Introduction

GOALS OF THE eREADER

The primary goal of this eReader is to showcase stories of hope and transformation written by diverse students enrolled in University Studies courses at Portland State University (PSU), an urban research university located in the heart of Portland, Oregon. The goal is to motivate first-year and transfer students to see that, in higher education, they are not alone in their personal, familial, and academic struggles—and personal, familial, and educational achievements. By also describing moments of joy and transformation in their stories, the student authors reveal that they come to academia with various personal, cultural, and socio-linguistic skills that help them navigate university systems that were not designed with them in mind. The student authors also reflect on overcoming challenges when they lean on hope, their families and communities, and supportive faculty and staff.

We hope that University Studies faculty will assign this eReader in their courses—especially if they are teaching high school college courses (e.g., “High School Senior Inquiry”), first-year courses (e.g., “FRINQ,” “Freshman Inquiry”), and second-year courses (e.g., “SINQ,” Sophomore Inquiry).

Why focus on FRINQ and SINQ students? In our teaching, Óscar and David (the two editors) discovered that FRINQ and SINQ students connect with our student-centered teaching—and our readings and assignments—when students also write some course readings. Therefore, the eReader’s goal is to live up to University Studies’ Vision:

The University Studies Vision: Challenging us to think holistically, care deeply, and engage courageously in imagining and co-creating a just world. (University Studies, n.d.)

By creating an electronic platform (i.e., an eReader), our student authors challenge their student peers—and faculty—to think holistically about who they are in classroom spaces. Indeed, we (Óscar and David) often find that students learn as much from each other as they do from us or the assigned texts. We believe in Paulo Freire’s world vision that “for individuals to transform the world—and later the word (e.g., policies, structures, practices)—, they must first be conscious of what they see, work to transform it, and continuously re-examine their perspectives (Fernández et al. 2023). Freire, for example, writes:

Reading the world always precedes reading the word, and reading the word implies continually reading the world. [. . .] In a way, however, we can go further and say that reading the word is not preceded merely by reading the world but by a certain form of writing it or rewriting it, that is, of transforming it through conscious, practical work. For me, this dynamic movement is central to the literacy process. (1987, p. 35)

Finally, the eReader aims to help student authors directly in their writing and life goals. By submitting their stories to us, student authors will experience an editing process that encourages them to write more clearly, especially as they gain confidence in the power of their writing and life experiences. As editors, Óscar and David edit their writing carefully and positively to make it clear and authentic. Finally, student co-authors may add this eReader entry as an accomplishment in their resumes. We hope such an accomplishment can “put them on top” when they seek scholarships, apply for graduate school, and advance their careers.

A final goal is to showcase writing by all students in University Studies, including juniors and seniors taking junior cluster courses and Capstone courses. With time, we hope that this eReader reader will capture stories of hope and transformation by students from all levels of the University Studies Program—from high school students taking SRINQ (“Senior Inquiry,” a University Studies college course enrolling area high school seniors) to sophomores, and juniors and seniors taking Capstone courses.

HISTORY OF THE eREADER

This eReader was inspired by stories from diverse, minoritized students, including undocumented and immigrant students (i.e., first and second-generation immigrants). Such students are enrolled in University Studies’ Immigration, Migration, and Belonging FRINQs. For over seven years (2016-present), Óscar and David have been the lead educators teaching this immigration-themed FRINQ course.

2015: Immigration, Migration, and Belong FRINQ’s origin story. During the fall term of 2015, University Studies faculty and staff met to discuss Óscar’s idea to propose a new FRINQ course that would impact our institution’s growing population of immigrant students. This idea originated as part of his participation in PSU’s Refugee and Immigrant Student Issues Committee—and the committee’s efforts to support this student population and its allies. Dr. Yves Labissiere (then-interim Director, University Studies) attended the first two meetings and suggested inviting Dr. Alex Stepick (PSU, Sociology), a committed and published expert in immigration studies. The exploratory committee was formed later that fall of 2015 with the following members: Mirela Blekic (then-retention Associate, University Studies), Annie Knepler (Writing Coordinator, University Studies), Alex Stepick (Sociology), and Óscar Fernández (Comparative Literature, and then-Adj. Asst. Prof. for FRINQ’s “Race and Social Justice” course). Blekic, Knepler, Stepick, and Fernández continued to meet monthly during the 2014-2015 academic year. Although the three faculty members came from different disciplines (i.e., Sociology, Comparative Literature, Writing Across the Curriculum), we created an overarching assignment that easily suits and is adaptable to various academic approaches: We came up with the concept of having students examine not only their IMB (immigration, migration, and belonging) story but also a peer’s. Many of the stories in this eReader reader result from this IMB assignment.

2022: David’s Blog. During the winter of 2022, Óscar discovered David’s blog, “Transformations: Stories of Service and Hope” (Peterson del Mar 2023). In it, David shares stories of hope and transformation with his Immigration FRINQ students. Óscar met with David that winter term 2022 to ask him the following “what if” questions:

- What if we combine stories of hope and transformation from our Immigration FRINQ courses in one eReader?

- What if we motivate student authors to write more by asking them to participate in a publication-like editing process?

- What if we create a free eReader that University Studies faculty may assign in their courses?

- What if we create an eReader that describes, in a story-telling mode, how PSU impacts the lives of our students?

- What if student authors bolster their career prospects by adding to the resumes that they are published eReader contributors?

This eReader is the answer to those five “what if” questions. Additionally, for Óscar, this eReader also represents a bookend in his academic career as a queer immigrant scholar from Costa Rica. What started in 2015 as a dream (i.e., to create and teach an immigration-focused FRINQ course) is now, in 2024, a free eReader that documents stories of hope and transformation by diverse PSU students.

