4.8 Helping and Prosocial Behavior

Bill Pelz and Herkimer County Community College and Pelz

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the bystander effect

- Describe altruism

THE BYSTANDER EFFECT

The problem of witnesses not intervening to help a victim is a common occurrence. Social psychologists began trying to answer this question following the unfortunate murder of 19-year-old Kitty Genovese in 1964 (Dovidio, Piliavin, Schroeder, & Penner, 2006; Penner, Dovidio, Piliavin, & Schroeder, 2005). A knife-wielding assailant attacked Kitty repeatedly as she was returning to her apartment in Queens, New York early one morning. This story became famous because reportedly at least 38 residents in the apartment building heard her cries for help and did nothing—neither helping her nor summoning the police—though these have facts been disputed. More recently, in 2010, Hugo Alfredo Tale-Yax was stabbed when he apparently tried to intervene in an argument between a man and woman. As he lay dying in the street, only one man checked his status, but many others simply glanced at the scene and continued on their way. (One passerby did stop to take a cellphone photo, however.) Unfortunately, failures to come to the aid of someone in need are not unique, as the segments on “What Would You Do?” show. Help is not always forthcoming for those who may need it the most. Trying to understand why people do not always help became the focus of bystander intervention research (e.g., Latané & Darley, 1970).

When Do People Help?

The bystander effect is a phenomenon in which a witness or bystander does not volunteer to help a victim or person in distress. Instead, they just watch what is happening. Social psychologists hold that we make these decisions based on the social situation, not our own personality variables. Why do you think the bystanders didn’t help Genovese? What are the benefits to helping her? What are the risks? It is very likely you listed more costs than benefits to helping. In this situation, bystanders likely feared for their own lives—if they went to her aid the attacker might harm them. However, how difficult would it have been to make a phone call to the police from the safety of their apartments? Why do you think no one helped in any way? Social psychologists claim that diffusion of responsibility is the likely explanation. Diffusion of responsibility is the tendency for no one in a group to help because the responsibility to help is spread throughout the group (Bandura, 1999). Because there were many witnesses to the attack on Genovese, as evidenced by the number of lit apartment windows in the building, individuals assumed someone else must have already called the police. The responsibility to call the police was diffused across the number of witnesses to the crime. Have you ever passed an accident on the freeway and assumed that a victim or certainly another motorist has already reported the accident? In general, the greater the number of bystanders, the less likely any one person will help.

To answer the question regarding when people help, researchers have focused on

- how bystanders come to define emergencies,

- when they decide to take responsibility for helping, and

- how the costs and benefits of intervening affect their decisions of whether to help.

Defining the situation: The role of pluralistic ignorance

The decision to help is not a simple yes/no proposition. In fact, a series of questions must be addressed before help is given—even in emergencies in which time may be of the essence. Sometimes help comes quickly; an onlooker recently jumped from a Philadelphia subway platform to help a stranger who had fallen on the track. Help was clearly needed and was quickly given. But some situations are ambiguous, and potential helpers may have to decide whether a situation is one in which help, in fact, needs to be given.

To define ambiguous situations (including many emergencies), potential helpers may look to the action of others to decide what should be done. But those others are looking around too, also trying to figure out what to do. Everyone is looking, but no one is acting! Relying on others to define the situation and to then erroneously conclude that no intervention is necessary when help is actually needed is called pluralistic ignorance (Latané & Darley, 1970). When people use the inactions of others to define their own course of action, the resulting pluralistic ignorance leads to less help being given.

Do I have to be the one to help?: Diffusion of responsibility

Simply being with others may facilitate or inhibit whether we get involved in other ways as well. In situations in which help is needed, the presence or absence of others may affect whether a bystander will assume personal responsibility to give the assistance. If the bystander is alone, personal responsibility to help falls solely on the shoulders of that person. But what if others are present? Although it might seem that having more potential helpers around would increase the chances of the victim getting help, the opposite is often the case. Knowing that someone else could help seems to relieve bystanders of personal responsibility, so bystanders do not intervene. This phenomenon is known as diffusion of responsibility (Darley & Latané, 1968).

