3 Chapter Three: “I felt like I was hollow inside when it came to holding parts of my culture at heart”: Understanding My Identities as Intersectional

The great majority of authors in this book juggle multiple familial and societal identities and roles. For some, negotiating their multiple identities (e.g., gender, class, immigration status, income, ethnicity, employment status, familial roles) is particularly challenging in spaces not created with them in mind (e.g., work, high school, college). Student author Do’s poem speaks to the intense pressure Do has felt to conform to male gender roles and White expectations of racialized identities. For student authors like Do, negotiating gender and ethnicity (and multiple ethnicities) in a seemingly White America is often complicated—to put it mildly. Moreover, some student authors describe feeling “hollowed” when all their “parts” (Monestime, i.e., their whole self) are not honored as intersectional.

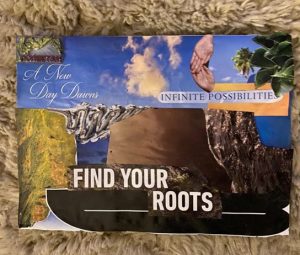

Student authors Monestime and Okamoto found that PSU provided a platform for them to understand and live out their complex racialized identities—and often through caring for younger students, siblings, and friends who were also struggling to find a place of belonging. In addition, student author Safriwe’s collage suggests how she discovered her roots in Central America. In addition, Safriwe—and many of the chapter’s student authors—consider change as not just life’s constant but as a gift itself. Safriwe reminds readers to embrace changes with “open arms”: “I hope for others to also receive change with open arms and learn to embody the shifts that come with time.”

Definition of Terms

Intersectionality. In 1989, African-American scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw coined this term to describe how women—particularly Black women—are simultaneously positioned as women and, for example, as Black, working-class, lesbian, or colonial subjects (1989). In a 2017 online interview for Columbia Law School, Crenshaw further clarified that “intersectionality” is “a lens through which you can see where power comes and collides, where it interlocks and intersects” (2017). However, when I (co-editor Óscar) ask students to define “intersectionality,” they describe how they possess various societal and familial roles and identities, but that the complexity of such interlocking roles is usually rendered invisible in employment and educational settings.

References

Crenshaw, K. W. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, (140):139–67.

Crenshaw, K. W. (2017, June 8). Kimberlé Crenshaw on intersectionality, more than two decades Later. News from Columbia Law. https://www.law.columbia.edu/news/archive/kimberle-crenshaw-intersectionality-more-two-decades-later

Jo Do

In the Flesh

In the man’s hands, cold and the texture is rough

Comfortable for my soul, that has been torn down It

is a familiar pain

I gasp for air between his hold, hoping I can break the surface

But his grip keeps me suffocating like the rest

All I have is the body that carries my soul, a body that does not even belong to me

I feel trapped and a burden, alone in this cave

I want to be perfect, not afraid

I peak of happiness through a window, through the crevices of his grip, it

seems she is miles away

And I long for her touch, her scent

Afraid and still hiding between the fingers, yet visible to the

eye I blend in with the majority and I am still out of place

I am a fraud

I still crave the validation he brings, I am a subject to his drug,

I lost myself in the hold

I want to be happy, independent from the man and his hands

The man’s hands are all I know

“In the Flesh” relates the struggles and corresponding anxiety that come from multiple facets of my identity. As a woman, I have faced misogyny within my family, school systems, and most often internally. As the oldest daughter, I was forced to become the other parent, and with that I became the whipping boy. My mother was a neglectful person, and parent. My role as the oldest meant that all of her shortcomings were a reflection of me rather than herself. I have always felt this pressure to be the perfect daughter and granddaughter. Throughout my growing up, I faced many challenges that made my perfect persona difficult to uphold. When trying to voice how these challenges affected my relationships, familial, social and internal, I was ignored. As I got older, it became harder and harder to express my troubles. This is likely why I struggled to admit to myself and others that I am attracted to women. In school boys would belittle my intelligence and made sexually demeaning comments about me and other girls. The normalization of these comments in conjunction with heteronormative standards made me feel obligated to be with men. Although I knew deep down that I would never feel completely fulfilled in those relationships.

