Chapter Four: Navigating Disengaged and Engaged Thinking and Heidegger’s Meditative Thinking

Part One: Disengaged and Engaged Thinking

Readings Included in the Chapter:

“Engaged Thinking for Conflict Processes” by Robert Gould

“Engaged Writing: Mediating Inner and Outer Narratives by Robert Gould

Introduction:

Why should conflict facilitators think about their thinking? Many conflict workers are trained to hold and enforce the process, and let the disputants work through the differences that they have with each other. Often, the disputants are encouraged to find common ground amongst their contrasting or conflicting interests. Once this common ground is found, then a resolution or strategy can be developed that helps them work productively together, whether in the workplace, neighborhood, interest group, or home. In all of this work, why is it necessary to examine, or worry about, the kind of thinking that is occurring within the disputants or the process facilitator?

This objection to thinking about our thinking, within the techniques of conflict facilitation, is reasonable. Consequently, many conflict-process trainings focus on just those techniques, with no need to go deeper. However, I suggest that we can improve our ability to positively facilitate conflicts of many different types, if we examine the different ways to think about thinking. In the following, I examine groupthink, critical thinking, contextual thinking, continuum thinking, engaged thinking, and meditative thinking because I believe that our knowledge of these ways of thinking can help us improve our ability to facilitate conflict processes.

Types of Thinking:

Groupthink: Thinking like the group thinks, without thinking for oneself.

Critical Thinking: Thinking for oneself to avoid groupthink.

Engaged Thinking: Thinking together, while also thinking for oneself.

Contextual Thinking: Being mindful of the context of our thinking and the thinking of others.

Continuum Thinking: Avoid thinking in polarities by thinking along continua.

Meditative Thinking: Following Heidegger’s advice to:

— Meditate on the notion of “releasement from things.”

— Maintain an “openness to the mystery.”

— Get comfortable with paradox, “what at first sight does not go together at all.”

Key Dilemma of Part One: Is it possible to genuinely think together with others, or is the perception of connected thinking just an illusion or a coincidence?

Example to help us work through this dilemma:

Once in a while, I participate in a brainstorming process with colleagues, where the ground rule is that we will just share ideas, without judging them. This collaborative process is intended to generate fresh perspectives on a problem and fresh solutions to consider. I have often wondered if brainstorming is really an example of “collectively thinking together,” or whether participants share their individual critical thinking, hoping that their perspective or solution is the best. It might appear to be a collaborative process, but inside each of our minds, we still might be competing with each other. To be an authentic collaborative process, each participant needs to think that all of the other participant’s perspectives and solutions are as good as mine, maybe better. Is this ever the case?

Engaged Thinking for Conflict Processes:

1. How do different kinds of thinking help or hinder the process of navigating difference and dilemma?

This chapter addresses how our thinking can get in the way of navigating difference and dilemma. If we are disengaged from other peoples’ differences, we cannot fully connect with them. We must be able to connect and engage with these differences, and not deny or overlook them. It is a fantasy that everyone is, or should be, the same as us. Even identical twins have differences in how they internalize the cultures around them. We may meet someone who appears to be our “soul mate,” but we eventually find out that they are not really identical with us. We have both similarities and differences with everyone, and they must both be engaged, or we will not fully connect with each other.

2. How do logical and critical thinking help us overcome groupthink, but still pose a hindrance to the process of navigating difference?

In addition to the problems of connection and disconnection, explored in the previous chapter, we need to explore the limits of logical and critical thinking or thinking for oneself. Logical thinking is important in areas of thought, where one can draw a straight line between premises, assumptions, and causes to conclusions, implications, and effects. However, much of our thinking is not quite so linear! (and the world itself is often non-linear and multi-causal).

We often find ourselves thinking within narratives, narrative structures, specific contexts, with rather fixed mindsets and frames of reference. These overarching influences on our thinking are hard to isolate, so that they could be put into a logical formula. Sometimes, we are completely unaware of these overarching influences because they can be so deeply embedded in our cultures and subcultures.

Critical thinking is an important skill because it points to the sometimes-distracting influences on our thinking, like fallacies, unwarranted assumptions, rhetorical ploys, irresponsible skepticism, peer group conformity, and exposure to specific audiences or groups.

In our mainstream culture, we almost inevitably learn to think like the members of our identity group. This groupthink is dangerous because it can force group members to ignore their own individual experiences, emotions, and thoughts, in favor of the ideology of one’s group. It is not easy to escape one’s own groupthink.

Personal Story: As a professional academic, I know that I can fall into groupthink myself. My philosopher colleagues have impressed on me the view that other academics, from other disciplines, often have inferior views and flawed research. In addition to this, I have been trained to think that students can easily become distracted by their social lives, occasionally cheat on their tests and homework, and at times, try to charm teachers into giving them good grades. I need to make an ongoing effort to avoid being influenced by this academic groupthink, and treat each colleague and student with respect and an open mind.

3. Why does the field of informal logic have an obsession with fallacies as irrational, when they can often be reasonable?

