textbook are from the US, although you will read about important international change agents and community psychologists such as Maritza Montero of Venezuela, Nelson Mandela of South Africa, Mahatma Gandhi of India, and Paulo Freire of Brazil.

Students who read these chapters will learn how we can mount community-based research and practices that emphasize fair and equitable allocation of resources and opportunities. This social justice perspective of Community Psychology recognizes inequalities that often exist in our societies. Clearly, there are countries where challenging authorities, as recommended in this textbook, could result in persecution and imprisonment. But we hope that the tools offered in this textbook can be adapted in useful ways in these oppressive settings. For communities that have been historically marginalized, our field works toward providing greater access to resources and decision making in the hopes of making enduring, systems-level change.

REFERENCES

Albee, G. (1986). Toward a just society. Lessons from observations on the primary prevention of psychopathology. The American Psychologist, 41(8), 891-898. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066X.41.8.891

Bernal G., & Scharrón-del-Río, M. R. (2001). Are empirically supported treatments valid for ethnic minorities? Toward an alternative approach for treatment research. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 7, 328-342. https://doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.7.4.328

Belfield, C., Barnett, W., & Schweinhart, L. (2005). Lifetime effects: The High/Scope Perry Preschool study through age 40 (Monographs of the High/Scope Educational Research Foundation, no. 14). High/Scope Press.

Bennett, C. C., Anderson, L. S., Cooper, S., Hassol, L., Klein, D. C., & Rosenblum, G. (1966). Community Psychology: A report of the Boston Conference on the Education of Psychologists for Community Mental Health. Boston University Press.

Card, D., & Krueger, A. B. (1994). Minimum wages and employment: A case study of the fast-food industry in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. The American Economic Review, 84(4), 772-793. http://davidcard.berkeley.edu/papers/njmin-aer.pdf

Cowen, E. (1973). Social and community interventions. Annual Review of Psychology, 24(1), 423–472.

Diamond, M. C. (1988). Enriching heredity: The impact of the environment on the anatomy of the brain. Free Press.

Dobbie, W., & R. G. Fryer, Jr. (2013, Oct). The medium term impacts of high achieving Charter Schools on non-test score outcomes. NBER Working Paper 19581. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w19581

Durlak, J. A., & Pachan, M. (2012). Meta-analysis in community-oriented research. In. L. A. Jason & D. S. Glenwick (Eds.), Methodological approaches to community-based research. (pp. 111-122). American Psychological Association.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Herder and Herder.

Heinze, J. E., Krusky-Morey, A., Vagi, K. J., Reischl, T. M., Franzen, S., Pruett, N. K., Cunningham, R.M., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2018). Busy streets theory: The effects of community-engaged greening on violence. American Journal of Community Psychology, 62(1-2), 101-109. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12270

Jason, L. A. (2013). Principles of social change. (pp. 17-21). Oxford University Press.

Jason, L. A., & Glenwick, D. S. (Eds.). (2016). Handbook of methodological approaches to community-based research: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods. Oxford University Press.

Kagan, C., Burton, M., Duckett, P., Lawthom, R., & Siddiquee, A. (Eds.). (2011). Critical Community Psychology (1st ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

Kelly, J. G. (2006). Becoming ecological: An expedition into Community Psychology. Oxford University Press.

Oxford House, Inc. (2018). Oxford House Recovery Stories. 2018 Annual Oxford House World Convention. Kansas City, Missouri.

Pathways to Housing: Russell’s story. https://www.pathwaystohousingdc.org/stories/russell

Pinker, S. (2011). The better angels of our nature: Why violence has declined. Viking.

Reich, S., Riemer, M., Prilleltensky, I., & Montero, M. (Eds.). (2007). International Community Psychology. History and theories. Springer.

Stokols, D. (2018). Social ecology in the digital age: Solving complex problems in a globalized world. Academic Press. https://www.elsevier.com/books/social-ecology-in-the-digital-age/stokols/978-0-12-803113-1

State of homelessness. National Alliance to End Homelessness. https://endhomelessness.org/homelessness-in-america/homelessness-statistics/state-of-homelessness-report/

Thompson, D. W., & Jason, L. A. (1988). Street gangs and preventive interventions. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 15, 323-333.

Wilkinson, R., & Pickett, K. (2009). The spirit level: Why more equal societies almost always do better. Allen Lane.

Interests into Action with SCRA!

SCRA has several interest groups that provide networking opportunities and diverse ways to pursue interests that matter to you. Find out more at here!

Acknowledgments: We wish to thank Bridget Harris and Laura Sklansky for their superb help in editing this chapter, as well as Mark Zinn for his expert assistance with helping us overcome a wide range of internet and computer problems.