11 Chapter/Lecture 13 Personality Disorders

The purpose of this module is to define what is meant by a personality disorder, identify the five domains of general personality (i.e., neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness), identify the six personality disorders proposed for retention in the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) (i.e., borderline, antisocial, schizotypal, avoidant, obsessive-compulsive, and narcissistic), summarize the etiology for antisocial and borderline personality disorder, and identify the treatment for borderline personality disorder (i.e., dialectical behavior therapy and mentalization therapy).Learning Objectives

- Define what is meant by a personality disorder.

- Identify the five domains of general personality.

- Identify the six personality disorders proposed for retention in DSM-5.

- Summarize the etiology for antisocial and borderline personality disorder.

- Identify the treatment for borderline personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder.

Introduction

Everybody has their own unique personality; that is, their characteristic manner of thinking, feeling, behaving, and relating to others (John, Robins, & Pervin, 2008). Some people are typically introverted, quiet, and withdrawn; whereas others are more extraverted, active, and outgoing. Some individuals are invariably conscientiousness, dutiful, and efficient; whereas others might be characteristically undependable and negligent. Some individuals are consistently anxious, self-conscious, and apprehensive; whereas others are routinely relaxed, self-assured, and unconcerned. Personality traits refer to these characteristic, routine ways of thinking, feeling, and relating to others. There are signs or indicators of these traits in childhood, but they become particularly evident when the person is an adult. Personality traits are integral to each person’s sense of self, as they involve what people value, how they think and feel about things, what they like to do, and, basically, what they are like most every day throughout much of their lives.

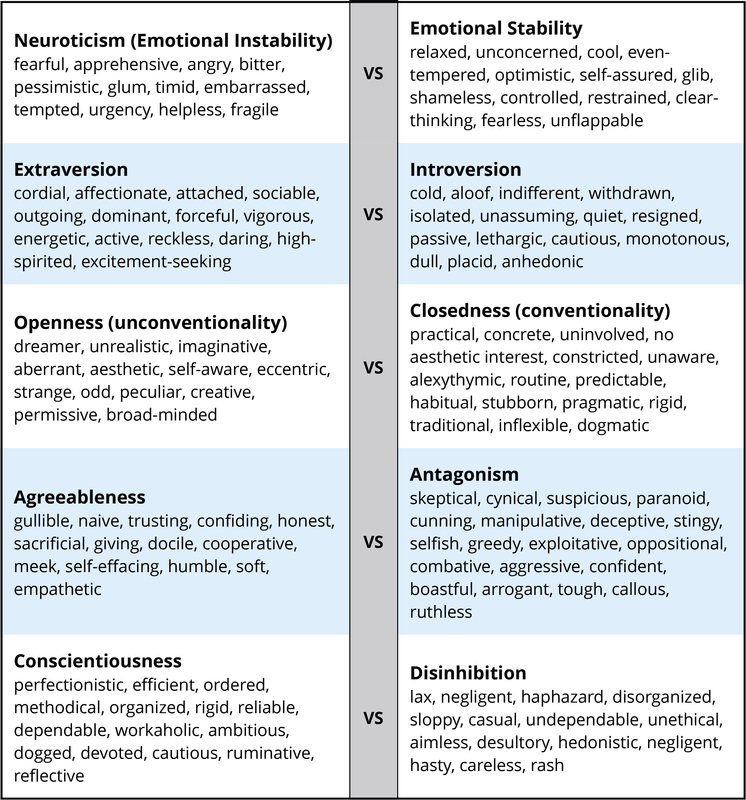

There are literally hundreds of different personality traits. All of these traits can be organized into the broad dimensions referred to as the Five-Factor Model (John, Naumann, & Soto, 2008). These five broad domains are inclusive; there does not appear to be any traits of personality that lie outside of the Five-Factor Model. This even applies to traits that you may use to describe yourself. Table I provides illustrative traits for both poles of the five domains of this model of personality. A number of the traits that you see in this table may describe you. If you can think of some other traits that describe yourself, you should be able to place them somewhere in this table.