On the other hand, watch the video of the race officials following the 2013 Boston Marathon after two bombs exploded as runners crossed the finish line. Despite the presence of many spectators, the yellow-jacketed race officials immediately rushed to give aid and comfort to the victims of the blast. Each one no doubt felt a personal responsibility to help by virtue of their official capacity in the event; fulfilling the obligations of their roles overrode the influence of the diffusion of responsibility effect.

There is an extensive body of research showing the negative impact of pluralistic ignorance and diffusion of responsibility on helping (Fisher et al., 2011), in both emergencies and everyday need situations. These studies show the tremendous importance potential helpers place on the social situation in which unfortunate events occur, especially when it is not clear what should be done and who should do it. Other people provide important social information about how we should act and what our personal obligations might be. But does knowing a person needs help and accepting responsibility to provide that help mean the person will get assistance? Not necessarily.

The costs and rewards of helping

The nature of the help needed plays a crucial role in determining what happens next. Specifically, potential helpers engage in a cost–benefit analysis before getting involved (Dovidio et al., 2006). If the needed help is of relatively low cost in terms of time, money, resources, or risk, then help is more likely to be given. Lending a classmate a pencil is easy; confronting the knife-wielding assailant who attacked Kitty Genovese is an entirely different matter. As the unfortunate case of Hugo Alfredo Tale-Yax demonstrates, intervening may cost the life of the helper.

The potential rewards of helping someone will also enter into the equation, perhaps offsetting the cost of helping. Thanks from the recipient of help may be a sufficient reward. If helpful acts are recognized by others, helpers may receive social rewards of praise or monetary rewards. Even avoiding feelings of guilt if one does not help may be considered a benefit. Potential helpers consider how much helping will cost and compare those costs to the rewards that might be realized; it is the economics of helping. If costs outweigh the rewards, helping is less likely. If rewards are greater than cost, helping is more likely.

PROSOCIAL BEHAVIOR AND ALTRUISM

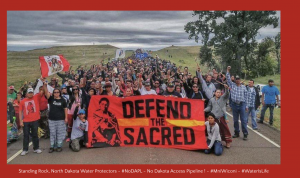

Do you voluntarily help others? Voluntary behavior with the intent to help other people is called prosocial behavior. Why do people help other people? Is personal benefit such as feeling good about oneself the only reason people help one another? Research suggests there are many other reasons. Altruism is people’s desire to help others even if the costs outweigh the benefits of helping. In fact, people acting in altruistic ways may disregard the personal costs associated with helping. For example, in 2016, news accounts reported that of the thousands of people who traveled to the Standing Rock Sioux reservation in North Dakota to help protest the construction of the Dakota Access pipeline, hundreds were arrested and/or injured in their standoff with police. One young woman received considerable media attention for the injuries she suffered, almost losing her arm from a rubber bullet (Wong, 2016).

Some researchers suggest that altruism operates on empathy. Empathy is the capacity to understand another person’s perspective, to feel what he or she feels. An empathetic person makes an emotional connection with others and feels compelled to help (Batson, 1991). Other researchers argue that altruism is a form of selfless helping that is not motivated by benefits or feeling good about oneself. Certainly, after helping, people feel good about themselves, but some researchers argue that this is a consequence of altruism, not a cause. Other researchers argue that helping is always self-serving because our egos are involved, and we receive benefits from helping (Cialdini, Brown, Lewis, Luce, & Neuberg 1997). It is challenging to determine experimentally the true motivation for helping, whether is it largely self-serving (egoism) or selfless (altruism). Thus, a debate on whether pure altruism exists continues.

Link to Learning

See this excerpt from the popular TV series Friends episode for a discussion of the egoism versus altruism debate.

Who Helps?

Do you know someone who always seems to be ready, willing, and able to help? Do you know someone who never helps out? It seems there are personality and individual differences in the helpfulness of others. To answer the question of who chooses to help, researchers have examined 1) the role that sex and gender play in helping, 2) what personality traits are associated with helping, and 3) the characteristics of the “prosocial personality.”