Another element to my anxiety is my racial identity. Though I identify as Hispanic, and White I still find myself not knowing who I am deep down. I have passed as White my entire life and because of that, I’ve never had to worry about day-to-day oppression or fear for my safety. Over time, this has created an overwhelming amount of internal strife, because I have always relied so heavily on being white. This reliance makes me feel like a fraud when claiming my Mexican identity. I hear the uncomfortable “what are you?” being asked more and more frequently, even when it has nothing to do with the conversations I am having. I know it’s meant to be a harmless question, but I feel personally called out. Growing up with the pressure of fitting in, especially as a girl already having to live up to societal standards, I don’t really know my heritage, or who I am. Let alone, how these intersect. When I try to find out, I feel out of place.

When I speak of the familiarity of “man’s hands” I mean it literally. Even though I have accepted being gay, I still hold on to the possibility of also liking men. I have found myself time after time leading guys on, thinking maybe they’ll be the one, but then ending it as soon as it starts to get romantic. This is because I was raised in a heteronormative world where I was expected to fall for a boy or only like boys. So, when it comes to dating, I get very nervous pursuing women I like, because I have all these internal fears and insecurities about how it will go. Since my feelings are only genuine with women, it will be easier to have my heart broken by a woman, but with men, I know I can’t get hurt because the emotions don’t go deeper than it would for a friend. It’s a pattern I’ve only recently acknowledged, and I am doing my best to love the way that I am supposed to love.

Although the elements of my complicated identity have caused some hardships, I am learning to see them as a crucial part of who I am. As much as I would like to ignore the pain that comes from the harsh reality of my identities, that only makes my anxiety worse and leads me to fall back into trying to fit in with what I think everyone else wants me to be. By acknowledging the pain, I can accept and love myself.

Olivia Monestime

Untitled

In my heart sits a special place for the lessons learned, memories made, and revelations I had as a result of being a Peer Mentor for David’s FRINQ class at Portland State University during the 2020-2022 school year. I would have never expected myself to jump into so many academic ventures like I did this past academic year. Now, having time to finally reflect on what happened over the past nine months, I can finally see how my experience at PSU as a whole, as well as the experience of being a Peer Mentor, shaped and guided me.

I grew up in Southern California in the same house my whole life, in a city translated to “Coastal Tableland”–Costa Mesa. The entire county is filled with Spanish and Latino influenced names in the titles of parks, beaches, restaurants, streets, and so on. But, only a small minority of the residences had any actual tie to these lineages and cultures. A lot can be said about this in relation to the lack of cultural diversity I was surrounded by and immersed in growing up. I was often referred to as an ‘oreo,’ or a mulatto. The term is seen as offensive now, but I had to endure a lot of unfiltered speech in the early 2000s. I took on as fact a lot of those identities that others labeled me as. It was true, not very many people looked like me.

My father is a Haitian-born Caribbean man whose family migrated here in exile from a distraught nation ruled by the hands of a dictatorship. Despite the history of my family, it’s rare to see a family member of mine relish in any sort of pity or hardship that may still be endured to this day because of it. My last name, Monestime, can be translated to “My Pride.” This is very suiting and fitting, since pride is the only thing my Dad’s family members take from this history. My mother came from a long-standing generation of Finnish heritage. Scandinavian through-and-through. In contrast to my father’s lineage, my mother had a less tumultuous upbringing, she was never displaced from her homeland against her will. In fact, she decided to venture out of Finland alone, on her own accord. At the age of eighteen, she migrated to the U.S. This isn’t to say she had an easy life, but the strong will of a Finn is regarded highly by me.

The merging of these two cultures resulted in my mixed ancestry. Half of my family lived what seemed like eons away across the globe, while the other half was scattered across the U.S. Although my father had fourteen other siblings, I never had a tight-knit circle of family. My grandparents on both sides all passed on very early, so my connection to the past was only through second-hand narratives. This disconnect with history past one generation of blood kept me from being able to really connect with any of those roots, cultural facets, or traditional stories and myths that Haitians, especially, believe so much in. In a way, I was perceived as a culturally diverse individual, yet I felt like I was hollow inside when it came to holding parts of my culture at heart. Parts of my mental-health-struggles branch from this. Regardless, I yearned to be surrounded by diversity in both race and thought.