DSM-5 Personality Disorders

When personality traits result in significant distress, social impairment, and/or occupational impairment, they are considered to be a personality disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The authoritative manual for what constitutes a personality disorder is provided by the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the current version of which is DSM-5 (APA, 2013). The DSM provides a common language and standard criteria for the classification and diagnosis of mental disorders. This manual is used by clinicians, researchers, health insurance companies, and policymakers. DSM-5 includes 10 personality disorders: antisocial, avoidant, borderline, dependent, histrionic, narcissistic, obsessive-compulsive, paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal. All 10 of these personality disorders will be included in the next edition of the diagnostic manual, DSM-5. This list of 10 though does not fully cover all of the different ways in which a personality can be maladaptive.

Description

Each of the 10 DSM-5 personality disorders is a constellation of maladaptive personality traits, rather than just one particular personality trait (Lynam & Widiger, 2001). In this regard, personality disorders are “syndromes.” For example, avoidant personality disorder is a pervasive pattern of social inhibition, feelings of inadequacy, and hypersensitivity to negative evaluation (APA, 2013), which is a combination of traits from introversion (e.g., socially withdrawn, passive, and cautious) and neuroticism (e.g., self-consciousness, apprehensiveness, anxiousness, and worrisome). Dependent personality disorder includes submissiveness, clinging behavior, and fears of separation (APA, 2013), for the most part a combination of traits of neuroticism (anxious, uncertain, pessimistic, and helpless) and maladaptive agreeableness (e.g., gullible, guileless, meek, subservient, and self-effacing). Antisocial personality disorder is, for the most part, a combination of traits from antagonism (e.g., dishonest, manipulative, exploitative, callous, and merciless) and low conscientiousness (e.g., irresponsible, immoral, lax, hedonistic, and rash). See the 1967 movie, Bonnie and Clyde, starring Warren Beatty, for a nice portrayal of someone with antisocial personality disorder.

Some of the DSM-5 personality disorders are confined largely to traits within one of the basic domains of personality. For example, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder is largely a disorder of maladaptive conscientiousness, including such traits as workaholism, perfectionism, punctilious, ruminative, and dogged; schizoid personality disorder is confined largely to traits of introversion (e.g., withdrawn, cold, isolated, placid, and anhedonic); borderline personality disorder is largely a disorder of neuroticism, including such traits as emotionally unstable, vulnerable, overwhelmed, rageful, depressive, and self-destructive. Histrionic personality disorder is largely a disorder of maladaptive extraversion, including such traits as attention-seeking, seductiveness, melodramatic emotionality, and strong attachment needs (see the 1951 film adaptation of Tennessee William’s play, Streetcar Named Desire, starring Vivian Leigh, for a nice portrayal of this personality disorder).

It should be noted though that a complete description of each DSM-5 personality disorder would typically include at least some traits from other domains. For example, antisocial personality disorder (or psychopathy) also includes some traits from low neuroticism (e.g., fearlessness and glib charm) and extraversion (e.g., excitement-seeking and assertiveness); borderline includes some traits from antagonism (e.g., manipulative and oppositional) and low conscientiousness (e.g., rash); and histrionic includes some traits from antagonism (e.g., vanity) and low conscientiousness (e.g., impressionistic). Narcissistic personality disorder includes traits from neuroticism (e.g., reactive anger, reactive shame, and need for admiration), extraversion (e.g., exhibitionism and authoritativeness), antagonism (e.g., arrogance, entitlement, and lack of empathy), and conscientiousness (e.g., acclaim-seeking). Schizotypal personality disorder includes traits from neuroticism (e.g., social anxiousness and social discomfort), introversion (e.g., social withdrawal), unconventionality (e.g., odd, eccentric, peculiar, and aberrant ideas), and antagonism (e.g., suspiciousness).

The APA currently conceptualizes personality disorders as qualitatively distinct conditions; distinct from each other and from normal personality functioning. However, included within an appendix to DSM-5 is an alternative view that personality disorders are simply extreme and/or maladaptive variants of normal personality traits, as suggested herein. Nevertheless, many leading personality disorder researchers do not hold this view (e.g., Gunderson, 2010; Hopwood, 2011; Shedler et al., 2010). They suggest that there is something qualitatively unique about persons suffering from a personality disorder, usually understood as a form of pathology in sense of self and interpersonal relatedness that is considered to be distinct from personality traits (APA, 2012; Skodol, 2012). For example, it has been suggested that antisocial personality disorder includes impairments in identity (e.g., egocentrism), self-direction, empathy, and capacity for intimacy, which are said to be different from such traits as arrogance, impulsivity, and callousness (APA, 2012).