Who are more helpful—men or women?

In terms of individual differences that might matter, one obvious question is whether men or women are more likely to help. In one of the “What Would You Do?” segments, a man takes a woman’s purse from the back of her chair and then leaves the restaurant. Initially, no one responds, but as soon as the woman asks about her missing purse, a group of men immediately rush out the door to catch the thief. So, are men more helpful than women? The quick answer is “not necessarily.” It all depends on the type of help needed. To be very clear, the general level of helpfulness may be pretty much equivalent between the sexes, but men and women help in different ways (Becker & Eagly, 2004; Eagly & Crowley, 1986). What accounts for these differences?

Two factors help to explain sex and gender differences in helping. The first is related to the cost–benefit analysis process discussed previously. Physical differences between men and women may come into play (e.g., Wood & Eagly, 2002); the fact that men tend to have greater upper body strength than women makes the cost of intervening in some situations less for a man. Confronting a thief is a risky proposition, and some strength may be needed in case the perpetrator decides to fight. A bigger, stronger bystander is less likely to be injured and more likely to be successful.

The second explanation is simple socialization. Men and women have traditionally been raised to play different social roles that prepare them to respond differently to the needs of others, and people tend to help in ways that are most consistent with their gender roles. Female gender roles encourage women to be compassionate, caring, and nurturing; male gender roles encourage men to take physical risks, to be heroic and chivalrous, and to be protective of those less powerful. As a consequence of social training and the gender roles that people have assumed, men may be more likely to jump onto subway tracks to save a fallen passenger, but women are more likely to give comfort to a friend with personal problems (Diekman & Eagly, 2000; Eagly & Crowley, 1986). There may be some specialization in the types of help given by the two sexes, but it is nice to know that there is someone out there—man or woman—who is able to give you the help that you need, regardless of what kind of help it might be.

A trait for being helpful: Agreeableness

Graziano and his colleagues (e.g., Graziano & Tobin, 2009; Graziano, Habishi, Sheese, & Tobin, 2007) have explored how agreeableness—one of the Big Five personality dimensions (e.g., Costa & McCrae, 1988)—plays an important role in prosocial behavior. Agreeableness is a core trait that includes such dispositional characteristics as being sympathetic, generous, forgiving, and helpful, and behavioral tendencies toward harmonious social relations and likability. At the conceptual level, a positive relationship between agreeableness and helping may be expected, and research by Graziano et al. (2007) has found that those higher on the agreeableness dimension are, in fact, more likely than those low on agreeableness to help siblings, friends, strangers, or members of some other group. Agreeable people seem to expect that others will be similarly cooperative and generous in interpersonal relations, and they, therefore, act in helpful ways that are likely to elicit positive social interactions.

Searching for the prosocial personality

Rather than focusing on a single trait, Penner and his colleagues (Penner, Fritzsche, Craiger, & Freifeld, 1995; Penner & Orom, 2010) have taken a somewhat broader perspective and identified what they call the prosocial personality orientation. Their research indicates that two major characteristics are related to the prosocial personality and prosocial behavior. The first characteristic is called other-oriented empathy: People high on this dimension have a strong sense of social responsibility, empathize with and feel emotionally tied to those in need, understand the problems the victim is experiencing, and have a heightened sense of moral obligation to be helpful. This factor has been shown to be highly correlated with the trait of agreeableness discussed previously. The second characteristic, helpfulness, is more behaviorally oriented. Those high on the helpfulness factor have been helpful in the past, and because they believe they can be effective with the help they give, they are more likely to be helpful in the future.

Why Help?

Finally, the question of why a person would help needs to be asked. What motivation is there for that behavior? Psychologists have suggested that 1) evolutionary forces may serve to predispose humans to help others, 2) egoistic concerns may determine if and when help will be given, and 3) selfless, altruistic motives may also promote helping in some cases.