DEFINITIONS OF TERMS

In this eReader, student authors and co-editors use PSU-specific terms, such as “FRINQ,” “peer mentors,” and “University Studies.” Moreover—and given that this eReader is accessible to global audiences with Internet access—we define terms that may be specific to U.S. cultures in and outside academe—for example, “DACA,” “Latinx,” or “QTBIPOC.”

DACA. “DACA” refers to a US immigration program called Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (Department of Homeland Security, 2020). The DACA program shields “some young undocumented immigrants —who often arrived at a very young age in circumstances beyond their control—from deportation” (Anti-Defamation League, 2020, para. 1).

DREAMERS. “DREAMers” refers to the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors Act (“DREAM”), a failed 2001 immigration bill in the U.S. Congress. Generally, “DREAMers” is a U.S.-specific umbrella term used to designate students who may identify as undocumented, DACA-mented, or un-DACA-mented (Anti-Defamation League, 2020, para. 1)

FRINQ. “FRINQ” refers to Freshman Inquiry, a 15-credit, interdisciplinary, yearlong course for incoming first-year PSU students. FRINQ has a main section with a professor and a Mentor Inquiry section with a peer mentor, an advanced student trained to help first-year students navigate university courses and services, .e.g., Writing Center, the Learning Center, Financial Wellness Center, Multicultural Centers, Student Health Center (University Studies, n.d.).

Senior Inquiry. “High School Senior Inquiry” refers to PSU’s Freshman Inquiry courses adapted for the high school context. Senior Inquiry currently serves approximately 510 students in 6 schools across 4 districts in Portland, Oregon, and adjacent school districts (University Studies, n.d.)

Imposter syndrome. “Imposter syndrome”— or “imposter phenomenon” as originally called by Clance & Imes—is defined as: The psychological experience of believing that one’s accomplishments came about not through genuine ability, but as a result of having been lucky, having worked harder than others, or having manipulated other people’s impressions, has been labeled the impostor phenomenon. (Clance & Imes, 1978)

Alternatively, the co-editors define “writing-related imposter syndrome” as moments when writers—particularly students of color and diverse first-generation students—doubt their writing skills because they internalize fears that their writing will expose them as frauds in academia.

Latinx/ Latiné/Latino(a)/Hispanic and “Chicana/o/x. “Latinx” is a gender-neutral, nonbinary alternative to Latino or Latina and describes persons who are of or relate to Latin American origin or descent (Noe-Bustamante, 2020 para. 2). Student authors who self-identify as “Hispanic” may use alternative designations, such as “Latino, Latina, or Latiné.” “Latiné” is another term gaining traction and spurring debate (Colorado State University’s El Centro, 2024). In addition, some student co-authors self-identify as “Chicana, Chicano, or Chicanx.” “Chicana/o/x” refers to Mexican-Americans born in the United States who also identify with their indigenous ancestors; however, not all Mexican-Americans necessarily self-identify as “Chicana/o/x.” In the 1970s, Ruben Salazar, then-writer for the LA Times, famously defined the term—albeit the androcentrism in his definition—as “A Chicano is a Mexican-American with a non-Anglo image of himself” (1970). For this eReader, each Latinx student author will use the terms that best suit them. For example, co-editor Óscar—a queer immigrant scholar from Costa Rica—uses “Latinx” as his self-identifying term.

Peer mentors in University Studies’ Peer Mentoring Program. The Peer Mentor Program at PSU is the “largest mentoring program on campus and in the State, drawing from a range of disciplines, colleges, and majors to support the interdisciplinary nature of Freshmen Inquiry (FRINQ) and Sophomore Inquiry (SINQ) courses. [ . . . ] Twenty years since its inception, the program still serves as one of the nation’s largest curricular peer-mentoring programs in general education” (Fernández et al., 2019).

People of color. “POC or people of color” refers to persons of color. BIPOC refers to Black, Indigenous persons of color (Garcia, 2020, para. 2).

QT/BIPOC. “QTPOC” is defined as individuals who self-identify as queer, trans persons of color (Darling-Hammond, 2019). The student authors may self-identify using diverse, intersectional terms. Therefore, we are using “QT/BIPOC” (queer, trans, Black Indigenous persons of color) as an umbrella term.

Student-centered teaching. “Student-centered teaching,” also known as “learner-centered teaching,” refers to a teaching philosophy that shifts the instructional focus from the educator to the student, including active learning, cooperative learning, and inductive learning (Felder, 2016).

The Senior Capstone Program. Capstone courses “are designed by PSU’s faculty as community-based learning experiences that engage students in dynamic projects throughout the Portland metropolitan region and beyond” (University Studies, n.d.) According to its director, Dr. Seanna Kerrigan, Capstone courses aim “to prepare graduates for employment and community activism. By actively engaging interdisciplinary teams of students in the community to address genuine community needs, Capstones help address the explicit learning goals of our general education program: “communication,” “ethics and social responsibility,” “inquiry and critical thinking,” and “diversity, equity, and social justice” (formerly called “the appreciation of the diversity of the human experience”). (Fernández et al., 2019).

SINQ. “SINQ” refers to Sophomore Inquiry, an interdisciplinary course for second-year and transfer students. SINQ has a main section with a professor and a Mentor Inquiry section with a peer mentor, an advanced student trained to help students navigate university courses and services. SINQ is “an opportunity to explore topics of interest that differ from, yet complementary to, your major” (University Studies, n.d.).