Treatment

Personality disorders are relatively unique because they are often “ego-syntonic;” that is, often people with personality disorders are largely comfortable with themselves, with their characteristic manner of behaving, feeling, and relating to others. As a result, people rarely seek treatment for their antisocial, narcissistic, histrionic, paranoid, and/or schizoid personality disorder. People typically lack insight into the maladaptivity of their personality, although eventually people may become aware their personality is dysfunctional through repeated problems in interpersonal interactions, including repeated relationship problems with family and at work.

However, those suffering with moderate to severe diagnoses of borderline personality disorder have a tendency to notice difficulties in psychological and interpersonal functioning. Borderline personality disorder relates to high Neuroticism. Neuroticism is the domain of general personality structure that concerns inherent feelings of emotional pain and suffering, including feelings of distress, anxiety, depression, self-consciousness, helplessness, and vulnerability. Persons who have very high elevations on neuroticism (i.e., persons with borderline personality disorder) experience life as one of pain and suffering, and they will seek treatment to alleviate this severe emotional distress. People with avoidant personality may also seek treatment for their high levels of neuroticism (anxiousness and self-consciousness) and introversion (social isolation). In contrast, narcissistic individuals will rarely seek treatment to reduce their arrogance; paranoid persons rarely seek treatment to reduce their feelings of suspiciousness; and antisocial people rarely (or at least willfully) seek treatment to reduce their disposition for criminality, aggression, and irresponsibility.

Maladaptive personality traits will be evident in many individuals seeking treatment for other mental disorders, such as anxiety, mood, or substance use. Many of the people with a substance use disorder will have antisocial personality traits; many of the people with mood disorder will have borderline personality traits. The prevalence of personality disorders within clinical settings is estimated to be well above 50% (Torgersen, 2012). As many as 60% of inpatients within some clinical settings are diagnosed with borderline personality disorder (APA, 2000). Antisocial personality disorder may be diagnosed in as many as 50% of inmates within a correctional setting (Hare et al., 2012). It is estimated that 10% to 15% of the general population meets criteria for at least one of the 10 DSM-IV-TR personality disorders (Torgersen, 2012), and quite a few more individuals are likely to have maladaptive personality traits not covered by one of the 10 DSM-5 diagnoses.

The presence of a personality disorder will often have an impact on the treatment of other mental disorders, typically inhibiting or impairing responsivity. Antisocial persons will tend to be irresponsible and negligent; borderline persons can form intensely manipulative attachments to their therapists; paranoid patients will be unduly suspicious and accusatory; narcissistic patients can be dismissive and denigrating; and dependent patients can become overly attached to and feel helpless without their therapists.

It is a misnomer, though, to suggest that personality disorders cannot themselves be treated. Personality disorders are among the most difficult of disorders to treat because they involve well-established behaviors that can be integral to a client’s self-image (Millon, 2011). Nevertheless, much has been written on the treatment of personality disorder (e.g., Beck, Freeman, Davis, & Associates, 1990; Gunderson & Gabbard, 2000), and there is empirical support for clinically and socially meaningful changes in response to psychosocial and pharmacologic treatments (Perry & Bond, 2000). The development of an ideal or fully healthy personality structure is unlikely to occur through the course of treatment, but given the considerable social, public health, and personal costs associated with some of the personality disorders, such as the antisocial and borderline, even just moderate adjustments in personality functioning can represent quite significant and meaningful change.

Nevertheless, manualized and/or empirically validated treatment protocols have been developed for only one personality disorder, borderline (APA, 2001). This means that there is a well-researched protocol for how to treat issues with borderline personality disorder. There are many theories and types of treatment for other personality disorders, but treatment protocols are not as specific.

Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder

Dialectical behavior therapy is a form of cognitive-behavior therapy that draws on principles from Zen Buddhism, dialectical philosophy, and behavioral science. The treatment has four components: individual therapy, group skills training, telephone coaching, and a therapist consultation team, and will typically last a full year. As such, it is a relatively expensive form of treatment, but research has indicated that its benefits far outweighs its costs, both financially and socially.

DBT was developed in the late 1980s by Dr. Marsha Linehan and colleagues when they discovered that cognitive behavioral therapy alone did not work as well as expected in patients with borderline personality disorder. Dr. Linehan and her team added techniques and developed a treatment which would meet the unique needs of these patients. DBT is derived from a philosophical process called dialectics. Dialectics is based on the concept that everything is composed of opposites and that change occurs when one opposing force is stronger than the other, or in more academic terms—thesis, antithesis, and synthesis.

More specifically, dialectics makes three basic assumptions:

- All things are interconnected.

- Change is constant and inevitable.

- Opposites can be integrated to form a closer approximation of the truth.

Thus in DBT, the patient and therapist are working to resolve the seeming contradiction between self-acceptance and change in order to bring about positive changes in the patient.

Another technique offered by Linehan and her colleagues was validation. Linehan and her team found that with validation, along with the push for change, patients were more likely to cooperate and less likely to suffer distress at the idea of change. The therapist validates that the person’s actions “make sense” within the context of his personal experiences without necessarily agreeing that they are the best approach to solving the problem.

People undergoing DBT are taught how to effectively change their behavior using four main strategies:

- Mindfulness—focusing on the present (“living in the moment”).

- Distress Tolerance—learning to accept oneself and the current situation. More specifically, people learn how to tolerate or survive crises using these four techniques: distraction, self-soothing, improving the movement, and thinking of pros and cons.

- Interpersonal Effectiveness—how to be assertive in a relationship (for example, expressing needs and saying “no”) but still keeping that relationship positive and healthy.

- Emotion Regulation—recognizing and coping with negative emotions (for example, anger) and reducing one’s emotional vulnerability by increasing positive emotional experiences.

Conclusions

It is evident that all individuals have a personality, as indicated by their characteristic way of thinking, feeling, behaving, and relating to others. For some people, these traits result in a considerable degree of distress and/or impairment, constituting a personality disorder. A considerable body of research has accumulated to help understand the etiology, pathology, and/or treatment for some personality disorders (i.e., antisocial, schizotypal, borderline, dependent, and narcissistic), but not so much for others (e.g., histrionic, schizoid, and paranoid). However, researchers and clinicians are now shifting toward a more dimensional understanding of personality disorders, wherein each is understood as a maladaptive variant of general personality structure, thereby bringing to bear all that is known about general personality functioning to an understanding of these maladaptive variants.

Vocabulary

- Personality Disorder: When personality traits result in significant distress, social impairment, and/or occupational impairment, they are considered to be a personality disorder

- A pervasive pattern of disregard and violation of the rights of others. These behaviors may be aggressive or destructive and may involve breaking laws or rules, deceit or theft.

- Borderline Personality Disorder

- A pervasive pattern of instability of interpersonal relationships, self-image, and affects, and marked impulsivity.

Dialectical behavior therapy is a form of cognitive-behavior therapy that draws on principles from Zen Buddhism, dialectical philosophy, and behavioral science. It started out as a treatment for Borderline Personality disorder but has become a general treatment for self-regulation difficulties.

- Histrionic Personality Disorder

- A pervasive pattern of excessive emotionality and attention seeking.

- Narcissistic Personality Disorder

- A pervasive pattern of grandiosity (in fantasy or behavior), need for admiration, and lack of empathy.

References

- Allik, J. (2005). Personality dimensions across cultures. Journal of Personality Disorders, 19, 212–232.

- American Psychiatric Association (2012). Rationale for the proposed changes to the personality disorders classification in DSM-5. Retrieved from http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevision/Pages/PersonalityDisorders.aspx.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2001). Practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder. Washington, DC: Author.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.) Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association.

- Bateman, A. W., & Fonagy, P. (2012). Mentalization-based treatment of borderline personality disorder. In T. A. Widiger (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of personality disorders (pp. 767–784). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Beck, A. T., Freeman, A., Davis, D., and Associates (1990). Cognitive therapy of personality disorders, (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Bornstein, R. F. (2012). Illuminating a neglected clinical issue: Societal costs of interpersonal dependency and dependent personality disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68, 766–781.