In my experience, when fallacies are defined in a certain way, they can certainly point out common thinking mistakes, but they can also be accurate.

For example, amongst all of the fallacies within informal logic, the ad hominem fallacy is typical in its limitations. Whereas, it accurately describes the problem of criticizing the person giving a viewpoint, rather than criticizing the viewpoint itself, it seems to ignore that the person’s identity may, correctly, play a role in forming their viewpoint.

Case Study: Editorial: “Look to Past Cougar Management to Help” by Jim Akenson

The Oregonian, January 25, 2019

“The fatal cougar attack on a hiker in the Mount Hood National Forest last year was a tragic thing. Evidence indicated that the cougar was a female that was in good health. Is this a surprise? Not really.

Cougar populations are at all-time highs across Oregon. Experts currently estimate a population of about 6,400 cougars compared to an estimate of less than 3,000 in the mid-1990s. Some reasons for the expansion are biological, some are social and much is connected to management capabilities and practices. We need to find a way to return to this socio-biological balance, and looking to the recent past might just be the best bet: Back to when hunting with hounds was a legal and effective management tool in Oregon.

The effects of this population growth are alarming and lead to other changes. Prey animals, specifically deer, relocate to more areas developed by humans to avoid risk, drawing in more cougars searching for the next meal.

Hunters and state wildlife managers report that deer are now less abundant in the mountain, high desert and canyon regions of our state. Meanwhile, Oregon cities are wrestling with the number of deer inhabiting city limits, and cougars are showing up in backyards and schoolyards.

As cougars become more comfortable in human-altered landscapes, the chance of negative encounters with humans, as well as pets and livestock, increases.

So, what is the solution? More intensive cougar management through various hunting techniques.

According to the 2017 Oregon Cougar Management Plan, the success rate for 2016 cougar hunters was 1.9 percent, with 13,879 people reporting they had hunted cougars. Contrast that with 1994 data — the last year dogs were allowed in conservatively controlled, limited-entry cougar hunting. Those figures showed that 358 people hunted cougars and harvested 144 for a success rate of 40.2 percent.

The bottom line is that hunting with dogs is more efficient and provides wildlife managers a reliable tool for maintaining the cougar population within their objectives.

Oregon’s cougar management and record-keeping are divided into six zones, each assigned a desired harvest quota to keep the population in balance. Employing the current limited management methods, only one of the six zones has met the harvest quota in recent years.

A criterion for quota establishment is the frequency of complaints. By far, the most cougar complaints are recorded on the west side of the Cascades, where the bulk of Oregonians live. More than 350 cougar complaints per year were received during the last decade in two zones in that area. Unfortunately, this recording system was not initiated until 2001, so we don’t have data for the time before the dog ban of 1994.

We do have records for administrative actions connected to human safety and pet conflicts before and after the dog ban of 1994. For eight years before the ban, they averaged four per year. Seven years after the dog ban, complaints increased nearly seven-fold to 27 per year.

Oregon does have a program wherein highly vetted “houndsmen” are permitted to lethally remove cats to reduce human conflict and bolster deer and elk survival. These agents work closely with Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife biologists. Even with this program in place, cougars are steadily increasing in Oregon, where hunting them is very impractical without the aid of dogs.

Currently, the law authorizing the agents is up for renewal, and hopefully it will receive legislative support and be applied more broadly to reach zone harvest quotas and to help curb cougars’ increasing population across the state.”

This editorial seems reasonable, but it leaves out some information.

Missing Information: The Mountain Lion Foundation and other groups counter Akenson’s view with the following concerns:

Hunting dogs can gravely terrorize cougars and their young, injuring them, and leaving them cornered or run off from their territory. Hunting dogs can injure or kill other wildlife, and even injure or kill each other, or even strangers who get in their way. These animals are bred to kill without mercy. Trained cougar hunters kill with efficiency and mercy. Consequently, it is inhumane for dogs to be used in hunting cougars, and it is much more humane for trained and certified hunters to cull any overpopulation of cougars, which has been the given practice in Oregon since 1994.

Analysis: There is certainly room for a debate on this topic, but readers need to have complete information. Given that “Jim Akenson is a wildlife biologist and conservation director for the Oregon Hunters Association. Akenson is also a book author and has invested much of his career in researching the Northwest’s predators. He lives in Enterprise [Oregon],” we might suspect that he would be sympathetic to the idea of hunting cougars with hunting dogs. We could suspect this, without reading his article, by simply knowing his affiliation with hunters. Making this assumption, without reading his editorial, would be an ad homonym attack on his viewpoint. However, in reading his editorial, we find that he does not respond to the longstanding criticisms of hunting cougars with dogs. Therefore, it seems that his affiliation with fellow hunters is driving his viewpoint. My point is that identity often plays a strong role in what we believe to be true, and in how we present our views to others. Sometimes, we employ ad homonym dismissals of arguments that simply trigger our contrary beliefs. Other times, we properly take identity into our consideration of our own and others’ views.