University Studies. “University Studies” refers to PSU’s general studies program (established in 1993), including Freshman (FRINQ), Sophomore (SINQ), and Senior Capstone courses built on four learning goals (Hamington & Ramaley, 2019).

eREADER’S VALUES AND PHILOSOPHY

Challenging Individualism in Publications: High School and First-Year Students as Student Authors (DAVID)

In the traditional approach to being an academic, professors seldom co-publish with first-year students. In fact, there are powerful reasons or incentives to avoid such students altogether, as working with upper-level or graduate students is considered both more interesting and less work, as more advanced students tend to be more skilled and independent. Professors most commonly collaborate with graduate students, especially those they advise in some capacity, as such students eventually engage in sustained original research and are very invested in publishing in their fields. Professors benefit from co-authoring with such students not simply by enhancing their reputation as capable advisors but also by being able to be the leading authors in papers, articles, book chapters, or books for which their students do the majority of research and writing.

I (David) did not pursue co-publishing with students until a quarter century after becoming an academic, as part of an Honors College class at PSU that involved volunteering with English Language Development students at Reynolds High School in 2017. These students had been in the U.S. learning English for a few months or years and were reading and writing English far below their age level. Their remarkable teacher, Debra Tavares, understood that the opportunity to write about their lives might provide both a powerful incentive to write and help their psycho-social development.

That writing process was often fitful. I (David) well remember the afternoon that three young women, all of whom had expressed great enthusiasm for the project, sat silently at their desks, staring at something in the distant past. When approached, all three remarked that their lives had been full of sadness. They did not know where to start writing about their lives or even if they wanted to start at all.

My first impulse as a highly educated white outsider was to marshall resources (e.g., financial aid office, counseling office) to address or “fix” this “problem.” I approached the lone school counselor charged with assisting traumatized students. She was sympathetic but already stretched beyond her limit with more conventional student traumas. I contacted a local organization devoted to serving immigrants, and one of their specialists urged me to write a grant for and oversee a culturally responsive group therapy program for these students, a worthy but daunting project that I had neither the training nor the time to undertake. A third person I approached had a much more helpful response. Ishmael Beah, author of A Long Way Gone (2008), the widely-read memoir of his years as a child soldier in West Africa, had a simple answer to what these students most needed. He remarked that given sufficient time and space, these students would, when they were ready, take three steps—steps that he had himself taken for many years. First, they would tell their stories to themselves. Then they would tell them to one other person. Finally, they would tell them to the world.

And that’s more or less how our classroom project unfolded. All three of the young women verbally shared elements of their stories, and some of those stories were profoundly sad. Only one chose to write about her losses in any detail, and she did so with deep eloquence and feeling. Óscar and Dr. Staci Martin (PSU, School of Social Work) have written about the temptations and dangers of trauma tourism (Fernández et al., 2022). I certainly learned the importance of constantly bearing in mind how easily I might coerce and harm these young women and how easily (especially) white people in authority can extract testimony or life stories that much more vulnerable young adults do not really want to share.

In taking these lessons from this high school classroom to working with my Freshman Inquiry students, many of whom have also experienced substantial trauma, I (David) have tried to provide them with many ways to talk and write about their lives and to make careful, informed choices about what they will share and to what degree they will make it public. Students share elements of their lives several times weekly, in class, and weekly reflections. I meet with them privately several times a year, and they often choose to write about their experiences in formal essays. Some over the years have published their experiences in my blog, in co-authored articles, or as part of a book chapter (Aguilar Becerra et al., 2021; Martin et al., 2022; Peterson del Mar et al., 2022; Students from Immigration, Migration, and Belonging et al., 2023). Some in their weekly reflections share in great detail about repairing their cars, the prospects of their favorite soccer team, or a film or friend they have recently enjoyed. Some write about the deaths of loved ones. Some wonder if they will ever feel safe. As Beah predicted, they constantly make their own choices. One of my favorite memories as a teacher is of a day when I (David) expected several students to show up to share stories with each other, and only one did. He remarked that he wanted at least one person at Portland State University to know what growing up in a refugee camp was like, and he proceeded to spend most of an hour telling me about that. I did not know if that story would ever be shared with the world, and it is not my story to share. But it was one of the most meaningful and impactful hours I have spent as a professor listening to that remarkable young man.

These collaborations require re-learning how to be a professor, as it usually entails the opposite of professing, of performing the role of “the smartest person in the room.” I am trying to replace that hard-earned and intimidating persona with a demeanor of kindness and non-intrusive curiosity, a deep interest in and respect for each student, including their experiences and how they wish to share them.

Academic Publishing and Elitism

Our frequent use of words such as “community,” “collaboration,” and “social justice” notwithstanding, academia is a fiercely competitive and, therefore, an individualistic profession in which graduate students and professors quickly learn that the quickest route to job security and professional status is to publish as much as possible in the most prestigious journals and presses that one can manage to. The capacity to win grants is also very important in the so-called hard sciences. Still, most academics, particularly those at research universities, are rewarded primarily based on their publications.

Scholarly productivity is most easily measured simply by counting, but publications must meet a certain standard in order to be counted, namely that they appear in peer-reviewed publications. Peer review is a process in which editors enlist academics considered authorities in the manuscript’s field to judge its quality and whether it should be accepted essentially as is, accepted only if substantial and sufficient revisions are made, or if it will be rejected outright. These referees are ordinarily asked to comment on various topics, from the clarity of prose to the clarity of arguments to the quality of the author’s research and sources. Still, the key consideration is whether or not the manuscript makes a significant and original contribution to the field. In other words, the article, book chapter, or book should break some new scholarly ground and should at least in some small way increase the body of scholarly knowledge in its particular field or fields.