- Caspi, A., Roberts, B. W., & Shiner, R. L. (2005). Personality development: Stability and change. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 453–484.

- DeYoung, C. G., Hirsh, J. B., Shane, M. S., Papademetris, X., Rajeevan, N., & Gray, J. (2010). Testing predictions from personality neuroscience: Brain structure and the Big Five. Psychological Science, 21, 820–828.

- Gunderson, J. G. (2010). Commentary on “Personality traits and the classification of mental disorders: Toward a more complete integration in DSM-5 and an empirical model of psychopathology.” Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 1, 119–122.

- Gunderson, J. G., & Gabbard, G. O. (Eds.), (2000). Psychotherapy for personality disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

- Hare, R. D., Neumann, C. S., & Widiger, T. A. (2012). Psychopathy. In T. A. Widiger (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of personality disorders (pp. 478–504). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Hooley, J. M., Cole, S. H., & Gironde, S. (2012). Borderline personality disorder. In T. A. Widiger (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of personality disorders (pp. 409–436). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Hopwood, C. J. (2011). Personality traits in the DSM-5. Journal of Personality Assessment, 93, 398–405.

- John, O. P., Naumann, L. P., & Soto, C. J. (2008). Paradigm shift to the integrative Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and conceptual issues. In O. P. John, R. R. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality. Theory and research (3rd ed., pp. 114–158). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- John, O. P., Robins, R. W., & Pervin, L. A. (Eds.), (2008). Handbook of personality. Theory and Research (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Livesley, W. J. (2011). Confusion and incoherence in the classification of personality disorder: Commentary on the preliminary proposals for DSM-5. Psychological Injury and Law, 3, 304–313.

- Lynam, D. R., & Widiger, T. A. (2001). Using the five factor model to represent the DSM-IV personality disorders: An expert consensus approach. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110, 401–412.

- Lynch, T. R., & Cuper, P. F. (2012). Dialectical behavior therapy of borderline and other personality disorders. In T. A. Widiger (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of personality disorders (pp. 785–793). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Miller, J. D., Widiger, T. A., & Campbell, W. K. (2010). Narcissistic personality disorder and the DSM-V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119, 640–649.

- Millon, T. (2011). Disorders of personality. Introducing a DSM/ICD spectrum from normal to abnormal (3rd ed.). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

- Mullins-Sweatt; Bernstein; Widiger. Retention or deletion of personality disorder diagnoses for DSM-5: an expert consensus approach. Journal of personality disorders 2012;26(5):689-703.

- Perry, J. C., & Bond, M. (2000). Empirical studies of psychotherapy for personality disorders. In J. Gunderson and G. Gabbard (Eds.), Psychotherapy for personality disorders (pp. 1–31). Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press.

- Roberts, B. W., & DelVecchio, W. F. (2000). The rank-order consistency of personality traits from childhood to old age: A quantitative review of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 3–25.

- Shedler, J., Beck, A., Fonagy, P., Gabbard, G. O., Gunderson, J. G., Kernberg, O., … Westen, D. (2010). Personality disorders in DSM-5. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167, 1027–1028.

- Skodol, A. (2012). Personality disorders in DSM-5. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8, 317–344.

- Smith, G. G., & Zapolski, T. C. B. (2009). Construct validation of personality measures. In J. N. Butcher (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Personality Assessment (pp. 81–98). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Torgerson, S. (2012). Epidemiology. In T. A. Widiger (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of personality disorders (pp. 186–205). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Widiger, T. A. (2009). Neuroticism. In M. R. Leary and R.H. Hoyle (Eds.), Handbook of individual differences in social behavior (pp. 129–146). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Widiger, T. A., & Trull, T. J. (2007). Plate tectonics in the classification of personality disorder: Shifting to a dimensional model. American Psychologist, 62, 71–83.

- Yamagata, S., Suzuki, A., Ando, J., One, Y., Kijima, N., Yoshimura, K., … Jang, K. L. (2006). Is the genetic structure of human personality universal? A cross-cultural twin study from North America, Europe, and Asia. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 987–998.