Informal and Formal Logic: The field of informal logic can be as true/false oriented, as the field of formal logic. These fields of philosophy want to convince us that fallacies are false, just as groupthink is false, but there can be some truth embedded in both. Oddly, the fields of logic and critical thinking can, at times, themselves, be examples of groupthink.

Like all overgeneralizations and stereotypes, there is some truth to groupthink conclusions, but most damaging, these overgeneralizations can have a vitality of their own, and professors struggle to get out of the grips of these group thoughts, largely because they can serve as self-congratulations to the professors, themselves. “We are the smart ones doing the important work. Other professors are not as smart, and their work is not as good. Students just want earn degrees by doing the least work.”

Likewise, students have similar groupthink perceptions about other students and professors. It is a quite challenging to avoid jumping to conclusions about students and professors because it takes so little time out of one’s day! To really get to know students and professors, who think differently than our identity group, takes a lot of time that most of us do not have at our disposal. Therefore, these group-thoughts can live on for generations, until some serious research has the power to challenge them. The challenge here is to learn to think for oneself, and resist letting our identity group do our thinking for us.

4. What is engaged thinking, and how does it help us navigate engagement and disengagement?

Since there is a problem with critical thinking, in isolation of a true diversity of thoughts, we need to come up with a way to overcome this problem. As explained above, critical thinking is needed to resist the conformity of group-thinking, generated by our identity group, assuming that one’s identity group is not diverse in its thinking. One’s identity group can have cultural, racial, ethnic, and gender diversity, and still have groupthink, if thinking differently about core features of identity is not tolerated.

On the other hand, an identity group that is truly diverse in terms of gender identification, race, sexual orientation, wealth, status, etc. can offer many perspectives to help broaden our thinking. One who is a critical thinker does not have the capacity to know these other perspectives, unless one engages with these diverse others, and listens to their experiences, thoughts, and begins to understand where they came from, and empathize to some degree with their viewpoints.

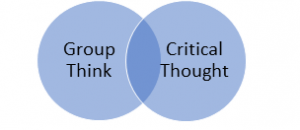

I call this engagement by the name, engaged thinking. Blythe McVicker Clinchy calls it “connected knowing.” I have illustrated the connection between group-thinking and critical thinking, below. Remember that the engaged thinking, that the arrow points to, is when group members are critical thinkers, who are also committed to thinking together across their differences.

Also, remember that research-based groupthink is the fabric of knowledge, going forward. However, research can be proven wrong, so one must always have a skeptical eye on the received knowledge of any cultural history, particularly one’s own. On the other hand, we also need to navigate between our skeptical eye and our eye of compassion to be sure that we give others our empathy and understanding, even when we don’t agree with them.

The overlapping section of the Venn diagram circles, above,

represents engaged thinking, where we can think together

with others, without sliding into groupthink, nor sliding into a kind

of individual thinking that discounts the value of other’s thoughts.

SUMMARY OF GROUP THINK, CRITICAL THINKING, AND ENGAGED THINKINGGroupthink: Thinking like the group thinks, without thinking for oneself.

Critical Thinking: Thinking for oneself to avoid groupthink.

Engaged Thinking: Thinking together, while also thinking for oneself.

5. How does engaged writing help us with engaged thinking?

Engaged writing is an internalization of the process of engaged thinking. Rather than think with others, engaged writers engage across their internal differences, critiquing their own group think, along with critiquing the isolation of their own internal critical thinking.

6. What is contextual thinking?

If we use the metaphor of a map and territory, then the world of direct experience is the territory or context, and our abstractions and generalizations of that world are the map. In the following, I share an example of the contrast between a map and the territory:

On a recent camping trip, at a lake north of Mt. Hood, I talked with the camp host, who was contracted by the forest service to verify their map, created the year before. I was assuming that the map would be accurate, as it was so new. However, the camp host pointed to a number of spots on the map that were wrong: “no road here; no trail here; no creek here, etc.” The map needed be corrected by the camp host’s direct experience of the territory, so that the map could properly guide us through the territory.

Contextual thinking is based on our direct experience of the phenomena that have been abstracted and generalized in our language and research. The abstractions and generalizations are supposed to guide our lives, but they must correspond with our direct experiences. Otherwise, we will be misled. In other words, we live in a non-reducible world, that cannot be fully experienced through indirect abstractions and generalizations. We need the maps to guide us, but maps are always somewhat incomplete and inaccurate, so they must continually be updated and verified by our direct experiences.

In psychology, we learn about various mental disorders, so that we can diagnose and treat patients and clients with these disorders. However, it becomes a little too easy to see the patient or client in terms of their disorder (“He is a manic-depressive.”), not as a person who struggles with a certain issue at a certain time (“At this time, he is struggling with manic-depressive episodes”. In other words, we don’t want to map his territory in a fixed, inflexible way. We want his changing experience to change how we think about him, so that he is not stuck in a label. As the territory changes, the map needs to change.

In public health, before the book, Our Bodies, Ourselves, was published in 1976, women’s bodies were considered to just be a variant of men’s bodies. Physicians’ diagnostic maps saw the body of a women as the same general body as men, with some variations. However, paradigm-breaking research, and the direct experience of women, showed that the map of a woman’s body should be different than the map of a man’s body.