When I came to PSU, I was urged more than I’ve ever been to connect to my identity in various forms. Portland’s openness to freedom of expression runs through every part of the people, places, and mindsets that reside here. Which leads me to my experience this past academic year when I became a FRINQ Peer Mentor. I was placed under the theme of Immigration, Migration, and Belonging. On the first day, I knew this was going to be something very special. I was in my third year of college, and most of the students were in their first year, so in a way I got to reflect and relay to them what I wish I would have done differently throughout my first years of college. Many students were from nontraditional backgrounds or were refugees or immigrants, or the children of immigrants. Few of them had not struggled to be here, in this classroom, at a university. It was rare for me to be in a classroom where people of color were the majority. Although this was very new, it immediately felt very comfortable. Conversations with students would often bring me to such a deep place of reflection, through hearing stories of immigration that reflected that of my dad’s family, or struggles with mental health that felt so similar to what I have experienced. I loved learning about their unique lives, and I understood how special it was to be able to connect with each and every one of them in a variety of ways. Each student brought with them such special pieces of themselves. I felt honored that they allowed me to peek into their lives for a year and watch them grow and get out of their comfort zones. And on the other hand, I felt accomplished and proud of myself for my vulnerability with this class and the connections I helped create in my peer mentor sessions, as well as the comfort I offered to the students who needed it.

Going into my final terms of college, I am planning to graduate with a B.S in Biology and Psychology, and a minor in Neuroscience. Connecting more to my identity, through the classes I’ve taken, peers I’ve met, or mentees I’ve mentored, provided me with a deeper appreciation for my accomplishments despite the barriers that often come with being a person of color in higher education. I rarely understand what it’s like to feel any sort of pride for what I’ve accomplished and gotten through due to battles with depression. But through connecting with individuals who embody themselves in their truest selves–those who don’t hide parts of themselves but instead are proud of who they can be–made me finally feel proud of the person I am. The biracial woman that loves her curly hair and brown skin and brown eyes, and sees the beauty in everyone’s uniqueness–especially her own.

Haley Okamoto

Being PI at a PWI

Editors’ note. “PI” stands for “Pacific Islander. “PWI” stands for Primarily White Institution.

As a seventeen-year-old in high school, I based my college decision on a coin flip. It was May 1st, the infamous “National College Decision Day,” and I had a choice to make. I could either stay in my little bubble of comfort and attend college in my home state of Hawaiʻi, or I could take a leap of faith and move to Oregon. I had never been to Oregon, let alone visited the Portland State University campus, but as many first-generation college students do, I looked at pictures online and decided that was good enough! So, as I sat on my bed, coin in hand, I let the universe decide that it was time to pack my things up and move out of state.

Upon arriving at PSU, I truly had no idea what I had gotten myself into. However, bright eyed and bushy tailed, I was excited for this new adventure. I luckily stumbled my way into a program called EMPOWER. It was a retention and student success program for first-generation, low-income, Asian and/or Pacific Islander (API) students, all of which I checked the box for. The community I built through the EMPOWER program is truly what led to me completing my degree at PSU. My peer mentor along with my advisor taught me how to navigate such a large university as an API woman.