However, not all journals and book publishers are considered equal. Some are more widely read, or at least considered much more prestigious, than others. Some journals, in fact, publish their acceptance rate, and of course, the more prestigious the journal, the lower the acceptance rate is liable to be. To the general public, a book may be a book. Still, there is an intricate and widely accepted pecking order in academia, even among peer-reviewed presses. The difference between being published by or having a book contract with, say, Oxford University Press and a much less respected press could be the difference between getting an academic job or not, getting a tenure-stream academic job or not, being tenured or losing your job, or being promoted to a higher pay grade.

From entering graduate school until they are promoted to Full Professor, academics have a strong financial and professional interest in publishing as much as possible, preferably in the right (most exclusive) places. As that period of establishing oneself commonly takes at least two decades, academics, therefore, undergo a very powerful process of professional selection and socialization designed to reward those who reserve as much time as possible for publishing as much as possible and in the best places possible.

This system of professional socialization and advancement has obvious and very negative consequences for any sustained interaction with undergraduate students, let alone with co-publishing with them. Faculty at research universities are essentially trained to and rewarded for putting research ahead of teaching. As Jonathan Zimmerman puts it in The Amateur Hour: A History of College Teaching in America (2020), professors have commonly “described research as their ‘work’ and teaching as their ‘load,’” an irksome duty to be minimized so that one can get on with the more rewarding work of publishing (p. 232).

Any scholarly collaboration is time-consuming, as time must be spent discussing and agreeing on what to research, how to organize and divide the work, and, of course, aligning the writing so that the parts fit together well. These difficulties are compounded when the co-authors are beginning college students; as such, students are commonly struggling to adjust to college and writing at a college level. Very few have much, if any, experience as academic researchers. Hence, faculty collaborating with first-year undergraduate students must set aside a substantial amount of time to encourage and train them and often edit their work.

Moreover, the results of these collaborations are seldom considered serious or actual scholarship. Indeed, to the extent that first-year students are writing original work, it is likely to be their life stories, the sort of writing that academics are apt to dismiss as “anecdotal” or “personal,” even if this work is much more influential than (often very narrow) scholarship that may be read by a dozen people or less, and even if this work sheds considerable light on the lives of underrepresented students and, therefore, has the capacity to change the ways that colleges go about educating such people.

Julia Lee, an English professor, shares in Biting the Hand: Growing Up Asian in Black and White America (2023) that her teaching “changed when my classroom became more ‘diverse’ and ‘nontraditional’” (p. 174). Working in spaces “where people of color were in the majority” prompted her to realize that “I had perfected a teaching persona that was based on my experiences in elite white spaces,” an aura “of invulnerability” ill-suited for classes full of students with low incomes and daunting responsibilities, people who had survived racism and poverty and “were curious and eager and idealistic and humble” (pp. 174-175). Listening to our students can change how academics define what–or whom–should be at the center of our work and how our research and writing projects might incorporate their insights and experiences.

USING THE eREADER IF YOU ARE A STUDENT

Some of the stories here may resonate with you; others may not. The eReader’s chapters are thematic; therefore, first read those chapters with themes that resonate with you. However, we hope you read the entire book! We gathered these stories of hope and transformation so that you realize that—in your accomplishments, your joy, and your struggles—you are not alone. Although this eReader is not a self-help book (e.g., it does not identify specific ways to overcome financial, mental, and race-based barriers), we hope you find the stories inspiring enough so you reflect on your personal barriers while celebrating your community’s accomplishments and joys. Additionally, we gathered stories of hope by student authors to disrupt the “inner critic” that brings us down. We all know the inner critic’s script running in our heads:

- You are not good enough.

- You don’t belong here.

- You are alone.

- People (at work and school) know you are a fraud.

- You will never accomplish your dreams.

In short, “inner critic” describes the strong inner normative voice with which some people block themselves.” (Stinckens et al., 2002).

If you have a story of hope and transformation to share with us, contact the co-editors. Before you do, though, read the FAQ for Students, which appears at the end of this Introduction.

Finally, as you finish each story, set aside five to ten minutes for reflective journaling. Reflective journaling is one way for you to counteract your “inner critic” and to bring to your awareness your stories of hope and transformation. In your composition book, your legal pad, and your screen, answer any or all of these questions (Vogt et al., 2003; all changes are ours):

- What’s taking shape as you read these stories?

- What are you hearing underneath the variety of stories of hope being expressed?

- What new connections are you making?

- If there was one thing that hasn’t yet been addressed in this eReader to reach a deeper level of understanding/clarity, what would that be?

USING THE eREADER IF YOU ARE AN EDUCATOR

Suppose you are an educator (e.g., a high school, college, or university educator). In that case, we encourage you to assign this eReader as part of your student-centered teaching approach, e.g., students help educators select course-specific reading, assignments, and even grading criteria. For example, students and educators may decide that some assignments could be self-graded by using a self-grading rubric (Felder, 2016). Below, please find two types of teaching approaches to adopt—and adapt according to your learning goals—regarding this eReader.

Set classroom time aside to write by using self-reflection prompts. Start each class (e.g., each “period” or “lecture”) by asking students to practice reflective journaling around. Why? We have found that if our students get into the habit of writing each day during class, that habit minimizes some of the negative attitudes students self-disclose about their writing process. In our teaching experience, setting time aside for students to write with guiding prompts meets three writing-related goals:

- Builds students’ confidence in their writing;

- minimizes perfectionism (i.e., when writers “freeze” because they expect each sentence they write to be “perfect”); and

- reduces writing-related imposter syndrome

In addition to the appreciative inquiry questions we shared with students just above (see “Using this eReader if you are a Student”), here are deeper writing prompts to share. We encourage you to explain each prompt further. Finally, because the prompts below may reveal deeper emotional and intellectual insights, we encourage educators to allow students to share their aha! moments in pair shares, small groups, or large group discussions (Vogt et al., 2003; all changes are ours):

Appreciative Inquiry Prompts

- What assumptions do we need to test or challenge here in thinking in (specific chapter or story)?