What is more true, direct experience or our concepts?

Analytic philosophers seem to think that some of our concepts can be shown to be true, and other concepts, derived from the true ones, can be indirectly true. On the other hand, existential philosophers seem to think that our direct experiences are true, and that our concepts need to follow the lead of our experiences.

In my opinion, contextual thinking can best approximate the truth of the matter, when it balances insights from maps with insights from direct experience. Ultimately, the truth of the matter must be judged by its coherence and consequences. On my view, contextual thinking provides an important mode of reflection, but other modes, like mystical experiences and revelations are important, as well. We best understand the world when we maximize the modes of understanding and experience that we use in our daily navigations of thought and action.

7. How does contextual thinking get us unstuck from abstract thinking, oversimplifications, and overgeneralizations?

Contextual thinking provides an alternative perspective on our world that is not over-controlled by our concepts and abstractions. Sometimes abstractions can be useful, sometimes not. Sometimes context can be useful, sometimes not. It would not be useful to get stuck in either mode, without the other mode. Getting unstuck requires developing the skills of each kind of thinking, so one can navigate with both. One needs to see both the forest and the trees, not just the forest without the trees, nor the trees without the forest.

8. What is ordinary language thinking, and how does it help us escape the confines of jargon and unnecessary abstraction?

Ordinary language thinking is a mode of thinking that avoids philosophical or academic jargon, and uses language that ordinary people use to communicate. These ordinary ways of communication may offer insights about life, and the world, that are missed by abstractions that may be academic jargon or that can overgeneralize aspects of life and world.

9. What is continuum thinking, and how does it get us unstuck from polar thinking?

In English and other languages, we have many polarized categories: good/bad; happy/sad; beautiful/ugly; strong/weak; leaders/followers; dominant/dominated; correct/incorrect; and on and on.

However, there are many gradations between these polarities that form continua. If we learn to avoid polarized thinking that is filled with polar opposites, then we are using continuum thinking. In our work with conflict, it is much better to be continuum thinkers, and encourage continuum thinking amongst disputants. This shift from polar thinking to continuum thinking creates a space for understanding and navigating differences, without triggering our limbic systems into emotional flooding.

10. What is paradoxical thinking, and how can thinking opposites at once help us overcome cognitive dissonance?

Cognitive dissonance is the uncomfortable feeling of experiencing internal, irreconcilable, differences.

As an example, we may care deeply for a family member that we have a hard time being around because of past resentments, and the inability of forgiveness to heal these grudges. So, internally, we are both pulled toward a certain family member, while also feeling pushed away. Managing cognitive dissonance commonly pushes us toward one side of the difference, and away from the other side. We might avoid the person as much as possible, or we might continue to try to build bridges with them more regularly.

Paradoxical thinking is achieved when we develop the ability to think opposites at once. Rather than default to one side, or the other, we can find a way to navigate the tension between the two opposing experiences. In the example, above, we acknowledge that we are both pulled toward and repelled by a family member, so we act in such a way to achieve civility in our relationship with that person, while protecting ourselves from being toxified by overexposure to them.

11. What is flexible thinking, and how does it help us navigate between liquid and solid knowledge?

Solid knowledge is the kind of bedrock knowledge that seems to be unchangeable. The sun rises and sets as the earth rotates. Other bits of knowledge are not so stable, such as the recommendation that breathing calmly is generally a good idea—except when it isn’t. Bedrock knowledge is referred to a solid knowledge. A lot of academic effort goes into finding solid knowledge. Sometimes, people propose certain bits of knowledge, like “the industrial/technological age has been a great idea for the people and the planet.” Well, yes and no, depending on your view of “good.”

The technology advancements in public health have generally been positive. However, coal mining and pollution has been big negatives for the environment. This kind of claim is referred to as liquid knowledge that is true or false, depending on the context. We need to use flexible thinking to navigate the goodness and badness of the industrial/technological age. Claiming that this age is all good, or all bad, is an example of inflexible thinking, which can be misguided and dogmatic.

12. How can we mediate between inner and outer narratives?

When we reflect on our lives, we often construct inner narratives, or stories, about how our life has been developing. These life stories are both personal and social. Personal because we invent them, and social because the outer narratives, that surround us, also influence our inner narratives. The problem of navigating the inner and outer narratives is that sometimes the outer narratives are too harsh on us, or sometimes they build us up beyond justification. Likewise, sometimes our inner narratives are two harsh on us, or exaggerated our worth, talent, or virtues beyond reason.

Navigating our inner and outer narratives can be difficult because there is no objective narrative to guide us. How do we measure our success? How do we measure our failure? In the absence of an objective story of our life, I recommend consulting those who care about us, and also those who are likely to have different perspectives. Meshing these stories can help create a balance of our sense of success and failure. A helpful (but often misattributed) saying suggests that, “success is walking from failure to failure with no loss of enthusiasm.”