Evolutionary roots for prosocial behavior

Our evolutionary past may provide keys about why we help (Buss, 2004). Our very survival was no doubt promoted by the prosocial relations with clan and family members, and, as a hereditary consequence, we may now be especially likely to help those closest to us—blood-related relatives with whom we share a genetic heritage. According to evolutionary psychology, we are helpful in ways that increase the chances that our DNA will be passed along to future generations (Burnstein, Crandall, & Kitayama, 1994)—the goal of the “selfish gene” (Dawkins, 1976). Our personal DNA may not always move on, but we can still be successful in getting some portion of our DNA transmitted if our daughters, sons, nephews, nieces, and cousins survive to produce offspring. The favoritism shown for helping our blood relatives is called kin selection (Hamilton, 1964).

But, we do not restrict our relationships just to our own family members. We live in groups that include individuals who are unrelated to us, and we often help them too. Why? Reciprocal altruism(Trivers, 1971) provides the answer. Because of reciprocal altruism, we are all better off in the long run if we help one another. If helping someone now increases the chances that you will be helped later, then your overall chances of survival are increased. There is the chance that someone will take advantage of your help and not return your favors. But people seem predisposed to identify those who fail to reciprocate, and punishments including social exclusion may result (Buss, 2004). Cheaters will not enjoy the benefit of help from others, reducing the likelihood of the survival of themselves and their kin.

Evolutionary forces may provide a general inclination for being helpful, but they may not be as good an explanation for why we help in the here and now. What factors serve as proximal influences for decisions to help?

Egoistic motivation for helping

Most people would like to think that they help others because they are concerned about the other person’s plight. In truth, the reasons why we help may be more about ourselves than others: Egoistic or selfish motivations may make us help. Implicitly, we may ask, “What’s in it for me?” There are two major theories that explain what types of reinforcement helpers may be seeking. The negative state relief model (e.g., Cialdini, Darby, & Vincent, 1973; Cialdini, Kenrick, & Baumann, 1982) suggests that people sometimes help in order to make themselves feel better. Whenever we are feeling sad, we can use helping someone else as a positive mood boost to feel happier. Through socialization, we have learned that helping can serve as a secondary reinforcement that will relieve negative moods (Cialdini & Kenrick, 1976).

The arousal: cost–reward model provides an additional way to understand why people help (e.g., Piliavin, Dovidio, Gaertner, & Clark, 1981). This model focuses on the aversive feelings aroused by seeing another in need. If you have ever heard an injured puppy yelping in pain, you know that feeling, and you know that the best way to relieve that feeling is to help and to comfort the puppy. Similarly, when we see someone who is suffering in some way (e.g., injured, homeless, hungry), we vicariously experience a sympathetic arousal that is unpleasant, and we are motivated to eliminate that aversive state. One way to do that is to help the person in need. By eliminating the victim’s pain, we eliminate our own aversive arousal. Helping is an effective way to alleviate our own discomfort.

As an egoistic model, the arousal: cost–reward model explicitly includes the cost/reward considerations that come into play. Potential helpers will find ways to cope with the aversive arousal that will minimize their costs—maybe by means other than direct involvement. For example, the costs of directly confronting a knife-wielding assailant might stop a bystander from getting involved, but the cost of some indirect help (e.g., calling the police) may be acceptable. In either case, the victim’s need is addressed. Unfortunately, if the costs of helping are too high, bystanders may reinterpret the situation to justify not helping at all. We now know that the attack of Kitty Genovese was a murderous assault, but it may have been misperceived as a lover’s spat by someone who just wanted to go back to sleep. For some, fleeing the situation causing their distress may do the trick (Piliavin et al., 1981).

The egoistically based negative state relief model and the arousal: cost–reward model see the primary motivation for helping as being the helper’s own outcome. Recognize that the victim’s outcome is of relatively little concern to the helper—benefits to the victim are incidental byproducts of the exchange (Dovidio et al., 2006). The victim may be helped, but the helper’s real motivation according to these two explanations is egoistic: Helpers help to the extent that it makes them feel better.