- What would someone who had a very different set of beliefs than we do say about (your specific situation)?

- What’s possible here and who cares? (Rather than “What’s wrong here and who’s to blame?”)

- How can we (faculty, peer mentors, students) support each other in taking the next steps? What specific contribution can we each make?

- What seed might we plant together today that could make the most difference to the future of (your situation)?

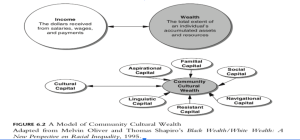

Minimize students’ negative self-perceptions. In-class discussions about students’ self-perception of their writing, including their takeaways after reading the eReader’s stories of hope, minimize narratives that diverse students—particularly students of color—are “broken.” If educators find themselves—and their students—dwelling on students’ deficit, challenge all learners to think that students of color are not broken—rather, systems (e.g., political, legal, education), practices (e.g., how we teach and what we teach), and policies (e.g., rules and regulations) are surely broken (Students of color aren’t broken, 2020). Share with students that a deficit mindset (i.e., students of color are a deficit in higher education) has long-term harmful consequences: “Many students of color and students from low-income backgrounds are seen as “broken” or in need of “fixing,” which undermines their excellence and results in real and harmful consequences” (Students of color aren’t broken, 2020). To minimize the narrative that diverse students are “broken”—narrative that some educators and students themselves carry—the co-editors discuss Yosso’s community cultural asset model with students. Yosso’s community cultural wealth mindset, instead, asks educators—and students—to recognize that despite many real barriers diverse students face (e.g., wealth disparities, immigration-related fears if one is undocumented, first-generation students’ imposter syndrome), such students do possess skills to navigate systems that were not designed with them in mind. Yosso defines “community cultural wealth” as

. . . the array of cultural knowledge, skills, abilities and contacts possessed by socially marginalized groups that often go unrecognized and unacknowledged. Various forms of capital nurtured through cultural wealth include aspirational, navigational, social, linguistic, familial and resistant capital. These forms of capital draw on the knowledges Students of Color bring with them from their homes and communities into the Classroom (2005, p. 69).

Below, please find a helpful diagram you can share with your students (Yosso, 2005/2017, p. 122):

After sharing and discussing Yosso’s model with students, we ask them to answer the questions below during their reflective journaling. We found that asking students to complete all six prompts in one sitting was overwhelming. Instead, we devote one week to each prompt below. Figure 2’s prompts below are based on Yosso’s “community cultural wealth” model (Yosso, 2005/2017; all changes are ours):

Sample reflective journaling questions based on Yosso’s community cultural wealth (all changes are ours).

| 1. Aspirational capital |

2. Linguistic capital |

3. Familiar capital |

4. Social capital |

5. Navigational capital |

6. Resistant capital |

| Describe experiences where, despite barriers, you maintained “hopes and dreams for the future” (Yosso, p. 123) | Describe experiences you attained by the languages you possess and/or style of communication (including storytelling, visual art, music, or poetry) | Describe experiences you attained thanks to your familias, kinships, extended families, and created families. What lessons of care, coping, and providing inform your consciousness? | Describe experiences where “networks of people and community resources” (p. 124) supported you (emotional, financial)? | Describe strategies when navigating institutions not created with Communities of Color in mind. | Describe sets of knowledge and skills you’ve had through “oppositional behavior” that challenges inequality. Describe events or behaviors where you challenged the status quo. |

Why share Yosso’s model with all students? The purpose of discussing Yosso’s model with students is three-fold. First, diverse students begin to recognize that they bring to classroom spaces a great deal of knowledge and skills from their families and cultures (what Yosso terms “capital”). Second, by sharing such a community cultural wealth model, faculty signal students that their cultures are an asset in classroom spaces. Finally, by answering the six prompts above, the co-editors find that students themselves begin to write narratives that disrupt narratives that they are “broken” and are “imposters” or “frauds.”

Why share Yosso’s model with specific students (i.e., students that faculty see as terrific student author contributors for this eReader)? If you are an educator recommending students to this eReader project, explore Yosso’s model with them as you edit their work. In our experience, student authors of first drafts often describe themselves as “broken” (e.g., as lacking skills or a story worthy to be shared). As you work with them in their eReader submissions, ask them to complete Yosso’s six prompts. Discuss with them how completing the six prompts may generate new ideas to include in their stories of hope and transformation.

Minimizing trauma tourism in student’s writing (and notions of self). When I (Óscar) ask students—particularly students of color—to write about their lives, many only center their writing about their barriers. Some cannot see their strength or individual and communal wealth. This perspective is exacerbated in higher education when students are asked to “traffic” their stories of trauma for need-based scholarships and diversity workshops. As discussed elsewhere with student co-authors, “trauma tourism” is a way students of color partly pay for their schooling; we defined “trauma tourism” as “moments when university audiences (‘tourists’ in this case) ask students to remember, share, and write about traumatic events to support learning in diversity workshops, apply for monetary scholarships, and move audiences to social causes” (Fernández et al., 2022, p. 121). In writing workshops, I share with my students that while such experiences must be named and recognized as harmful, sharing stories that demonstrate their personal and communal cultural wealth is also important. I hope that this eReader gives readers a holistic sense of student experiences.