13. Besides our thinking and talking to each other, how do other expressions of self, culture, environment, genetics, narrative, and group dynamics help or hinder the process of navigating difference?

The various ways that people communicate within themselves (thought and mood) and others (talk and affect) include various kinds of art, music, marketing, media, and the patterns of peer, family, neighborhood, and workplace interactions. Each of these influences how we think or react to each other. Navigating all of these interactive modalities is daunting. We must be extraordinarily reflective to keep track of these influences, individually and in aggregate.

Personal Reflection: I love to have fun in life, though I don’t have a clear inventory of all of the ways that “living a fun life” has emerged as a lifelong goal. My parents, peers, neighbors, and workmates all have gravitated towards having fun. We joke with each other, we recreate, in a wide variety of ways, to have fun.

I think of my work as a kind of fun, though it can be stressful all too often. One of my mentors, Don Levi, urges me not to think of my work as fun because it takes so much sacrifice and pain to accomplish philosophical projects. My marriage is also fun, but it can often be stressful.

I also identify with the surfing and beatnik/hippy cultures of the 1960s because members of those cultures have a commitment to a relaxed life, filled with fun and physical activity. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, as a windsurfer, I felt more relaxed and happier than at many other more stressful times of my life. I wish I could find that sweet spot again!

Then there is the quest for meaning and success in my life to give it richness, not embodied by wealth. This ambition is part of my generation (baby boomers), though for many baby boomers, the quest for wealth has overtaken the quest for meaning. Certainly, other generations also have a quest for these three ambitions to varying degrees. Perhaps these quests are more broadly cultural and historical amongst those of us caught up on the cutting edge of civilization. I have found meaning in helping students succeed, teaching, writing, and being a collaborative colleague, husband, step parent, grandparent, and neighbor.

However, as a Northern European white male, I do not identify with the rapacious aspects of modern civilization, and its toxic masculinity. Rather, I identify with indigenous people’s philosophy and their commitment to maximize human harmony with the rest of nature. Where did I get that part of me? I am 0.2% Native American, but not a tribal member, so I don’t have a genetic or cultural connection that accounts for this identity. I have had a deep exposure to environmentalism and have worked with tribes on military/tribal conflict resolution and to help restore Oregon tribes’ federal recognition, after the termination of their tribal status during the 1950s. Also, as a beatnik/hippy, I absorbed a cultural influence that regenerated respect for Native American beliefs and practices in the 1950s and 1960s.

All of these influences, which I dredge up from my reflections, provide elements of my identity that both harmonize together, and provide tensions within me, and with those around me. The various narratives, art, music, marketing, media, and the patterns of peer, family, neighborhood, and workplace interactions, create the inner and outer landscape of my life. Navigating it, like flying in an aircraft, sometimes goes smoothly, and sometimes it is filled with turbulence. Welcome to life!

Gould Essay:

Engaged Writing: Mediating Inner and Outer Narratives

Keeping the Strength of One’s Argument, while Avoiding the Alienation of One’s Readers

“[A]rgumentation is a good way to inquire, to move into new selves, new modes of selfhood, new ways of being in and understanding the world . . . [making argumentation less argumentative] can also enable inquiry, the discovery of what is new.” (p.267, Crosswhite)

Abstract: Writing is filled with at least two powerful conflicts. First, the writer, in presenting an argument, must struggle with her internal doubts and objections. Second, the writer must struggle to challenge her reader without alienating him. No wonder writers are often blocked by these inner and outer conflicts. To simplify matters, the writer is tempted to simplify the process by asserting an argument in a take-no-prisoners style: right vs. wrong, correct vs. incorrect. Unfortunately, this polarized approach can alienate the reader who has objections, and mask the worries that the writer might have. I suggest a way to mediate both the inner and outer conflicts that writers face, so that more readers are engaged, and the writer presents more of herself—doubts and all. The conflicts implicit in argumentation are a good thing because they pose unveiled challenges to our thinking. However, we can ill afford to argue in such a way that alienates our readers by minimizing, oversimplifying, ridiculing, ignoring, or not understanding their concerns and potential objections. Successful writing does not manipulate the reader or demonize opponents; rather it persuades by compassionately engaging a wide variety of readers and points of view. Engagement requires one’s ability to help the reader be sufficiently validated so that she feels included in a conversation, not alienated from the dialogue.

Text: In the best case of dialogue, we try to bridge any division between us by trying to make our views as compatible as possible with what is important to each other. In this way, the gulf between us is made as narrow as possible, and even if we don’t immediately come to a resolution of our differences, we have made it possible to understand each other. In the best case of writing, we imagine the possible alternative points of views of our readers, and incorporate them into our inner meditations.

The problem with writing, as with dialogue, is that we might not seek out disagreement, and instead keep our conversations and consultations within a narrow range of opinion. At the one extreme, adversarial writing is hostile. At the other extreme, writers avoid conflict entirely by framing controversial topics as “clarifications,” “new models,” and “new ways to organize information.”