Altruistic help

Although many researchers believe that egoism is the only motivation for helping, others suggest that altruism—helping that has as its ultimate goal the improvement of another’s welfare—may also be a motivation for helping under the right circumstances. Batson (2011) has offered the empathy–altruism model to explain altruistically motivated helping for which the helper expects no benefits. According to this model, the key for altruism is empathizing with the victim, that is, putting oneself in the shoes of the victim and imagining how the victim must feel. When taking this perspective and having empathic concern, potential helpers become primarily interested in increasing the well-being of the victim, even if the helper must incur some costs that might otherwise be easily avoided. The empathy–altruism model does not dismiss egoistic motivations; helpers not empathizing with a victim may experience personal distress and have an egoistic motivation, not unlike the feelings and motivations explained by the arousal: cost–reward model. Because egoistically motivated individuals are primarily concerned with their own cost–benefit outcomes, they are less likely to help if they think they can escape the situation with no costs to themselves. In contrast, altruistically motivated helpers are willing to accept the cost of helping to benefit a person with whom they have empathized—this “self-sacrificial” approach to helping is the hallmark of altruism (Batson, 2011).

Although there is still some controversy about whether people can ever act for purely altruistic motives, it is important to recognize that, while helpers may derive some personal rewards by helping another, the help that has been given is also benefitting someone who was in need. The residents who offered food, blankets, and shelter to stranded runners who were unable to get back to their hotel rooms because of the Boston Marathon bombing undoubtedly received positive rewards because of the help they gave, but those stranded runners who were helped got what they needed badly as well. “In fact, it is quite remarkable how the fates of people who have never met can be so intertwined and complementary. Your benefit is mine; and mine is yours” (Dovidio et al., 2006, p. 143).

Conclusion

We started this module by asking the question, “Who helps when and why?” As we have shown, the question of when help will be given is not quite as simple as the viewers of “What Would You Do?” believe. The power of the situation that operates on potential helpers in real time is not fully considered. What might appear to be a split-second decision to help is actually the result of consideration of multiple situational factors (e.g., the helper’s interpretation of the situation, the presence and ability of others to provide the help (i.e., diffusion of responsibility), the results of a cost–benefit analysis) (Dovidio et al., 2006). We have found that men and women tend to help in different ways—men are more impulsive and physically active, while women are more nurturing and supportive. Personality characteristics such as agreeableness and the prosocial personality orientation also affect people’s likelihood of giving assistance to others. And, why would people help in the first place? In addition to evolutionary forces (e.g., kin selection, reciprocal altruism), there is extensive evidence to show that helping and prosocial acts may be motivated by selfish, egoistic desires; by selfless, altruistic goals; or by some combination of egoistic and altruistic motives. (For a fuller consideration of the field of prosocial behavior, we refer you to Dovidio et al. [2006].)

Outside Resources

- Book: Batson, C.D. (2009). Altruism in humans. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Book: Dovidio, J. F., Piliavin, J. A., Schroeder, D. A., & Penner, L. A. (2006). The social psychology of prosocial behavior. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Book: Mikuliner, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2010). Prosocial motives, emotions, and behavior: The better angels of our nature. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Book: Schroeder, D. A. & Graziano, W. G. (forthcoming). The Oxford handbook of prosocial behavior. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Institution: Center for Generosity, University of Notre Dame, 936 Flanner Hall, Notre Dame, IN 46556.

- http://www.generosityresearch.nd.edu

- Institution: The Greater Good Science Center, University of California, Berkeley.

- http://www.greatergood.berkeley.edu

- Video: Episodes (individual) of “Primetime: What Would You Do?”

- http://www.YouTube.com

- Video: Episodes of “Primetime: What Would You Do?” that often include some commentary from experts in the field may be available at

- http://www.abc.com

News Article:

Wong, J. C. (2016, November 22). Dakota Access pipeline protester “may lose her arm” after police standoff. The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/nov/22/dakota-access-pipeline-protester-seriously-hurt-during-police-standoff-standing-rock