Finally, if you have students in mind who would be terrific student authors for this eReader, please read the two FAQs at the end of this Introduction. The two FAQs will answer questions about the submission process, the faculty member’s role, and—most importantly—the rights and responsibilities of student authors.

CO-EDITOR BIOS

Dr. Óscar Fernández (University Studies, Assistant Professor of Teaching) works at Portland State University and served as University Studies’ inaugural Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Coordinator (2017-2020). He teaches a yearlong Immigration, Migration, and Belonging FRINQ (Freshman Inquiry) and Sophomore Inquiry courses on social determinants of health, and popular culture. He specializes in inter-American studies, literary theory, and the intersection of culture, sexuality, and representations of disease in Iberoamerican literature. Additionally, he examines experiences by contingent faculty and QT/BIPOC (Queer, Trans, Black, Indigenous, People of Color) students in the academe. He holds an external grant for the 2020 Residential Research Group Fellowship from the University of California Humanities Research Institute, “Disciplining Diversity,” in the fall of 2020, University of California, Irvine. In 2020, he received PSU’s 2019-2020 President’s Diversity Distinguished Faculty Award. From 2020-2024, he organized and co-chaired an ad hoc committee, PSU/HSI Exploratory Committee (HSI—Hispanic Serving Institution), to gather recommendations and aspirations regarding PSU becoming an urban Hispanic Serving/Thriving Institution. His published work appears in Comparative Literature Studies, Oregon Literary Review, the Journal of General Education: A Curricular Commons of the Humanities and Sciences, Textbook & Academic Authors Association’s book—Guide to Making Time to Write—, PMLA (Publications of the Modern Language Association), and Routledge’s Global South Scholars in the Western Academy. He earned a Ph.D. in Comparative Literature from The Pennsylvania State University.

Dr. David Peterson del Mar, Professor, University Studies and History, PSU. The author of seven books on topics ranging from the history of interpersonal violence to U.S. views of Africa, he spends most of his time with present and past students of Freshman Inquiry courses, and most of his recent research has been in collaboration with those students, particularly around how public universities might be more student-focused. In 2012, he co-founded, with a high school student, Yo Ghana, a 501(c)(3) organization devoted to linking youth in Ghana and the Pacific Northwest so that they can learn about and inspire each other.

FEEDBACK TO THE CO-EDITORS

We hope to edit this book every few years—and during the summer months. We want feedback from students and faculty. Let us know what stories you would like to share with us. Feel free to point out corrections (e.g., syntax, spelling). If you are a student, share which eReader stories were meaningful to you and why. If you are an educator, share how you use this eReader reader in your courses.

FOR STUDENTS: FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS (FAQ)

If you are a student interested in submitting work, please read the FAQ for Students below.

If you are a faculty member with students in mind who would be terrific student authors, please read the FAQ for Educators below.

FAQs FOR STUDENTS: 15 QUESTIONS

Theme and submission length

- What is the theme of this eReader?

-

- Submit stories with the theme of hope and transformation.

- Indeed, this theme is open-ended. We advise reading the eReader’s stories to get a “feel” for the eReader’s theme.

- We reject “stories” that are academic essays. For example, if you submit an essay arguing X,Y, and Z in Cien años de soledad by Gabriel Garcâ Máquez, we will likely reject your submission.

- However, we will consider your submission if it describes how a book, a poem, a song (or any other art form) changed your life.

- I see that many of the eReader stories are primarily text-based. May I submit work in other formats (e.g., video essays, poems, art pieces with an artist’s statement attached)?

-

- Yes!

- Reach out to us with your ideas for alternative formats and multimedia.

- However, Óscar and David are limited by the eReader platform’s online policies.

- How long should the essays be?

-

- About 2,000 words max.

- If I reference outside sources (e.g., books, chapters), do I have to cite them?

-

- Yes!

- You may cite using MLA (Modern Language Association) or APA (American Psychological Association).

- Provide a perfect citation page! PSU’s Writing Center and Purdue University’s OWL page provide online tutorials.

- PSU’s Writing Center provides one-on-one tutorials.

- May I share brainstorms or the first pass of my story with Óscar and David?

-

- No! (Unless you are a student in their class.)

- Please share with us the work that you have polished with the assistance of your peers, your professors, and Writing Center coaches.

Assignment grades

- Does submitting my work count as a graded assignment or extra credit in my courses?

-

- No!

- Óscar and David’s role is working with you as writing coaches.

- Although we may be your professors, we are your writing coach.

- We do not grade your submissions.

Privacy, process, and deadlines

- What’s my expectation of privacy when my story is published via an eReader?

-

- The eReader’s audience is anyone around the world with online access.

- Therefore, if your story may harm you (e.g., your reputation, your employment), do not submit work.

- May I submit work anonymously?

-

- Yes, but reach out to us because Óscar and David must know your name and your PSU identification number. This eReader is only for PSU students.

- Anonymous authors must still complete a consent form.

- Óscar, David, and PSU’s Millar Library staff will know who you are. However, we won’t publish your name in the eReader.

- May I take it down if I change my mind after my work is published?

-

- Yes!

- Contact Óscar and David as soon as possible.

- However, give us about six months to delete your entry.

- We won’t ask you why you decided to take down your entry.

- What paperwork do I have to complete?

-

- To PSU eReader-related policies, all students must complete a consent form to participate.

- We cannot publish your work if students do not complete a consent form.

- Reach out to us: We will share our specific electronic consent form.

- What else must I do if I sign the consent form and submit my story?

-

- We will reach out to you with a soft and hard deadline to submit edits.

- We share edits directly with you via Google Docs.

- Need a tutorial on how to share and edit using Google Docs? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R7SKHZCyTUc

- About “soft deadlines.” After we edit your work, we generally give students about 1-2 months to review our edits.