Too often, academic papers are written in an adversarial style, depending on the drama of correct against incorrect or good against bad. Because of this kind of polarization—even demonization—adversarial writing does not engage the opposition; rather it disengages or alienates readers who feel labeled as “wrong” or “bad” because of their disagreement. Some contemporary theorists are pushing the practice of critical writing towards a more compassionate understanding of the diversity of one’s audience (Crosswhite, Chafee). In doing so, they are suggesting that one can be more persuasive when one validates different insights and perspectives, than when one hammers home one’s singular argument.

In the following, I suggest an engaged writing style that, first, makes a strong case for both sides, rather than trying to defeat the opposition by focusing on its weaknesses. In this way, the opposition feels respected, and both sides are pushed forward in their thinking. Secondly, I suggest that this engaged writing style creates new ways of thinking by engaging the tension between opposing insights and points of views. This creative feature moves beyond merely addressing and validating a diverse audience by using the conflict to generate possible new approaches to a wide variety of dilemmas.

Such a conflict can be embraced by the way we approach the inner meditation of our writing. Ideally, writing is where we discover our point of view by mulling over a variety of views, concerns, and objections. I often find that the position that I started with is, quite surprisingly, not the position that I end with. In conducting this inner meditation, we look for the insights from a variety of perspectives. The weakness of writing, in comparison to live dialogue, is that we are not finding out about other perspectives directly from the actual people who hold them. In a live discussion, we can be corrected in our misinterpretations of other views. Interestingly, this corrective process entails moving beyond what is said to what is meant. Writers must make the effort to dig for a deep understanding of the insights behind perspectives that, on first glance, do not seem to offer any insight at all. It is far too easy, and mistaken, to suppose we can glean others’ views by working solely with just the words said or written. Understanding is a process of discovery, not merely quoting others.

We must never underestimate the value of paraphrasing others’ points of view and to check with them if the paraphrase is accurate. Of course, this is difficult if the original writer or speaker is not available to us; so, it is no wonder that there is such a variety of interpretations of long-dead thinkers.

To overcome the difficulty of capturing others’ views—or even our own—we must write—and rewrite—upon further inner consideration and consultation with others. By embracing our own doubts and conflicts about our own work, along with the concerns and objections of others, we continue to refine our work in such a way that we better engage both ourselves and others. My point is that we need to be transparent about those conflicting inner considerations and outer consultations by working them into our writing style. The key value of the engaged writing process is that the tension between different points of view can be quite creative. This creativity can lead us to surprising conclusions or recommendations for further thinking. In the following, I explore examples of navigating between absolute and relative truths on the topics of murder, gang initiations, marijuana use, and faith healing. I show how one might be tempted to merely argue for one view against a seemingly weaker view; then, I show how a more balanced approach can help us move forward by embracing conflict innovatively.

Using the adversarial style, one might try to eliminate the idea that truth is relative by showing that it is self-contradictory. This follows from the assumption that the statement, “truth is relative,” functions as an absolute truth and, therefore, must be self-contradictory and false because any claim to absolute truth violates the principle that truth is relative. However, the insight behind the statement, “truth is relative,” has not been engaged in this critical reply. Therefore, some effort is required to capture the insight. On further consideration, we could restate the principle in the following way: “If a truth significantly depends on contextual features, then the truth is relative or grounded in those features that must be carefully considered.”

An example of this is the claim that “killing endangered species is wrong.” Upon careful consideration of one contextual feature, for example, an incurable virus carried by some members of the species that threaten the entire population, we can rather easily conclude that it may be necessary to kill those ill members of the species that threaten the existence of all of the species. Obviously, a quarantine would be more humane, but it some cases, like certain species of whales, may not be possible.

Alternately, some truths do not significantly depend on contextual features, so such truths are not relative or grounded, and are, therefore, absolute. For example, “murder is wrong.” This is true partly because murder is defined as wrong. We make the distinction between murder and justified homicide by an understanding that murder is unjustified and certain homicides are justified. The problem with this justification is who judges whether a killing is justified or not? Certainly, we need to look at the context. Self-defense might entail homicide, but is would be justified if there were no seemingly viable nonviolent alternatives. The viability of nonviolent alternatives depends on contextual features. For example, was it a home-invasion that was lethally threatening? Cultural perspective is also important. Some cultural or sub-cultural groups demand revenge killings. Some governments mandate political assassinations. Do those considerations make homicide justifiable? These circumstances make navigation of the distinction between murder and justifiable homicide difficult indeed. Therefore, while it may be easy to assert that murder is wrong, it may be quite difficult to determine if a homicide is murder.

Following this, the claim that a homicide is murder depends on contextual features (no nonviolent options); therefore, such a claim’s truth is relative. In this case, we have an absolute truth (murder is wrong) partnered with a relative truth (homicide is wrong). This partnership represents a kind of synthesis of absolute and relative truths—a surprising possibility.

Turning to a second topic, we might wonder about the relativistic view that the street gang initiation called, “jumping in,” can be considered a kind of rite of passage in modern street contexts. Using the adversarial style, one might argue that giving new gang members a severe beating, along with gang indoctrination, is actually a kind of traditional youth-to-adulthood rite of passage. This view follows Malidoma Patrice Some’s comparison of American gang initiations and African rites of passage.