I like to think of my time in college as a pond. EMPOWER was the first lily pad I landed on, and after returning to the program during my sophomore year to serve as a mentor, I jumped around to join new programs and take on leadership positions. I dabbled in enrollment work as an Orientation Leader and Student Ambassador giving tours of campus. I had once just browsed through photos of campus, and now I knew everything about it. My work with new students continued through the University Studies Program as a peer mentor. I was entrusted to mentor and teach students through the university’s year-long Freshman Inquiry courses. Very quickly I learned to love the work I was doing with these students and discovered my passion for teaching in higher education. I then dove into the research side of academia after being selected as a McNair scholar. I published my research thesis while exploring the idea of graduate school, though just a few years prior, I had no idea what it meant to have a master’s or doctorate degree. My research in the McNair program focused on multiracial student identities, so everything aligned when I decided to found PSU’s first student organization for mixed-race students. I created Mixed Me at the start of my senior year and became very involved with the campus’s Cultural Resource Centers. The Pacific Islander, Asian, and Asian American Student Center along with the Multicultural Student Center were my home bases because they made me feel safe and accepted. Culture was also embedded into my life when I studied abroad in Spain for my senior capstone. I learned about the connections between my identity and the ways in which Spain utilizes dance, music, and art to portray their historic culture. My personal project depicted the similarities between the Native Hawaiian and Spanish culture. For example, Spain’s flamenco dance and castanets resembles Hawaiʻi’s kahiko hula style and ʻiliʻili implement. Additionally, there were certain regions in Spain that reminded me of Hawaiʻi due to paralleled historic events, native flora, and sense of community. Finally, once I made my way around the pond, I returned to my first lily pad as the lead mentor for the EMPOWER program.

Through all of these experiences, I realized that each program I participated in helped contribute to my development as a first-generation student. As a young Pasifika woman who was raised in Hawai’i, I discovered who I was in this big, brand-new city. It wasn’t until I left my island that I realized how much there was to learn about the world and myself. College gave me the opportunity to embrace all of my identities, and it taught me how to show up in spaces that were not built for me and thrive despite all odds. A lot of first-generation college students do not finish their degree. Even fewer Pacific Islander students do so. My story is a sliver of proof that mentorship, connectivity, and community are all key aspects that can help people like me beat the statistics. I am grateful for the coin I flipped that day; without it, I wouldn’t have grown so much or met the people that have gotten me to where I am today. In 2022, two years after graduating from PSU, I have gone on to pursue my master’s degree in Education through the College Student Services and Administration program at Oregon State University. It is of no surprise to me that after participating in every extracurricular PSU had to offer, I found my passion within student affairs. My career goal is to be in a position that supports the success of Pacific Islander students in higher education through academic, social, and financial means. I hope to be a role model and mentor for Pasifika students by continuing to proudly show up as my full self in any situation in which I find myself.

ʻAʻohe hana nui ke alu ʻia.

No task is too big when done together.

Asia Safriwe

Hope and Community Project

A saying that has brought me great meaning in life has been “the only thing constant in life is change.” Change has always been something that I have had to adapt to throughout my life. I have moved more times than I can count and have had to start over socially in communities that have sometimes been welcoming and in others that have been more hostile towards me. During high school, my mom and I moved to a city that I detested to live with her abusive new boyfriend who was the bane of my existence. In a fog of depression and anxiety, I was outside of the present moment and constantly looking for an escape from my reality. I could not see the bigger picture as I struggled to remember the temporariness of childhood. As I reminisce on a time in which I felt so hopeless, I can now see that it served to teach me valuable lessons about how to navigate tough scenarios and creating necessary boundaries. After high school, I chose to run away from my problems. I worked tirelessly and saved up as much as I could to study in Central America. It was not until I left the city I was forced to conform to and made the most drastic change of my life to move 2,500 miles away into the unknown that I found relief in the changes of life. With the physical distance from my family and the states, I was able to face myself like I was never able to before. My journey traveling was like therapy. I had always hated moving, but with it being my choice this time, I could do so on my own terms.

As my life has gone on, I have come to accept change as a blessing and gotten through a lot by accepting the unpredictable things that life gifts you. I made this collage to represent this new hope and positivity towards change that I have come to value so much. There are various landscapes incorporated because my vast travels inspired me so greatly. I included the words “a new day dawns” as a reminder that things get better, and every day there are “infinite possibilities,” with a chance to make your dreams come true. Sometimes just giving yourself the time to embrace newness can offer a developed insight into the present. Like the one in my collage, the journey to accepting the present was a slippery slope for me, but the final culmination is something more beautiful and inspiring than I could have ever imagined.

Change has brought about a new energy and mentality towards existence, and my embracing it has led me to new heights of myself. I know that even as I now greet change, there will be many more opportunities that may make me stray from this mindset and forget about the gift of change, but this collage is a good reminder to keep my spirits high. I hope for others to also receive change with open arms and learn to embody the shifts that come with time.