- About “hard deadlines.” After the soft deadline, we provide student authors with a final hard deadline to review our edits.

- Are you missing all the deadlines? If you miss the hard deadline and we haven’t heard from you about your situation, we won’t be able to accept your submission.

- Can I include this as a “real” publication in my resume?

-

- This will probably not count as a peer-reviewed academic publication, the type that graduate students and professors commonly use to get jobs as professors and promoted at universities.

- However, this eReader publication will look good on applications for graduate school and various employment opportunities.

- Why should beginning college students be sharing their experiences? Aren’t we here to learn?

-

- Most PSU students, and certainly those from under-represented communities, bring a wealth of experience to PSU, and many believe that their struggles might make them unfit and unprepared for college.

- We have noticed that when our students share their stories of struggle and resilience, many other students recognize elements of their own lives and stories and feel less alone and more like they “belong” at PSU.

- So, your stories can be a source of encouragement for many others.

Peer Mentors in University Studies’ Peer Mentoring Program

- What if I am a peer mentor in University Studies? May I submit a story?

-

- Yes!

- Read the FAQ for Students.

- In the future, we would love to have a book chapter devoted to stories of hope and transformation authored only by peer mentors in FRINQs and SINQs.

Financial compensation

- I see that this is an eReader. Do I get royalties (e.g., $) as a published eReader contributor?

-

- No!

- This eReader reader is accessible to anyone online.

- Co-editors Óscar and David do not receive any eReader royalties.

FAQs FOR FACULTY: 6 QUESTIONS

Primary educator’s role

- I have a promising student whose story should be in this eReader. What are my actions?

-

- Share the eReader’s FAQ for Students.

- Ask the students if they want to participate in this project, which is unrelated to their courses or grades.

- It is up to the student to reach out to Óscar and David.

- Remind students to complete a consent form that Óscar and David will share with them.

- Edit the student’s story for grammar and syntax for publication before they submit the work to us.

- If you have already graded the student’s story, edit it one more time before your student submits it to us.

- Although Óscar and David will edit submissions once more, we want faculty to be the first “writing coaches.”

Number of submissions to send

- May I submit dozens of assignments if my course assignment is centered on storytelling?

-

- No!

- Óscar and David treat each student as an author, sending individual manuscripts to eReader editors. Therefore, students must consent to participate and write more outside their assigned course.

- This eReader project is not an archive of course assignments in University Studies.

- Identify who wrote a compelling story. We won’t define “compelling” to faculty, so meet with us if you have questions. Talk to each student and ask them if they want to participate.

- Óscar and David will update this book every few years and only during summer.

- Due to bandwidth limitations, we may accept 1-10 submissions per year, provided that the primary educator already edited the work with the student.

ePortfolios

- May I submit students’ University Studies ePortfolios with story-telling components?

-

- No!

- Óscar and David are looking for stand-alone stories.

- This eReader project is not connected to University Studies’ yearly assessment of our FRINQ ePortfolios.

- However, if your student’s ePortfolio features a compelling story, talk to them. Ask them if they want to participate in this eReader and create a standalone ePortfolio page that features their story.

- Ask the student to read the FAQ for Students.

- Please edit any work before your student submits an ePortfolio page.

Other levels in University Studies

- If I teach High School Senior Inquiry, Junior Clusters, or Senior Capstones, may I invite specific students with compelling stories to submit their work?

-

- Yes!

- Share the eReader’s FAQ for Students.

- Ask the students if they want to participate in this project, which is not related to their courses or grades.

- Edit the students’ stories for grammar and syntax for publication before they submit the work to us.

- If you already graded the student’s story, edit the work again for syntax.

- Although Óscar and David will edit submissions once more, we want faculty to be the first “writing coaches.”

Being a co-editor & are eReaders peer-reviewed publications?

- Are you (Óscar and David) looking for additional faculty to be co-editors?

-

- Yes!

- Reach out to us so we can gauge our simpatico and your bandwidth.

- As you may imagine, editing and writing takes time.

- We would love your help in editing student work!

- If I am a co-editor, does this eReader count as a peer-reviewed publication?

-

- Probably not.

- Óscar strongly suspects that an open-resource eReader at PSU does not count as a peer-reviewed publication.

- In his CV, Óscar places this eReader as “Other Scholarly Accomplishments.”

- Contact your chair and your promotion (or tenure) committee for additional answers.

References

Aguilar Becerra, Y., Diojuan, C., Walker, J., Malhotra, N., Peterson del Mar, D., & Reitenauer, L. (2022). “Who we are.” Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 53(5), 7-12.

Anti-Defamation League. (2020, June 18). What is DACA and who are the DREAMers? https://www.adl.org/education/resources/tools-and-strategies/table-talk/what-is-daca-and-who-are-the-dreamers

Baxter Magolda, M. & King, P. (2004). Self-authorship at the common goal of the 21st-century education. In M. Baxter-Magolda & P. King (Eds.), Learning partnerships: Theory and models of practice to educate for self-authorship (pp. 1-36). Stylus.

Beah, I. (2008). Long way gone: Memoirs of a boy soldier. Sarah Crichton.

Clance, P.R. & Imes, S.A. (1978). The impostor phenomenon in high achieving women: Dynamics and therapeutic intervention. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, and Practice, 15, 241–247.

Colorado State University. (2024, April 15). El Centro. https://elcentro.colostate.edu/about/why-latinx

Darling-Hammond, Kia. (2019). Queeruptions and the question of QTPOC thriving in schools: An excavation. Equity & Excellence in Education, 52(4), 424-434. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2019.1705205

Felder, R. M. (2016). Teaching and learning STEM : a practical guide. Jossey-Bass.