This view opposes the opinion that rites of passage are not so fluid that they can be applied to street life. This view is that rites of passage must meet strict standards, and cannot be made relative to context. Therefore, gang rites are merely idiosyncratic membership initiations that only mimic more formal and meaningful rites of passage, no more significant than a fraternity hazing. However, if one takes this objection more seriously, it can be argued that a true rite of passage transmits the wisdom of the culture, not merely a membership in a violent, predatory subgroup. The deeper insight about gang initiations may not depend on whether they are, technically, built on traditional rites of passage. On further thought, gang initiations may help us understand that young gang members are looking for some transition from youth to adulthood, and that gang membership with the mentoring of adult gang members, offers youth the only available transition in certain communities. This insight fits my experience discussing this matter personally with gang-affected youth.

The surprise, in this instance, is that our worry about the question at hand (Is jumping-in really part of a rite of passage?) is not as important as the larger challenge of finding appropriate mentors for gang-exposed youth. We might define “jumping in” as a legitimate rite of passage—or we might not. However, the deeper concern is that young people are given opportunities for nonviolent rites of passage by nonviolent mentors for nonviolent adult enterprises.

Using a similar relative-to-context approach, we might argue, adversarially, that marijuana should be legal because, when used recreationally, it creates only a mild, temporary impairment, and it has legitimate medical uses. Furthermore, criminalizing marijuana use has much greater social costs, in terms of prosecution, imprisonment, and eradication, than decriminalization. However, such a view does not address the risks of operating machinery while impaired, damaging lungs, potential addiction, and sending the message to youths that marijuana has no hazards. This more absolutist approach argues that any recreational drug should be avoided as much as possible because of its downsides.

A more balanced approach to marijuana could focus on the distinction between use and abuse. Just as alcohol has some physical and mental health benefits, when used appropriately, marijuana also seems to have some physical and mental health uses when used with discretion.

However, both alcohol and marijuana can be abused—and generate significant social costs. Criminalization of drug abuse does not seem to deter patterns of abuse, while generating huge social costs, just as prohibition did not significantly alter patterns of use and abuse of alcohol. Though prohibition lowered overall consumption, it created huge social expenses. The deeper concern generated by this discussion is why drugs of any kind are so often abused in our culture. What is it about our culture that drives people toward intoxicated recreation or abusive levels of self-medication? Ultimately, this deeper question is more important as our larger concern than the criminal status of a drug.

Starting from an absolutist approach, rather than the relativist approach developed in previous examples, one might frame the problem of faith healing by claiming that such practices, when they exclude medical intervention, amount to abuse, particularly amongst children who cannot make the adult decision to avoid medical care. The argument is simply that children die who could have been saved by medical intervention, so withholding this intervention is abusive. Following this determination, the law should be applied punitively to uphold a boundary against abuse.

However, this position does not take seriously the religious views and experiences of those who find faith healing compelling. First, they believe that the omniscient, omnipotent and omnibenevolent power of God is far more trustworthy that the mortal powers of the medical profession. Second, they believe that looking to medicine for help is showing doubt in God, rather than faith. In other words, these religious people feel that they must either trust God or trust human medicine, and that trusting human medicine demonstrates mistrust in God. Third, they have probably experienced many instances where prayer appeared to help people recover from illness.

When an adversarial stance is applied to this conflict, certain religious groups can feel that their faith in God and the power of prayer is trivialized. Furthermore, medical science advocates may not acknowledge how the many failures of medical practice undermine trust in those practices. The cycle of mistrust on both sides leads to the polarization of the conflict. Unfortunately, both sides are perceived within an either/or mode, not a both/and mode. Wouldn’t it be a vast improvement to reframe the conflict so that trust is affirmed for both modern medicine, as part of God’s creation, along with the power of prayer to affirm that the divine hand will be present in all of modern medicine’s practices?

The problem is, how can we get both sides of this argument to discuss this possible synthesis? I doubt that the punishment approach will produce such a dialogue. Rather, I think that such a discussion might best happen theologically. Doubtless, there are many strict fundamentalists who believe in the healing power of prayer, but still use of medical practice when appropriate. A productive discussion might well occur by bringing together these two kinds of believers in the power of prayer to discuss this issue with a common ground of religious fundamentalism. Discussions within the court system, the secular press, or even academe, cannot replicate the high validation level of two closely identified fundamentalist groups. This conclusion illuminates not only how we need to address those who object to our argument, but also that a productive discussion of this issue must involve people with the greatest common ground—with the greatest shared, relative context.

In the above examples, I have tried to demonstrate an engaged writing process that navigates through absolute viewpoints and points of view that are relative to context—with each transit illuminating new directions for our thinking. With these considerations, I now move to a discussion of the principles guiding the engaged writing style. Not surprisingly, this style has its origins in the practice of conflict resolution. This practice entails a number of different insights and techniques. The insights and practices that are of the greatest value to engaged writing are the ones that view conflict as an opportunity for all disputants to gain a kind of transformation or conscious change as an outcome of the conflict. The opportunity for transformation, offered through conflict, actually involves three different kinds of transformation. First, conflict can be an opportunity for self-transformation. Second, conflict can be an opportunity for one to transform one’s relationship with others. Third, conflict can be an opportunity for creating the conditions for the transformation of society.

When we think carefully about a controversial topic or issue, we automatically find ourselves within a conflict. All controversial issues involve at least two opposing perspectives. This conflict can be an opportunity for the three kinds of transformation mentioned above. However, certain conditions must prevail to enhance the opportunity for transformation. These conditions or principles, listed below, are central to the practice of engaged conflict resolution, as well as engaged writing and thinking.

• Be respectful of opposing claims to knowledge on the topic. Even though, initially, there may appear to be little to learn from a different view, disrespect will ensure that one finds little of value.

• Be direct in addressing another perspective. Do not get sidetracked by peripheral issues–or by the weak claims, or weak evidence, of disputants. Try to go to the heart of this issue and engage the strongest claims and strongest evidence for the opposing perspective.

• Take responsibility for both the strengths and weaknesses of your own opinion or position in the dispute. Do not be in denial about your view’s short-comings—or by its full potential for insight.

• Be trustful of other points of views. If you address an opposing view in a way that suggests that it is deliberately misleading, or that its advocates are deceitful, the opportunity for transformation will be slim to none.

• Be mindful of the difference between your experience and the experiences of others. People who have opposing perspectives may live in a world that is radically different from your own. Conflict can be the key to opening up a new world for you–and a new world for those with opposing views.

• Using the conflict creatively by the opening up of new worlds is key to the engaged process. Each step toward this goal is important, and perhaps necessary. Respect, directness, responsibility, trust, and mindfulness are the steps that create the possibility of new worldviews for both yourself and for your opponents.

These new worldviews are the basis for self-transformation, transformation of relationships, and social transformation because the expansion of consciousness to include new worlds is transformational to one’s core identity, values, and knowledge. Thinking carefully through a transformational process is quite different from merely thinking critically. In more traditional methods, one does not unlock the other’s world; rather, one only addresses the opponent’s words. In traditional critical thinking approaches, the goal is usually to find the weaknesses in those words, without going beyond them to discover a fuller perspective. All of which is to say that the traditional goal is to win, not to grow.

Another way of viewing the engaged thinking and writing process, in contrast to traditional critical thinking, is to see it as a way to think collaboratively, without the dangers of thinking in isolation, or having others do your thinking for you. If you merely win an argument, you may be thinking in isolation by defeating only your perspective of your opposition, rather than fully understanding another view. In such a case, one’s opposition will not be convinced, but rather they will feel that their view has been misunderstood, trivialized, or oversimplified.

If you allow the other side to win an argument, you may be letting the opposition do your thinking for you. If you are able to fully see a different perspective by gaining traction in their world–without losing traction in your world–you are in a position to give both sides of the argument something to think about. This involves collaborative or transformational thinking that has the following features:

• Multiple perspectives that are worth consideration.

• No tidy argument for one side aimed at defeating the other side.

• An emphasis on complexities and difficulties.

• Insights that are sometimes contradictory and paradoxical.

• An avoidance of theories and abstractions that seem too simple.

• Thinking that does not deny subjectivity and emotions.

• Viewing the problem in context, not isolation.

• Examples from real life, or from great literature or drama.

• Using the conflict creatively to generate new possible resolutions.

Perhaps the most important quality of engaged thinking and writing is the periodic return to the question, “What is this issue or controversy really about?” In order to answer this question, one needs to explore one’s frame of reference or one’s predispositions to the issue at hand. One needs to look for the deeper controversy or question. One needs to let the differing sides of the controversy help one gain a more sophisticated understanding of the issue. This form of cyclical inquiry becomes a method, as outlined below:

What is my first impression of what this issue or controversy is really about?

What is my deeper insight into what this is really about?

What evidence or world-view supports my insight?

What are the strengths and weaknesses of my insight?

What is a different, or opposing insight—its evidence and world-view?

What are the strengths and weaknesses of this different, or opposing, insight?

Can I create or discover a new insight by embracing the conflict, possibly combining the strengths of these different insights?

Given what I have learned, what is this issue or controversy really about?

As mentioned above, the field of critical thinking can sometimes focus too closely and narrowly on analyzing words, rather than trying to discover their underlining meaning or insight. Oftentimes, a critical analysis can seem like an attack on the weaknesses of the presentation, not the content. This attack can feel like an adversarial prosecution of a case, rather than a cooperative investigation into the matter. Such a cooperative investigation is based upon authentic compassion for the deeper concerns being presented.

What is the deeper worry being expressed?

What deeper controversy is being addressed?

This alternate approach feels more supportive, and less like an attack that must be repelled. It is my contention that more careful thinking and writing can take place in a supportive environment, rather than a hostile, adversarial environment. An argument can be asserted in a way that is both challenging and respectful—even transformational.