Fernández, Ó., Lundell, D., & Kerrigan, S. (2019). Taking high-impact practices to scale in capstone and peer mentor programs, and revising University Studies’ diversity learning goal. The Journal of General Education, 67(3–4), 269–289.

Fernández, Ó., Martin, S. B., Anaya, L. M., Diaz-Espinosa, A., Soriano-Valencia, W., Cadiz, S., Kinner, H., & Romero, D. (2022). Disrupting trauma tourism in diversity workshops and scholarship essays: A participatory study describing counternarratives by Queer, Trans, and Students of Colour.* In Martin, S. B., & Dandekar, D. (Eds.), Global south scholars in the western academy: Harnessing unique experiences, knowledges, and positionality in the third space (pp. 120-139). Routledge. *We followed UK spelling conventions for students “of colour.”

Fernández, Ó., Lawrence, A. F., Pirie, M. S., & Ring, G. (2023). Leveraging a campus equity walkthrough evaluation (CEWE) ePortfolio to assess first-year students’ equity-minded learning and campus belonging. International Journal of ePortfolio, 13(1), 21-54. https://www.aacu.org/ijep/archives/volume-13-number-1

Freire, P. (1987). Literacy: Reading the word & the world. Bergin & Garvey Publishers.

Garcia, S. E. (2020, June 17). Where did BIPOC come from? The acronym, which stands for Black, Indigenous and People of Color, is suddenly everywhere. Is it doing its job? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/article/what-is-bipoc.html

Hamington, M., & Ramaley, J. (2019). University Studies leadership: Vision and challenge. The Journal of General Education, 67(3–4), 290-309.

Noe-Bustamante, L., Mora, L. & Lopez, M. H. (2020, August 11). About one-in-four U.S. Hispanics have heard of Latinx, but just 3% use it. Pew Research Center: Hispanic Trends. https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2020/08/11/about-one-in-four-u-s-hispanics-have-heard-of-latinx-but-just-3-use-it

Langford, J., Clance, P. R. (Fall 1993). The impostor phenomenon: recent research findings regarding dynamics, personality and family patterns and their implications for treatment. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 30(3): 495–501. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.30.3.495

Lee, J. (2023). Biting the hand: Growing up Asian in Black and White America. Henry Holt.

Martin, S. B., Tavares, D., Philipos, M., Alvarez, A., Maranghi, I., Sanchez Cisneros, I. Diaz, D., & Peterson del Mar., D. (2022). Transforming ordinary spaces into hopeful spaces. In B. Martin 7 D. Dandekar (Eds.), Global south scholars in the western academy: Harnessing unique experiences, knowledges, and positionality in the third space (pp. 155-170). Routledge.

Noe-Bustamane, L., Mora, L. & Lopez, M. H. (2020, August 11). About one-in-four U.S. Hispanics have heard of Latinx, but just 3% use it. Pew Research Center: Hispanic Trends. https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2020/08/11/about-one-in-four-u-s-hispanics-have-heard-of-latinx-but-just-3-use-it

Peterson del Mar, D., Alharroubi, R., Borodkina, A., Davila Samayoa, K., Maldonado Ortega, D., Marquez Marquez, J., Organna, L., Reyes Moreno, E., Tran, H., Tuy, B, & Vo, T. (2022). Like a family: Fostering a sense of belonging in a minority-majority classroom. The Journal of Transformative Learning, 9(1), 121-124. https://jotl.uco.edu/index.php/jotl/article/view/446/370

Peterson del Mar, D. (2023, March 6). Transformations: Stories of hope and service. http://davidpetersondelmar.blogspot.com

Salazar, Ruben. (1970, February 6). Who is a Chicano? And what is it that Chicanos want? Los Angeles Times. https://library.ucsd.edu/dc/object/bb4096888h/_1.pdf

Stevens, D. D., & Cooper, J. E. (2009). Journal keeping: How to use reflective writing for learning, teaching, professional insight and positive change. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publications.

Stinckens, N., Lietaer, G., & Leijssen, M. (2002, March 1). The inner critic on the move: Analysis of the change process in a case of short-term client-centred/experiential therapy. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/14733140212331384978

Students from Immigration, Migration, and Belonging at Portland State University, 2021-2002, Noor, B., Monestime, O., Hines, J., & Peterson del Mar, D. (2023). A student bill of rights. Amplify: A Journal of Writing-As-Activism, 2(1), Article 5. https://doi.org/10.15760/amplify.2023.2.1.5

Students of color aren’t broken; systems, practices & policies are. (2020, August 6). EdTrust. https://edtrust.org/press-room/students-of-color-arent-broken-systems-practices-policies-are

University Studies. (n.d.). About University Studies. https://www.pdx.edu/university-studies/about-unst

University Studies. (n.d.). Freshman Inquiry. https://www.pdx.edu/university-studies/freshman-inquiry

University Studies. (n.d.). Senior Year Capstone. https://www.pdx.edu/university-studies/senior-year-capstone

University Studies. (n.d.). Sophomore Inquiry. https://www.pdx.edu/university-studies/sinq-junior-clusters

Vogt, E. E., Brown, J., & Issacs, D. (2003). The art of powerful questions: Catalyzing insight, innovation, and action. Whole Systems Associates.

Yosso, T. J. (2005). Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race, Ethnicity and Education, 8(1), 69-91.

Yosso, T. J. (2017). Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Critical Race Theory in Education (1st ed., pp. 113–136). Routledge. (Original work published in 2005.)

Zimmerman, J. (2020). The amateur hour: A history of college teaching in America. Johns Hopkins University Press.